Comanche history

Forming a part of the Eastern Shoshone linguistic group in southeastern Wyoming who moved on to the buffalo Plains around AD 1500 (based on glottochronological estimations), proto-Comanche groups split off and moved south some time before AD 1700.[1] The Shoshone migration to the Great Plains was apparently triggered by the Little Ice Age, which allowed bison herds to grow in population.[1] It remains unclear why the proto-Comanches broke away from the main Plains Shoshones and migrated south. The desire for Spanish horses released by the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 may have inspired the move as much as pressures from other groups drawn to the Plains by the changing environment.[1]

- For a summary of Comanche history see Comanche.

The Comanche's autonym is nʉmʉnʉʉ, meaning "the human beings" or "the people".[2] The earliest known use of the term "Comanche" dates to 1706, when Comanches were reported to be preparing to attack far-outlying Pueblo settlements in southern Colorado.[3] The Spanish adopted the Ute name for the people: kɨmantsi (enemy).[4]

From a population estimated at 20,000 to 40,000 in the 1780s, total Comanche population declined, because of disease and warfare, to about 1,500 in 1875.[5][6] In 1920 the United States Census listed fewer than 1,500. Comanche tribal enrollment in the 21st century numbered 15,191, with approximately 7,763 members residing in the Lawton-Fort Sill and surrounding areas of southwest Oklahoma. Of the three million acres (12,000 km²) promised the Comanche, Kiowa and Kiowa Apache by treaty in 1867, only 235,000 acres (951 km²) have remained in native hands. Of this, 4,400 acres (18 km²) are owned by the tribe itself.

Comanche expansion: 1700-1800

Between 1700 and 1750, the Comanche mostly resided in the central plains of eastern Colorado and western Kansas, between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers. From here they fought not only with the Spanish, Ute and Apache, but with most of the tribes of the central plains. It is believed that contact with Europeans was made when Comanches accompanied the Ute to a trade fair in Taos, around 1700.

Spanish

Spain had relatively neglected Texas during the 17th-century, but this ended when the French began to expand west from Louisiana. A mission-presidio was built at Nagadoches in 1716, followed by other missions and settlements in eastern Texas. These were generally beyond the usual range of Comanches, but not beyond the effects of the Comanche war with the Plains Apache. By 1728, several groups of Plains Apache had retreated into southern Texas and were pressed up against the mid-Rio Grande. They generally annihilated or absorbed the Coahuiltecan, Chisos, Jano, and Manso peoples they found there, and began to raid northern Mexico. These groups of Apache became known as Lipan, and they not only alternately fought and traded with the Tonkawa and Caddo tribes in eastern Texas, but were dangerous to the Spanish. They also continued to fight with Comanches, and this, together with French trade along the Red River, drew Comanches east and south into northern Texas.

Beginning in the 1740s the Comanches began crossing the Arkansas River from their previous range of between the Platte and Arkansas Rivers in eastern Colorado and western Kansas, and established themselves on the edges of the Llano Estacado (Staked Plains) which extended from western Oklahoma across the Texas Panhandle into New Mexico.

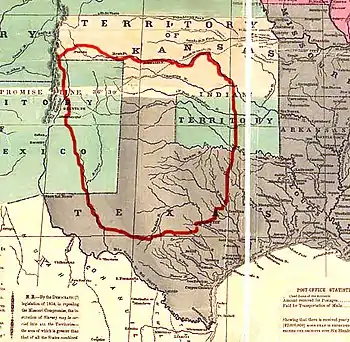

The area they controlled became known as Comancheria, and extended south from the Arkansas River across central Texas to the vicinity of San Antonio (including the entire Edwards Plateau west to the Pecos River), and north following the foothills of the Rocky Mountains to the Arkansas.

The earliest mention of Comanches in Texas was in 1743, when they were attacking the Lipan Apache. Some accounts call them Norteños, a collective term that probably included Wichita and Pawnee. The Spanish solution to Lipan hostility was to convert them to Christianity, but like most Apache, they were not very receptive. However, the Lipan, who had little love for the Spanish, saw an opportunity to lure the Spanish and Comanches into a war. In 1757 they approached the Spanish priests and requested that a mission be built for them. The suggested location was on land the Lipan knew was claimed by Comanches. The Spanish took the bait and built the Mission Santa Cruz de San Sabá and the Presidio San Luis de las Amarillas near present-day Menard, Texas. The Lipan plot worked perfectly. Comanche and Wichita warriors massacred the priests, burned the mission, and attacked the presidio. When the Spanish tried to retaliate, Colonel Diego Parilla's army was defeated by the Wichita and Comanches on the Red River in 1759 in the Battle of the Twin Villages.

