Charles Le Myre de Vilers

Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (17 February 1833 – 9 March 1918) was French naval officer, then departmental administrator. He was governor of the colony of Cochinchina (1879–1882) and resident-general of Madagascar (1886–1888). He was a member of the French National Assembly from 1889 to 1902, representing Cochinchina.

Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers | |

|---|---|

| |

| Governor of Cochinchina | |

| In office 7 July 1879 – 7 November 1882 | |

| Preceded by | Louis Charles Georges Jules Lafont |

| Succeeded by | Arthur de Trentinian (acting) Charles Antoine François Thomson |

| Resident-general of Madagascar | |

| In office 1886–1888 | |

| Deputy of Cochinchina | |

| In office 12 December 1889 – 31 May 1902 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 February 1833 Vendôme, Loir-et-Cher, France |

| Died | 9 March 1918 (aged 85) Paris, France |

| Nationality | French |

Life

Early years (1833–61)

Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers was born in Vendôme, Loir-et-Cher, on 17 February 1833.[1] His parents were Cyprien Le Myre de Vilers, a colonel in the Cavalry, and Claire Hême (1808–1848).[2] Charles decided on a career in the navy, entered the Naval School in 1849, was a midshipman in 1853 and a Lieutenant in 1855. He was made a Knight of the Legion of Honour on 13 August 1859.[3]

Departmental administration (1861–79)

Le Myre de Vilers left the navy in 1861 and joined the prefectural administration.[3] On 22 April 1862 he married Isabelle Hennet (born 1841) in Paris. Their children included Hélène, Jean (1866–1934) and Madeleine (1870–1894).[2] Le Myre de Vilers was appointed sub-prefect of Joigny on 1 March 1863, then sub-prefect of Bergerac on 30 October 1867. He was appointed Prefect of Algiers in November 1869.[3]

During the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 Le Myre de Vilers rejoined the navy and served as lieutenant de vaisseau. He was orderly officer to Admiral de La Roncière(fr), commanding the seamen's corps during the Siege of Paris. For his conduct during the siege he was awarded the rosette of the Legion of Honour on 26 January 1871. He left the navy a month later and rejoined the prefectural administration. On 26 March 1873 he was appointed Prefect of Haute-Vienne. He was director of civil and financial affairs in Algeria from 1877 to 1879, appointed at the request of General Antoine Chanzy.[3]

Cochinchina and Cambodia

On 11 August 1863 Admiral Pierre-Paul de La Grandière signed a Treaty of Friendship, Trade and French Protection with King Norodom of Cambodia.[4] The French privatized land ownership, collected taxes and put down a rebellion in 1867.[5] A dispute over the power of King Norodom of Cambodia begin in 1874 when a stream of crates addressed to the king began to arrive in Saigon, sent from France by the businessman Thomas Caraman. The last crates arrived in 1876 and contained a wonderful gilded screen for the royal throne chamber, but nobody from the palace came to claim the crates. A trial began in October 1874 with Caraman trying to collect payment from the King.[6] The French state attorney and the Cambodian grand mandarin both refused to hear the case, since the idea that a king should be tried in court was unprecedented. In 1877 Caraman returned to France to drum up support, and in March 1878 six senators wrote a letter to the Minister of the Marine and Colonies asking him to ensure Caraman received justice. The Minister instructed Governor Louis Charles Georges Jules Lafont to resolve the affair.[7]

Le Myre de Vilers was appointed the first civilian governor of Cochinchina on 13 May 1879, and Minister Plenipotentiary at the Court of Annam.[8] He inherited the dispute between Caraman and Norodon.[7] He tried his best to resolve the problem. One idea, later abandoned, was to raffle off the gilded screen. Le Myre de Vilers sent the politician Jules Blancsubé to negotiate with Norodom in Phnom Penh, but he did not succeed. Eventually the king agreed to buy the screen for 25,000 piasters, half of Caraman's price, as a gesture of friendship to the governor, and on 21 February 1881 22 chests containing the screen were shipped off to Phnom Penh. In December 1881 Le Myre de Vilers forced Norodom to accept a convention under which Saigon's Conseil Privé could rule over disputes like this.[7] He wrote,

I believe that we render a real service to His Majesty if we give him the means to settle contentious litigations resulting from contracts made with Europeans. We thus shield His Majesty from ventures of schemers who will always end up abusing the Royal treasury; [and] we ensure for Cambodia the financial cooperation of respectable firms."[9]

