Circassian nationalism

Circassian nationalism[1] is the desire among Circassians to reestablish an independent Circassian state in Circassia, which lost its independence in the Russian–Circassian War. Many of its themes involve the repatriation of diaspora Circassians and the revitalization of the Adyghe language.

._Turkey_in_Asia%252C_Transcaucasia._1861_(BA).jpg.webp)

Historical context

Circassia and the Circassians before the Russian invasion

The Circassians were known to inhabit their homeland since antiquity.[2] They formed many states throughout time that were known to the outside world, occasionally falling under brief control of the Romans, and later Scythian and Sarmatian groups, followed by Turkic groups including importantly the Khazars and being a protectorate of the Ottoman Empire. Nonetheless, the Circassians generally maintained a high level of autonomy. Due to their Black Sea coast location, owning the important ports of Anapa, Sochi and Tuapse, they were heavily involved in trade, and many early European slaves were Circassians (additionally, the Mamluks of Egypt, the Persian ghulams, and the Ottoman Janissaries had a strong ethnic Circassian component).

Ruling themselves, Circassians have interchangeably used feudal systems, tribal-based confederacies and monarchies to rule their lands, often incorporating a mix of two or all three. Circassia was generally organized by tribe, with each tribe having a set territory, roughly functioning as greater than a province, but less than completely autonomous, more on the level of a US state (of course, the level of autonomy varied between tribes and time). Not all of the tribes within the confederation were ethnic Circassian: at different times, Nogais, Ossetians, Balkars, Karachays, Ingush, and even Chechens participated as members of the confederation. In the 19th century, three such tribes (first one, then seeing its example, two more very close in time to each other) overthrew their feudal governments in favor of direct democracy (which some intellectuals, such as Tony Wood, argue the default government for the Chechens, at that time a neighboring polity);[3][4] however, this experiment was cut short by the conquering of Circassia by Tsarist Russia and the end of independence in favor of the rule of colonial Russia.

Circassophilia in the West

During and after the Enlightenment, Western European cultures showed much interest in the Circassians, specifically their physical appearance, language and culture, portraying the men as especially courageous (a legend that became especially popular in the court of London during the Crimean War when they were allies with Circassia). Circassians were often thought of as being especially beautiful, having curly black hair, light eyes and pale white skin (generally somewhat close to their actual appearance), giving rise to the phenomenon of Circassian beauties.[5]

The Italian and Greek presence in port towns had an effect on both the dialects of the said Italians/Greeks and the Circassians around the area (as well as the Abkhazians, if they are to be considered Circassian). The Circassian language(s) were widely regarded as unique and beautiful by 19th century linguists (today, they are often linked to extinct languages in Anatolia).

Racial scientists, after discovering an intimate similarity between the skull shapes of Caucasians (primarily judged by Circassians, Georgians and Chechens, the most numerous groups), went to declare that Europeans, North Africans, Middle Eastern peoples and Caucasians were of a common race, termed "Caucasian", or later, as it is known today, as "Caucasoid". Scientific racism went far to emphasize the superior beauty of the Caucasian people, above all the Circassians, referring to them as "how God intended the Caucasian race to be" and that the Caucasus was the "first outpost of the superior race".[6] According to Johann Freidrich Blumenbach, a chief advocate of the Circassophilic theory of Circassians as the prime and most superior examples of Caucasoid race (usually followed then by Georgians in second place), the Circassians were the closest to God's original model of humanity, and thus "the purest and most beautiful whites were the Circassians".[7]

...It is no exaggeration to say that for several decades in the middle of the 19th century "Circassia" became a household in many parts of Europe and North America. Correspondents from major newspapers found their way to Circassia or gleaned information from foreign consuls and merchants in Trebizond and Constantinople. The "Circassian question", the political status of the northwestern highlands of the Caucasus, was debated in parliaments and gentlemen's clubs.[8]

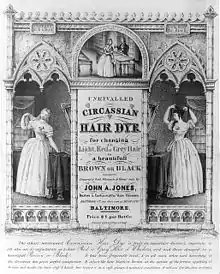

Meanwhile, beauty products got names in the US and Western Europe such as "Circassian Soap", "Circassian Curl", "Circassian Lotion",[9] "Circassian Hair Dye",[10][11] "Circassian Eye Water",[12] etc. The Circassian is also known to be, somewhat correctly, tall and thin. This admiration developed for the Circassians, especially their physique, but also (later) their culture, which in some ways resembled that of Medieval Europe, such as the feudal system employed by some tribes.

Though Circassophilia already was a fad in the West, it took a suddenly different form during the Crimean War, when the alliance with the Circassians of Britain led to a more understanding, even sympathetic view of them: rather than a simple obsession with their physical characteristics; expressions of solidarity with the "beautiful, honorable Circassians" became a sort of war rally. Britain glumly observed the Muhajirs (Caucasian exiles) miserably, only to forget that the Circassians ever existed decades later once their country had been absorbed by Russia. This had a profound effect on modern nationalism, as noted by Charles King.[13]

Russian invasion, conflict and Muhajirism

The earliest date of Russian expansion into Circassian land was in the 16th century, under Ivan the Terrible, who notably married a Kabardin wife Maria Temryukovna, the daughter of Muslim prince Temryuk of Kabardia to seal a contract of alliance with the Kabardins, a subdivision of the Circassians. After Ivan's death, however, Russian interest in the Caucasus subsided and they remained largely removed from its affairs; with other states in between Russia and Circassia, notably the Crimean Khanate and the Nogai Horde.[14] The Circassians freely roamed in their native regions for centuries afterwards, but during the peaks of the Persian Safavids and Afsharids, parts of the Circassian lands fell under Persian rule for a brief number of years.