In 1761 Comanche raiders struck a second mission for the Lipan on the Nueces River, and the Lipan had the war they wanted. For the next twenty-five years, Comanche raids struck throughout eastern Texas and across the Rio Grande into northern Mexico. The fighting and raiding evolved into three separate wars - Comanches versus Spanish, Comanches versus Lipan, and Lipan versus Spanish.

The French transferred Louisiana to Spain in 1763, but this did not change the trading patterns of the eastern groups of Comanches. Spain continued to administer Texas from Mexico City, while Louisiana was placed under the control of the Viceroy of Havana. Meanwhile, French traders from Louisiana continued to use the Wichita to trade for Comanche horses just as before. By 1770 Spain had gained better control of Louisiana, and for the next three years the Spanish used the French traders to make their first peace overtures to the Wichita and eastern Comanches. There was some success with the Wichita, but Comanche raids into Texas continued until a major smallpox epidemic (1780–81) decimated both the Wichita and Comanches.

By 1778 the Lipan and other Apaches along the Rio Grande had become a major problem for the Spanish, and they began to consider the possibility of an alliance with the Wichita and Comanches against the Apaches. After several small military successes against Comanche raiders, Texas Governor Domingo Cabello y Robles sent Pedro Vial as an emissary to the Wichita villages in 1785 to discuss a peace agreement with the eastern bands of Comanche. By September they had agreed to a peace treaty which was signed in October at Bexar. In exchange for gifts and a promise of regular trade with Texas, the eastern Comanches agreed to help the Spanish fight the Lipan and to urge the western Comanches to make peace with New Mexico. As a result, New Mexico's war with the Comanches ended the following year.

New Mexico's peace endured because of Comanchero trade and lavish gifts, but for Texas and northern Mexico, the peace achieved was only relative. During 1786, many of the Comanche treaty chiefs in Texas either died or were killed. As a consequence, groups of Texas Comanches resumed raiding, but the number of raids never returned to previous levels.

Apache

By 1716, attacks by mounted Comanches had driven the Jicarilla Apache into the mountains of northern New Mexico, while other Plain Apaches had abandoned many of their settlements north of the Arkansas River, and were rapidly giving way across northeastern New Mexico, the Texas Panhandle, and western Oklahoma. Only a few Apache settlements still remained above the Arkansas River. During the summer of 1716, Comanches and Ute visited several settlements in New Mexico to trade. Believing that the true purpose of these visits was to spy for defensive weaknesses, the Spanish attacked a Comanche-Ute village northwest of Santa Fe. Prisoners were later sold as slaves.

In 1719 the first recorded Comanche raids for horses in New Mexico occurred. A Spanish military expedition was sent to retaliate, and travelled as far north as the Arkansas River (Pueblo, Colorado), but found only abandoned campsites. Meanwhile, the advance of the Comanches had destabilized the entire region, and the Apache retreat southward had become a major problem for the Spanish. Groups of refugee Plains Apache (Lipan and Mescalero) concentrated in southern Texas and New Mexico and began to attack the nearby Spanish settlements.

Other Apache bands continued west across southern New Mexico into Arizona, threatening to isolate Santa Fe from El Paso and northern Mexico. To make matters worse for the Spanish, persistent rumors of French traders on the plains were reaching Santa Fe. A military expedition sent to investigate in 1720 was annihilated (probably by Pawnee). Sometime during 1723 the war between the Comanches, Utes, and Plains Apache reached its climax. Two Spanish military expeditions sent to help the Apache failed to locate either Comanches or Ute.

In 1724 a critical nine-day battle was fought at El Gran Cerro del Fierro (Great Mountain of Iron), resulting in a major defeat for the Apache. Within a few years, the last Apache settlements along the upper Arkansas River had disappeared.

