Cincinnati Water Maze

The Cincinnati Water Maze (CWM) is a type of water maze. Water mazes are experimental equipment used in laboratories; they are mazes that are partially filled with water, and rodents are put in them to be observed and timed as they make their way through the maze. Generally two sets of rodents are put through the maze, one that has been treated, and another that has not, and the results are compared. The experimenter uses this type of maze to learn about the subject's cognitive or emotional processes.[1][2]

Overview

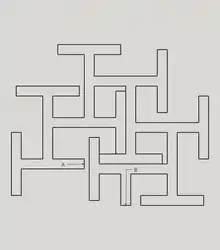

The Cincinnati Water Maze is a water maze that has nine interconnected T-intersections. The rats are forced to find to find their way from one end of the maze to the other by navigating through openings in the side of the walls rather than at the end of each passage. The walls are wide enough so that the rat cannot prop itself up on the wall, and the walls are made out of Plexiglas, to prevent the subjects from carrying out any unwanted behavior such as climbing over the wall, or finding seams in the walls to grab onto. These mazes are filled with water because rats are typically natural swimmers, but rats prefer not to be in the water, so it provides motivation for all the subjects to want to complete the maze.[2]

This test can also be run in the dark if the researcher wants to have a greater focus on the subject's egocentric navigational abilities because if the rat cannot reference visual cues in the distance, it can not use the other type of reference based navigation, allocentric navigation. There are two parts of egocentric navigation that are evaluated, route-based navigation, a clearly defined path through an environment. The other part is path integrated navigation, the ability to take a different and more direct path to a starting location than the outbound path. Egocentric navigation is evaluated by observing the subjects and recording how many times the subject crosses a predetermined line at each T-intersection with their head and forepaws, indicating they are going in the wrong direction, or in other words, they are lost.[2]

History

The predecessor to the Cincinnati Water Maze (CWM), the Biel Water Maze (BWM), was invented in 1940 by W. C. Biel to test rats’ egocentric navigational capabilities. As such, the BWM was enclosed within a container to prevent any external stimuli, such as light, from assisting the subject in completing the task. This ensures that the rat's memory from previous trials is the primary source of information. Moreover, the original design of the BWM had walls measuring just over a fifth of a meter in height, leaving approximately 20 cm of clearance between the top of the maze and the ceiling of the container. The design of the BWM was made so that each intersection formed a T-intersection.[2]

Nevertheless, there were several concerns with the BWM, including the abundance of T-Intersections, which prompted the innovation that would result in the creation of the CWM. In contrast to the BWM, the CWM possesses wider channels to prevent larger rats from propping themselves up, and has the added benefit of asymmetry and extra intersections. Furthermore, the strategy that was predominantly seen in the BWM, where rats would swim in a straight line until forced to turn, was undone by the inherent asymmetry of the CWM. Instead, if the rats began at point-A, to arrive at point-B they would have to turn halfway down a corridor prior to reaching a dead end. Conversely, beginning at point-B towards point-A allows for the standard method previously mentioned.[2]

Uses

The Cincinnati Water Maze is most often used to measure the escape latency, which is the time required for the subject to escape the maze. Researchers may also measure the number of errors the subject makes, which are counted when the subject moves into dead ends. The animal will typically be put in the same maze for multiple trials per day with the goal being to assess the rat's procedural learning. The subject must learn the maze because it is unable to simply follow a random path, as with a standard maze. By studying the escape latency of the animal, researchers have a standardized test for the rate of learning in a subject.[2] CWMs are especially useful because they are a direct test of egocentric learning/navigation.[3] Without external visual cues, the mouse is forced to remember their movement in previous trials to escape. This is useful for determining the effect of drugs on short-term memory creation, or egocentric learning as previously mentioned. The test is also useful in mapping areas of the brain where spatial learning occurs by recording areas of brain activity during the test. In one variation, adding light, or other visual cues, researchers may measure allocentric learning/memory. With this procedure, the test becomes similar to the Morris Water Maze, where spatial learning is tested. Furthermore, in this variation, the rat is able to use both allocentric and egocentric cues to escape. This is particularly useful for studying spatial memory, as the mouse is able to use both types of navigational cues.[4]

Analysis

Weaknesses

Since water mazes have been used mostly with rats and mice, the extrapolation of research data from these experiments to other organisms and humans is limited. The Cincinnati Water Maze (CWM) poses some weaknesses to experimenters as it includes more variables that must be accounted for when drawing conclusions of the rat's cognitive behavior. For example, the element of water brings in a different stimulus than that which is present in simple grounded mazes. As such, the baseline behavioral characteristic of the rat must be noted prior to conducting a trial within this maze, as the rat's behavior outside the maze will differ from the behavior displayed when it is forced to swim within the maze. Additionally, previous research has shown that the CWM has a steeper learning curve compared to its Morris Water Maze counterpart; making the initial data collected less useful.[5][6]

Comparison to other mazes

- Original T-mazes are very simple grounded mazes (dry) that present the rat with two options to choose from.

