Clover Hill Tavern

The Clover Hill Tavern with its guest house and slave quarters are structures within the Appomattox Court House National Historical Park.[3] They were registered in the National Park Service's database of Official Structures on October 15, 1966.[4]

Clover Hill Tavern | |

Clover Hill Tavern | |

| |

| Location | Appomattox County, Virginia |

|---|---|

| Nearest city | Appomattox, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 37°22′40.8″N 78°47′45.6″W |

| Built | 1819 |

| Visitation | 102,397 (2019)[1] |

| Part of | Appomattox Court House National Historical Park (ID66000827[2]) |

| Added to NRHP | October 15, 1966 |

The tavern was built by two brothers as a stagecoach stop for the line they started in 1809 between Richmond and Lynchburg, Virginia. They had bought a farm at Clover Hill which was halfway between these town. It came with a small building that served as headquarters for their enterprise. This was expanded into a tavern and a guest house inn for travelers. It was a popular rest stop and prospered, eventually turning into a village.

History

The tavern originally opened in 1819 on the Richmond-Lynchburg Road for travelers and is the oldest original structure in the village of Appomattox Court House, with the exception of the Sweeney Prizery outside of the local of the village but within the Park.[5] It became a popular rest stop and over-night lodging for the stagecoach travelers.[6] The Clover Hill Tavern inn grew and farmhouses grew up around it soon after it opened. It was built by Alexander Patteson and his brother Lilburne Patteson as a stagecoach stop for the line between Cumberland County and Lynchburg.[4] The Patteson brothers formed a partnership in 1809 to develop a stagecoach line between Richmond, Virginia, and Lynchburg. They purchased the farm acreage of Clover Hill in 1814, which was about halfway between these towns.[7] The land came with an existing small frame dwelling which they used as the headquarters for their stagecoach business.[8]

There was much optimism after the War of 1812. The brothers made considerable money since there was a good economic boom starting in 1815. Clover Hill developed into a thriving commercial village with many people passing through into the "frontier states", such as Kentucky, Tennessee, and Indiana. Lilburne died in 1816. In 1819, Alexander built a 2 1⁄2-story, four-bay structure as his main residence for his large family. This also served as a tavern. Patteson also built a three-story tavern guest house to go with the tavern. The residence became the Clover Hill Tavern with the guest house converted into an additional dining room and additional guest rooms.[8]

The tavern was the residence of Captain John Raine and his wife Eliza in the 1840s. In 1839, the Raines purchased half interest in the tavern and the accompanying 206 acres (0.83 km2) for $1,525 from the estate of Alexander Patteson, who died in 1836. In 1840, they purchased the other half interest of the property for the same price from the estate of Lilburne Patteson. The stagecoach was stopping twice every day at the tavern during the week and once during the weekend. In spite of this, through poor management of running the tavern business, he ultimately had to sell the property to his brother Hugh in 1842 for the balance of the overdue notes on the property. The 1840 U.S. Census of Prince Edward County shows the Raine family consisted of 10 children, seven boys and three girls.[7]

In 1845, when Appomattox County was established, a post office was formed and the original "court house" was built along with law offices and other government-related businesses. The village of "Clover Hill" changed its name to "Appomattox Court House". In 1846, Samuel D. McDearmon bought the Clover Hill Tavern. The village had approximately 150 people throughout the 1850s.[7]

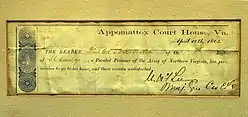

In 1865, on Palm Sunday, the rapidly approaching end of the Civil War changed the prosperity of the Clover Hill Tavern with the surrender of General Robert E. Lee to General Ulysses S. Grant. The Generals arranged a meeting to be held in town at the McLean House so Lee could formally surrender his troops to Grant, effectively ending the American Civil War. Approximately thirty thousand paroles for the Confederate soldiers were printed in the Clover Hill Tavern.[9]

At the time of General Lee's surrender to Union commander Grant in 1865 the Tavern and its associated outbuildings were owned by Wilson Hix. Billy Hix, Wilson's son, was the sheriff of the village of Appomattox Court House then. Brigadier General George H. Sharpe, as head of the Bureau of Military Information and Assistant Provost Marshal, made the Clover Hill Tavern his headquarters starting on April 10, 1865. Sharpe was designated by Grant to oversee the printing of parole passes which were issued to the Confederate veterans. Research by historians of the Park reveal that perhaps the paroles were printed in the wooden dining room wing at the west end of the Tavern that no longer is there.[5] The paroles allowed the surrendered Confederate soldiers to travel unmolested to their homes.[9]

The Clover Hill village ("Appomattox Court House") of the 1850s consisted of the Clover Hill Tavern, the Old Appomattox Court House, two blacksmith shops, the original county jail, the Jones and Woodson law offices, the Plunkett-Meeks Store, two stables, the McLean and Peers homes and some cabins.[8]

A National Park Service marker at the front entrance of the Clover Hill Tavern reads:[10]

Built in 1819, this was the first building in what would become the village of Appomattox Court House. The Clover Hill Tavern served travelers along the Richmond-Lynchburg Stage Road. For several decades, it offered the village’s only restaurant, only overnight lodging, and only bar. Its presence helped prompt the Virginia legislature to locate the Appomattox County seat here. In 1846, the courthouse was built across the street.

By 1865, the tavern had come on hard times – a "bare and cheerless place", according to one Union general. It was one of only two buildings in town used by the Federal army during the surrender process. Here, on the evening of April 10, 1865, Union soldiers set up printing presses and started producing paroles for the surrendered Confederates. The Federals printed more than 30,000 parole documents here.