Le Myre de Vilers tried to define a clear distinction between civil and military responsibilities, to draft a penal code, to create district councils, a Saigon city council and a Council of the colony of Conchinchina. He also began construction of a road and rail network. He was hostile to the Tonkin Campaign, which caused his dismissal in May 1882. He retired in 1883.[3] In June 1884 his successor Charles Thomson forced Norodom to sign a new agreement and started to consider outright annexation of Cambodia.[8]

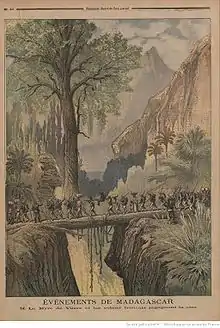

Madagascar

Le Myre de Vilers was recalled to the service on 9 March 1886 by Charles de Freycinet, who appointed him Plenipotentiary Minister 1st Class and Resident General in Madagascar, a position newly created by the Franco-Malagasy treaty of 17 December 1885. He arrived in Antananarivo on 14 May 1886.[3] His task was to ensure the application of the 17 December 1885 Franco-Malagasy treaty, whose interpretation was disputed. Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony relied on the Patrimonio-Miot interpretive letter, which Le Myre de Vilers rejected. He managed to get the Malagasy government to take out a loan from the Comptoir national d'escompte de Paris in order to pay the 10 million francs compensation agreed in the treaty. He could not get agreement on the boundaries of the territory of Diego-Suarez, which the French troops eventually defined unilaterally.[10]

Le Myre de Vilers was active in construction of the Antananarivo-Toamasina telegraph line, completed in 1888. He maintained good relations with the court of Antananarivo, and had great respect for Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony. He wrote on 10 June 1886 to the Minister of Foreign Affairs that, "My task is laborious because I have to deal with a man of real value, a man with extreme skill who, on a larger stage, would be considered a genius". Le Myre de Vilers took leave in France from March to November 1888. On his return he presented Queen Ranavalona III with the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour.[10] In December 1888 he was himself made a Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour.[3]

Deputy (1889–1902)

Le Myre de Vilers left his post in Madagascar in July 1889 to run for Deputy of Cochinchina.[3] He was elected to the Chamber of Deputies as representative of French Cochinchina on 12 December 1889 and was reelected on 20 August 1893 and on 8 May 1898, holding office until 31 May 1902.[11] Le Myre de Vilers was a member of the committees on the navy and the colonies. He wrote many reports on aspects such as budgets, organization and development of colonies. In 1890 he supported creation of an Colonial Office independent of the navy.[3]

Dispute with Siam

The French claimed authority to all land east of the Mekong, and in April 1893 sent French and Annamite troops into Laos to evict Siamese officials and troops from that region. They met resistance. Phra Yot, the Siamese Commissioner of Khammouane, had the French Inspector Grosgurin and his escort massacred.[12] On 20 July 1893 the French parliament issued an ultimatum to Siam (Thailand) demanding that Bangkok relinquish all claims to the east bank of the Mekong, pay indemnity to the victims of Siamese aggression and punish the officers responsible for attacks on French troops. The deputies also agreed that Jules Develle, the Foreign Minister, should send Le Myre de Vilers to Bangkok to negotiate a treaty to guarantee French rights along the Mekong and to obtain compensation from Siam.[13] The Siamese responded by agreeing to withdraw their troops, pay the indemnity and punish any individuals who had acted unlawfully, but asked for international arbitration over the territorial claims and a joint commission to investigate the French claims for indemnity. Develle considered this response "insolent" and "unsatisfactory", imposed a blockade on 26 July 1893 and issued a second ultimatum, which the Siamese accepted rather than lose yet more territory.[14]

Le Myre de Vilers arrived in Bangkok on 16 August 1893. He openly intended to impose "very harsh" measures on the Siamese and thought it a waste of time to negotiate with them. At his second meeting with Prince Devawongse Varoprakar, who represented Siam, he asked the prince to sign a copy of the proposed Treaty of Peace and Friendship. The prince politely refused, since he had not examined the document. Le Myre de Vilers then told him the French warships in the Gulf of Siam could at any moment make matters quickly change for the worse.[15] Le Myre de Vilers demanded that Phra Yot be tried before a Franco-Siamese Mixed Court dominated by the French, while the Siamese offered a trial by a court of "competent Siamese authorities in conjunction with the [French] consul."[15]

