Castle of Mertola

The Castle of Mértola (Portuguese: Castelo de Mértola) is a well-preserved medieval castle located in the civil parish and municipality of Mértola, in the Portuguese district of Beja.

| Castle of Mértola | |

|---|---|

Castelo de Mértola | |

| Beja, Baixo Alentejo, Alentejo in Portugal | |

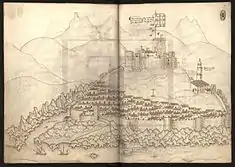

A view of the castle as situated on the hilltop, with the mosque/Christian church | |

| Coordinates | 37°38′20.4″N 7°39′49.5″W |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | Portuguese Republic |

| Operator | Câmara Municipal de Mértola, ceded on 18 January 1941 (adjacent terrains) |

| Open to the public | Public |

| Site history | |

| Built | 318 B.C. |

| Materials | Stone masonryAlvenaria, Tile, Cornerstone, Taipa |

History

In 318 B.C., during the sequence of the invasion and sack of Tyre, by Alexander the Great, the Phoenicians founded the Myrtilis or New Tyre.[1][2] The region became an important trading center frequented by Phoenicians and Carthaginians, thanks to the abundance of river and land routes connecting it to the southern portion of the peninsula. Before the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula, it held commercial importance among these civilizations.

During the Roman epoch, the settlement was developed, becoming the centre of the mineral extract and agriculture in the Baixo Alentejo region. Mértola was encircled by a wall system that paralleled what remains today, but much grander.[2] The Beja road crossed the walls in the north,[3] and by 44 B.C. Julius Caesar had renamed the town Myrtilis Julia.[2] The first historical reference to this settlement existed in the chronicles of the Swabian bishop, Idácio, who narrated an episode dating to 440 AD, and inferred the existence of this fortified site occupied by Swabians and Visigoths.

It was destroyed and sacked by barbarian hordes, then Muslim Umayyad , who reconstructed the centre for their own necessities, where the name Myrtilis was shortened to Martula.[2] Ibn Qasi was governor of the Taifa of Mértola it is likely that defensive works during his rule (1144-1151) were carried out to the castle.

In the middle of the 12th century, the ribat was constructed on the south tower of the dungeon.[2][4] During the last third of the 12th century, during the Almohad dynasty, the site was repaired and the walls were constructed to encircle the settlement.[2] During that time, the group of castle buildings were constructed, or reconstructed, that includes the semi-cylindrical tower. In 1171, Abu Háfece, brother of the Emir, ordered the repair and improvements to the fortress tower.[2][5]

In 1238, during the context of the Reconquista, Mértola was conquered by Sancho II, putting an end to centuries of Islamic reign.[2]

Between 1240/1245 and 1316, the settlement became the seat of the Military Order of Santiago. In 1254, D. Paio Peres Correia issued the regions first foral (charter).[2] The master of the Order, João Fernandes (from the inscription over the entranceway) that ordered the construction of the keep tower in 1292.[2]

In the final decade of the 13th century, or beginning of the 14th century, the dungeons were reconstructed, taking advantage of the older gate and tower of Carocha.[2] This work was supplemented in 1373, by improvements to the dungeons and walls.[2]

Following the signing of the Treaty of Monçao in 1386, the military territories of Mértola, Noudar, Castelo Mendo and Castelo Melhor returned to the possessions of the Portuguese Crown, in exchange for Olivença and Tui.[2] This resulted in further improvements in 1404 to the fortifications.[2]

In the final of the 15th century, the alcalde's residence was constructed, addorsed to the Keep Tower, resulting in much of the demolition of the northwestern battlements.[2] Yet, work persisted in improving the dungeons and walls, although in a diminished capacity.[2] On 25 February 1510, Nuno Velho authored to the King on the state of the fortifications.[2] In 1512, King D. Manuel issued a regal foral.,[2] and the castle was recorded by Duarte de Armas (Book of Fortresses in 1509) On 15 October 1513, there is record of a royal letter to pay Francisco de Anzinho 94,260 reis for furnishing lime for the work on the castle.[2]

Until the 18th century, the castle of Mértola continued to function as part of the first defensive line along the frontier with Spain, but began to diminish its military-strategic importance over time, before it was ultimately abandoned.[2] Although important in southern Portugal, the village and castle lost most of its importance during the era of Portuguese maritime expeditions and colonization. Most of the sites decline was reflected in general neglect and lack of conservation, so much that by 1758, the location was in semi-ruin and un-garrisoned.