In the 18th century, however, Russia regained its imperial ambitions in the region, and expanded steadily southward, with the eventual goal of obtaining the riches of the Middle East and Persia, using the Caucasus as a connection to the region.[15] The first incursion of the Russian military into Circassia occurred in 1763, as part of the Russo-Persian War.

Eventually, due to a perceived need for Circassian ports and a view that an independent Circassia would impede their plans to extend into the Middle East (plans which were never achieved), Russia soon moved to annex Circassia. Tensions culminated in the devastating Russian-Circassian War, which in its later stages was eclipsed by the Crimean War. Despite the fact that a similar war was going on at the other side of the Caucasus (Chechnya, Ingushetia, and Dagestan fighting against Russia to preserve their states' existence), as well as the attempts of some (ranging from Circassian princes to Imam Shamil to Britain) to connect the two struggles, connections between the Circassians and their allies with their Eastern Caucasian counterparts were quashed by an Ossetian alliance with Russia.

Hostilities peaked in the 19th century, and led directly to the Russian-Circassian War, in which the Circassians, along with the Abkhaz, Ubykhs, Abazins, Nogais, Chechens and in the later stages the Ingush (who started out as allies of Russia), as well as a number of Turkic tribes, fought the Russians to maintain their independence. This conflict became entangled with the ensuing Crimean War, and at various times the Ottomans gave small assistance to the Circassian side. Additionally, the Circassians succeeded in securing the sympathies of London, and in the later stages of the Crimean War, the British supplied arms and intelligence to the Circassians, who reciprocated by busying the Russians and returning with intelligence of their own. However, this was not enough to save the Circassians from the oncoming defeat and Russian domination. Russia finally subdued the Circassians, tribe after tribe, with the Ubykhs, Abazins, Abkhaz and Balkars being last. While some tribes accepted Russian rule after being firmly conquered, others continued insurgency, even though Circassia as a whole had surrendered.

Russia soon proceeded to order the Muhajirs. Approximately 1-1.5 million Circassians were killed, and upon order of the Tsar, and most of the Muslim population was deported (i.e., all except Ossete Muslims and Kabardins; the modern Circassians and Abazins either managed to escape or, as is the case with most, returned; at the time after the deportation, as Charles King notes in his books, travelers who searched throughout the area for Circassians could not find any left except the Kabardins), mainly to the Ottoman Empire, causing the exile of another 1.5 million Circassians and others. This effectively annihilated (or deported) 90% of the nation.[16] Circassians refugees were viewed as an expedient source for military recruits,[17] and were settled in restive areas of nationalist yearnings- Armenia, the Kurdish regions, the Arab regions and the Balkans.[18] The Balkan and Middle Eastern societies they settled among considered them foreign aliens, and tensions between the Circassians and the natives over land and resources occasionally led to bloodletting, with the impoverished Circassians sometimes raiding the natives.[19] At the Conference of European Countries which was held in December 1876 – January 1877 in Istanbul, the idea of transferring the Circassians from the Balkans to the Asian states of the empire was introduced. With the beginning of the Russian-Ottoman War in 1877, Circassians abandoned their villages and set on the road with the retreating Ottoman troops.[20] Still more Circassians were forcefully assimilated by nationalist Muslim states (Turkey, Iran, Syria, Iraq, etc.) who looked upon non-Turk/Persian/Arab ethnicity as a foreign presence and a threat.

In modern times

Emergence of the modern movement

The modern movement has its roots in secret societies as well as organizations during the perestroika period under Mikhail Gorbachev.

Support

Circassian nationalism is becoming increasingly popular among younger Circassians, and to a lesser extent, older ones as well.[21] It is now almost universally popular among younger Circassians, causing fears for the Russian government (especially as now the Circassians' neighbors, such as the Balkars/Karachay, have adopted similar agendas).[1] It is suspected by some analysts that even the republican governments have members with nationalistic agendas.[22]

Modern Circassian nationalism is the ideology of several activist groups in the so-called "Circassian belt" of autonomous republics in Russia, as well as in areas where the Circassian diaspora is (Turkey, Israel, etc.), and in Abkhazia, which has ethnic ties to Circassia.