Historical significance

The Clover Hill Tavern with its guest house and slave quarters have special meaning in American history as designated by the National Park Service under their criteria by embodying the distinctive characteristics of a type, period, and method of construction in the mid nineteenth century. The buildings and resources constitute a typical farming community of Virginia as well as a government seat (county "court house" seat) of the nineteenth century in the United States. They were all registered and documented in the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.[4]

Physical description

The Clover Hill Tavern is constructed of local brick laid in a Flemish bond. The two-story structure has a full attic. It is thirty-nine feet (12 m) wide by twenty-three feet (7.0 m) deep. The south facade is four-bays with a full-length porch. Brick foundation piers support the porch.[11]

The wood shingle roofs cover both the porch and building. The wood shingle roof on the main building is supported by a corbelled brick cornice. The gable ends have rakes with dentils. The east and west gable ends have external, centered, brick chimneys. The wood paneled doors have fan lights above are found on the south and west sides. There is original stenciling and painting exposed on the plaster in the western room stair enclosure.[5] There is evidence of graining on all the interior trim.[4]

The Clover Hill Tavern structure has four bays on each floor. It has a full length porch on the first floor which is supported on brick foundation piers. The windows are non-operable louvered with two panels. The west side has an entrance with the south side being the main entrance. The rear of the building is identical to the front, except in reverse. The building has a full attic and no cellar. The Clover Hill Tavern was restored in 1954 by the Park.[4]

Guest house and kitchen

The guest house and kitchen associated with the Clover Hill Tavern was originally constructed around 1819.[6] It is a separate independent three-story brick structure that was used as another tavern dining room and overflow guest rooms.[6] The guest house building was reconstructed and renovated in 1954 and rehabilitated in 1997.[12]

The self-standing separate structure is located northwest of the Clover Hill Tavern, which was refurbished in 1953.[12] The first floor was an additional kitchen and the second story was used for additional guest rooms.[9] It is thirty-two feet (9.8 m) wide and eighteen feet (5.5 m) deep.[5] It has a full finish attic, but no cellar.[5]

The south side has four bay windows on the second floor with two board and batten doors at the center flanked sash windows. The first floor has three bay windows with two board and batten doors with one sash window at the west end. There are steps to the second porch at the east end of the first floor. The gable end elevations have centered projecting chimneys with no openings. There are two rooms on each of the first two stories. There is a huge fireplace in the bigger room on the first floor. The fireplace has an original iron crane and no trim nor mantel. The other room on the first floor also has a fireplace. The baseboards in the rooms are almost six inches high and come with a quirk bead. There is only an exterior staircase to the upper stories. A wood shingle gable roof with a box cornice covers the 3-story guest house structure.[12]

Clover Hill Tavern slave quarters

The Clover Hill Tavern slave quarters is a single-story frame cabin with an attic that was originally constructed in 1819. It is fifteen feet (4.6 m) wide by twenty-eight feet (8.5 m) deep. It is four bays with a central fireplace and chimney. The cabin is sheathed in random board and batten. The roof is square-butt wood shingles and finished with plain box cornices and rakeboards.[5]

The slave quarters contributes to the Tavern and the Clover Hill village scene as it was at the time of the surrender of General Lee to General Grant in 1865. The present structure is a reconstruction of the 1819 slave quarters that was rebuilt in 1954.[5]

Footnotes

- Appomattox Court House NHP, 2019 yearly visitation National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- National Register of Historic Places 66000827 National Park Service. Retrieved 2020-05-28.

- Marvel, A place called Appomattox, has an extensive bibliography (pp. 369-383) which lists manuscript collections, private papers and letters that were consulted, as well as, newspapers, government documents, and other published monographs that were used in his research of Appomattox.

- "Clover Hill Tavern". Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2020-06-04. National Park Service

- Jon B. Montgomery; Reed Engle; Clifford Tobias (May 8, 1989). National Register of Historic Places Registration: Appomattox Court House / Appomattox Court House National Historical Park (version from Virginia Department of Historic Resources, including maps) (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (pdf) on January 15, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009. and Accompanying 12 photos, undated (version from Federal website) (32 KB) and one photo, undated, at Virginia DHR Archived 2009-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- Gutek, p. 299

- Marvel, A Place Called Appomattox, p. 1-6

- Brown, p. 121

- "The printing of paroles". Retrieved 2020-06-04.

- "Clover Hill Tavern". Stone Sentinels. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- "Clover Hill Tavern - The printing of Paroles for the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia". Archived from the original on 11 August 2007. Retrieved 2009-01-26.

- "Historic Structures at Appomattox Court House". Retrieved 2020-06-04. National Park Service

Sources

- Brown, Ann Eckert, American Wall Stenciling, 1790–1840, UPNE, 2003, ISBN 1-58465-194-6

- Gutek, Patricia, Plantations and Outdoor Museums in America's Historic South, University of South Carolina Press, 1996, ISBN 1-57003-071-5

- Marvel, William, A Place Called Appomattox, UNC Press, 2000, ISBN 0-8078-2568-9

Further reading

- Davis, Burke, To Appomattox - Nine April Days, 1865, Eastern Acorn Press, 1992, ISBN 0-915992-17-5

- Kaiser, Harvey H., The National Park Architecture Sourcebook, Princeton Architectural Press, 2008, ISBN 1-56898-742-0

- Kennedy, Frances H., The Civil War Battlefield Guide, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1990, ISBN 0-395-52282-X

- National Park Service, Appomattox Court House: Appomattox Court House National Historical Park, Virginia, U.S. Dept. of the Interior, 2002, ISBN 0-912627-70-0

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clover Hill Tavern. |