Terpene

Terpenes (/ˈtɜːrpiːn/) are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predominantly by plants, particularly conifers.[1][2] Terpenes are further classified by the number of carbons: monoterpenes (C10), sesquiterpenes (C15), diterpenes (C20), etc. A well known monoterpene is alpha-pinene, a major component of turpentine.

Still more numerous than terpenes is a class of compounds called "terpenoids". Terpenoids are terpenes that have been modified with (usually oxygen-containing) functional groups. The terms terpenes and terpenoids are used interchangeably. Both have strong and often pleasant odors, which may protect their hosts or attract pollinators. The inventory of terpenes and terpenoids is estimated at 55,000 chemical entities.[3]

Biological function

Terpenes are also major biosynthetic building blocks. Steroids, for example, are derivatives of the triterpene squalene. Terpenes and terpenoids are also the primary constituents of the essential oils of many types of plants and flowers.[4] In plants, terpenes and terpenoids are important mediators of ecological interactions. For example, they play a role in plant defense against herbivory, disease resistance, attraction of mutualists such as pollinators, as well as potentially plant-plant communication.[5][6] They appear to play roles as antifeedants and wound repair.

Higher amounts of terpenes are released by trees in warmer weather, where they may function as a natural mechanism of cloud seeding. The clouds reflect sunlight, allowing the forest temperature to regulate.[7]

Terpenes are also used by insects as a form of defense. For example, termites of the subfamily Nasutitermitinae to ward off predatory insects, through the use of a specialized mechanism called a fontanellar gun, which ejects a resinous mixture of terpenes.[8]

Applications

The one terpene that has major applications is natural rubber (i.e. polyisoprene). The possibility that other terpenes could be used as precursors to produce synthetic polymers has been investigated as an alternative to the use of petroleum-based feedstocks. However, few of these applications have been commercialized.[9] Many other terpenes, however, have smaller scale commercial and industrial applications. For example, turpentine, a mixture of terpenes (e.g. pinene), obtained from the distillation of pine tree resin, is used an organic solvent and as a chemical feedstock (mainly for the production of other terpenoids).[10] Rosin, another by-product of conifer tree resin, is widely used as an ingredient in a variety of industrial products, such as inks, varnishes and adhesives. Terpenes are widely used as fragrances and flavors in consumer products such as perfumes, cosmetics and cleaning products, as well as food and drink products. For example, the aroma and flavor of hops comes, in part, from sesquiterpenes (mainly α-humulene and β-caryophyllene), which affect beer quality.[11]They are also components of some traditional medicines, such as aromatherapy. Some form hydroperoxides that are valued as catalysts in the production of polymers.

Reflecting their defensive role, terpenes are used as active ingredients of natural pesticides in agriculture.[12]

Physical and chemical properties

Terpenes are colorless, although impure samples are often yellow. Boiling points scale with molecular size: terpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes respectively at 110, 160, and 220 °C. Being highly non-polar, they are insoluble in water. Being hydrocarbons, they are highly flammable and have low specific gravity (float on water).

Terpenoids (mono-, sesqui-, di-, etc.) have similar physical properties but tend to be more polar and hence slightly more soluble in water and somewhat less volatile than their terpene analogues. Highly polar derivative of terpenoids are the glycosides, which are linked to sugars. They are water-soluble solids. They are tactilely light oils considerably less viscous than familiar vegetable oils like corn oil (28 cP), with viscosity ranging from 1 cP (ala water) to 6 cP. Like other hydrocarbons, they are highly flammable. Terpenes are local irritants and can cause gastrointestinal disturbances if ingested.

Terminology

The term "terpene" was coined in 1866 by the German chemist August Kekulé.[13] Although sometimes used interchangeably with "terpenes", terpenoids (or isoprenoids) are modified terpenes that contain additional functional groups, usually oxygen-containing.[14] The name "terpene" is a shortened form of "terpentine", an obsolete spelling of "turpentine".

Biosynthesis

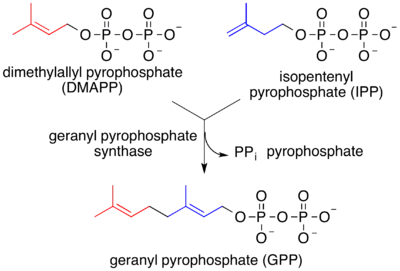

Conceptually derived from isoprenes, the structures and formulas of terpenes follow the biogenetic isoprene rule or the C5 rule, as described in 1953 by Leopold Ružička and coworkers.[15] The isoprene units are provided from isoprenyl pyrophosphate (aka dimethylallyl pyrophosphate) and isopentenyl pyrophosphate, which exist in equilibrium. This pair of building blocks are produced by two distinct metabolic pathways: the mevalonic acid pathway and the MEP/DOXP pathway.

