Christ myth theory

The Christ myth theory, also known as the Jesus myth theory, Jesus mythicism, or the Jesus ahistoricity theory,[1] is the view that the story of Jesus is largely fictitious, and has little basis in historical fact.[2] Alternatively, in terms given by Bart Ehrman paraphrasing Earl Doherty, "the historical Jesus did not exist. Or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity."[q 1] Most scholars of antiquity support the historicity of Jesus and reject the Christ myth theory as it is a fringe view [q 2].[3][4][5][6] One such criticism is its reliance on comparisons between mythologies.[7]

| Christ myth theory | |

|---|---|

The Resurrection of Christ by Carl Heinrich Bloch (1875)—some mythicists see this as a case of a dying-and-rising deity | |

| Description | The story of Jesus of Nazareth is entirely a myth. He never existed as a historical person, or if he did, he had virtually nothing to do with the founding of Christianity and the accounts in the gospels. |

| Early proponents |

|

| Later proponents |

|

| Living proponents | Robert M. Price, Richard Carrier |

| Subjects | Historical Jesus, Historical reliability of the Gospels, Historicity of Jesus |

| Part of a series on |

|

|

There are three strands of mythicism, including the view that there may have been a historical Jesus, who lived in a dimly remembered past, and was fused with the mythological Christ of Paul.[8][9][q 3] A second stance is that there was never a historical Jesus, only a mythological character, later historicized in the Gospels.[q 1] A third view is that no conclusion can be made about a historical Jesus, and if there was one, nothing can be known about him.[10]

Most Christ mythicists follow a threefold argument:[11] they question the reliability of the Pauline epistles and the Gospels to establish the historicity of Jesus; they note the lack of information on Jesus in non-Christian sources from the first and early second centuries; and they argue that early Christianity had syncretistic and mythological origins, as reflected in both the Pauline epistles and the gospels, with Jesus being a celestial being who was concretized in the Gospels. Therefore, Christianity was not founded on the shared memories of a man, but rather a shared mytheme.

Traditional and modern approaches on Jesus

The origins and rapid rise of Christianity, as well as the historical Jesus and the historicity of Jesus, are a matter of longstanding debate in theological and historical research. While Christianity may have started with an early nucleus of followers of Jesus,[12] within a few years after the presumed death of Jesus in c. AD 33, at the time Paul started preaching, a number of "Jesus-movements" seem to have been in existence, which propagated divergent interpretations of Jesus' teachings.[13][14] A central question is how these communities developed and what their original convictions were,[13][15] as a wide range of beliefs and ideas can be found in early Christianity, including adoptionism and docetism,[web 1] and also Gnostic traditions which used Christian imagery,[16][17] which were all deemed heretical by proto-orthodox Christianity.[18][19]

Quest for the historical Jesus

A first quest for the historical Jesus took place in the 19th century, when hundreds of Lives of Jesus were being written. David Strauss (1808–1874) pioneered the search for the "Historical Jesus" by rejecting all supernatural events as mythical elaborations. His 1835 work, Life of Jesus,[20] was one of the first and most influential systematic analyses of the life story of Jesus, aiming to base it on unbiased historical research.[21][22] The Religionsgeschichtliche Schule, starting in the 1890s, used the methodologies of higher criticism,[web 2] a branch of criticism that investigates the origins of ancient texts in order to understand "the world behind the text".[23] It compared Christianity to other religions, regarding it as one religion among others and rejecting its claims to absolute truth, and demonstrating that it shares characteristics with other religions.[web 2] It argued that Christianity was not simply the continuation of the Old Testament, but syncretistic, and was rooted in and influenced by Hellenistic Judaism (Philo) and Hellenistic religions like the mystery cults and Gnosticism.[web 3] Martin Kähler questioned the usefulness of the search for the historical Jesus, making the famous distinction between the "Jesus of history" and the "Christ of faith", arguing that faith is more important than exact historical knowledge.[24][25] Rudolf Bultmann (1884–1976), who was related to the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule,[web 3] emphasized theology, and in 1926 had argued that historical Jesus research was both futile and unnecessary; although Bultmann slightly modified that position in a later book.[26][27]

This first quest ended with Albert Schweitzer's 1906 critical review of the history of the search for Jesus's life in The Quest of the Historical Jesus – From Reimarus to Wrede. Already in the 19th and early 20th century, this quest was challenged by authors who denied the historicity of Jesus, notably Bauer and Drews.

The second quest started in 1953, in a departure from Bultmann.[26][27] Several criteria, the criterion of dissimilarity and the criterion of embarrassment, were introduced to analyze and evaluate New Testament narratives. This second quest faded away in the 1970s,[22][28] due to the diminishing influence of Bultmann,[22] and coinciding with the first publications of Wells, which marks the onset of the revival of Christ myth theories. According to Paul Zahl, while the second quest made significant contributions at the time, its results are now mostly forgotten, although not disproven.[29]

The third quest started in the 1980s, and introduced new criteria.[30][31] Primary among these are[31][32] the criterion of historical plausibility,[30] the criterion of rejection and execution,[30] and the criterion of congruence (also called cumulative circumstantial evidence), a special case of the older criterion of coherence.[33] The third quest is interdisciplinary and global,[34] carried out by scholars from multiple disciplines[34] and incorporating the results of archeological research.[35]

The third quest yielded new insights into Jesus' Palestinian and Jewish context, and not so much on the person of Jesus himself.[36][37][38] It also has made clear that all material on Jesus has been handed down by the emerging Church, raising questions about the criterion of dissimilarity, and the possibility of ascribing material solely to Jesus, and not to the emerging Church.[39]

A historical Jesus existed

These critical methods have led to a demythologization of Jesus. The mainstream scholarly view is that the Pauline epistles and the gospels describe the Christ of faith, presenting a religious narrative which replaced the historical Jesus who did live in 1st-century Roman Palestine.[40][41][42][43][note 1] Yet, that there was a historical Jesus is not in doubt. New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman states that Jesus "certainly existed, as virtually every competent scholar of antiquity, Christian or non-Christian, agrees".[45][46]

Following the criteria of authenticity-approach, scholars differ on the historicity of specific episodes described in the Biblical accounts of Jesus,[47] but the baptism and the crucifixion are two events in the life of Jesus which are subject to "almost universal assent".[note 2] According to historian Alanna Nobbs,

While historical and theological debates remain about the actions and significance of this figure, his fame as a teacher, and his crucifixion under the Roman prefect Pontius Pilate, may be described as historically certain.[48]

The portraits of Jesus have often differed from each other and from the image portrayed in the gospel accounts.[46][49][50][note 3] The primary portraits of Jesus resulting from the Third Quest are: apocalyptic prophet; charismatic healer; cynic philosopher; Jewish Messiah; and prophet of social change.[51][52] According to Ehrman, the most widely held view is that Jesus was an apocalyptic prophet,[53] who was subsequently deified.[54]

According to James Dunn, it is not possible "to construct (from the available data) a Jesus who will be the real Jesus".[55][56] According to Philip R. Davies, a Biblical minimalist, "what is being affirmed as the Jesus of history is a cipher, not a rounded personality".[web 5] According to Ehrman, "the real problem with Jesus" is not the mythicist stance that he is "a myth invented by Christians", but that he was "far too historical", that is, a first-century Palestine Jew, who was not like the Jesus preached and proclaimed today.[57] According to Ehrman, "Jesus was a first-century Jew, and when we try to make him into a twenty-first century American we distort everything he was and everything he stood for."[58]

Demise of authenticity and call for memory studies

Since the late 2000s, concerns have been growing about the usefulness of the criteria of authenticity.[59][60][61][web 6][web 7] According to Keith, the criteria are literary tools, indebted to form criticism, not historiographic tools.[62] They were meant to discern pre-Gospel traditions, not to identify historical facts,[62] but have "substituted the pre-literary tradition with that of the historical Jesus".[63] According to Le Donne, the usage of such criteria is a form of "positivist historiography".[64]

Chris Keith, Le Donne, and others[note 4] argue for a "social memory" approach, which states that memories are shaped by the needs of the present. Instead of searching for a historical Jesus, scholarship should investigate how the memories of Jesus were shaped, and how they were reshaped "with the aim of cohesion and the self-understanding (identity) of groups".[63]

