Coffee production in Ethiopia

Coffee production in Ethiopia is a longstanding tradition which dates back dozens of centuries. Ethiopia is where Coffea arabica, the coffee plant, originates.[1] The plant is now grown in various parts of the world; Ethiopia itself accounts for around 3% of the global coffee market. Coffee is important to the economy of Ethiopia; around 60% of foreign income comes from coffee, with an estimated 15 million of the population relying on some aspect of coffee production for their livelihood.[1] In 2006, coffee exports brought in $350 million,[2] equivalent to 34% of that year's total exports.[3]

History

The coffee plant, Coffea arabica, originates in Ethiopia.[1] According to legend, the 9th-century goatherder Kaldi in the region of keffa discovered the coffee plant after noticing the energizing effect the plant had on his flock, but the story did not appear in writing until 1671.[4]

Production

.jpg.webp)

Ethiopia is the world's seventh largest producer of coffee, and Africa's top producer, with 260,000 metric tonnes in 2006.[5] Half of the coffee is consumed by Ethiopians,[6] and the country leads the continent in domestic consumption.[7] The major markets for Ethiopian coffee are the EU (about half of exports), East Asia (about a quarter) and North America.[8] The total area used for coffee cultivation is estimated to be about 4,000 km2 (1,500 sq mi). The exact size is unknown due to the fragmented nature of the coffee farms.[9] The way of production has not changed much, with nearly all work, cultivating and drying, still done by hand.[6]

The revenues from coffee exports account for 10% of the annual government revenue, because of the large share the industry is given very high priority, but there are conscious efforts by the government to reduce the coffee industry's share of the GDP by increasing the manufacturing sector.[10]

The Tea and Coffee Authority, part of the federal government, handles anything related to coffee and tea,[9] such as fixing the price at which the washing stations buy coffee from the farmers. This is a legacy from a nationalization scheme set in action by the previous regime that turned over all the washing stations to farmers cooperatives.[11] The domestic market is heavily regulated through licenses, with the goal of avoiding market concentration.[11]

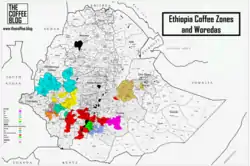

Regional varieties

Ethiopian coffee beans that are grown in either the Harar, Yirgacheffe or Limu regions are kept apart and marketed under their regional name.[7][12] These regional varieties are trademarked names with the rights owned by Ethiopia.[13]

Sidamo[14]

It is very likely that in and around this region is where coffee had its origins. Sidamo coffee is well-balanced with cupping notes exhibiting berries and citrus with complex acidity. The coffee hails from the province of Sidamo in the Ethiopian highlands at elevations from 1,500 up to 2,200 meters above sea level. At these elevations the coffee beans can be qualified as “Strictly High Grown” (SHG). Here the Ethiopian coffees grow more slowly and therefore have more time to absorb nutrients and develop more robust flavors based on the local climate and soil conditions. The most distinctive flavour notes found in all Sidamo coffees are lemon and citrus with bright crisp acidity. Sidamo coffee includes Yirgachefe Coffee and Guji Coffee. Both coffee types are very high quality.

Genika

"Ethiopia Genika" is a type of Arabica coffee of single origin grown exclusively in the Bench Maji Zone of Ethiopia. Like most African coffees, Ethiopia Guraferda features a small and greyish bean, yet is valued for its deep, spice and wine or chocolate-like taste and floral aroma.

Harar

Harar is in the Eastern highlands of Ethiopia. It is one of the oldest coffee beans still produced and is known for its distinctive fruity, wine flavour. The shells of the coffee bean are used in a tea called hasher-qahwa. The bean is medium in size with a greenish-yellowish colour. It has medium acidity and full body and a distinctive mocha flavour. Harar is a dry processed coffee bean with sorting and processing done almost entirely by hand. Though processing is done by hand, the laborers are extremely knowledgeable of how each bean is categorized.

Beans

Ethiopian coffee beans of the species Coffea arabica can be divided into three categories: Longberry, Shortberry, and Mocha. Longberry varieties consist of the largest beans and are often considered of the highest quality in both value and flavour. Shortberry varieties are smaller than the Longberry beans but, are considered a high grade bean in Eastern Ethiopia where it originates. Also the Mocha variety is a highly prized commodity. Mocha Harars are known for their peaberry beans that often have complex chocolate, spice and citrus notes.