Mevalonic acid pathway

Most organisms produce terpenes through the HMG-CoA reductase pathway, known as the Mevalonate pathway, named for the intermediates mevalonic acid. This pathway begins with acetyl CoA.

MEP/DOXP pathway

The 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate/1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate pathway (MEP/DOXP pathway), also known as non-mevalonate pathway or mevalonic acid-independent pathway, starts with pyruvate as the carbon source.

Pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate are converted by DOXP synthase (Dxs) to 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, and by DOXP reductase (Dxr, IspC) to 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP). The subsequent three reaction steps catalyzed by 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol synthase (YgbP, IspD), 4-diphosphocytidyl-2-C-methyl-D-erythritol kinase (YchB, IspE), and 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclodiphosphate synthase (YgbB, IspF) mediate the formation of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 2,4-cyclopyrophosphate (MEcPP). Finally, MEcPP is converted to (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMB-PP) by HMB-PP synthase (GcpE, IspG), and HMB-PP is converted to isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) by HMB-PP reductase (LytB, IspH).

IPP and DMAPP are the end-products in either pathway, and are the precursors of isoprene, monoterpenoids (10-carbon), diterpenoids (20-carbon), carotenoids (40-carbon), chlorophylls, and plastoquinone-9 (45-carbon). Synthesis of all higher terpenoids proceeds via formation of geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP).

The MVA and MEP are mutually exclusive in most organisms.

| Organism | Pathways |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | MVA or MEP |

| Archaea | MVA |

| Green Algae | MEP |

| Plants | MVA and MEP |

| Animals | MVA |

| Fungi | MVA |

Geranyl pyrophosphate phase and beyond

In both MVA and MEP pathways, IPP is isomerized to DMAPP by the enzyme isopentenyl pyrophosphate isomerase. IPP and DMAPP condense to give geranyl pyrophosphate, the precursor to monoterpenes and monoterpenoids.

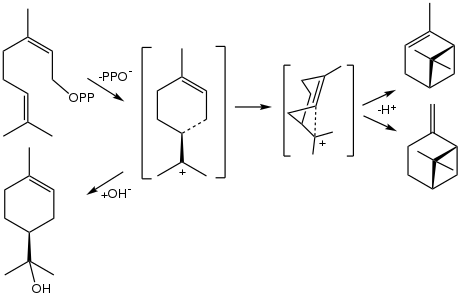

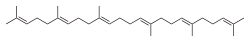

Geranyl pyrophosphate is also converted to farnesyl pyrophosphate and geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate, respectively C15 and C20 precursors to sesquiterpenes and diterpenes (as well as sesequiterpenoids and diterpenoids).[2] Biosynthesis is mediated by terpene synthase.[16][17]

Terpenes to terpenoids

The genomes of 17 plant species contain genes that encode terpenoid synthase enzymes imparting terpenes with their basic structure, and cytochrome P450s that modify this basic structure.[2][18]

Structure

Terpenes can be visualized as the result of linking isoprene (C5H8) units "head to tail" to form chains and rings.[19] A few terpenes are linked “tail to tail”, and larger branched terpenes may be linked “tail to mid”. These are called “irregular” terpenes.

- Formula

Strictly speaking all monoterpenes have the same chemical formula C10H16. Similarly all sequiterpenes and diterpenes are respectively C15H24 and C20H32. The structural diversity of mono-, sesqui-, and diterpenes is a consequence of isomerism.

- Chirality

Terpenes and terpenoids are usually chiral. Chiral compounds can exist as non-superimposable mirror images, which exhibit distinct properties (odor, toxicity, etc.).

- Unsaturation

Most terpenes and terpenoids feature C=C groups, i.e. they exhibit unsaturation. Since they carry no functional groups aside from their unsaturation, terpenes are structurally distinctive. The unsaturation is associated with di- and trisubstituted alkenes. Di- and trisubstituted alkenes resist polymerization (low ceiling temperatures) but are susceptible to acid-induced carbocation formation.

Classification

- Selected terpenes

Limonene, a monoterpene.