James D. G. Dunn's 2003 study, Jesus Remembered, was the onset for this "increased ... interest in memory theory and eyewitness testimony".[web 8][web 9] Dunn argues that "[t]he only realistic objective for any 'quest of the historical Jesus' is Jesus remembered."[65] Dunn argues that Christianity started with the impact Jesus himself had on his followers, who passed on and shaped their memories of him in an oral gospel tradition. According to Dunn, to understand who Jesus was, and what his impact was, scholars have to look at "the broad picture, focusing on the characteristic motifs and emphases of the Jesus tradition, rather than making findings overly dependent on individual items of the tradition".[65]

Anthony le Donne elaborated on Dunn's thesis, basing "his historiography squarely on Dunn’s thesis that the historical Jesus is the memory of Jesus recalled by the earliest disciples".[web 8] According to Le Donne, memories are refactored, and not an exact recalling of the past.[web 8] Le Donne argues that the remembrance of events is facilitated by relating it to a common story or "type". The type shapes the way the memories are retained, c.q. narrated. This means that the Jesus-tradition is not a theological invention of the early Church, but is shaped and refracted by the restraints that the type puts on the narrated memories, due to the mold of the type.[web 8]

According to Chris Keith, an alternative to the search for a historical Jesus "posits a historical Jesus who is ultimately unattainable, but can be hypothesized on the basis of the interpretations of the early Christians, and as part of a larger process of accounting for how and why early Christians came to view Jesus in the ways that they did". According to Keith, "these two models are methodologically and epistemologically incompatible", calling into question the methods and aim of the first model.[66]

Christ myth theorists

Mythicists argue that the accounts of Jesus are to a large extent, or completely, of a mythical nature, questioning the mainstream paradigm of a historical Jesus in the beginning of the 1st century who was deified. Most mythicists, like mainstream scholarship, note that Christianity developed within Hellenistic Judaism, which was influenced by Hellenism. Early Christianity, and the accounts of Jesus are to be understood in this context. Yet, where contemporary New Testament scholarship has introduced several criteria to evaluate the historicity of New Testament passages and sayings, most Christ myth theorists have relied on comparisons of Christian mythemes with contemporary religious traditions, emphasizing the mythological nature of the Bible accounts.[67][note 5]

Some moderate authors, most notably Wells, have argued that there may have been a historical Jesus, but that this historical Jesus was fused with another Jesus-tradition, namely the mythological Christ of Paul.[8][9][q 3] Others, most notably the early Wells and Alvar Ellegård, have argued that Paul's Jesus may have lived far earlier, in a dimly remembered remote past.[69][70][71]

The most radical mythicists hold, in terms given by Price, the "Jesus atheism" viewpoint, that is, there never was a historical Jesus, only a mythological character, and the mytheme of his incarnation, death, and exaltation. This character developed out of a syncretistic fusion of Jewish, Hellenistic and Middle Eastern religious thought; was put forward by Paul; and historicised in the Gospels, which are also syncretistic. Notable "atheists" are Paul-Louis Couchoud, Earl Doherty,[q 1] Thomas L. Brodie, and Richard Carrier.[q 4][q 5]

Some other authors argue for the Jesus agnosticism viewpoint. That is, whether there was a historical Jesus is unknowable and if he did exist, close to nothing can be known about him.[10] Notable "agnosticists" are Robert Price and Thomas L. Thompson.[72][73] According to Thompson, the question of the historicity of Jesus also is not relevant for the understanding of the meaning and function of the Biblical texts in their own times.[72][73]

Overview of main mythicist arguments

According to New Testament scholar Robert Van Voorst, most Christ mythicists follow a threefold argument first set forward by German historian Bruno Bauer in the 1800s: they question the reliability of the Pauline epistles and the Gospels to postulate a historically existing Jesus; they note the lack of information on Jesus in non-Christian sources from the first and early second century; and they argue that early Christianity had syncretistic and mythological origins.[74] More specifically,

- Paul's epistles lack detailed biographical information – most mythicists argue that the Pauline epistles are older than the gospels but, aside from a few passages which may have been interpolations, there is a complete absence of any detailed biographical information such as might be expected if Jesus had been a contemporary of Paul,[75] nor do they cite any sayings from Jesus, the so-called argument from silence.[76][77][78][q 6] Some mythicists have argued that the Pauline epistles are from a later date than usually assumed, and therefore not a reliable source on the life of Jesus.[79][81][82]

- The Gospels are not historical records, but a fictitious historical narrative – mythicists argue that although the Gospels seem to present a historical framework, they are not historical records, but theological writings,[83][84] myth or legendary fiction resembling the Hero archetype.[85][86] They impose "a fictitious historical narrative" on a "mythical cosmic savior figure",[87][77] weaving together various pseudo-historical Jesus traditions,[88][89] though there may have been a real historical person, of whom close to nothing can be known.[90]

- There are no independent eyewitness accounts – No independent eyewitness accounts survive, in spite of the fact that many authors were writing at that time.[91][87] Early second-century Roman accounts contain very little evidence[11][92] and may depend on Christian sources.[93][94][83][95]

- Jesus was a mythological being, who was concretized in the Gospels – early Christianity was widely diverse and syncretistic, sharing common philosophical and religious ideas with other religions of the time.[96] It arose in the Greco-Roman world of the first and second century AD, synthesizing Greek Stoicism and Neoplatonism with Jewish Old Testament writings[97][98][73] and the exegetical methods of Philo,[11][96][99] creating the mythological figure of Jesus. Paul refers to Jesus as an exalted being, and is probably writing about either a mythical[77] or supernatural entity,[q 3] a celestial deity[q 7] named Jesus.[100][101][102][web 10] This celestial being is derived from personified aspects of God, notably the personification of Wisdom, or "a savior figure patterned after similar figures within ancient mystery religions,"[q 8][103][q 9] which were often (but not always) a dying-and-rising god.[2][104][105] While Paul may also contain proto-Gnostic ideas,[106][107] some mythicists have argued that Paul may refer to a historical person who may have lived in a dim past, long before the beginnings of the Common Era.[69][70][71]

Mainstream and mythicist views on the arguments

Mainstream view

The mainstream view is that the seven undisputed Pauline epistles considered by scholarly consensus to be genuine epistles are generally dated to AD 50–60 and are the earliest surviving Christian texts that include information about Jesus.[108][q 10] Most scholars view the Pauline letters as essential elements in the study of the historical Jesus,[108][109][110][111] and the development of early Christianity.[13] Yet, scholars have also argued that Paul was a "mythmaker",[112] who gave his own divergent interpretation of the meaning of Jesus,[13] building a bridge between the Jewish and Hellenistic world,[13] thereby creating the faith that became Christianity.[112]

Mythicist view

Mythicists agree on the importance of the Pauline epistles, some agreeing with this early dating, and taking the Pauline epistles as their point of departure from mainstream scholarship.[77] They argue that those letters actually point solely into the direction of a celestial or mythical being, or contain no definitive information on an historical Jesus. Some mythicists, though, have questioned the early dating of the epistles, raising the possibility that they represent a later, more developed strand of early Christian thought.

Theologian Willem Christiaan van Manen of the Dutch school of radical criticism noted various anachronisms in the Pauline epistles. Van Manen claimed that they could not have been written in their final form earlier than the 2nd century. He also noted that the Marcionite school was the first to publish the epistles, and that Marcion (c. 85 – c. 160) used them as justification for his gnostic and docetic views that Jesus' incarnation was not in a physical body. Van Manen also studied Marcion's version of Galatians in contrast to the canonical version, and argued that the canonical version was a later revision which de-emphasized the Gnostic aspects.[113]

Price also argues for a later dating of the epistles, and sees them as a compilation of fragments (possibly with a Gnostic core),[114] contending that Marcion was responsible for much of the Pauline corpus or even wrote the letters himself. Price criticizes his fellow Christ myth theorists for holding the mid-first-century dating of the epistles for their own apologetical reasons.[115][note 6]

Mainstream view

According to Eddy and Boyd, modern biblical scholarship notes that "Paul has relatively little to say on the biographical information of Jesus", viewing Jesus as "a recent contemporary".[117][118] Yet, according to Christopher Tuckett, "[e]ven if we had no other sources, we could still infer some things about Jesus from Paul's letters."[119][note 2]

