Clarendon Shopping Centre

The Clarendon Centre (or Clarendon Shopping Centre[1]) is a shopping centre in central Oxford, England, opened in 1984. The centre faces Cornmarket Street, and has other entrances onto Queen Street and Shoe Lane. The fascia onto Cornmarket Street is that of the Woolworths store which had, in a decision later criticised, replaced the Georgian Clarendon Hotel; it was discovered during demolition that medieval construction had been present within the hotel. The shopping centre was expanded in 2012–14. Major tenants include TK Maxx, H&M and Gap Outlet.

%252C_September_2019.jpg.webp) The entrance from Cornmarket Street, in the former Woolworths store | |

| |

| Location | Oxford, England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°45′09″N 01°15′31″W |

| Opening date | 1984 (refurbished c.1998; expanded 2012–14) |

| Developer | Arrowcroft |

| Owner | Lothbury Investment Management Limited |

| Architect | Gordon Benoy and Partners |

| No. of stores and services | 23 |

| Total retail floor area | 13,500 m2 (145,000 sq ft) |

| Website | www |

Location

The centre is in central Oxford,[2] located to the west of Cornmarket Street and to the north of Queen Street. It is accessible from both of these streets and is L-shaped. There is also an entrance on Shoe Lane, off New Inn Hall Street. On the opposite side of Cornmarket is the more historic Golden Cross shopping arcade, located in the medieval courtyard of one of the coaching inns of Oxford, leading to the Covered Market. At the western end of Queen Street is the Westgate Shopping Centre, which was extensively redeveloped and extended in 2017.[3]

History

Site history

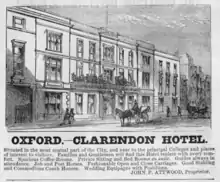

On this site was the Clarendon Hotel on Cornmarket Street, which grew from two former coaching inns, the King's Head and the Star.[4] The hotel was a Georgian building,[5] though beneath it was a vaulted wine cellar,[6] which was the oldest in Oxford.[7] The hotel closed in 1939;[8] Woolworths purchased it in that year; it was used as an American Servicemen's Club, and then as offices, before being demolished in 1954.[4] The demolition was later criticised.[8]

The area was the site of an early archaeological study in the 1950s.[9] Architectural excavations, by W. A. Pantin and E. M. Jope, took place during and after the demolition.[5][6] During these, it was discovered that the wine cellar dated back to the twelfth century, and the "complete framework of a sixteenth century timber-framed house" was behind the fascia, among other architectural discoveries.[5] Pantin made the argument that, had this been known before demolition, the building could have been saved:[5]

Outwardly, the Clarendon seemed just a pleasant but rather undistinguished late Georgian building, so that it could be argued at the time of the discussions and inquiry about its demolition that it was not a building of historic or artistic importance. […] If only we had known a few years ago what we now know about the Clarendon, we could have put forward a much better case and a much better scheme for at least its partial preservation and adaptation.

The dig also revealed wares dating back to Saxon Britain, including eleventh-century pottery and a thirteenth-century aquamanile.[9]

The new Woolworths branch was designed by Sir William Holford, who sought to build a "Woolworths worthy of Oxford" after previous designs were rejected; Holford's design was also rejected by Oxford City Council, but the decision was overturned by Harold Macmillan,[10] who was the Minister of Housing and Local Government at the time.[8] The store was ceremonially opened on 18 October 1957 by the Mayor and Mayoress of Oxford; the former complimented the building. The branch was five times larger than its predecessor[4]—indeed, when it opened, it was the biggest in Europe[11]—and contained a deluxe cafeteria, offices, a roof garden and a multi-storey car park.[10][12] While the store was open, the ceremony of "beating the bounds" of the parish of St Michael at the North Gate required the participants to pass through the store.[11] The store closed in 1983.[10][12]

Development as a shopping centre

The Clarendon Centre was built on the site in 1983–84,[2] designed by Gordon Benoy and Partners, and built by property company Arrowcroft.[13] The centre was financed by the pension fund of the National Westminster Bank. It initially had 11,800 square metres (127,000 sq ft) of retail space, with Littlewoods as a 4,600-square-metre (50,000 sq ft) anchor store. There were more than 20 other shops,[14] with shops signed up prior to construction including Dolcis, Etam, Chelsea Girl and Dixons.[13] The centre was developed in two phases, with the first being the section connecting Cornmarket Street to Shoe Lane.[14]

The frontage of the old building on Cornmarket Street was retained,[12] including the ornate "W" mark above a door.[10] For the frontage onto Queen Street, the former Halfords shop was demolished;[15] Halfords would later open within the centre, in a unit facing Shoe Lane.[16] In January 1984, one person was killed and another seriously injured when a collapse occurred at the Queen Street demolition site for the centre.[15]

The centre was completed in 1984,[4] being already fully let in October of that year, before it was completed.[14] Writing in the "Oxford Diary" column in The Times in January 1984, A. N. Wilson labelled the newly built centre as "the most grotesquely horrible building I have ever seen";[17] in 1985, a reporter for The Observer described the centre's "phoney unfunctional pipes" and Bavarian marble floors.[18]

In 1998, as the first step of a renovation of the centre, the Littlewoods store gave up 930 square metres (10,000 sq ft) of space adjacent to Cornmarket Street, to create space for a new store;[19] this was later filled by Gap, after the landlord, Gartmore Group, wanting to make the centre more fashion-focused, rejected a larger bid from the electronics retailer Comet.[20] Following the £5m renovation (which also involved new lighting and doors, and redecoration), the centre (now described as having 14,000 square metres (150,000 sq ft) of retail space) was sold to an investment partnership in July 2000, for £80m. H Samuel and French Connection were other new stores following the renovation.[21]