Limonene, a monoterpene. Carvone is a monoterpenoid, a modified monoterpene.

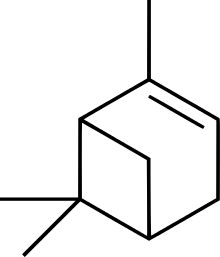

Carvone is a monoterpenoid, a modified monoterpene. Pinene, a monoterpene which exists as two isomers, is a major consistituent of turpentine.

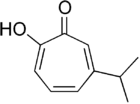

Pinene, a monoterpene which exists as two isomers, is a major consistituent of turpentine. Hinokitiol is a monoterpenoid, a tropolone derivative.

Hinokitiol is a monoterpenoid, a tropolone derivative.

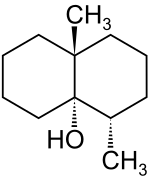

Geosmin is a sesquiterpenoid.

Geosmin is a sesquiterpenoid.

Terpenes may be classified by the number of isoprene units in the molecule; a prefix in the name indicates the number of isoprene pairs needed to assemble the molecule. Commonly, terpenes contain 2, 3, 4 or 6 isoprene units; the tetraterpenes (8 isoprene units) form a separate class of compounds called carotenoids; the others are rare. The classification is formalistic only; nothing may be inferred about their properties, uses or occurrence.

- Hemiterpenes consist of a single isoprene unit. Isoprene itself is considered the only hemiterpene, but oxygen-containing derivatives such as prenol and isovaleric acid are hemiterpenoids.

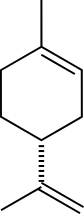

- Monoterpenes consist of two isoprene units and have the molecular formula C10H16. Examples of monoterpenes and monoterpenoids include geraniol, terpineol (present in lilacs), limonene (present in citrus fruits), myrcene (present in hops), linalool (present in lavender), hinokitiol (present in cypress trees) or pinene (present in pine trees).[20][21] Iridoids derive from monoterpenes. Examples of iridoids include aucubin and catalpol.

- Sesquiterpenes consist of three isoprene units and have the molecular formula C15H24. Examples of sesquiterpenes and sesquiterpenoids include humulene, farnesenes, farnesol, geosmin.[21] (The sesqui- prefix means one and a half.)

- Diterpenes are composed of four isoprene units and have the molecular formula C20H32. They derive from geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate. Examples of diterpenes and diterpenoids are cafestol, kahweol, cembrene and taxadiene (precursor of taxol). Diterpenes also form the basis for biologically important compounds such as retinol, retinal, and phytol.

- Sesterterpenes, terpenes having 25 carbons and five isoprene units, are rare relative to the other sizes. (The sester- prefix means two and a half.) An example of a sesterterpenoid is geranylfarnesol.

- Triterpenes consist of six isoprene units and have the molecular formula C30H48. The linear triterpene squalene, the major constituent of shark liver oil, is derived from the reductive coupling of two molecules of farnesyl pyrophosphate. Squalene is then processed biosynthetically to generate either lanosterol or cycloartenol, the structural precursors to all the steroids.

- Sesquarterpenes are composed of seven isoprene units and have the molecular formula C35H56. Sesquarterpenes are typically microbial in their origin. Examples of sesquarterpenoids are ferrugicadiol and tetraprenylcurcumene.

- Tetraterpenes contain eight isoprene units and have the molecular formula C40H64. Biologically important tetraterpenoids include the acyclic lycopene, the monocyclic gamma-carotene, and the bicyclic alpha- and beta-carotenes.

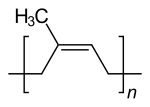

- Polyterpenes consist of long chains of many isoprene units. Natural rubber consists of polyisoprene in which the double bonds are cis. Some plants produce a polyisoprene with trans double bonds, known as gutta-percha.