Mythicist view

Wells, a "minimal mythicist", criticized the infrequency of the reference to Jesus in the Pauline letters and has said there is no information in them about Jesus' parents, place of birth, teachings, trial nor crucifixion.[120] Robert Price says that Paul does not refer to Jesus' earthly life, also not when that life might have provided convenient examples and justifications for Paul's teachings. Instead, revelation seems to have been a prominent source for Paul's knowledge about Jesus.[68]

Wells says that the Pauline epistles do not make reference to Jesus' sayings, or only in a vague and general sense. According to Wells, as referred to by Price in his own words, the writers of the New Testament "must surely have cited them when the same subjects came up in the situations they addressed".[121]

Mainstream view

Among contemporary scholars, there is consensus that the gospels are a type of ancient biography,[122][123][124][125][126][note 7] a genre which was concerned with providing examples for readers to emulate while preserving and promoting the subject's reputation and memory, as well as including propaganda and kerygma (preaching) in their works.[127][note 8]

Biblical scholarship regards the Gospels to be the literary manifestation of oral traditions which originated during the life of a historical Jesus, who according to Dunn had a profound impact on his followers.[131]

Mythicist view

Mythicists argue that in the gospels "a fictitious historical narrative" was imposed on the "mythical cosmic savior figure" created by Paul.[87] According to Robert Price, the Gospels "smack of fictional composition",[web 11] arguing that the Gospels are a type of legendary fiction[85] and that the story of Jesus portrayed in the Gospels fits the mythic hero archetype.[85][86] The mythic hero archetype is present in many cultures who often have miraculous conceptions or virgin births heralded by wise men and marked by a star, are tempted by or fight evil forces, die on a hill, appear after death and then ascend to heaven.[132] Some myth proponents suggest that some parts of the New Testament were meant to appeal to Gentiles as familiar allegories rather than history.[133] According to Earl Doherty, the gospels are "essentially allegory and fiction".[134]

According to Wells, a minimally historical Jesus existed, whose teachings were preserved in the Q document.[135] According to Wells, the Gospels weave together two Jesus narratives, namely this Galilean preacher of the Q document, and Paul's mythical Jesus.[135] Doherty disagrees with Wells regarding this teacher of the Q-document, arguing that he was an allegorical character who personified Wisdom and came to be regarded as the founder of the Q-community.[88][136] According to Doherty, Q's Jesus and Paul's Christ were combined in the Gospel of Mark by a predominantly Gentile community.[88]

Mainstream criticism

Ehrman notes that the gospels are based on oral sources, which played a decisive role in attracting new converts.[137]

Christian theologians have cited the mythic hero archetype as a defense of Christian teaching while completely affirming a historical Jesus.[138][139] Secular academics Kendrick and McFarland have also pointed out that the teachings of Jesus marked "a radical departure from all the conventions by which heroes had been defined".[140]

Mythicist view

Myth proponents claim there is significance in the lack of surviving historic records about Jesus of Nazareth from any non-Jewish author until the second century,[141][142][q 11] adding that Jesus left no writings or other archaeological evidence.[143] Using the argument from silence, they note that Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria did not mention Jesus when he wrote about the cruelty of Pontius Pilate around 40 AD.[144]

Mainstream criticism

Mainstream biblical scholars point out that much of the writings of antiquity have been lost[145] and that there was little written about any Jew or Christian in this period.[146][147] Ehrman points out that there is no known archaeological or textual evidence for the existence of most people in the ancient world, even famous people like Pontius Pilate, whom the myth theorists agree to have existed.[146] Robert Hutchinson notes that this is also true of Josephus, despite the fact that he was "a personal favorite of the Roman Emperor Vespasian".[148] Hutchinson quotes Ehrman, who notes that Josephus is never mentioned in 1st century Greek and Roman sources, despite being "a personal friend of the emperor".[148] According to Classical historian and popular author Michael Grant, if the same criterion is applied to others: "We can reject the existence of a mass of pagan personages whose reality as historical figures is never questioned."[149]

Josephus and Tacitus

There are three non-Christian sources which are typically used to study and establish the historicity of Jesus, namely two mentions in Josephus, and one mention in the Roman source Tacitus.[150][151][152][153][154]

Mainstream view

Josephus' Antiquities of the Jews, written around 93–94 AD, includes two references to the biblical Jesus in Books 18 and 20. The general scholarly view is that while the longer passage in book 18, known as the Testimonium Flavianum, is most likely not authentic in its entirety, it originally consisted of an authentic nucleus, which was then subject to Christian interpolation or forgery.[155][156][157] According to Josephus scholar Louis H. Feldman, "few have doubted the genuineness" of Josephus' reference to Jesus in Antiquities 20, 9, 1 ("the brother of Jesus, who was called Christ, whose name was James") and it is only disputed by a small number of scholars.[158][159][160][161]

Myth proponents argue that the Testimonium Flavianum may have been a partial interpolation or forgery by Christian apologist Eusebius in the 4th century or by others.[162][163][note 9] Richard Carrier further argues that the original text of Antiquities 20 referred to a brother of the high priest Jesus son of Damneus, named James, and not to Jesus Christ.[168] Carrier further argues that the words "the one called Christ" likely resulted from the accidental insertion of a marginal note added by some unknown reader.[168]

Roman historian Tacitus referred to "Christus" and his execution by Pontius Pilate in his Annals (written c. AD 116), book 15, chapter 44[169][note 10] The very negative tone of Tacitus' comments on Christians make most experts believe that the passage is extremely unlikely to have been forged by a Christian scribe.[153] The Tacitus reference is now widely accepted as an independent confirmation of Christ's crucifixion,[171] although some scholars question the historical value of the passage on various grounds.[172][173]

Mythicist view

Christ myth theory supporters such as G. A. Wells and Carrier contend that sources such as Tacitus and others, which were written decades after the supposed events, include no independent traditions that relate to Jesus, and hence can provide no confirmation of historical facts about him.[93][94][83][95]

Mainstream view

In Jesus Outside the New Testament (2000), mainstream scholar Van Voorst considers references to Jesus in classical writings, Jewish writings, hypothetical sources of the canonical Gospels, and extant Christian writings outside the New Testament. Van Voorst concludes that non-Christian sources provide "a small but certain corroboration of certain New Testament historical traditions on the family background, time of life, ministry, and death of Jesus", as well as "evidence of the content of Christian preaching that is independent of the New Testament", while extra-biblical Christian sources give access to "some important information about the earliest traditions on Jesus". However, New Testament sources remain central for "both the main lines and the details about Jesus' life and teaching".[174]

Jesus was a mythical being

Mainstream view

Most historians agree that Jesus or his followers established a new Jewish sect, one that attracted both Jewish and gentile converts. Out of this Jewish sect developed Early Christianity, which was very diverse, with proto-orthodoxy and "heretical" views like gnosticism alongside each other, [175][18] According to New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman, a number of early Christianities existed in the first century CE, from which developed various Christian traditions and denominations, including proto-orthodoxy.[176] According to theologian James D. G. Dunn, four types of early Christianity can be discerned: Jewish Christianity, Hellenistic Christianity, Apocalyptic Christianity, and early Catholicism.[177]

Mythicist view

In Christ and the Caesars (1877), philosopher Bruno Bauer suggested that Christianity was a synthesis of the Stoicism of Seneca the Younger, Greek Neoplatonism, and the Jewish theology of Philo as developed by pro-Roman Jews such as Josephus. This new religion was in need of a founder and created its Christ.[178][11] In a review of Bauer's work, Robert Price notes that Bauer's basic stance regarding the Stoic tone and the fictional nature of the Gospels are still repeated in contemporary scholarship.[web 11]

Doherty notes that, with the conquests of Alexander the Great, the Greek culture and language spread throughout the eastern Mediterranean world, influencing the already existing cultures there.[96] The Roman conquest of this area added to the cultural diversity, but also to a sense of alienation and pessimism.[96] A rich diversity of religious and philosophical ideas was available and Judaism was held in high regard by non-Jews for its monotheistic ideas and its high moral standards.[96] Yet monotheism was also offered by Greek philosophy, especially Platonism, with its high God and the intermediary Logos.[96] According to Doherty, "Out of this rich soil of ideas arose Christianity, a product of both Jewish and Greek philosophy",[96] echoing Bruno Bauer, who argued that Christianity was a synthesis of Stoicism, Greek Neoplatonism and Jewish thought.[11]