The widely criticized 1999 election in Karachay–Cherkessia where the Cherkes candidate was beaten became a symbol of martyrdom, causing huge crowds of Abazins and Circassians in the capital to lead protests.[22]

Both Adyge Khase and the International Circassian Organization have declared that their aim is "to protect the rights of the Circassians wherever they live and to facilitate the return of the substantial portion of the Circassian Diaspora to the Circassian inhabited lands of the Northwest Caucasus to change the demographic structure" (back to what it was before ethnic cleansing occurred) [23]

Attempting to achieve recognition of the "Circassian genocide" is also a very prominent movement among Circassians, though it is not necessarily purely nationalist. Another major movement, often tied into this, but more blatantly nationalistic, is the movement to recreate a "historical Circassia", the core of Circassian nationalism, with its historical territories, and make Circassian one group on the census. There is a feeling among some Circassians that the notion that Kabardins, Adyghe, Cherkes and Shapsugs (all four are separate on the Russian census) are different nations is a Kremlin strategy designed to divide the Circassian nation. Many politicians even warn that if this is not removed, that "dismemberment will ultimately lead to the death of the Circassian nation".[24] Many Circassian nationalists (moderates, such as Cherkesov)[25] do not advocate withdrawing from the Russian federation, holding instead that a unified Circassia still within Russia is good enough.[26] Nonetheless, most assert that this unified Circassia within Russia should have one official language, Adyghe.

The movement to split Karachay–Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria has won itself the official support of many Circassians (especially in Karachay–Cherkessia, where Karachay and Russians dominate government posts) as well as the influential Circassian organization "Adyge Khase".[23]

After the crisis involving the ethnic identity of the man who first scaled Mt.Elbrus, a group of young Circassians, led by Aslan Zhukov, reconquered the mountain in a symbolic move. Aslan Zhukov (also 36-year-old founder of Adyge Djegu, another major Circassian nationalist organization) was then murdered on 14 March 2010 by a gunshot in a dark alley.[27][28][29] His death spurred another round of rioting among Circassians, who variously attribute his death to the government of the republic, the Russian government, the Russians in the republic or the Karachay, some combination, or all four. The head of the republic said that his death should not be painted in ethnic terms but this only resulted in the addition of him to the list of possible culprits from the Circassian point of view.

Adygea

In Adygea, a number of reports came in August 2009 about Russian Orthodox crosses being thrown off mountains in symbolic demonstrations against the Russian Orthodox church, viewed by Circassians as a symbol of oppression.[30]

The perceived favoritism of Moscow towards the Cossacks is also a major bone of contention amongst Circassians.[31]

An organization calling itself "Union of Slavs", led by Nina Konovaleva and Boris Karatayev, was created in 1991 to counter the activities of Circassian organizations such as Adyge Khase, and prevent Circassians from removing Russians from positions of prestige and power, as well as to "protect Russians/Cossacks from Circassian control of the land".[23] In 1991, Union of Slavs in Adygeya actively opposed the establishment of Adygeya as separate from Krasnodar Krai as an ethnic republic within Russia, stating that Circassians were only 22% of the populace and as such, it was not fair to the other 78%. The Union of Slavs has called the increasing autonomy of Adygeya and the activism in Karachay–Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria part of a "dangerous conspiracy" to create a "Greater Circassia", achieve demographic dominance by repatriating Diaspora Circassians, and then marginalize or even expel the Russian residents ("colonists", in Circassian ideology).[23][32] It has called for the liquidation of the three Circassian republics (two of which are also shared with Karachays or Balkars) due to "discrimination of Russians".[23][33]

In Karachayevo-Cherkessia

In November 2009, in response to a fallacious news article deemed to slander the nation, Circassian activists ramped up efforts with the scheduling of a mass-protest against the ignorance of the Russian government and the Russian people of their rights in Karachaevo-Cherkessia.[34] However, the government canceled the gathering, saying it would be banning any and all public gatherings for an indefinite period to prevent the spread of the H1N1 flu virus.[34][35] However, the head of the Circassian youth movement, Timur Jujuev, said "All the public markets continue working on a regular basis, so where is the emergency? We are going to organize the demonstration even if we will need to wear surgical masks and even if we do not have a license from the government. This is not the will of one or two men; it is the will of a nation, and we have right to say what we think".[34][36]

There has also been a swift escalation of tension between the Circassians and the non-Circassians in the three republics (Russians, Karachai and Balkars). While the Russians in Adygea demand the abolition of Adygea, the Karachai have taken to a strategy of keeping Circassians out of office- Jamestown reports that "Over the last seven months, the Karachai majority in the KCHR parliament have repeatedly banned the Circassian candidate Vyacheslav Derev from taking a position in the Russian Federation Council" (the time of reporting was November 2009).[34][37] Furthermore, for the last 31 years, no Circassian has held the highest post in the republic, as the Soviet and then Russian officials always appointed Karachai.

There is a movement, highly popular among both Circassians and Karachai, to divide the republic into monoethnic units of Cherkessia and Karacheia, perhaps to prepare these units for a merger.[38]

There have also been numerous clashes between Karachai and Circassian historians over various historical issues. One of the most scandalous cases occurred when Karachai historians claimed that the conqueror of Mt. Elbrus (Khashar Chilar in Circassian, Hilar Hakirov in Karachai) was a Karachai rather than a Circassian from Nal'chik (going against the testimony of the members of the early 19th century expedition to the top of the mountain which he led).[34] On 20 November, a poster hailing the "great Karachai hero" Hakilov in Cherkessk was burned and destroyed by unknown perpetrators.[34][39]