New Mexico historian Sherry Robinson doubts that the nine-day battle actually occurred. "The hatred was real but probably not the battle. The teller of this tale, decades after it allegedly occurred, was the Apache-hating Texas Governor Domingo Cabello y Robles. Lipan anthropologist Enrique Maestas dismisses the story as folklore or one of many battles between Apaches and Comanches. Anthropologist Morris Opler wrote that 'authenticated nine-day battles between tribes are not too common in American Indian annals. Yet this bit of recorded hearsay — far removed in time and space from the putative event— has been cited with all earnestness again and again.'" [7]

Ute

By 1730, the Comanches, still living north of the Arkansas, controlled the Texas Panhandle, central Texas and northeastern New Mexico. At about this time, the alliance between the Comanches and the Ute collapsed, marking the beginning of a fifty-year war. Their warfare was sporadic, and never reached the intensity of the struggle with the Apache. At first the Ute held their own, but as the full weight of the Comanche came to bear, they were forced to retreat from the plains into their mountain strongholds.

By 1749, the Ute were asking the Spanish for protection against Comanches, and in 1750, they entered into an alliance with the Jicarilla against their common enemy. Although the warfare between the Ute and Comanche continued until 1786, groups of the Kotsoteka felt confident enough during the 1740s to cross the Arkansas River and move into northeast New Mexico. Other Comanche groups followed after 1750 and settled on the perimeter of the Staked Plains of the Texas Panhandle. However, large numbers of Yamparika and Jupe remained north of the Arkansas until the early 19th century. As the Ute gave ground, the Comanche became dominant, and constituted a serious problem for New Mexico. During the late 1720s, groups of Plains Apache (friendly with the Spanish) had chosen to settle near the Rio Grande pueblos rather than retreat farther south.

New Mexico

In 1725 the Spanish had noted that the Comanches were still using dogs for transport. By 1735 this was no longer the case, and the Comanches had more than enough horses for their own needs. However, they were now supplying them to other plains tribes through trade. The level of horse thefts by Comanches bothered the Spanish, but was bearable, and the trade with Comanches for buffalo robes and slaves was important for the New Mexican economy, so the Spanish continued to trade, but a military expedition was dispatched in 1742 which unsuccessfully tried to stop the raids.

In the early 1720s the Comanche began trading with the French. After the French arranged a peace between the Comanches and Wichita in 1747 (reconfirmed in 1750), the exchange of French trade goods for Comanche horses expanded rapidly. In Texas the Comanche and Wichita defeated a Spanish expedition in 1759 in the Battle of the Two Villages. The Spanish in New Mexico also became alarmed, as the Comanches were now armed with French firearms, which they paid for with horses and mules stolen in New Mexico. Beginning with the Comanche raid on Pecos in 1746, New Mexico was under siege. For the next forty years Comanche raids struck virtually every place in Spanish New Mexico. Both Taos (1760) and Pecos (1746, 1750, 1773, and 1775) were attacked by the Comanche. Some of the Comanche continued to trade peacefully, as the Comanche were not a unified tribe, but several independent divisions, each with the power to make war or peace.

Another Spanish military campaign against the Comanche in 1768 ended in frustration. The Comanche had blocked Spanish expansion to the east from New Mexico and prevented direct communication with the new Spanish settlements in Texas. The Spanish enjoyed their first military success against the Comanche in 1774 when a combined force of 600 soldiers, militia, and Pueblo Indians under Carlos Fernandez attacked a Comanche village near Spanish Peaks (Raton, New Mexico) capturing over one hundred prisoners.

In 1779 the new governor of New Mexico, Juan Bautista de Anza, organized a 500-man army with 200 Ute and Apache auxiliaries. His campaign captured a large Comanche village, and, in a later battle, killed Green Horn (Cuerno Verde), an important leader of the Comanche raiders. Raids dropped off noticeably but did not halt entirely. In the summer of 1785, De Anza let it be known that he was interested in making peace with the Comanches if they could agree on a single leader to represent them. The idea took root and received a major push when the Texas Comanche signed a peace treaty that autumn with Texas Governor Domingo Cabello.

Among the New Mexico Comanche, the main opposition to peace was a parabio named White Bull (Toro Blanco). The Kotsoteka assassinated him and scattered his followers. A meeting of the Kotsoteka, Jupe, and Yamparika gave the power to make peace to Ecueracapa. After two meetings at Pecos and another in a Comanche camp early in 1786, De Anza sent a signed treaty to Mexico City in July (ratified in October). De Anza also arranged a truce between the Ute and Comanche, while gaining a Comanche alliance with the Spanish against the Apache.