On 29 September 1893 Le Myre de Vilers handed a draft Treaty and draft Convention to Devewongse and said he would leave for Saigon in four days with or without an agreement. When examined, the convention was found to include a proposal that Phra Yot be tried by a Mised Franco-Siamese Court, which the Siamese found completely unacceptable. At a final meeting on 1 October 1893 Le Myre de Vilers refused to alter the Convention but agreed to append a procès-verbal to address Siamese concerns. The exhausted Prince finally gave in and signed the Treaty and Convention to avoid the risk of war against superior French forces.[16]

Return to Madagascar

After Le Myre de Vilers left Madagascar the situation deteriorated.[3] In late June 1894 the French resident general, Paul Augustin Jean Larrouy, said the state of affairs in Tananarive was very tense. On 9 September 1894 French Foreign Minister Gabriel Hanotaux ordered Larrouy to return to France "on vacation" and ordered women and children to be evacuated to a coastal point where three gunboats would be waiting. On 12 September Hanotaux spoke in the Chamber of Deputies about the many ways in which the French were being harassed in Madagascar. The government was sending Le Myre de Vilers as its plenipoteniary.[17] He would take a treaty that covered the four main grievances, all of which must be accepted or France would seek a non-negotiated settlement.[18]

Le Myre de Vilers returned to Tananarive on 14 October 1894.[3] He requested an audience with the prime minister as soon as he arrived in the capital. When Rainilaiarivony delayed the meeting, Le Myre de Vilers sent a copy of the treaty with a deadline of five days to accept it. The two men met on 21 October 1884. Le Myre de Vilers warned the prime minister, "Let your Excellency be under no illusion. The result of any war can be foreseen: it will be a shattering defeat of the Malagasy people." He said the French government was not satisfied with the Malagasy justice system, which had corrupt officials and made little effort to apprehend criminals, and was considering taking control over internal affairs. The Malagasy government replied on 24 October 1884, saying the French could handle external relations but other rights under the 1885 treaty were abrogated. Le Myre de Vilers wrote a personal letter to Rainilairivony in which he advised him to fully accept the French demands. When it became clear that there would be no reply the remaining French residents prepared to leave for the coast.[19]

Le Myre and the other members of the French mission reached Tamatave on 4 November 1884. In his last dispatch to Hanotaux he acknowledged that the prime minister would have lost the support of his people if he compromised with the French. "Of two perils, the prime minister has chosen the more distant, a rupture with France, hoping to profit from a European incident which might turn our attention from Madagascan affairs. He recommended that a military expedition be launched in the next dry season.[20] That winter French troops under General Metzinger(fr) occupied the ports of Tamatave and Majunga, and in March 1885 most of the 15,000-strong expeditionary force disembarked unopposed. The French troops suffered badly from poor sanitation and tropical disease, and it was not until early 1897 that the island had been secured.[21]

Last years

After his return to France Le Myre de Vilers intervened in discussions in the Chamber on the annexation of Madagascar, abolition of slavery there, and the actions of Joseph Gallieni, which he fully supported. Le Myre de Vilers chose not to run for reelection in 1902. In his retirement he devoted himself to geography. He had been a member of the central committee of the Geographical Society since 1896, and was president of the society from 1906 to 1908. He belonged to various other societies related to the colonies.[3] Le Myre de Vilers died on 9 March 1918 in Paris.[11]

Publications

Publications by Le Myre de Vilers include, among many others:[1]

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1877), Notes sur la situation financière du département de la Haute-Vienne, Limoges: impr. de Chapoulard frères, p. 13

- Boilloux; François Eugène Oscar Gally Passebosc; J. Geisendörfer; Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1881), Cochinchine française. Plan topographique de l'arrondissement de Gocong, Impr. de Lemercier, p. 1

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (15 March 1888), Organisation administrative de l'Indochine française. Projet de rapport au président de la République, Preface by Noël Pardon, p. 22

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (14 June 1890), Rapport fait au nom de la Commission du budget chargée d'examiner le projet de loi portant fixation du budget général de l'exercice 1891 (Ministère du Commerce, de l'industrie et des colonies. Service des colonies) (Chambre des Députés, 5e législature, session 1890, n ° 665), Paris: Motteroz / France. Chambre des députés, p. 96