What actually started the protests by Circassians in Karachaevo-Cherkessia was a news article by the local newspaper Express-Post.[34] It denied the fact that the Circassian village of Besleney had saved dozens of Jewish children from the Nazis, prompting a joint Jewish-Circassian contingent to protest the existence of the report as well as an outcry in Circassian-operated independent media sources.[40] Express-Post apologized later, but it was these protests that were planned to be spread to the capital (and canceled) to protest the general "deep oppression" of Circassians.[34][35]

In Kabardino-Balkaria

Intended to coincide with protests in Karachay–Cherkessia, Circassian youth groups held mass "national protests" in Kabardino-Balkaria on 17 November 2009. It was attended by about 3000 people (considering that it was limited to the city of Nal'chik and the small population of the republic's Circassian population alone, let alone in that city, this is a huge figure).[34] Ibragim Yagan, a leader of a Circassian NGO posted a video on Facebook. It featured him standing under both the flag of the Russian Federation and the Circassian national flag, called upon all Circassian youth to wake up to claim their rights and historic lands. He said that "We have been constantly watched, followed, blackmailed for our political activities... But we cannot lose anymore, because we have already lost everything." Yagan is then drowned out by a wave of cheers.

It is important to note that unlike in Adygea (22% Circassian as of 2003) and Karachay–Cherkessia (11-16%, depending on if the Abazins are considered Circassian, in 2003), Kabardino-Balkaria has a clear Circassian (of the Kabardin subdivision) majority (at 55%). However, "after the parliament of KBR ratified the bill ‘On land and territory’ earlier this month, each Balkar living in KBR in turn has received 10.6 hectares of the land while only 1.6 hectares belong to each Circassian" [34] noted Jelyabi Kalmykov, and this soon became a rallying cry at the protest.[41] Ruslan Keshev, the leader of the Circassian Congress in Kabardino-Balkaria declared that "If the government does not listen to us we are ready for radical actions. This is the only homeland we have."[34]

Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia

The Russian recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia is also an issue. On one hand, Circassians are often highly enthusiastic to help the Abkhaz, who they view as brothers, and are enthusiastic also for Abkhazia's independence.[42] On the other hand, however, it evidences a perceived double standard used negatively on the Chechens (whom many Circassians supported during the First Chechen War), and to a lesser extent, the Circassians as well.[43][44] Paul A. Goble noted that the recognition of South Ossetia, in addition to enraging the Chechens and Ingush, also radicalized many Circassians against Russia, because of the mass of double standards.[45]

There is a large amount of cooperation between Circassian activists and Abkhazia as well: Circassians poured into Abkhazia to assist them in their war for independence against Georgia, and most websites dedicated to independence of Circassia or promotion of Abkhazia are linked to their cross-Caucasus counterpart. According to Western Circassophile John Colarusso, some Circassians consider Abkhazia a possible addition to Circassia if the Abkhaz themselves wish to join.

Repatriation

Repatriation has been a major issue. The Russian state (as well as Russians in general), as noted above, is highly suspicious of any return of the Circassians (not in the least because it was Russia who exiled them in the first place for "security reasons"), while Circassians living in Circassia view it as the only way to revive the nation and save it from extinction.

The Circassians have set up a number of organizations with the explicit goal of encouraging return of their "brothers". The most notable of these is the ICA (International Circassian Association)'s "Repatriation Committee", which has branches in several countries.

Russia has a double digit official repatriation quota for Circassians viewed by many (Colarusso, Henze, etc.) as being an attempt to prevent the Circassians, who are viewed as a threat, from returning.

On 9 August 2009, Adygea officially attempted to overrule the Russian immigration quota for Circassians by putting forth its own de facto quota, which was drastically higher, allowing many more Circassians to return to their homeland.[46] According to Western Circassophile John Colarusso, the movement to allow and encourage Circassian return to their homeland (hence, changing the demographics in a way that is advantageous for the Circassians and disadvantageous for the Russians) is one of the major objectives and rallying points of the modern movement.[47][48]

Russia has also unintentionally (in addition to the single-digit quota for Circassians, which is defined as including all four of the census groups as well as the Abazins) set up a number of barriers. According to an essay by Cicek Chek, these include:

Circassians living in the North Caucasus and the more numerous Circassians living in the Diaspora have been seeking a radical simplification of the procedures for the repatriation of the community. Most Circassians who have tried to return have fallen under the provisions of the 1991 Russian citizenship law which requires that:

- they give up their previous citizenship,

- live in the country for five years before getting Russian citizenship

- know Russian, and pass a test on the Russian Constitution,

- keep a large sum in a bank of the republic that they try to acquire the citizenship from, and

- people holding non-ordinary passports (diplomatic, privileged, etc) could not apply at all.

The situation has further deteriorated as a result of the adoption in 2003 of the Russian law on the legal status of foreign citizens living in the Russian Federation. That measure makes it even more difficult for Circassians from the Diaspora to return. Despite official statements from Moscow favoring increased repatriation, the current repatriation regime has been a complete failure by any measure.[49]

Additionally, many Circassians in the diaspora opt not to return for additional reasons of inconvenience, losing job and economic well-being, losing contact with friends, etc.

There have been numerous instances of murders of returnee Circassians by ethnic Russians living in both Krasnodar and Adygea.