Robert Price notes that Christianity started among Hellenized Jews, who mixed allegorical interpretations of Jewish traditions with Jewish Gnostic, Zoroastrian, and mystery cult elements.[179][107][q 12] Some myth proponents note that some stories in the New Testament seem to try to reinforce Old Testament prophecies[133] and repeat stories about figures like Elijah, Elisha,[180] Moses and Joshua in order to appeal to Jewish converts.[181] Price notes that almost all the Gospel-stories have parallels in Old Testamentical and other traditions, concluding that the Gospels are no independent sources for a historical Jesus, but "legend and myth, fiction and redaction".[182]

According to Doherty, the rapid growth of early Christian communities and the great variety of ideas cannot be explained by a single missionary effort, but points to parallel developments, which arose at various places and competed for support. Paul's arguments against rival apostles also point to this diversity.[96] Doherty further notes that Yeshua (Jesus) is a generic name, meaning "Yahweh saves" and refers to the concept of divine salvation, which could apply to any kind of saving entity or Wisdom.[96]

Paul's Jesus is a celestial being

Mainstream view

According to mainstream scholarship, Jesus was an eschatological preacher or teacher, who was exalted after his death.[183][41] The Pauline letters incorporate creeds, or confessions of faith, that predate Paul, and give essential information on the faith of the early Jerusalem community around James, 'the brother of Jesus'.[184][185][186][13] These pre-Pauline creeds date to within a few years of Jesus' death and developed within the Christian community in Jerusalem.[187] The First Epistle to the Corinthians contains one of the earliest Christian creeds[188] expressing belief in the risen Jesus, namely 1 Corinthians 15:3–41:[189][190]

For I handed on to you as of first importance what I in turn had received: that Christ died for our sins in accordance with the scriptures,[note 11] and that he was buried, and that he was raised on the third day in accordance with the scriptures,[note 12] and that he appeared to Cephas, then to the twelve. Then he appeared to more than five hundred brothers and sisters at one time, most of whom are still alive, though some have died. Then he appeared to James, then to all the apostles. Last of all, as to one untimely born, he appeared also to me.[195]

New Testament scholar James Dunn states that in 1 Corinthians 15:3 Paul "recites the foundational belief", namely "that Christ died". According to Dunn, "Paul was told about a Jesus who had died two years earlier or so."[196] 1 Corinthians 15:11 also refers to others before Paul who preached the creed.[186]

According to Hurtado, Jesus' death was interpreted as a redemptive death "for our sins," in accordance with God's plan as contained in the Jewish scriptures.[197][note 11] The significance lay in "the theme of divine necessity and fulfillment of the scriptures," not in the later Pauline emphasis on "Jesus' death as a sacrifice or an expiation for our sins."[198] For the early Jewish Christians, "the idea that Messiah's death was a necessary redemptive event functioned more as an apologetic explanation for Jesus' crucifixion"[198] "proving that Jesus' death was no surprise to God."[199][note 13] According to Krister Stendahl, the main concern of Paul's writings on Jesus' role, and salvation by faith, is not the individual conscience of human sinners, and their doubts about being chosen by God or not, but the problem of the inclusion of gentile (Greek) Torah observers into God's covenant.[201][202][203][204][web 13][note 14]

The appearances of Jesus are often explained as visionary experiences, in which the presence of Jesus was felt.[205][206][207][208][209][210] According to Ehrman, the visions of Jesus and the subsequent belief in Jesus' resurrection radically changed the perceptions of his early followers, concluding from his absence that he must have been exalted to heaven, by God himself, exalting him to an unprecedented status and authority.[211] According to Hurtado, the resurrection experiences were religious experiences which "seem to have included visions of (and/or ascents to) God's heaven, in which the glorified Christ was seen in an exalted position".[212] These visions may mostly have appeared during corporate worship.[208] Johan Leman contends that the communal meals provided a context in which participants entered a state of mind in which the presence of Jesus was felt.[209]

The Pauline creeds contain elements of a Christ myth and its cultus,[213] such as the Christ hymn of Philippians 2:6–11,[note 15] which portrays Jesus as an incarnated and subsequently exalted heavenly being.[101][note 16] Scholars view these as indications that the incarnation and exaltation of Jesus was part of Christian tradition a few years after his death and over a decade before the writing of the Pauline epistles.[41][215][note 17]

Recent scholarship places the exaltation and devotion of Christ firmly in a Jewish context. Andrew Chester argues that "for Paul, Jesus is clearly a figure of the heavenly world, and thus fits a messianic category already developed within Judaism, where the Messiah is a human or angelic figure belonging ... in the heavenly world, a figure who at the same time has had specific, limited role on earth".[219] According to Ehrman, Paul regarded Jesus to be an angel, who was incarnated on earth.[41][note 18][note 19] According to James Waddell, Paul's conception of Jesus as a heavenly figure was influenced by the Book of Henoch and its conception of the Messiah.[223][web 15][note 20]

Mythicist views

Christ myth theorists generally reject the idea that Paul's epistles refer to a real person.[note 21][120] According to Doherty, the Jesus of Paul was a divine Son of God, existing in a spiritual realm[77] where he was crucified and resurrected.[225] This mythological Jesus was based on exegesis of the Old Testament and mystical visions of a risen Jesus.[225]

According to Carrier, the genuine Pauline epistles show that the Apostle Peter and the Apostle Paul believed in a visionary or dream Jesus, based on a pesher of Septuagint verses Zechariah 6 and 3, Daniel 9 and Isaiah 52–53.[226] Carrier notes that there is little if any concrete information about Christ's earthly life in the Pauline epistles, even though Jesus is mentioned over three hundred times.[227] According to Carrier, originally "Jesus was the name of a celestial being, subordinate to God,"[228] a "dying-and-rising" savior God like Mithras and Osiris, who "obtain[ed] victory over death" in this celestial realm.[228] According to Carrier "[t]his 'Jesus' would most likely have been the same archangel identified by Philo of Alexandria as already extant in Jewish theology",[229] which Philo knew by all of the attributes Paul also knew Jesus by.[note 22] According to Carrier, Philo says this being was identified as the figure named Jesus in the Book of Zechariah, implying that "already before Christianity there were Jews aware of a celestial being named Jesus who had all of the attributes the earliest Christians were associating with their celestial being named Jesus".[web 10]

Raphael Lataster, following Carrier, also argues that "Jesus began as a celestial messiah that certain Second Temple Jews already believed in, and was later allegorised in the Gospels."[230]

Mainstream criticism

Ehrman notes that Doherty, like many other mythicists, "quotes professional scholars at length when their views prove useful for developing aspects of his argument, but he fails to point out that not a single of these scholars agrees with his overarching thesis."[231] Ehrman has specifically criticized Doherty for misquoting scholarly sources as if in support of his celestial being-hypothesis, whereas those sources explicitly "[refer] to Christ becoming a human being in flesh on earth – precisely the view he rejects."[web 17]

James McGrath criticizes Carrier, stating that Carrier is ignoring the details, and that "Philo is offering an allusive reference to, and allegorical treatment of, a text in Zechariah which mentioned a historical high priest named Joshua."[web 18]

According to Hurtado, for Paul and his contemporaries Jesus was a human being, who was exaltated as Messiah and Lord after his crucifixion.[web 19] According to Hurtado, "There is no evidence whatsoever of a 'Jewish archangel Jesus' in any of the second-temple Jewish evidence [...] Instead, all second-temple instances of the name are for historical figures."[web 19] Hurtado rejects Carrier's claim that "Philo of Alexandria mentions an archangel named 'Jesus'." According to Hurtado, Philo mentions a priestly figure called Joshua, and a royal personage whose name can be interpreted as "rising," among other connotations. According to Hurtado, there is no "Jesus Rising" in either Zechariah nor Philo, stating that Carrier is incorrect.[web 20][web 21][note 23]

Ehrman notes that "there were no Jews prior to Christianity who thought that Isaiah 53 (or any of the other "suffering" passages) referred to the future messiah."[232] Only after his painful death were these texts used to interpret his suffering in a meaningful way,[232] though "Isaiah is not speaking about the future messiah, and he was never interpreted by any Jews prior to the first century as referring to the messiah."[233][note 24]

Simon Gathercole at Cambridge also evaluated the mythicist arguments for the claim that Paul believed in a heavenly, celestial Jesus who was never on Earth. Gathercole concludes that Carrier's arguments, and more broadly, the mythicist positions on different aspects of Paul's letters are contradicted by the historical data, and that Paul says a number of things regarding Jesus' life on Earth, his personality, family, etc.[234]