For many years, the Comanches remained at peace with New Mexico. Regular trade continued, and the New Mexicans who traded with Comanches became known as Comancheros. This trade relationship lasted well into the 1870s, and persisted even when Comanches used weapons and steel provided by Comancheros to fight enemies living in Texas and northern Mexico.

Lakota, Cheyenne, Arikara, Pawnee, Kansa, and Osage

Although many Comanches had moved south of the Arkansas after 1750, the Yamparika and Jupe bands remained to the north of the Arkansas. As late as 1805, the North Platte was still known as the Padouca Fork, and by this time, Padouca meant Comanche. As late as 1775, the Yamparika were still fighting the Lakota and Cheyenne near the Black Hills and raiding the Arikara villages along the Missouri River. Frequent wars also occurred with the Pawnee, Kansa, and Osage, usually over horses. Comanches usually had more horses than they needed; Pawnee, Kansa, and Osage did not, and dealing with a Comanche horse trader could be frustrating. Often, the solution was to shoot the Comanche (having recently acquired guns from French traders on the Missouri River) and take the horse, and this meant war.

Comanches eventually learned how to minimize the advantage of single-shot firearms. Meanwhile, the Pawnee and Osage had their own horses, many of them stolen from Comanches. A major war erupted in 1746 between Comanches and the Osage and Pawnee. In 1750 the Wichita arranged a truce between the Comanches and Pawnee. The immediate effect was to allow the Pawnee and Comanches to ally and defeat the Osage in 1751. Afterwards, the Pawnee left Kansas and moved north to the Platte Valley in Nebraska. At about the same time the Comanches were moving south to the Staked Plains or concentrating closer to the Arkansas River. Despite the physical separation, Pawnees still traveled great distances to steal Comanche horses in Texas and New Mexico. They usually went out on foot and rode back, if successful. The result was more fighting between Comanches and Pawnee (1790–1793 and 1803).

In 1832 the Comanches caught some Pawnee raiders still on foot near the Arkansas River, and killed every one of them. Although defeated by the Pawnee/Comanche alliance in 1751, the Osage continued to expand west during the last half of the 18th century. In the process, there were several wars and regular skirmishes with Comanches. The tall Osage usually got the worst of it when they fought Comanches, and lost another war in 1791. In 1797 Comanches destroyed an entire Osage village near the Kansas-Missouri border.

Kiowa

From the times when they had lived along the upper Platte in Wyoming, Comanches had known and occasionally fought with the Kiowa. Before 1765, the Kiowa had lived in or near the Black Hills of South Dakota, but soon after this they were displaced by Lakota migrating from east of the Missouri River. The Kiowa were forced to move south, first to the upper Platte, then across it into Kansas, and finally the southern plains near the Arkansas River. The move put them in competition for territory with Comanches.

By 1780, their fighting with the Yamparika and Jupe had become serious, although each respected the other's bravery and fighting abilities. Peace between the Kiowa and Yamparika sprang from a chance meeting (and near battle) at a Spanish trading post, probably around 1805. While the Spanish trader nervously tried to keep them separated, a Kiowa warrior volunteered to go with the Comanches and spend the summer. When he returned unharmed in the autumn, the Kiowa and Yamparika met and made peace. The peace process with other Comanche divisions probably took several more years, but in the end, a lasting alliance was made and never broken. This also extended to the Kiowa's unusual friends, the Kiowa-Apache, who must have sounded a lot like Plains Apache to Comanches when they spoke.

Cheyenne and Arapaho

The other major alliance for the Comanches was with the southern branches of the Cheyenne and Arapaho. The area of the central plains vacated by the departure of the Pawnee and Comanches was soon occupied by groups of Cheyenne and Arapaho. At first these newcomers were harassed by just about everyone: Comanches, Kiowa, Pawnee, and Ute, all of whom still claimed the area as hunting territory. With so many enemies, the Cheyenne and Arapaho first formed their own alliance and fought all comers. One of the things that had attracted them south was trade: first with the Spanish in New Mexico, and then with the Americans.