Between the 19th and 20th century, Mértola's economy was dependent on the exploitation of the mines of Santo Domingo, a major center for cupric pyrite extraction.

On 18 August 1943, by decree 32/973 (Diário do Governo, Série 1, 175), the heritage site was classified as a Imóvel de Interesse Público (Property of Public Interest). On 2 February 1969, an earthquake caused damage to the old fortress.[2]

On 1 June 1992, the property fell into the administration of the Instituto Português do Património Arquitetónico (Portuguese Institute for Architectural Patrimony), under decree-law 106F/92 (Diário da República, Série 1A, 126).[2] A revitalization project began in the 20th century saw the site transformed into a village museum with different areas specializing in different areas related to the castle's history: the keep tower was transformed into an observation deck as well as an interpretative centre presenting Roman, Visigothic Nucleus, Christian and Islamic collections that include one of the best collections Portuguese Islamic art (such as pottery, coins, and jewelry).

Architecture

The Castle of Mértola is situated in an urban area on the hilltop, implanted in the rocky landscape bisected by the Guadiana River and the Ribeira de Oeiras.[2] Situated nearby is the former Islamic mosque, transformed into the Church of Nossa Senhora da Assunção.[2]

The irregular, rectangular fortress includes four towers: the rectangular keep tower at an angle oriented to the north, two square towers to the south; two rectangular towers to the south; two towers aligned to the principal gate in the east; and a rectangular tower, with circular affect.[2] The "traitors gate" is situated in the northwest wall of the fortifications, following the Keep Tower, protected by barbican.[2] The wall is part of a circuit of battlements, vertical and reinforced by a southwestern tower with large buttress supporting various battlements.[2]

The Keep Tower is 30 metres (98 ft) tall, with soft base and two floors, marked by doorway that opens to staircase addorsed to the southeast walls, consisting of varias friezes along the northwest and marked by machialottans, surmounted by parapets and prismatic merlons and decorated in pyramids. The weapons hall is situated on the first floor, covered with cross-vaulted ceiling.[2] A staircase along the southern wall provides access to the second floor. Alongside the keep tower is a sculpted white marble, relief coat-of-arms of António Rodrigues Bravo, High-Courier (postal official) of the town.[2]

The Carouche Tower, in the southwest, is a cubic 4.7 metres (15 ft) wide, with access from the battlements and covered by terrace, broken by door and window. Its interior, is a covered space with hemispheric cupola over pedestals.[2] The towers in the corners flank the main gate, with different volumes (the left is prismatic and the right, semi-circular), that do not extend beyond the height of the battlements.[2]

In the courtyard is a covered cistern with vaulted ceiling over three arches.[2]

The walls encircling the settlement can still be identifiable, defined as a sub rectangular space along the north-to-south axis, with reinforced walls by rectangular towers: a large segment along the north, while a majority of the walls extend along the south flowing from the Carocha Tower, with a part oriented along the Guadiana.[2] To ancient gates, survived by the Misericórdia Gate provides access to the river.[2]

References

Notes

- Almeida (1943/1949)

- Mendonça, Isabel; Gordalina, Rosário (2007), SIPA (ed.), Castelo de Mértola/Castelo e cerca urbana de Mértola (IPA.00001045/PT040209040003) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal: SIPA – Sistema de Informação para o Património Arquitectónico, retrieved 25 August 2016

- Torres (1990)

- Gonçalves (1981)

- Torres (1991)

Sources

- Almeida, João de (1943), O Livro das Fortalezas de Duarte Darmas (edição anotada) (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Roteiro dos Monumentos Militares Portugueses (in Portuguese), III, Lisbon, Portugal, 1948

- Ministério das Obras Públicas, ed. (1956), Relatório da Actividade do Ministério no ano de 1955 (in Portuguese), Lisbon, Portugal

- Gonçalves, José Pires (1981), As Arrábidas de Mértola e Juromenha (in Portuguese), 27 (Série 2 ed.), Lisbon, Portugal: Anais da Academia Portuguesa de História

- Torres, Cláudio; Silva, Luís Alves da (1990), Mértola: vila museu (in Portuguese), Mértola, Portugal

- Torres, Cláudioe (1991), Museu de Mértola I: Núcleo do Castelo (Catálogo) (in Portuguese), Mértola, Portugal

- Barros, Maria de Fátima Rombouts; Boiça, Joaquim Manuel Ferreira (1 April 2000), "O Castelo de Mértola: estrutura e organização espacial (Sécs. XIII a XVI )", Actas Simpósio Internacional sobre Castelos (in Portuguese), Palmela, Portugal