Clerodane diterpene

Clerodane diterpenes, sometimes referred to as clerodane diterpenoids, are a large group of secondary metabolites that have been isolated from several hundreds of different plant species, as well as fungi, bacteria and marine sponges.[1] They are bicyclic terpenes that contain 20 carbons and a decalin core.

Classification

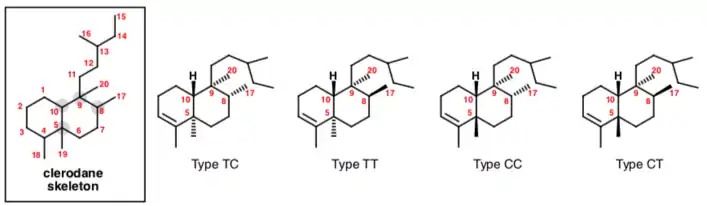

The clerodane diterpenes are classified into four groups trans-cis (TC), trans-trans (TT), cis-cis (CC), and cis-trans (TC) based on the relative stereochemistry at the decalin junction (trans or cis) and the relative stereochemistry of the substituents at C-8 and C-9 (trans or cis). The absolute stereochemistry of the clerodanes is classified as neo (shown below) or ent-neo (enantiomeric to neo). The neo-clerodanes share the same absolute stereochemistry as clerodin. Approximately 25% of clerodanes have the 5:10 cis ring junction. The remaining 75% have a trans 5:10 ring junction.[2]

Biosynthesis

They are structurally related to the bicyclic labdane diterpenes. Its biosynthesis in plants (mostly present in the families Lamiaceae and Asteraceae) takes place in the chloroplasts. Some forms can be useful intermediates in organic synthesis.[3] Some clerodanes like clerodin (3-desoxy-caryoptinol) from the leaves of Clerodendrum infortunatum (Verbenaceae) have anthelminthic properties, others like ajugarins are repellent to herbivore predators (mostly insects and their larvae) or have a very bitter taste, such as gymnocolin.

Some examples for clerodanes are ajugarins I to V extracted from bugleweeds like Ajuga remota, Ajuga ciliata, Ajuga decumbens, common skullcap (Scutellaria galericulata), and germanders (Teucrium sp.), cascarillin from Croton eluteria, calumbins from Jateorhiza columba, Jateorhiza palmata and guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia), gymnocolin from Gymnocolea inflata, hardwickiic acid from Hardwickia species (Fabaceae). Neo-clerodane diterpenes can have hallucinogenic properties such as salvinorin A, a trans-neoclerodane diterpene from Salvia divinorum.[4]

See also

References

- Li R, Morris-Natschke SL, Lee KH (October 2016). "Clerodane diterpenes: sources, structures, and biological activities". Natural Product Reports. 33 (10): 1166–226. doi:10.1039/C5NP00137D. PMC 5154363. PMID 27433555.

- Merritt AT, Ley SV (June 1992). "Clerodane diterpenoids". Natural Product Reports. 9 (3): 243–87. doi:10.1039/np9920900243. PMID 1436738.

- Arns S, Barriault L (June 2007). "Cascading pericyclic reactions: building complex carbon frameworks for natural product synthesis". Chemical Communications (22): 2211–21. doi:10.1039/b700054p. PMID 17534496.

- Shirota O, Nagamatsu K, Sekita S (December 2006). "Neo-clerodane diterpenes from the hallucinogenic sage Salvia divinorum". Journal of Natural Products. 69 (12): 1782–6. doi:10.1021/np060456f. PMID 17190459.

External links

- Clerodane+diterpenes at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)