Parallels with saviour gods

Mainstream view

Jesus has to be understood in the Palestinian and Jewish context of the first century CE.[36][37][38] Most of the themes, epithets, and expectations formulated in the New Testamentical literature have Jewish origins, and are elaborations of these themes. According to Hurtado, Roman-era Judaism refused "to worship any deities other than the God of Israel," including "any of the adjutants of the biblical God, such as angels, messiahs, etc."[web 22] The Jesus-devotion which emerged in early Christianity has to be regarded as a specific, Christian innovation in the Jewish context.[web 22]

Mythicist view

According to Wells, Doherty, and Carrier, the mythical Jesus was derived from Wisdom traditions, the personification of an eternal aspect of God, who came to visit human beings.[235][236][237][web 23] Wells "regard[s] this Jewish Wisdom literature as of great importance for the earliest Christian ideas about Jesus".[235] Doherty notes that the concept of a spiritual Christ was the result of common philosophical and religious ideas of the first and second century AD, in which the idea of an intermediary force between God and the world were common.[77]

According to Doherty, the Christ of Paul shares similarities with the Greco-Roman mystery cults.[77] Authors Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy explicitly argue that Jesus was a deity, akin to the mystery cults,[238] while Dorothy Murdock argues that the Christ myth draws heavily on the Egyptian story of Osiris and Horus.[239] According to Carrier, early Christianity was but one of several mystery cults which developed out of Hellenistic influences on local cults and religions.[228]

Wells and Alvar Ellegård, have argued that Paul's Jesus may have lived far earlier, in a dimly remembered remote past.[69][70][71] Wells argues that Paul and the other epistle writers—the earliest Christian writers—do not provide any support for the idea that Jesus lived early in the 1st century and that—for Paul—Jesus may have existed many decades, if not centuries, before.[120][240] According to Wells, the earliest strata of the New Testament literature presented Jesus as "a basically supernatural personage only obscurely on Earth as a man at some unspecified period in the past".[241]

According to Price, the Toledot Yeshu places Jesus "about 100 BCE", while Epiphanius of Salamis and the Talmud make references to "Jewish and Jewish-Christian belief" that Jesus lived about a century earlier than usually assumed. According to Price, this implies that "perhaps the Jesus figure was at first an ahistorical myth and various attempts were made to place him in a plausible historical context, just as Herodotus and others tried to figure out when Hercules 'must have' lived".[242][note 26]

Mainstream criticism

Mainstream scholarship disagrees with these interpretations, and regards them as outdated applications of ideas and methodologies from the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule. According to Philip Davies, the Jesus of the New Testament is indeed "composed of stock motifs (and mythic types) drawn from all over the Mediterranean and Near Eastern world". Yet, this does not mean that Jesus was "invented"; according to Davies, "the existence of a guru of some kind is more plausible and economical than any other explanation".[web 5] Ehrman states that mythicists make too much of the perceived parallels with pagan religions and mythologies. According to Ehrman, critical-historical research has clearly shown the Jewish roots and influences of Christianity.[54]

Many mainstream biblical scholars respond that most of the perceived parallels with mystery religions are either coincidences or without historical basis and/or that these parallels do not prove that a Jesus figure did not live.[246][note 27] Boyd and Eddy doubt that Paul viewed Jesus similar to the savior deities found in ancient mystery religions.[251] Ehrman notes that Doherty proposes that the mystery cults had a neo-Platonic cosmology, but that Doherty gives no evidence for this assertion.[252] Furthermore, "the mystery cults are never mentioned by Paul or by any other Christian author of the first hundred years of the Church," nor did they play a role in the worldview of any of the Jewish groups of the first century.[253]

Theologian Gregory A. Boyd and Paul Rhodes Eddy, Professor of Biblical and Theological Studies at Bethel University,[254] criticise the idea that "Paul viewed Jesus as a cosmic savior who lived in the past", referring to various passages in the Pauline epistles which seem to contradict this idea. In Galatians 1:19, Paul says he met with James, the "Lord's brother"; 1 Corinthians 15:3–8 refers to people to whom Jesus' had appeared, and who were Paul's contemporaries; and in 1 Thessalonians 2:14–16 Paul refers to the Jews "who both killed the Lord Jesus" and "drove out us" as the same people, indicating that the death of Jesus was within the same time frame as the persecution of Paul.[255]

Late 18th to early 20th century

According to Van Voorst, "The argument that Jesus never existed, but was invented by the Christian movement around the year 100, goes back to Enlightenment times, when the historical-critical study of the past was born", and may have originated with Lord Bolingbroke, an English deist.[256]

According to Weaver and Schneider, the beginnings of the formal denial of the existence of Jesus can be traced to late 18th-century France with the works of Constantin François Chassebœuf de Volney and Charles-François Dupuis.[257][258] Volney and Dupuis argued that Christianity was an amalgamation of various ancient mythologies and that Jesus was a totally mythical character.[257][259] Dupuis argued that ancient rituals in Syria, Egypt, Mesopotamia, Persia, and India had influenced the Christian story which was allegorized as the histories of solar deities, such as Sol Invictus.[260] Dupuis also said that the resurrection of Jesus was an allegory for the growth of the sun's strength in the sign of Aries at the spring equinox.[260] Volney argued that Abraham and Sarah were derived from Brahma and his wife Saraswati, whereas Christ was related to Krishna.[261][262] Volney made use of a draft version of Dupuis' work and at times differed from him, e.g. in arguing that the gospel stories were not intentionally created, but were compiled organically.[260] Volney's perspective became associated with the ideas of the French Revolution, which hindered the acceptance of these views in England.[263] Despite this, his work gathered significant following among British and American radical thinkers during the 19th century.[263]

In 1835, German theologian David Friedrich Strauss published his extremely controversial The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined (Das Leben Jesu). While not denying that Jesus existed, he did argue that the miracles in the New Testament were mythical additions with little basis in actual fact.[264][265][266] According to Strauss, the early church developed these stories in order to present Jesus as the Messiah of the Jewish prophecies. This perspective was in opposition to the prevailing views of Strauss' time: rationalism, which explained the miracles as misinterpretations of non-supernatural events, and the supernaturalist view that the biblical accounts were entirely accurate. Strauss's third way, in which the miracles are explained as myths developed by early Christians to support their evolving conception of Jesus, heralded a new epoch in the textual and historical treatment of the rise of Christianity.[264][265][266]

German Bruno Bauer, who taught at the University of Bonn, took Strauss' arguments further and became the first author to systematically argue that Jesus did not exist.[267][268] Beginning in 1841 with his Criticism of the Gospel History of the Synoptics, Bauer argued that Jesus was primarily a literary figure, but left open the question of whether a historical Jesus existed at all. Then in his Criticism of the Pauline Epistles (1850–1852) and in A Critique of the Gospels and a History of their Origin (1850–1851), Bauer argued that Jesus had not existed.[269] Bauer's work was heavily criticized at the time, as in 1839 he was removed from his position at the University of Bonn and his work did not have much impact on future myth theorists.[267][270]

In his two-volume, 867-page book Anacalypsis (1836), English gentleman Godfrey Higgins said that "the mythos of the Hindus, the mythos of the Jews and the mythos of the Greeks are all at bottom the same; and are contrivances under the appearance of histories to perpetuate doctrines"[271] and that Christian editors "either from roguery or folly, corrupted them all".[272] In his 1875 book The World's Sixteen Crucified Saviors, American Kersey Graves said that many demigods from different countries shared similar stories, traits or quotes as Jesus and he used Higgins as the main source for his arguments. The validity of the claims in the book have been greatly criticized by Christ myth proponents like Richard Carrier and largely dismissed by biblical scholars.[273]

Starting in the 1870s, English poet and author Gerald Massey became interested in Egyptology and reportedly taught himself Egyptian hieroglyphics at the British Museum.[274] In 1883, Massey published The Natural Genesis where he asserted parallels between Jesus and the Egyptian god Horus. His other major work, Ancient Egypt: The Light of the World, was published shortly before his death in 1907. His assertions have influenced various later writers such as Alvin Boyd Kuhn and Tom Harpur.[275]