It has been reported that the fact that Russia's repatriation policies have shown heavy favoritism to ethnic Russians and have granted very few if any Circassians the right to return is another major grievance, especially considering that the return of Circassians to Russia would aid Russia in its attempts to overcome its crisis of declining population.[50]

Diaspora renaissance

In the first decade of the 21st century, the Circassian diaspora abroad has begun experiencing a cultural reawakening. Contacts are being established with their homeland, but also, more importantly, there are now many institutions being founded to strengthen the Circassian identity within the diaspora. For example, in 2005, the Circassian Education Foundation (website here: ), a scholarship fund for Circassians, was founded in Wayne, New Jersey, USA. It is, in fact, a creation of a mother-organization, the Circassian Benevolent Organization. It has since given scholarship funds to Circassians across the US. The organization (Circassian Education Foundation) has also worked on a project of making a free online Circassian-American English dictionary (available here: which will then, it hopes, be used by Circassians for their language so they can, in turn pass it on to their children as well as revitalize it.

The Circassian diaspora in the Middle East also are undergoing a cultural reawakening, largely due to the reestablishment of contacts with their homeland, however, unlike that in Western countries (primarily the US, Germany, The Netherlands, Austria and Israel), it is often paired with tension between Circassians and the ethnic majority of the country, Arabs or Turks.[51] The governments of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, Russia and Iran have all forced assimilation of Circassians and suppressed their culture in the past and suppressed various attempts at past renaissances.[52] Nonetheless, in the past few years, in many of these countries, the diaspora has become much more aware of their identity and active. "Nart-TV", a program broadcasting from Adygeya, about Circassian identity, history and life, is now broadcasting in many Middle Eastern countries, including Israel and Jordan.[53]

On 8 August 2010, a university opened in Amman, Jordan, specifically for Circassians to preserve Circassian heritage and culture, with classes in the Circassian language and on Circassian culture and history in addition to practical topics.[54]

Russian reaction

Russians may view Circassian nationalism extremely fearfully and suspiciously, not simply because it claims a chunk of what Moscow considers its territory, but because, just as was the case with Chechnya, the Baltics, and so on, nationalist movements may result in the loss of the previous prestige and dominance by ethnic Russians, a stigmatization of the Russian language, and the re-establishment of native dominance (hence, the "South Africa" syndrome).[23]

As a result of tensions, politics in all three republics are often highly ethnic-based, and in Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay–Cherkessia, the dispute is often three-way (Russians vs. Circassians and Abazins vs. Karachay in Karachay–Cherkessia; Russians vs. Kabardins vs. Balkars in Kabardino-Balkaria).

While Kabardino-Balkaria and Karachay–Cherkessia's non-Circassian leaders have come under fire from Circassian nationalists for "oppression", ethnic Adyge leader Aslan Dzharimov of Adygea styled himself as a moderate who would balance the centralizing urges of Moscow and the Russians against the autonomism/separatism of the Adyge.[55] Although originally popular on this premise, he soon ended up angering both sides, and Adyge Khase denounced him as a collaborationist and "traitor to the Circassian nation".

Russians may often view the three republics as integral parts of Russia, especially since Russians are an overwhelming majority of the resident population in Adygea.

The Russian government has taken to either trying to silence the nationalism or trying to gain control over individual Circassian activist groups.[56] Analysts, even Russians such as Sergei Markedonov [57] have voiced concern over what they perceive as the continuing "radicalization" of Circassian youth due to the Kremlin's attempts to control them, and are disappointed that Medvedev continues this policy.[58]

In addition, Russia officially keeps a very low immigration quota for Circassians - as low as 50 (though the only republics Circassians would likely to immigrate to are those in former Circassia). The government of Adygea, however, has seized the opportunity to override this quota for their own territory with their own version: 1400 per year for Adygea alone (rather than 50 per year for all of Russia).[46][59] After Russian protest at this action, Adygea said that they were in fact acting on Yeltsin's own words – for republics to "take as much sovereignty as they can swallow".[60]

Russia has criticized [61][62] articles in the constitutions of the three republics discussing heritage, language and the like and labeling them as "separatist", recommending they be edited.

Some websites, such as CircassianWorld[63] have published various articles of stories from Circassian activists about them (the activists) being intimidated by "FSB veterans", as the activists claim they identified themselves.

Russia has denounced several of the assertions that the Adygei have of their history (in addition to Ukrainian accounts of Holodomor and Chechen and other accounts of the perceivedly genocidal deportation to Siberia) - including the genocide - as false and "fabrications", and as attempts to throw tar on Russia's reputation.[64]

The Cossacks, even more than other Russians, are highly antagonistic towards Circassian nationalism, as it is towards their aims, which include the revival of traditional Cossack paramilitary forces, already underway in Russia (see Cossacks and related pages). Circassians believe that will be a tool, as the Cossacks were in the past, for oppression of ethnic minorities and silencing their demands.[23][65]