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (2 May 1891), Rapport fait au nom de la commission de la marine, chargée d'examiner le projet de loi portant organisation du cadre des officiers de la marine et des équipages de la flotte (Chambre des Députés, 5e législature, session 1891, n ° 1401), Paris: Motteroz / France. Chambre des députés, p. 105

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (7 November 1891), Rapport fait au nom de la commission de la marine chargée d'examiner le projet de loi portant organisation du corps des officiers mécaniciens de la marine (Chambre des Députés, 5e législature, session extraordinaire 1891, n ° 1705), Paris: Motteroz / France. Chambre des députés, p. 88

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (14 November 1891), Rapport fait au nom de la commission du budget chargée d'examiner le projet de loi portant fixation du Budget général de l'exercice 1891 (Ministère du Commerce, de l'industrie et des colonies. Service des colonies. Subvention de la métropole au budget de l'Annam et du Tonkin. Contingent de la Cochinchine) (Chambre des Députés, 5e législature, session extraordinaire 1890, n ° 994), Paris: Motteroz / France. Chambre des députés, p. 154

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (10 July 1900), Rapport... (budget général de 1901 : ministère des colonies) (Chambre des députés. 7e législature. Session 1900. N ° 1856), Paris: Impr. de Motteroz / France. Chambre des députés, p. 287

- Ernest Fallot; Jean-Léon Gérôme; Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers; André Liesse; Camille Paris (1904), Préparation aux carrières coloniales: conférences, Preface by Joseph Chailley-Bert, Paris: A. Challamel / Union coloniale française, p. 468

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1908), Les institutions civiles de la Cochinchine (1879–1881) : recueil des principaux documents officiels, Paris: E. Paul, p. 198

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (c. 1910), Les Affaires du Tonkin, 1873–1883

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1913), La politique coloniale française depuis 1830 (Association professionnelle des écrivains militaires, maritimes et coloniaux), Paris: La Nouvelle revue, p. 30

References

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1833–1918) – BnF.

- Pierfit.

- Jolly 1960.

- Corfield 2009, p. 23.

- Corfield 2009, pp. 24–25.

- Muller 2006, p. 123.

- Muller 2006, p. 124.

- Corfield 2009, p. 27.

- Muller 2006, p. 125.

- Pela Ravalitera 2012.

- Charles Le Myre de Vilers – Assemblée.

- Heller & Simpson 2013, p. 52.

- Heller & Simpson 2013, p. 53.

- Heller & Simpson 2013, p. 54.

- Heller & Simpson 2013, p. 55.

- Heller & Simpson 2013, p. 56.

- Iiams 1962, p. 30.

- Iiams 1962, pp. 30–31.

- Iiams 1962, p. 31.

- Iiams 1962, p. 32.

- Iiams 1962, pp. 33ff.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Charles Le Myre de Vilers. |

Sources

- Charles Le Myre de Vilers, Assemblée nationale, retrieved 14 July 2018

- Charles-Marie Le Myre de Vilers (1833–1918) (in French), BnF: Bibliotheque nationale de France, retrieved 14 July 2018

- Corfield, Justin (13 October 2009), The History of Cambodia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-35723-7

- Heller, Kevin; Simpson, Gerry (2013), The Hidden Histories of War Crimes Trials, OUP Oxford, ISBN 978-0-19-967114-4

- Iiams, Thomas M. (1962), Dreyfus, Diplomatists and the dual Alliance. Gabriel Hanotaux at the Quai dOrsay (1894-1898), Librairie Droz, ISBN 978-2-600-04281-9

- Jolly, Jean, ed. (1960), "Le Myre de Vilers (Charles)", Dictionnaire des parlementaires français de 1889 à 1940, Presses universitaires de France, retrieved 14 July 2018

- Muller, Gregor (7 April 2006), Colonial Cambodia's 'Bad Frenchmen': The rise of French rule and the life of Thomas Caraman, 1840–87, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-25372-2

- Pela Ravalitera (13 February 2012), "Le Myre de Vilers, le négociateur français dans l'île", L'Express (Notes du passé) (in French), retrieved 14 July 2018

- Pierfit, "Charles Le MYRE de VILERS", Geneanet (in French), retrieved 14 July 2018