In the 1870s and 1880s, a group of scholars associated with the University of Amsterdam, known in German scholarship as the Radical Dutch school, rejected the authenticity of the Pauline epistles and took a generally negative view of the Bible's historical value.[276] Abraham Dirk Loman argued in 1881 that all New Testament writings belonged to the 2nd century and doubted that Jesus was a historical figure, but later said the core of the gospels was genuine.[277]

Additional early Christ myth proponents included Swiss skeptic Rudolf Steck,[278] English historian Edwin Johnson,[279] English radical Reverend Robert Taylor and his associate Richard Carlile.[280][281]

During the early 20th century, several writers published arguments against Jesus' historicity, often drawing on the work of liberal theologians, who tended to deny any value to sources for Jesus outside the New Testament and limited their attention to Mark and the hypothetical Q source.[277] They also made use of the growing field of religious history which found sources for Christian ideas in Greek and Oriental mystery cults, rather than Judaism.[282][note 28]

The work of social anthropologist Sir James George Frazer has had an influence on various myth theorists, although Frazer himself believed that Jesus existed.[284] In 1890, Frazer published the first edition of The Golden Bough which attempted to define the shared elements of religious belief. This work became the basis of many later authors who argued that the story of Jesus was a fiction created by Christians. After a number of people claimed that he was a myth theorist, in the 1913 expanded edition of The Golden Bough he expressly stated that his theory assumed a historical Jesus.[285]

In 1900, Scottish Member of Parliament John Mackinnon Robertson argued that Jesus never existed, but was an invention by a first-century messianic cult of Joshua, whom he identifies as a solar deity.[286][287][286][287] The English school master George Robert Stowe Mead argued in 1903 that Jesus had existed, but that he had lived in 100 BC.[288][289] Mead based his argument on the Talmud, which pointed to Jesus being crucified c. 100 BC. In Mead's view, this would mean that the Christian gospels are mythical.[290]

In 1909, school teacher John Eleazer Remsburg published The Christ, which made a distinction between a possible historical Jesus (Jesus of Nazareth) and the Jesus of the Gospels (Jesus of Bethlehem). Remsburg thought that there was good reason to believe that the historical Jesus existed, but that the "Christ of Christianity" was a mythological creation.[291] Remsburg compiled a list of 42 names of "writers who lived and wrote during the time, or within a century after the time" who Remsburg felt should have written about Jesus if the Gospels account was reasonably accurate, but who did not.[292]

Also in 1909, German philosophy Professor Christian Heinrich Arthur Drews wrote The Christ Myth to argue that Christianity had been a Jewish Gnostic cult that spread by appropriating aspects of Greek philosophy and life-death-rebirth deities.[293] In his later books The Witnesses to the Historicity of Jesus (1912) and The Denial of the Historicity of Jesus in Past and Present (1926), Drews reviewed the biblical scholarship of his time as well as the work of other myth theorists, attempting to show that everything reported about the historical Jesus had a mythical character.[294][note 29]

Revival (1970s–present)

Beginning in the 1970s, in the aftermath of the second quest for the historical Jesus, interest in the Christ myth theory was revived by George Albert Wells, whose ideas were elaborated by Earl Doherty. With the rise of the internet in the 1990s, their ideas gained popular interest, giving way to a multitude of publications and websites aimed at a popular audience, most notably Richard Carrier, often taking a polemical stance toward Christianity. Their ideas are supported by Robert Price, an academic theologian, while somewhat different stances on the mythological origins are offered by Thomas L. Thompson and Thomas L. Brodie, both also accomplished scholars in theology.

Paul-Louis Couchoud

The French philosopher Paul-Louis Couchoud,[299] published in the 1920s and 1930s, was a predecessor for contemporary mythicists. According to Couchoud, Christianity started not with a biography of Jesus but "a collective mystical experience, sustaining a divine history mystically revealed".[300] Couchaud's Jesus is not a "myth", but a "religious conception".[301]

Robert Price mentions Couchoud's comment on the Christ Hymn, one of the relics of the Christ cults to which Paul converted. Couchoud noted that in this hymn the name Jesus was given to the Christ after his torturous death, implying that there cannot have been a ministry by a teacher called Jesus.

George Albert Wells

George Albert Wells (1926–2017), a professor of German, revived the interest in the Christ myth theory. In his early work,[302] including Did Jesus Exist? (1975), Wells argued that because the Gospels were written decades after Jesus's death by Christians who were theologically motivated but had no personal knowledge of him, a rational person should believe the gospels only if they are independently confirmed.[303] In The Jesus Myth (1999) and later works, Wells argues that two Jesus narratives fused into one, namely Paul's mythical Jesus, and a minimally historical Jesus from a Galilean preaching tradition, whose teachings were preserved in the Q document, a hypothetical common source for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke.[135][304] According to Wells, both figures owe much of their substance to ideas from the Jewish wisdom literature.[305]

In 2000 Van Voorst gave an overview of proponents of the "Nonexistence Hypothesis" and their arguments, presenting eight arguments against this hypothesis as put forward by Wells and his predecessors.[306][307] According to Maurice Casey, Wells' work repeated the main points of the Religionsgeschichtliche Schule, which are deemed outdated by mainstream scholarship. His works were not discussed by New Testament scholars, because it was "not considered to be original, and all his main points were thought to have been refuted long time ago, for reasons which were very well known".[67]

In his later writings, G.A Wells changed his mind and came to view Jesus as a minimally historical figure.[308]

Earl Doherty

Canadian writer Earl Doherty (born 1941) was introduced to the Christ myth theme by a lecture by Wells in the 1970s.[77] Doherty follows the lead of Wells, but disagrees on the historicity of Jesus, arguing that "everything in Paul points to a belief in an entirely divine Son who 'lived' and acted in the spiritual realm, in the same mythical setting in which all the other savior deities of the day were seen to operate".[77][note 30] According to Doherty, Paul's Christ originated as a myth derived from middle Platonism with some influence from Jewish mysticism and belief in a historical Jesus emerged only among Christian communities in the 2nd century.[134] Doherty agrees with Bauckham that the earliest Christology was already a "high Christology", that is, Jesus was an incarnation of the pre-existent Christ, but deems it "hardly credible" that such a belief could develop in such a short time among Jews.[311][note 17] Therefore, Doherty concludes that Christianity started with the myth of this incarnated Christ, who was subsequently historicised. According to Doherty, the nucleus of this historicised Jesus of the Gospels can be found in the Jesus-movement which wrote the Q source.[88] Eventually, Q's Jesus and Paul's Christ were combined in the Gospel of Mark by a predominantly gentile community.[88] In time, the gospel-narrative of this embodiment of Wisdom became interpreted as the literal history of the life of Jesus.[136]

Eddy and Boyd characterize Doherty's work as appealing to the "History of Religions School".[312] In a book criticizing the Christ myth theory, New Testament scholar Maurice Casey describes Doherty as "perhaps the most influential of all the mythicists",[313] but one who is unable to understand the ancient texts he uses in his arguments.[314]

Richard Carrier

American independent scholar[315] Richard Carrier (born 1969) reviewed Doherty's work on the origination of Jesus[316] and eventually concluded that the evidence favored the core of Doherty's thesis.[317] According to Carrier, following Couchoud and Doherty, Christianity started with the belief in a new deity called Jesus,[q 4] "a spiritual, mythical figure".[q 5] According to Carrier, this new deity was fleshed out in the Gospels, which added a narrative framework and Cynic-like teachings, and eventually came to be perceived as a historical biography.[q 4] Carrier argues in his book On the Historicity of Jesus: Why We Might Have Reason for Doubt that the Jesus figure was probably originally known only through private revelations and hidden messages in scripture which were then crafted into a historical figure to communicate the claims of the gospels allegorically. These allegories then started to be believed as fact during the struggle for control of the Christian churches of the first century.[318]

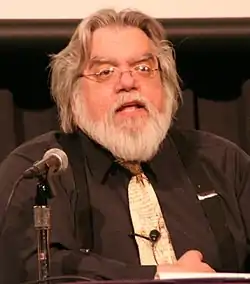

Robert M. Price

American New Testament scholar and former Baptist pastor Robert M. Price (born 1954) has questioned the historicity of Jesus in a series of books, including Deconstructing Jesus (2000), The Incredible Shrinking Son of Man (2003), Jesus Is Dead (2007) and The Christ-Myth Theory and Its Problems (2011). Price uses critical-historical methods,[319] but also uses "history-of-religions parallel[s]",[320] or the "Principle of Analogy",[321] to show similarities between Gospel narratives and non-Christian Middle Eastern myths.[322] Price criticises some of the criteria of critical Bible research, such as the criterion of dissimilarity[323] and the criterion of embarrassment.[324] Price further notes that "consensus is no criterion" for the historicity of Jesus.[325] According to Price, if critical methodology is applied with ruthless consistency, one is left in complete agnosticism regarding Jesus's historicity.[326][note 31]