- Allows the experimenter to make deductions of the cognitive decision making abilities of the rats as well as look for patterns in the influence one decision will have on the other.

- Multiple T-mazes help extrapolate the findings associated with right and wrong decision making, as many two choice decisions must be made consecutively to complete this kind of maze.[3]

- Very similar to the T-maze, original Y-maze is a grounded maze with a simple two choice decision to be made.

- Cognitive decision making abilities the focus of the maze, similar to T-maze.

- Y shape of maze has shown greater learning inclination, due to more gradual turns into choice options (Y shape instead of T).[3]

- Originally a grounded maze where the rat is positioned in the center of the maze and is surrounded by multiple pathways that lead to dead ends but may contain a reward.

- Short-term memory is the main factor being examined in observing the rats. As well as their response to being rewarded by choosing certain paths.

- The rat may be timed to see how long it takes to visit all the pathways; noting repeat visits to paths.[3]

- Rat is placed in water, rats are known to be very good swimmers so they can remain in water for long period of time. Rat must traverse from a starting platform to a second underwater platform placed randomly in the pool.

- Rats do not prefer water so reaction of rat to being in water is an important variable to note in observing the rats decision making.

- Rat has lots of free range in executing this maze. Holistic behavior of rat, due to less strictly placed external cues, is more easily examined.

- Drugs may be given to the rat to examine behavior in water and effect on motivation.

- Hidden platform forces rat to rely on a greater degree of its other senses in conjunction of one another. The use of which may not be as pronounced in more simple, grounded mazes.

- From this maze, one can observe if the rat is able to identify the correct location of the other platform by water ripple patterns, or other external cues.[3][7]

The Cincinnati Water Maze (CWM) can be summarized as a combination of the mazes discussed above. The mice are faced with a much different challenge when compared to a simple T or Y-maze due to the addition of more intersections, and having to navigate the maze while swimming in water. The CWM can be run in the dark and can be altered during every run the rat takes through the maze. This promotes a greater sense of urgency from the rat and allows the experimenter to get a better look at the limitations and application of the rats senses as the rat is met with extreme circumstances.[7]

Each of the mazes centered on cognitive research are measured by observing the subject's ability to maneuver through the maze whether this be measured by time, number of trials ran for the subject to choose the correct path, or number of times an undesirable outcome is achieved compared to the “desired” one in one run. Consistency from rat to rat in their ability to solve the maze task is important and allows scientists to then look for what may cause a deviation in performance in a certain rat, or groups of rats.[7]

References

- Schenk, Francoise (2013-01-11). "5: The Morris Water Maze (is not a maze)". In Foreman, Nigel; Gillett, Raphael (eds.). Handbook Of Spatial Research Paradigms And Methodologies. Psychology Press. ISBN 9781135816674.

- Vorhees, Charles V.; Williams, Michael T. (2016). "Cincinnati water maze: A review of the development, methods, and evidence as a test of egocentric learning and memory". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 57: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2016.08.002. PMC 5056837. PMID 27545092.

- Braun, Amanda; Amos-Kroohs, Robyn; Gutierrez, Arnold; Seroogy, Kim (Feb 2015). "Dopamine depletion in either the dorsomedial or dorsolateral striatum impairs egocentric Cincinnati water maze performance while sparing allocentric Morris water maze learning". Neurobiology of Learning and Memory. 118: 55–63. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2014.10.009. PMC 4331240. PMID 25451306. ProQuest 1655707843.

- Arias, Natalia; Mendez, Marta; Arias, Jorge (2014). "Brain networks underlying navigation in the Cincinnati water maze with external and internal cues". Neuroscience Letters. 576: 68–72. doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2014.05.064. PMID 24915295. S2CID 207139483.

- Vorhees, Charles V.; Williams, Michael T. (1 January 2014). "Assessing Spatial Learning and Memory in Rodents". ILAR Journal. 55 (2): 310–332. doi:10.1093/ilar/ilu013. PMC 4240437. PMID 25225309.

- Vorhees, Charles (2016). "Cincinnati water maze: A review of the development, methods, and evidence as a test of egocentric learning and memory". Neurotoxicology and Teratology. 57: 1–19. doi:10.1016/j.ntt.2016.08.002. PMC 5056837. PMID 27545092.

- Hanson, Anne. "Rats and Mazes". www.ratbehavior.org. Hanson, Anne F. and Manuel Berdoy. 2010. Rats. In: Valarie V. Tynes (ed.), Behavior of Exotic Pets. pp. 104 - 116. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Retrieved 8 April 2017.