Paracentesis

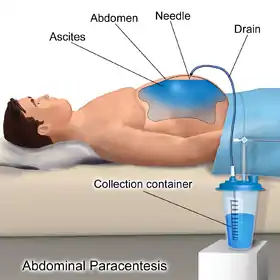

Paracentesis (from Greek κεντάω, "to pierce") is a form of body fluid sampling procedure, generally referring to peritoneocentesis (also called laparocentesis or abdominal paracentesis) in which the peritoneal cavity is punctured by a needle to sample peritoneal fluid.[1][2]

| Paracentesis | |

|---|---|

| |

| ICD-10-PCS | Illustration depicting Paracentesis |

| ICD-9-CM | 54.91 |

| MeSH | D019152 |

The procedure is used to remove fluid from the peritoneal cavity, particularly if this cannot be achieved with medication. The most common indication is ascites that has developed in people with cirrhosis.

Indications

It is used for a number of reasons:

- to relieve abdominal pressure from ascites

- to diagnose spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and other infections (e.g. abdominal TB)

- to diagnose metastatic cancer

- to diagnose blood in peritoneal space in trauma

For ascites

The procedure is often performed in a doctor's office or an outpatient clinic. In an expert's hands, it is usually very safe, although there is a small risk of infection, excessive bleeding or perforating a loop of bowel. These last two risks can be minimized greatly with the use of ultrasound guidance.

The patient is requested to urinate before the procedure; alternately, a Foley catheter is used to empty the bladder. The patient is positioned in the bed with the head elevated at 45–60 degrees to allow fluid to accumulate in lower abdomen. After cleaning the side of the abdomen with an antiseptic solution, the physician numbs a small area of skin and inserts a large-bore needle with a plastic sheath 2 to 5 cm (1 to 2 in) in length to reach the peritoneal (ascitic) fluid. The needle is removed, leaving the plastic sheath to allow drainage of the fluid. The fluid is drained by gravity, a syringe or by connection to a vacuum bottle. Several litres of fluid may be drained during the procedure; however, if more than two litres are to be drained, it will usually be done over the course of several treatments. After the desired level of drainage is complete, the plastic sheath is removed and the puncture site bandaged. The plastic sheath can be left in place with a flow control valve and protective dressing if further treatments are expected to be necessary.

If fluid drainage in cirrhotic ascites is more than 5 litres, patients may receive intravenous serum albumin (25% albumin, 8g/L) to prevent hypotension (low blood pressure).[3] There has been debate as to whether albumin administration confers benefit, but a recent 2016 meta-analysis concluded that it can reduce mortality after large-volume paracentesis significantly.[4] However, for every end-point investigated, while albumin was favorable as compared to other agents (e.g., plasma expanders, vasoconstrictors), these were not statistically significant and the meta-analysis was limited by the quality of the studies — two of which that were in fact unsuitable — included in it.[4]

The procedure generally is not painful and does not require sedation. The patient is usually discharged within several hours following post-procedure observation provided that blood pressure is otherwise normal and the patient experiences no dizziness.[1][5][6]

Fluid analysis

The serum-ascites albumin gradient can help determine the cause of the ascites.[3]

The ascitic white blood cell count can help determine if the ascites is infected. A count of 250 neutrophils per ml or higher is considered diagnostic for spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Cultures of the fluid can be taken, but the yield is approximately 40% (72-90% if blood culture bottles are used).[3]

Contraindications

Mild hematologic abnormalities do not increase the risk of bleeding.[7][3] The risk of bleeding may be increased if:[8]

- prothrombin time > 21 seconds

- international normalized ratio > 1.6

- platelet count < 50,000 per cubic millimeter.

Absolute contraindication is acute abdomen that requires surgery.

Relative contraindications are:

- Pregnancy

- Distended urinary bladder

- Abdominal wall cellulitis

- Distended bowel

- Intra-abdominal adhesions.[1]

References

- Paracentesis at eMedicine

- Farlex dictionary > paracentesis, citing:

- Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Copyright 2008

- The American Heritage Medical Dictionary Copyright 2007

- McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine. Copyright 2002

- Moore, K P; Aithal, G. P. (2006). "Guidelines on the management of ascites in cirrhosis". Gut. 55: vi1–12. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.099580. PMC 1860002. PMID 16966752.

- Bernardi, Mauro; Caraceni, Paolo; Navickis, Roberta J. (28 December 2016). "Does the evidence support a survival benefit of albumin infusion in patients with cirrhosis undergoing large-volume paracentesis?". Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 11 (3): 191–192. doi:10.1080/17474124.2017.1275961. PMID 28004601.

- "Treatments and Services | Gastroenterology and Hepatology | Dartmouth-Hitchcock".

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-12-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- McVay, PA; Toy, PT (1991). "Lack of increased bleeding after paracentesis and thoracentesis in patients with mild coagulation abnormalities". Transfusion. 31 (2): 164–71. doi:10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31291142949.x. PMID 1996485.

- Ginès, Pere; Cárdenas, Andrés; Arroyo, Vicente; Rodés, Juan (2004). "Management of Cirrhosis and Ascites". New England Journal of Medicine. 350 (16): 1646–54. doi:10.1056/NEJMra035021. PMID 15084697.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paracentesis. |

- Paracentesis - a step-by-step procedure guide. Clinical Notes.

- WebMD: Patient guide