In Deconstructing Jesus, Price claims that "the Jesus Christ of the New Testament is a composite figure", out of which a broad variety of historical Jesuses can be reconstructed, any one of which may have been the real Jesus, but not all of them together.[327] According to Price, various Jesus images flowed together at the origin of Christianity, some of them possibly based on myth, some of them possibly based on "a historical Jesus the Nazorean".[89] Price admits uncertainty in this regard, writing in conclusion: "There may have been a real figure there, but there is simply no longer any way of being sure".[328] In contributions to The Historical Jesus: Five Views (2009), he acknowledges that he stands against the majority view of scholars, but cautions against attempting to settle the issue by appeal to the majority.[329]

Thomas L. Thompson

Thomas L. Thompson (born 1939), Professor emeritus of theology at the University of Copenhagen, is a leading biblical minimalist of the Old Testament, and supports a mythicist position, according to Ehrman[q 13] and Casey.[q 14] According to Thompson, "questions of understanding and interpreting biblical texts" are more relevant than "questions about the historical existence of individuals such as ... Jesus".[72] In his 2007 book The Messiah Myth: The Near Eastern Roots of Jesus and David, Thompson argues that the Biblical accounts of both King David and Jesus of Nazareth are not historical accounts, but are mythical in nature and based on Mesopotamian, Egyptian, Babylonian and Greek and Roman literature.[330] Those accounts are based on the Messiah mytheme, a king anointed by God to restore the Divine order at Earth.[73] Thompson also argues that the resurrection of Jesus is taken directly from the story of the dying and rising god, Dionysus.[330] Thompson does not draw a final conclusion on the historicity or ahistoricity of Jesus, but states that "A negative statement, however, that such a figure did not exist, cannot be reached: only that we have no warrant for making such a figure part of our history."[73]

Thompson coedited the contributions from a diverse range of scholars in the 2012 book Is This Not the Carpenter?: The Question of the Historicity of the Figure of Jesus.[9][331] Writing in the introduction, "The essays collected in this volume have a modest purpose. Neither establishing the historicity of a historical Jesus nor possessing an adequate warrant for dismissing it, our purpose is to clarify our engagement with critical historical and exegetical methods."[332]

Ehrman has criticised Thompson, questioning his qualifications and expertise regarding New Testament research.[q 13] In a 2012 online article, Thompson defended his qualifications to address New Testament issues, and objected to Ehrman's statement that "[a] different sort of support for a mythicist position comes in the work of Thomas L. Thompson."[note 32] According to Thompson, "Bart Ehrman has attributed to my book arguments and principles which I had never presented, certainly not that Jesus had never existed", and reiterated his position that the issue of Jesus' existence cannot be determined one way or the other.[73] Thompson further states that Jesus is not to be regarded as "the notoriously stereotypical figure of ... (mistaken) eschatological prophet", as Ehrman does, but is modelled on "the royal figure of a conquering messiah", derived from Jewish writings.[73]

Thomas L. Brodie

In 2012, the Irish Dominican priest and theologian Thomas L. Brodie (born 1943), holding a PhD from the Pontifical University of St. Thomas Aquinas in Rome and a co-founder and former director of the Dominican Biblical Institute in Limerick, published Beyond the Quest for the Historical Jesus: Memoir of a Discovery. In this book, Brodie, who previously had published academic works on the Hebrew prophets, argued that the Gospels are essentially a rewriting of the stories of Elijah and Elisha when viewed as a unified account in the Books of Kings. This view lead Brodie to the conclusion that Jesus is mythical.[180] Brodie's argument builds on his previous work, in which he stated that rather than being separate and fragmented, the stories of Elijah and Elisha are united and that 1 Kings 16:29 – 2 Kings 13:25 is a natural extension of 1 Kings 17 – 2 Kings 8 which have a coherence not generally observed by other biblical scholars.[333] Brodie then views the Elijah–Elisha story as the underlying model for the gospel narratives.[333]

In response to Brodie's publication of his view that Jesus was mythical, the Dominican order banned him from writing and lecturing, although he was allowed to stay on as a brother of the Irish Province, which continued to care for him.[334] "There is an unjustifiable jump between methodology and conclusion" in Brodie's book—according to Gerard Norton—and "are not soundly based on scholarship". According to Norton, they are "a memoir of a series of significant moments or events" in Brodie's life that reinforced "his core conviction" that neither Jesus nor Paul of Tarsus were historical.[335]

Other modern proponents

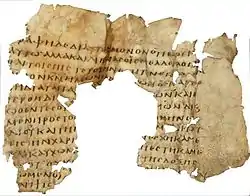

In his books The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970) and The Dead Sea Scrolls and the Christian Myth (1979), the British archaeologist and philologist John M. Allegro advanced the theory that stories of early Christianity originated in a shamanistic Essene clandestine cult centered around the use of hallucinogenic mushrooms.[336][337][338][339] He also argued that the story of Jesus was based on the crucifixion of the Teacher of Righteousness in the Dead Sea Scrolls.[340][341] Allegro's theory was criticised sharply by Welsh historian Philip Jenkins, who wrote that Allegro relied on texts that did not exist in quite the form he was citing them.[342] Based on this and many other negative reactions to the book, Allegro's publisher later apologized for issuing the book and Allegro was forced to resign his academic post.[338][343]

Alvar Ellegård, in The Myth of Jesus (1992), and Jesus: One Hundred Years Before Christ. A Study in Creative Mythology (1999), argued that Jesus lived 100 years before the accepted dates, and was a teacher of the Essenes. According to Ellegård, Paul was connected with the Essenes, and had a vision of this Jesus.

Timothy Freke and Peter Gandy, in their 1999 publication The Jesus Mysteries: Was the "Original Jesus" a Pagan God? propose that Jesus did not literally exist as an historically identifiable individual, but was instead a syncretic re-interpretation of the fundamental pagan "godman" by the Gnostics, who were the original sect of Christianity. The book has been negatively received by scholars, and also by Christ mythicists.[344][345][346]

Influenced by Massey and Higgins, Alvin Boyd Kuhn (1880–1963), an American Theosophist, argued an Egyptian etymology to the Bible that the gospels were symbolic rather than historic and that church leaders started to misinterpret the New Testament in the third century.[347] Building on Kuhn's work, author and ordained priest Tom Harpur in his 2004 book The Pagan Christ listed similarities among the stories of Jesus, Horus, Mithras, Buddha and others. According to Harpur, in the second or third centuries the early church created the fictional impression of a literal and historic Jesus and then used forgery and violence to cover up the evidence.[274][note 33]

In his 2017 book Décadence, French writer and philosopher Michel Onfray argued for the Christ myth theory and based his hypothesis on the fact that—other than in the New Testament—Jesus is barely mentioned in accounts of the period.[351]

The Christ myth theory enjoyed brief popularity in the Soviet Union, where it was supported by Sergey Kovalev, Alexander Kazhdan, Abram Ranovich, Nikolai Rumyantsev and Robert Vipper.[352] However, several scholars, including Kazhdan, later retracted their views about mythical Jesus and by the end of the 1980s Iosif Kryvelev remained as virtually the only proponent of Christ myth theory in Soviet academia.[353]

Reception

Lack of support for mythicism

In modern scholarship, the Christ myth theory is a fringe theory, which finds virtually no support from scholars,[4][354][5][6][355][q 2] to the point of being addressed in footnotes or almost completely ignored due to the obvious weaknesses they espouse.[356] However, more attention has been given to mythicism in recent years due to it recurring when people ask scholars like Bart Ehrman about it.[357] According to him, nearly all scholars who study the early Christian period believe that he did exist and Ehrman observes that mythicist writings are generally of poor quality because they are usually authored by amateurs and non-scholars who have no academic credentials or have never taught at academic institutions.[357] Maurice Casey, theologian and scholar of New Testament and early Christianity, stated that the belief among professors that Jesus existed is generally completely certain. According to Casey, the view that Jesus did not exist is "the view of extremists", "demonstrably false" and "professional scholars generally regard it as having been settled in serious scholarship long ago".[358]