Raiding Mexico: 1779-1870

See: Comanche-Mexico Wars

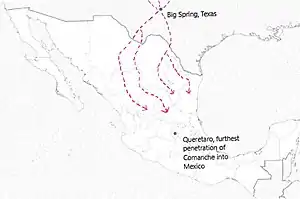

The Comanche raided south of the Rio Grande as early as 1779, their target being the Lipan Apache. In the 1820s the long-term peace the Comanche had forged with Spanish colonies in New Mexico and Texas began to come apart. The newly independent Mexican state could not defend its northern outposts, nor provide the Comanche the yearly tribute to which they were accustomed. Beginning in 1826, responding to the increased threat, the government of Nuevo Leon forbade its citizens in the northern portions of the state to travel in the countryside except in groups of at least 30 armed and mounted men.[8] Large scale raids began in 1840 and continued until 1870. The Comanche and their allies, the Kiowa, raided hundreds of miles south of the border, killing thousands of people and stealing hundreds of thousands of head of livestock. In 1848, traveler Josiah Gregg said that "the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities."[9]

The northern states of Mexico and the soldiers and militia they could muster were left on their own to deal with the Comanche raids. The national government of Mexico was "too incapacitated by fiscal insolvency, civil war, and, ultimately, foreign intervention"[10] to assist the north.

Texas and the United States: 1800-1850

With the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Americans acquired territory that included a portion of Comancheria, but during the next twenty years, American penetration of the Great Plains focused on the fur trade of the Missouri River. On the southern Plains, French traders, now American citizens, continued their contacts with Wichita and Comanches. They were soon joined by an increasing number of Americans. Since much of the trade was conducted through the Wichita, Comanches remained distant and mysterious. American Indian agents in Louisiana were urged to make contacts with the "Hietans."

Several incidents in Texas, including the killing of the son of a Yamparika chief in 1803, almost led to war, but the intervention of the western Comanches maintained peace. In both Texas and New Mexico, Comanches joined with the Spanish army to fight Apaches. The most noteworthy success was when they helped General Ugaldi crush the Lipan in southern Texas (1789–90). The Lipan were badly mauled, and retreated across the Rio Grande into northern Mexico, but this was not beyond the reach of Comanches who continued to attack them for many years.

During the last years of Spanish rule, Texas was in chaos. The Hidalgo Revolt (1810) was followed by an attempt by American and Mexican adventurers to seize Texas (1812–13). American traders along the Red and Arkansas Rivers were trading guns to Comanches for horses, and this new market increased the tempo of Comanche raids in Texas. A Comanche chief, El Sordo, split from his own people in 1810 and gathered a combination of Comanches and Wichita to raid Texas and Mexico for horses. He was arrested during a visit to Béxar in 1811 and imprisoned in Coahuila. A large Comanche war party went to Béxar to demand an explanation, only to be confronted by 600 Spanish soldiers. There was no battle, but relations between Texas and the Comanches were never the same.

Spanish rule was replaced by that of the Mexican Republic in 1821. The following year Francisco Ruiz arranged a truce with the Texas Comanche followed by a treaty of friendship signed in Mexico City in December. However, Mexico did not have the means to provide the gifts it had promised, and raiding resumed within two years. The Comanche peace with New Mexico disintegrated, and by 1825 there was war along the entire length of the Rio Grande. Chihuahua was hit particularly hard. Treaties signed at Chihuahua and El Paso (1826 and 1834) with the Comanches did not halt the raids. In 1831, New Mexico temporarily suspended Comanchero trading and stopped the cibolero (New Mexico buffalo hunters), but this also had little effect.

After the end of Spanish rule of Mexico in 1821, Anglo-Americans began to settle in Texas, increasing contact with the Comanches and other tribes. The Santa Fe Trail opened that year, between Missouri and Santa Fe. Contact between the anglos and Comanches was almost always friendly. There were exceptions, and as the most powerful tribe in the area, the Comanche were sometimes blamed for the actions of other tribes, such as the Wichitas, Pawnee and Osage.