Many journalists, both Circassian and Russian (for example, Natalya Rykova[66]), have stated that Russian "skinheads" are intrinsically tied to the ethnic tensions in the "Circassian" republics, whose opinions they perceive as being advanced not in the least by the Russian media.[67] According to the above-cited article from Window-On-Eurasia, "Polls show that many Russians believe the problem of hate crimes can be solved either by restricting immigration or by toughening law enforcement", and that "...Confronted with this challenge, the Russian government has largely failed to do what is necessary to contain it. It "liquidated" a special ministry for nationality affairs. It closed the federal program for promoting tolerance and countering extremism. And it fails to provide sufficient funds and staff to other ministries to deal with the challenge." Furthermore, Putin's current policy for internal division of the Russian Federation is not at all pleasing for advocates of self-determination: it advocates "enlargement of regions of Russia".[68] Sergei Mironov stated on 30 March 2002 that "89 federation subjects is too much, but larger regional units are easier to manage" and that the goal was to merge them into 7 federal districts. Gradually, over time, ethnic republics were to be abolished to accomplish this goal of integration.[68][69]

Many people, ranging from Circassian activist coordinators to Akhmed Zakayev, Ichkerian head of government-in-exile to the liberal journalist Fatima Tlisova have speculated that Russia has tried to use a policy of divide and rule throughout the North Caucasus (citing examples of the Circassian vs. Karachai/Balkar rivalry, Ossetian-Ingush conflict, Georgian-Abkhaz conflict, Georgian-Ossetian conflict, interethnic rivalries in Dagestan and even the first Nagorno-Karabakh War, which Russia also insists on mediating), creating "unnatural conflicts" that can only be solved by Kremlin intervention, keeping Caucasian peoples both weak and dependent on Russia to mediate their conflicts.[34] Sufian Jemukhov and Alexei Bekshokov, leaders of the "Circassian Sports Initiative" stated that the conflict "has the potential to blow up the whole Caucasus into a bloody mess with the mass civilian casualties and therefore keep the Circassians from opposing the Sochi Winter Olympics...Moscow plays the conflict scenario when the participants do not have the ability to solve the conflict, but the conflict is absolutely manageable and can be easily solved by its rulers from the Kremlin."[34][70]

In the context of the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics

The occurrence and location of the Sochi Olympics are particularly inflaming, and even insulting, to Circassians. They will take place at the site of one of the largest post Russo-Circassian war massacres of Circassians, and on the official anniversary of Circassian Genocide.[71] As a result, it has become a rallying point to the Circassian activist organizations.

Campaign for genocide recognition

Former Russian President Boris Yeltsin's 1994 made a statement acknowledging “resistance to the tsarist forces [in the 19th century] was legitimate,” but he stopped short of recognizing “the guilt of the tsarist government for the genocide.”

A few years later, the leaders of Kabardino-Balkaria and Adygea sent appeals to the Duma, asking it “to reconsider the situation and to issue the needed apology.”

In the later years of the 2000-2010 decade, the movement to secure recognition for the Circassian genocide, largely taking a leaf out of the book of the Armenians has gained in momentum and popularity.[72] Reasons for this include the location of the Sochi Olympics, US recognition of the Armenian genocide (prompting a bill on the Circassian genocide in New Jersey, where most Circassians in the US live) and the repeated insistence by Russians that the Georgians committed "genocide" against the Abkhaz and Ossetes.[73]

In October 2006, the Circassian organizations operating in Russia, Turkey, Israel, Jordan and several other countries with well-sized diasporas sent the president of the European Parliament a letter with a request to recognize the genocide against the Circassian people. There has been no action taken so far.

Circassians have attempted to attract global media attention to the Circassian Genocide and its relation to the city of Sochi (where the Olympics were held in 2014) by holding mass protests in Vancouver, Istanbul and New York during the 2010 Vancouver Winter Olympics.[74]

On 20 March 2010, a Circassian Genocide Congress was held in the Georgian capital of Tbilisi, funded in part by the Circassian members of the Western political analysis center, the Jamestown Federation.[75][76]

The congress passed a resolution, urging Georgia to become the first UN-recognized State to recognize the Circassian Genocide.[76] In May 2011, Georgia followed through and recognized the acts as a genocide.[77][78][79] Soon after, the Chechen separatist government-in-exile announced that it commended Georgia's decision, and advocated pan-Caucasian solidarity,[80] and Circassians, Georgians, Chechens and other Caucasian diaspora in European countries staged demonstrations to show their support.[81][82][83] In appreciation for the Georgian recognition, the Georgian flag was seen flying in Nalchik, the capital of Kabardino-Balkaria, which had been a bastion of anti-Georgian sentiment before the recognition.[50]

See also

References

- Fatima Tlisova. "Support for Circassian Nationalism Grows in the North Caucasus". Georgiandaily.net, through Adyga NatPress.

- Smeets, Rieks (1995). "Circassia" (PDF). Central Asian Survey. p. 108.

- The Chechen Nation: A Portrait of Ethnical Features Lyoma Usmanov Jan, 9, 1999, Washington, D.C.

- K. Tumanov was the first to pay attention to the existence of Chechens in ancient times in East Asia and Southern Caucasus. ("The prehistoric language of Caucasus", Tiflis, 1913).

- see King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus

- "The Circassian Beauty Archive". The Lost Museum. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Winthrop, Jordan (1968). White over Black. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. pp. 222–3.

- King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford, 2010. Page 93.