The centre's layout was slightly modified in 2001, when the former Etam and Halfords units were merged to accommodate a relocated and enlarged Dixons store.[16] Then, on Saturday 7 August 2004, Littlewoods, the original anchor tenant, closed, notice of the closure having been given on the preceding Tuesday; contemporary reports suggested the closure was due to financial underperformance and another retailer's interest in the unit.[22] The unit was subsequently taken by Zara, on a fifteen-year lease.[23]

2010s changes

%252C_September_2019.jpg.webp)

In 2012, a plan was put forward to extend the centre floorspace by 10%: replacing the section near Shoe Lane with a three-storey extension, to house H&M.[24] Prior to construction of the extension, archaeologists carried out an excavation beneath the site to discover remains of occupation from the 17th century and earlier.[25] The new H&M store opened in 2014.[26]

Following the reopening of Westgate Oxford in October 2017, the branch of Zara within the centre moved to the Westgate, vacating its unit in the Clarendon.[27] The site was taken over by TK Maxx, who opened their store on 30 May 2019, to queues of shoppers.[28] The conversion of the store retained the stone in a stockroom marking the boundary of the parish of St Michael at the North Gate, which is supposedly the oldest of the boundary stones; the ceremony to mark the boundary still passes through the centre.[29]

Stores

The centre has twenty-three stores and food outlets as of November 2019, including those opening soon. These include TK Maxx, H&M and Gap Outlet.[30] In total the centre has 13,500 square metres (145,000 sq ft) of space.[31]

References

- "Shopping Centre at Clarendon Shopping Centre". www.visitoxfordandoxfordshire.com. Visit Oxfordshire. Archived from the original on 18 October 2012. Retrieved 19 August 2012.

- Hibbert, Christopher, ed. (1988). "Clarendon Centre". The Encyclopaedia of Oxford. Macmillan. p. 94. ISBN 0-333-39917-X.

- Google (7 September 2019). "Clarendon Centre, Oxford" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Jenkins, Stephanie. "52 Cornmarket Street (site of former Star/Clarendon Hotel)". Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Pantin, W. A. (1958). "The Clarendon Hotel, Oxford: Part II. The Buildings" (PDF). Oxoniensia. XXIII: 84–129. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Jope, E. M. (1958). "The Clarendon Hotel, Oxford: Part I. The Site" (PDF). Oxoniensia. XXIII: 1–83. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 August 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Sherwood, Jennifer; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1974). Oxfordshire. The Buildings of England. Penguin Books/Yale University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-300-09639-2.

- Chipperfield, John (12 April 2010). "Oxford hotel's facade hid its true history". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Hassall, Tom (1987). Oxford: The Buried City. Oxford Archaeological Unit. pp. 6, 34. ISBN 0 904220 09 5.

- "Twice around the block". Woolworths Museum. Archived from the original on 8 June 2017. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Morris, James (1965). Oxford. Faber and Faber. pp. 52, 110.

- "Sabrina" (2014). "Oxford – Store 189". Woolies Buildings – Then and Now. Archived from the original on 5 July 2019. Retrieved 7 September 2019.

- Kinloch, Bruce (22 March 1983). ""Arrowcroft in £40m Oxford shops project"". The Daily Telegraph. p. 22. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Oxford centre pre-let". The Daily Telegraph. 23 October 1984. p. 17. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- ""Firm blamed in court for shop collapse"". Aberdeen Evening Express. 25 February 1985. p. 7.

- ""More jobs at Dixons"". Oxford Mail. 3 December 2001. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Wilson, A. N. (9 January 1984). "Oxford Diary: Expiring dreams". The Times. p. 8.

- Owen, Lyn (17 February 1985). "Oxford fights for its history". The Observer.

- Roberts, Jane (28 February 1998). "Pru digs deep for Oxford St". Estates Gazette. p. 46.

- Roberts, Jane (4 April 1998). "Gap wins bid war for Oxford shop". Estates Gazette. p. 41.

- "Shopping centre sold for 80m". Oxford Mail. 7 July 2000. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Retailers vie for city sites". Oxford Mail. 6 August 2004. Archived from the original on 21 September 2019. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Zara portfolio to reach 29 UK stores with new openings for Oxford and Inverness". Retail Week. 24 September 2004. Archived from the original on 30 December 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- Ffrench, Andrew (16 March 2012). "Oxford's Clarendon Centre grows to 'defend itself'". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Shoppers pop in to see what lies beneath Clarendon centre at archaeology day". Oxford Mail. 6 August 2012. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 18 October 2019.

- Ffrench, Andrew (22 December 2017). "Rival Oxford shopping centre says Westgate is boosting trade rather than stealing it". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 14 September 2018. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Ffrench, Andrew (13 February 2019). "Shops coming and going – the changing face of Oxford shopping". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 14 February 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Jones, Harrison (30 May 2019). "TK Maxx Oxford: Clarendon Centre store queues for opening". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- Clayton, Indya (31 May 2019). "Beating of the bounds still going strong in Oxford city centre". Oxford Mail. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 8 September 2019.

- "Stores". Clarendon Centre. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Lothbury Property Trust: Top 10 Assets". Lothbury Investment Management. Archived from the original on 7 November 2016. Retrieved 9 September 2019.