- Norisoprenoids, such as the C13-norisoprenoid 3-oxo-α-ionol present in Muscat of Alexandria leaves and 7,8-dihydroionone derivatives, such as megastigmane-3,9-diol and 3-oxo-7,8-dihydro-α-ionol found in Shiraz leaves (both grapes in the species Vitis vinifera)[22] or wine[23][24] (responsible for some of the spice notes in Chardonnay), can be produced by fungal peroxidases[25] or glycosidases.[26]

Industrial syntheses

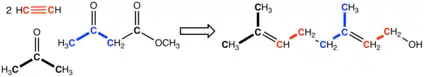

While terpenes and terpenoids occur widely, their extraction from natural sources is often problematic. Consequently, they are produced by chemical synthesis, usually from petrochemicals. In one route, acetone and acetylene are condensed to give 2-Methylbut-3-yn-2-ol, which is extended with acetoacetic ester to give geranyl alcohol. Others are prepared from those terpenes and terpenoids that are readily isolated in quantity, say from the paper and tall oil industries. For example, α-pinene, which is readily obtainable from natural sources, is converted to citronellal and camphor. Citronellal is also converted to rose oxide and menthol.[1]

References

- Eberhard Breitmaier (2006). Terpenes: Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheromones. Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527609949. ISBN 9783527609949.

- Davis, Edward M.; Croteau, Rodney (2000). "Cyclization enzymes in the biosynthesis of monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes, and diterpenes". Biosynthesis. Topics in Current Chemistry. 209. pp. 53–95. doi:10.1007/3-540-48146-X_2. ISBN 978-3-540-66573-1.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Chen, Ke; Baran, Phil S. (June 2009). "Total synthesis of eudesmane terpenes by site-selective C–H oxidations". Nature. 459 (7248): 824–828. doi:10.1038/nature08043.

- Omar, Jone; Olivares, Maitane; Alonso, Ibone; Vallejo, Asier; Aizpurua-Olaizola, Oier; Etxebarria, Nestor (April 2016). "Quantitative Analysis of Bioactive Compounds from Aromatic Plants by Means of Dynamic Headspace Extraction and Multiple Headspace Extraction-Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry: Quantitative analysis of bioactive compounds…". Journal of Food Science. 81 (4): C867–C873. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.13257. PMID 26925555.

- Martin, D. M.; Gershenzon, J.; Bohlmann, J. (July 2003). "Induction of Volatile Terpene Biosynthesis and Diurnal Emission by Methyl Jasmonate in Foliage of Norway Spruce". Plant Physiology. 132 (3): 1586–1599. doi:10.1104/pp.103.021196. PMC 167096. PMID 12857838.

- Pichersky, E. (10 February 2006). "Biosynthesis of Plant Volatiles: Nature's Diversity and Ingenuity". Science. 311 (5762): 808–811. Bibcode:2006Sci...311..808P. doi:10.1126/science.1118510. PMC 2861909. PMID 16469917.

- Adam, David (October 31, 2008). "Scientists discover cloud-thickening chemicals in trees that could offer a new weapon in the fight against global warming". The Guardian.

- Nutting, W. L.; Blum, M. S.; Fales, H. M. (1974). "Behavior of the North American Termite, Tenuirostritermes tenuirostris, with Special Reference to the Soldier Frontal Gland Secretion, Its Chemical Composition, and Use in Defense". Psyche. 81 (1): 167–177. doi:10.1155/1974/13854. Retrieved 22 July 2011.

- Silvestre, Armando J.D.; Gandini, Alessandro (2008). "Terpenes: Major Sources, Properties and Applications". Monomers, Polymers and Composites from Renewable Resources. pp. 17–38. doi:10.1016/B978-0-08-045316-3.00002-8. ISBN 9780080453163.

- Eggersdorfer, Manfred (2000). "Terpenes". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a26_205.

- Steenackers, B.; De Cooman, L.; De Vos, D. (2015). "Chemical transformations of characteristic hop secondary metabolites in relation to beer properties and the brewing process: A review". Food Chemistry. 172: 742–756. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.139. PMID 25442616.

- Isman, M. B. (2000). "Plant essential oils for pest and disease management". Crop Protection. 19 (8–10): 603–608. doi:10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00079-X.

- Kekulé coined the term "terpene" to denote all hydrocarbons having the empirical formula C10H16, of which camphene was one. Previously, many hydrocarbons having the empirical formula C10H16 had been called "camphene", but many other hydrocarbons of the same composition had had different names. Hence Kekulé coined the term "terpene" in order to reduce the confusion.

See:

- Kekulé, August (1866). Lehrbuch der organischen Chemie [Textbook of Organic Chemistry] (in German). vol. 2. Erlangen, (Germany): Ferdinand Enke. pp. 464–465. From pp. 464–465: "Mit dem Namen Terpene bezeichnen wir … unter verschiedenen Namen aufgeführt werden." (By the name "terpene" we designate in general the hydrocarbons composed according to the [empirical] formula C10H16 (see §. 1540). Many chemists subsume the hydrocarbons of the formula C10H16 under the general name "camphene". That name seems unsuitable, because a specific substance of this group has been designated as "camphene". In general, a great confusion prevails in the designation of substances belonging here [i.e., to the terpene group]. Many, obviously different hydrocarbons have not been distinguished for a long time and have been assigned the same names, while on the other hand, probably identical substances from different sources have often been specified by different names.)