- . Morning Chronicle (NYC). 20 September 1806. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Barrett, Thomas M. "Southern Living (in Captivity): The Caucasus in Russian Popular Culture". The Journal of Popular Culture. 31 (4): 75–93. doi:10.1111/j.0022-3840.1998.3104_75.x.

- "Bloom of Circassia". New York Gazette. 2 September 1782.

- . Delaware Gazette and State Journal. 2 February 1815. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - King, Charles. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. Oxford, 2010. Pages 92-123.

- See Charles King's The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus

- Wood, Tony. Chechnya: the Case for Independence.

- "145th Anniversary of the Circassian Genocide and the Sochi Olympics Issue". Reuters. 22 May 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Glenny, Misha. The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers.

The Porte...used the influx as refugees as an expedient and declared that that the new soldiers should be recruited from the Circassians

- Charles King. The Ghost of Freedom: A History of the Caucasus. p. 97.

Part of the Ottomon resettlement strategy was to place Circassians in areas where either Muslim or Turkic populations were low...Circassian families were sent to Syria, the Balkans, and eastern Anatolia and resettled amid restive communities of Arabs, Slavs, Kurds and Armenians.

- King, The Ghost of Freedom, pages 97-98.

- "Syrian Circassians". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Youth Activists Unravel Kremlin Status-Quo in the Circassian Heartland: "The Wind of Freedom is Approaching!"". North Caucasus Analysis Volume: 10 Issue: 15. The Jamestown Foundation. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- http://www.iwpr.net/?p=p&s=f&o=159562&apc_state=hENf-159565

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Goble, Paul (14 September 2009). "Circassian Youth Seek 'Radical' Renewal of National Movement". Window on Eurasia. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Bella Ksalova (22 January 2010). ""Adyge Khasse": idea of united Circassia is no threat to Russia's integrity". Caucasian Knot. Archived from the original on 30 March 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Paul Goble (25 January 2010). "United Circassia Said No Threat To Russia but Divided could be". Window On Eurasia. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- "Murder of Circassian Activist Unsettles Multi-Ethnic Karachaevo-Cherkessia". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Caucasian Knot - Friends of assassinated Aslan Zhukov hold protest action in Karachai-Circassia". Caucasian Knot. Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 6 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "The Role of the Russian Orthodox Church in the North Caucasus". Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 162. The Jamestown Foundation. 21 August 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Fatima Tlisova (1 August 2008). "Moscow's Favoritism Towards Cossacks Mocks Circassian History". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- "What is there in the ICA’s Dossier” published in the Russian Language bulletin of the Union Of Slavs, Za Kubanye in Adygeya in its October 2000 edition, No: 21

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 7 February 2011. Retrieved 5 April 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Fatima Tlisova (25 November 2009). "Circassians in Karachaevo-Cherkessia Plan Mass Protest". Eurasia Daily Monitor Volume: 6 Issue: 218. The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 2 April 2010.

- http://www.09biz.ru, 19 November

- http://www.kavkaz-uzel.ru, 19 November

- NTR local television channel, 12 November

- "In Cherkessk they still demand to divide republic into Karachai and Circassia". Adygei NatPress. 29 November 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- "Cherkessk", 21 November

- "Circassians who saved Jewish children: what are we slandered in mass-media for?". Adygea NatPress. 10 November 2009. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Gazeta Yuga, 19 November, cited in Jamestown Article (let us find this thing... and translate it)

- Paul Goble. "WindowonEurasia". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "ðòá÷äá.info - òÏÓÓÉÑ É ÞÅÒËÅÓÙ". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 20 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 19 November 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Goble, Paul (6 August 2009). "Adygeya, Ignoring Moscow, Boosts Repatriation Quotas for Circassians". Circassian World. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- The World & I, November 1991 issue. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Times Publishing Corporation. Pp. 656-669. [translated into Circassian, Russian, Turkish, and Arabic]

- http://www.circassianworld.com/new/diaspora/1443-circassian-repatriation-by-cicek-chek.html

- Valery Dzutsev (23 May 2011). "Georgia's Increasingly Assertive North Caucasus Policy Is Likely to Cause Waves Across the Region". Jamestown Foundation.

- Colarusso, John. Circassian Repatriation: When Culture is Stronger than Politics. The World & I, November 1991 issue. Washington, D.C.: The Washington Times Publishing Corporation. Pp. 656-669. [translated into Circassian, Russian, Turkish, and Arabic] -- available here: Archived 8 December 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 16 June 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "В Иордании началась трансляция фильмов об Адыгее In Jordan, began airing movies on Adygea" (in Russian). Adygea NatPress. 3 January 2010. Retrieved 6 May 2010.

- Hana Namrouqa (8 August 2010). "New academy to promote Circassian language, traditions". The Amman Times.