Starbucks and Ethiopian coffee

On 26 October 2006, Oxfam accused Starbucks of asking the National Coffee Association (NCA) to block a US trademark application from Ethiopia for three of the country's coffee beans, Sidamo, Harar and Yirgacheffe.[15] They claimed this could result in denying Ethiopian coffee farmers potential annual earnings of up to £47m.

Ethiopia and Oxfam America urged Starbucks to sign a licensing agreement with Ethiopia to help boost prices paid to farmers. At issue was Starbucks' use of Ethiopia's famed coffee brands—Guji, Sidamo, Yirgacheffe and Harar—that generate high margins for Starbucks and cost consumers a premium, yet generated very low prices to Ethiopian farmers.

Robert Nelson, the head of the NCA, added that his organization initiated the opposition for economic reasons, "For the U.S. industry to exist, we must have an economically stable coffee industry in the producing world ... This particular scheme is going to hurt the Ethiopian coffee farmers economically." The NCA claimed the Ethiopian government was being badly advised and this move could price them out of the market.[15]

Facing more than 92,000 letters of concern, Starbucks had placed pamphlets in its stores accusing Oxfam of "misleading behavior" and insisting that its "campaign need[s] to stop". On 7 November, The Economist derided Oxfam's "simplistic" stance and Ethiopia's "economically illiterate" government, arguing that Starbucks' (and Illy's) standards-based approach would ultimately benefit farmers more.[16] In conclusion of this issue, on 20 June 2007, representatives of the Government of Ethiopia and senior leaders from Starbucks Coffee Company announced that they had executed an agreement regarding distribution, marketing and licensing that recognizes the importance and integrity of Ethiopia's specialty coffee designations.[17] Financial terms regarding this agreement were not disclosed.

Starbucks, as part of the deal, also was set to market Ethiopian coffee during two promotional periods in 2008. A Starbucks spokesman said the announcement is "another development" in the relationship with Ethiopia and a way to raise the profile of Ethiopian coffee around the world.

An Oxfam spokesman said the deal sounds like a "useful step" as long as farmers are benefiting, and it's a big step from a year ago when Starbucks "wasn't engaging directly (with) Ethiopians on adding value to their coffee".[17]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coffee in Ethiopia. |

References

- Thomas P. Ofcansky, David H. Shinn (29 Mar 2004). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. p. 92. ISBN 9780810865662.

- "CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- "CIA World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 20 July 2010.

- Weinberg & Bealer 2001, pp. 3–4

- "Food and Agricultural commodities production". Food and Agriculture Organization. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- Cousin, Tracey L (June 1997). "Ethiopia Coffee and Trade". American University. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2010.

- "Major coffee producers". National Geographic Society. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- Keyzer, Merbis & Overbosch 2000, p. 33

- Belda 2006, p. 77

- Belda 2006, p. 79

- Keyzer, Merbis & Overbosch 2000, p. 35

- Daviron, Benoit; Ponte, Stefano (2005). The coffee paradox: global markets ... - Google Books. ISBN 9781842774571. Retrieved 2011-02-07.

- "Starbucks in Ethiopia coffee vow". BBC. June 21, 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-21.

Starbucks has agreed a wide-ranging accord with Ethiopia to support and promote its coffee, ending a long-running dispute over the issue.

- https://aromacoffee.ae/articles-2/ethiopian-sidamo-coffee/

- "Starbucks in Ethiopia coffee row". UK: BBC News. 26 October 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2009.

- "Oxfam versus Starbucks: And this time, Oxfam may be wrong". The Economist. 7 November 2006. Retrieved 2 November 2009. (subscription required)

- Craig Harris (28 November 2007). "Starbucks chairman, Ethiopia talk beans". Seattle PI. Retrieved 20 March 2015.

External links

- Bibliography

- Belda, Pascal (2006), Ethiopia, MTH Multimedia S.L., ISBN 978-84-607-9667-1.

- Keyzer, Michiel; Merbis, Max; Overbosch, Geert (2000), WTO, agriculture, and developing countries: the case of Ethiopia, Food & Agriculture Org., ISBN 978-92-5-104423-0.

- Weinberg, Bennett Alan; Bealer, Bonnie K (2001). The world of caffeine : the science and culture of the world's most popular drug. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-92722-6.