In 1977, classical historian and popular author Michael Grant in his book Jesus: An Historian's Review of the Gospels, concluded that "modern critical methods fail to support the Christ-myth theory".[359] In support of this, Grant quoted Roderic Dunkerley's 1957 opinion that the Christ myth theory has "again and again been answered and annihilated by first-rank scholars".[360] At the same time, he also quoted Otto Betz's 1968 opinion that in recent years "no serious scholar has ventured to postulate the non-historicity of Jesus—or at any rate very few, and they have not succeeded in disposing of the much stronger, indeed very abundant, evidence to the contrary".[361] In the same book, he also wrote:

If we apply to the New Testament, as we should, the same sort of criteria as we should apply to other ancient writings containing historical material, we can no more reject Jesus' existence than we can reject the existence of a mass of pagan personages whose reality as historical figures is never questioned.[362]

Graeme Clarke, Emeritus Professor of Classical Ancient History and Archaeology at Australian National University[363] stated in 2008: "Frankly, I know of no ancient historian or biblical historian who would have a twinge of doubt about the existence of a Jesus Christ—the documentary evidence is simply overwhelming".[364] R. Joseph Hoffmann, who had created the Jesus Project, which included both mythicists and historicists to investigate the historicity of Jesus, wrote that an adherent to the Christ myth theory asked to set up a separate section of the project for those committed to the theory. Hoffmann felt that to be committed to mythicism signaled a lack of necessary skepticism and he noted that most members of the project did not reach the mythicist conclusion.[365]

Philip Jenkins, Distinguished Professor of History at Baylor University, has written "What you can’t do, though, without venturing into the far swamps of extreme crankery, is to argue that Jesus never existed. The “Christ-Myth Hypothesis” is not scholarship, and is not taken seriously in respectable academic debate. The grounds advanced for the “hypothesis” are worthless. The authors proposing such opinions might be competent, decent, honest individuals, but the views they present are demonstrably wrong....Jesus is better documented and recorded than pretty much any non-elite figure of antiquity."[366]

According to Gullotta, most of the mythicist literature contains "wild theories, which are poorly researched, historically inaccurate, and written with a sensationalist bent for popular audiences."[367]

Questioning the competence of proponents

Critics of the Christ myth theory question the competence of its supporters.[q 14] According to Ehrman:

Few of these mythicists are actually scholars trained in ancient history, religion, biblical studies or any cognate field, let alone in the ancient languages generally thought to matter for those who want to say something with any degree of authority about a Jewish teacher who (allegedly) lived in first-century Palestine.[368]

Maurice Casey has criticized the mythicists, pointing out their complete ignorance of how modern critical scholarship actually works. He also criticizes mythicists for their frequent assumption that all modern scholars of religion are Protestant fundamentalists of the American variety, insisting that this assumption is not only totally inaccurate, but also exemplary of the mythicists' misconceptions about the ideas and attitudes of mainstream scholars.[369]

Questioning the mainstream view appears to have consequences for one's job perspectives. According to Casey, Thompson's early work, which "successfully refuted the attempts of Albright and others to defend the historicity of the most ancient parts of biblical literature history", has "negatively affected his future job prospects".[q 14] Ehrman also notes that mythicist views would prevent one from getting employment in a religious studies department:

These views are so extreme and so unconvincing to 99.99 percent of the real experts that anyone holding them is as likely to get a teaching job in an established department of religion as a six-day creationist is likely to land on in a bona fide department of biology.[368]

Other criticisms

Robert Van Voorst has written "Contemporary New Testament scholars have typically viewed (Christ myth) arguments as so weak or bizarre that they relegate them to footnotes, or often ignore them completely [...] The theory of Jesus' nonexistence is now effectively dead as a scholarly question."[356] Paul L. Maier, former Professor of Ancient History at Western Michigan University and current professor emeritus in the Department of History there has stated "Anyone who uses the argument that Jesus never existed is simply flaunting his ignorance."[370] Among notable scholars who have directly addressed the Christ myth are Bart Ehrman, Maurice Casey and Philip Jenkins.

In 2000 Van Voorst gave an overview of proponents of the "Nonexistence Hypothesis" and their arguments, presenting eight arguments against this hypothesis as put forward by Wells and his predecessors.[306][307]

- The "argument of silence" is to be rejected, because "it is wrong to suppose that what is unmentioned or undetailed did not exist." Van Voorst further argues that the early Christian literature was not written for historical purposes.

- Dating the "invention" of Jesus around 100 CE is too late; Mark was written earlier, and contains abundant historical details which are correct.

- The argument that the development of the Gospel traditions shows that there was no historical Jesus is incorrect; "development does not prove wholesale invention, and difficulties do not prove invention."

- Wells cannot explain why "no pagans and Jews who opposed Christianity denied Jesus' historicity or even questioned it."

- The rejection of Tacitus and Josephus ignores the scholarly consensus.

- Proponents of the "Nonexistence Hypothesis" are not driven by scholarly interests, but by anti-Christian sentiments.

- Wells and others do not offer alternative "other, credible hypotheses" for the origins of Christianity.

- Wells himself accepted the existence of a minimal historical Jesus, thereby effectively leaving the "Nonexistence Hypothesis."

In his book Did Jesus Exist?, Bart Ehrman surveys the arguments "mythicists" have made against the existence of Jesus since the idea was first mooted at the end of the 18th century. As for the lack of contemporaneous records for Jesus, Ehrman notes no comparable Jewish figure is mentioned in contemporary records either and there are mentions of Christ in several Roman works of history from only decades after the death of Jesus.[371] The author states that the authentic letters of the apostle Paul in the New Testament were likely written within a few years of Jesus' death and that Paul likely personally knew James, the brother of Jesus. Although the gospel accounts of Jesus' life may be biased and unreliable in many respects, Ehrman writes, they and the sources behind them which scholars have discerned still contain some accurate historical information.[371] So many independent attestations of Jesus' existence, Ehrman says, are actually "astounding for an ancient figure of any kind".[368] Ehrman dismisses the idea that the story of Jesus is an invention based on pagan myths of dying-and-rising gods, maintaining that the early Christians were primarily influenced by Jewish ideas, not Greek or Roman ones,[368][371] and repeatedly insisting that the idea that there was never such a person as Jesus is not seriously considered by historians or experts in the field at all.[371]

Alexander Lucie-Smith, Catholic priest and doctor of moral theology, states that "People who think Jesus didn’t exist are seriously confused," but also notes that "the Church needs to reflect on its failure. If 40 per cent believe in the Jesus myth, this is a sign that the Church has failed to communicate with the general public."[372]

Stanley E. Porter, president and dean of McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, and Stephen J. Bedard, a Baptist minister and graduate of McMaster Divinity, respond to Harpur's ideas from an evangelical standpoint in Unmasking the Pagan Christ: An Evangelical Response to the Cosmic Christ Idea, challenging the key ideas lying at the foundation of Harpur's thesis. Porter and Bedard conclude that there is sufficient evidence for the historicity of Jesus and assert that Harpur is motivated to promote "universalistic spirituality".[373][note 34]

Popular reception

In a 2015 poll conducted by the Church of England, 40% of respondents indicated that they did not believe Jesus was a real person.[374]

Ehrman notes that "the mythicists have become loud, and thanks to the Internet they've attracted more attention".[375] Within a few years of the inception of the World Wide Web (c. 1990), mythicists such as Earl Doherty began to present their argument to a larger public via the internet.[q 15] Doherty created the website The Jesus Puzzle in 1996,[web 24] while the organization Internet Infidels has featured the works of mythicists on their website[376] and mythicism has been mentioned on several popular news sites.[377]

According to Derek Murphy, the documentaries The God Who Wasn't There (2005) and Zeitgeist (2007) raised interest for the Christ myth theory with a larger audience and gave the topic a large coverage on the Internet.[378] Daniel Gullotta notes the relationship between the organization "Atheists United" and Carrier's work related to Mythicism, which has increased "the attention of the public".[q 16]

According to Ehrman, mythicism has a growing appeal "because these deniers of Jesus are at the same time denouncers of religion".[368][q 17] According to Casey, mythicism has a growing appeal because of an aversion toward Christian fundamentalism among American atheists.[67]

Documentaries