- Aslan Dzharimov, Ozerklikten Cumhuriyete Adigey (From Autonomy to Republic: Adygeya), in Turkish, Turkiye Isbirligi ve Kalkinma Ajansi, 1996, Ankara/Turkey, page 16.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 28 November 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Ñåâåðîêàâêàçñêèé ðåãèîí ðàññìàòðèâàåòñÿ ãëàâîé ãîñóäàðñòâà âíå îáùåðîññèéñêîãî êîíòåêñòà - Ãàçåòà.Ru - Êîììåíòàðèè". Ãàçåòà.Ru. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Paul Goble. "WindowonEurasia". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Репатриация на Кавказ: "принцип Ельцина"? (in Russian). Information Portal "Adygi.RU". 5 August 2009. Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 8 August 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.natpress.net/stat_e.php?id=4513%5B%5D

- "Moscow Excises "Separatist" Articles from Constitutions of Circassian Republics". The Jamestown Foundation. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Aslan Idar (15 February 2007). "THE FSB'S CAMPAIGN TO ERADICATE CIRCASSIAN NATIONALISM". Chechnya Weekly. The Jamestown Foundation. Archived from the original on 20 May 2009. Retrieved 14 October 2009.

- Fatima Tlisova (27 January 2010). "Moscow Uses Commission on "Historical Falsification" to Deny Circassian Rights". NatPress.Net.

- Valery Tishkov, Ethnicity, Nationalism and Conflict In And After The Soviet Union: The Mind Aflame, Sage Publications, London, Thousand Oaks, New Delhi, 1997, page 236.

- "Кто остановит российских скинхедов?". РИА Новости. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Paul Goble. "WindowonEurasia". Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- "Enlargement of Russian regions will take place all the same". English pravda.ru. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

- Anastasia Matveeva, Maxim Momot (2 April 2010). "Journal of RBC: The Kremlin once again pondered the enlargement of regions". Adygea NatPress. Retrieved 6 April 2010. (English Translation)

- Adygey Natpress, 14 November... let's find this... (my Russian is little more than nonexistent)

- Zhemukhov, Sufian (September 2009). "The Circassian Dimension of the 2014 Sochi Olympics". PONARS Policy Memo No. 65 - Georgetown University. Circassian World. Archived from the original on 11 October 2009. Retrieved 28 November 2009.

- Radio Adiga (28 March 2010). "Public of Adygeya consider it necessary to recognize the Circassian genocide". Caucasian Knot, through Adygea NatPress. Retrieved 7 March 2010.

- Ali Kasht (1 April 2010). "Circassians between Georgia and Abkhazia:Sorry, the Circassians are not stupid". Adygea NatPress. Archived from the original on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Murat Temirov (3 January 2010). "Fire and Ash Olympics". Adyghe Heku. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- Ferris-Rotman, Amie (21 March 2010). "Russian Olympics clouded by 19th century deaths". Reuters, through Yahoo!News. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- Dzutsev, Valery (25 March 2010). "Circassians Look to Georgia for International Support". Jamestown. Archived from the original on 13 February 2016. Retrieved 5 April 2010.

- Georgia Says Russia Committed Genocide in 19th Century. The New York Times. 20 May 2011

- Georgia Recognizes ‘Circassian Genocide’ Archived 18 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Civil Georgia. 20 May 2011

- Recognizes Russian 'Genocide' Of Ethnic Circassians. Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. 20 May 2011

- Usman Ferzauli, The Minister for Foreign Affairs ChRI (23 May 2011). "chechencenter.info/n/breaking-news/34-breaking-news/1361-1.html". Chechen Center, Chechen Republic of Ichkeria Press Release. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- "Chechens support Circassians". ChechenCenter.info. 23 May 2011. Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

- "Circassians in Turkey mark anniversary of alleged genocide". Hurriyet Daily News. 22 May 2011.

- Andrea Alexander (20 May 2011). "North Jersey Circassians to mark genocide anniversary". NorthJersey.com.

External links

- Circassian World – A website celebrating Circassian culture and nation. It has extensive news reporting and coverage of issues, maps of historical Circassia, as well as essays by historians, linguists, etc., and tracks of popular modern Circassian music

- The Circassian Education Foundation, a scholarship fund organization for Circassian children, which also works on an online dictionary for Circassian to English

- Video on YouTube showing historical Circassia with its tribal divisions, speaking briefly about the desire for a free nation. Movie made by a Circassian.

- Video on YouTube, this one discussing the belief among Circassian scholars about links to the Ancient Hatti in Anatolia, also backed by some linguists. Video from nationalist website www.circassiantv.net. In Adyghe (Circassian) language)

- Aliy Berzegov (5 June 2008). "Teofil Lapinski: Hero and Leader of the Circassian War for Independence (Part One)". North Caucasus Analysis. 9 (22).

- Aliy Berzegov (12 June 2008). "Teofil Lapinski: Hero and Leader of the Circassian War for Independence (Part Two)". North Caucasus Analysis. 9 (23).

- T. Tatlok (1958). "The Ubykhs". Caucasian Review. 7. Munich. pp. 100–109.

- Stephen D. Shenfield (1999). "The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide?". In Mark Levene and Penny Roberts (ed.). The Massacre in History. www.berghahnbooks.com. Oxford and New York: Berghahn Books.

- Cicek Chek (27 February 2010). "Circassian Repatriation". Circassian World.com.

- Sufian Zhemukhov (December 2008). "The Circassian World: Responses to New Challenges". Circassian World.com. Archived from the original on 12 October 2009. Retrieved 6 March 2010.

- Zeynel A. Besleney (21 May 2010). "Circassian Nationalism and the Internet". openDemocracy and Circassian World. Retrieved 18 November 2010.