- Dev, Sukh (1989). "Chapter 8. Isoprenoids: 8.1. Terpenoids.". In Rowe, John W. (ed.). Natural Products of Woody Plants: Chemicals Extraneous to the Lignocellulosic Cell Wall. Berlin and Heidelberg, Germany: Springer-Verlag. pp. 691–807. ; see p. 691.

- "IUPAC Gold Book - terpenoids".

- Eschenmoser, Albert; Arigoni, Duilio (December 2005). "Revisited after 50 Years: The 'Stereochemical Interpretation of the Biogenetic Isoprene Rule for the Triterpenes'". Helvetica Chimica Acta. 88 (12): 3011–3050. doi:10.1002/hlca.200590245.

- Kumari, I.; Ahmed, M.; Akhter, Y. (2017). "Evolution of catalytic microenvironment governs substrate and product diversity in trichodiene synthase and other terpene fold enzymes". Biochimie. 144: 9–20. doi:10.1016/j.biochi.2017.10.003. PMID 29017925.

- Pazouki, L.; Niinemets, Ü. (2016). "Multi-Substrate Terpene Synthases: Their Occurrence and Physiological Significance". Frontiers in Plant Science. 7: 1019. doi:10.3389/fpls.2016.01019. PMC 4940680. PMID 27462341.

- Boutanaev, A. M.; Moses, T.; Zi, J.; Nelson, D. R.; Mugford, S. T.; Peters, R. J.; Osbourn, A. (2015). "Investigation of terpene diversification across multiple sequenced plant genomes". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (1): E81–E88. Bibcode:2015PNAS..112E..81B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419547112. PMC 4291660. PMID 25502595.

- Ružička, Leopold (1953). "The isoprene rule and the Biogenesis of terpenic compounds". Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 9 (10): 357–367. doi:10.1007/BF02167631. PMID 13116962. S2CID 44195550.

- Breitmaier, Eberhard (2006). Terpenes: Flavors, Fragrances, Pharmaca, Pheromones. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–13. ISBN 978-3527317868.

- Ludwiczuk, A.; Skalicka-Woźniak, K.; Georgiev, M.I. (2017). "Terpenoids". Pharmacognosy: 233–266. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-802104-0.00011-1.

- Günata, Z.; Wirth, J. L.; Guo, W.; Baumes, R. L. (2001). Carotenoid-Derived Aroma Compounds; chapter 13: Norisoprenoid Aglycon Composition of Leaves and Grape Berries from Muscat of Alexandria and Shiraz Cultivars. ACS Symposium Series. 802. pp. 255–261. doi:10.1021/bk-2002-0802.ch018. ISBN 978-0-8412-3729-2.

- Winterhalter, P.; Sefton, M. A.; Williams, P. J. (1990). "Volatile C13-Norisoprenoid Compounds in Riesling Wine Are Generated From Multiple Precursors". American Journal of Enology and Viticulture. 41 (4): 277–283.

- Vinholes, J.; Coimbra, M. A.; Rocha, S. M. (2009). "Rapid tool for assessment of C13 norisoprenoids in wines". Journal of Chromatography A. 1216 (47): 8398–8403. doi:10.1016/j.chroma.2009.09.061. PMID 19828152.

- Zelena, K.; Hardebusch, B.; Hülsdau, B.; Berger, R. G.; Zorn, H. (2009). "Generation of Norisoprenoid Flavors from Carotenoids by Fungal Peroxidases". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 57 (21): 9951–9955. doi:10.1021/jf901438m. PMID 19817422.

- Cabaroğlu, T.; Selli, S.; Canbaş, A.; Lepoutre, J.-P.; Günata, Z. (2003). "Wine flavor enhancement through the use of exogenous fungal glycosidases". Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 33 (5): 581–587. doi:10.1016/S0141-0229(03)00179-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terpenes. |

- Institute of Chemistry - terpenes

- Structures of alpha pinene and beta pinene

- Terpenes at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Pope, Frank George (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 647–652. This contains a detailed survey of the chemistry of many terpenes, which had recently been investigated fully.