During the 1830s, the major trading center on the southern Plains was Bent's Fort, an American trading post on the Arkansas River in southeast Colorado. Although married to a Cheyenne woman, William Bent also traded with Kiowa and Yamparika, and became tired of the aggravation of keeping them apart when they came to trade. At his suggestion, the Cheyenne and Arapaho decided to meet with their adversaries, and a lasting peace was arranged between them. The "Great Peace of 1840", a landmark of southern Plains diplomacy, was cemented by the gift of large numbers of Yamparika and Kiowa horses to the Cheyenne and Arapaho.

In 1835 Sonora re-established its bounties for scalps. Chihuahua and Durango followed, but by the 1840s, Comanche war parties were ranging all over northern Mexico, some staying for as long as three months. Comanche war parties usually found easy victims in Texas, and when Americans began to settle there after 1821, Comanches did not distinguish between Anglo and Hispanic settlers. In 1833, Sam Houston arrived in Texas as a United States representative to arrange a treaty with the Texas Comanches. There were some meetings, but Mexican officials began to wonder what he was doing in their country arranging a treaty with their Comanches, and he was asked to leave. Soon after Texas won its independence from Mexico in 1836, Houston became president of the new republic.

In May 1836 (less than three months after the Battle of the Alamo), over 500 Comanche and Kiowa warriors approached Fort Parker located 100 miles south of Dallas. Feigning a desire for peaceful trade, the Comanche initiated hostilities and killed five men and captured two women and three children in what became known as the Fort Parker massacre. A 9-year-old girl, Cynthia Ann Parker, was captured and spent most of the rest of her life with the Comanche, marrying a Chief, Peta Nocona, and giving birth to a son, Quanah Parker, who would become the last Chief of the Comanches. The remainder of the Fort Parker residents made a long trek to Fort Houston, ninety miles to the south.

In May 1838, Texas signed a treaty of peace and friendship with the Comanches, but the treat did not address the Comanches' main concern, a line between Comancheria and the white settlements. In the absence of an agreement on this, the whites steadily encroached, and the Comanches continued to raid. Houston wanted to set a line but was replaced in December by Mirabeau B. Lamar, a man determined to deal with problems with Indians by war.

In March 1840, a meeting between Texan officials and Comanche chiefs was held in San Antonio, under a flag of truce, to negotiate the release of thirteen known kidnap victims, mainly women and children, taken by Comanches during the previous ten years of Mexican rule. The chiefs met with the commissioners in the council house, while the accompanying Comanches waited under guard in the Court House yard. The Comanches brought a single captive to the meeting, claiming that the others had been sold on to other tribes. This was disputed by the captive, Matilda Lockhart, who said that other prisoners were being held for later ransoms. The commissioners were outraged, and the negotiations collapsed. Soldiers surrounded the council house to take the Comanche leaders hostage for exchange with the white captives still held. The Comanche chiefs tried to escape, and the Texans killed them. Fierce fighting between the Texans and the Comanches outside soon spread, leading to the deaths of thirty-three Comanches and six Texans.

The Comanches were outraged by the killing of their chiefs under a flag of truce. Hundreds of warriors approached San Antonio screaming their rage, but remained just beyond rifle-range. Then, suddenly, they were gone, and the Texans thought the crisis had passed. The Comanches had left to plan retaliation. When they got back to their camps, they killed many of the white prisoners they were planning to exchange.

Thirty-two Comanches, mostly women, had been taken prisoner. Negotiations led to the release of five white children in exchange for five Comanches. The remaining prisoners were strictly guarded for a time, but the guard was later relaxed, and all eventually escaped.

In August, several hundred Comanche warriors raided the heart of eastern Texas. Homes were burned, hundreds were killed, and before they stopped, the Comanches had reached the Gulf of Mexico near Victoria. Then, loaded with loot, the war party began an atypical slow retreat to the north. Perhaps because of their numbers, the Comanches were overconfident, but this gave the Texans time to organize. With the help of Tonkawa scouts, Texas militia ambushed the main body in the Battle of Plum Creek at Lockhart, Texas. Abandoning most of their spoils, the surviving Comanches escaped north. Afterwards, they would never again give the Texans such an easy target.

The Anglos in Texas were Americans, and the only reasons they had not been annexed by the United States in 1836 were northern Congressional resistance to another slave state and a dispute with Mexico over the southern boundary of Texas. While waiting for admission, the Texans in 1839 expelled the Cherokee, Shawnee, and most of the Delaware that the Mexican government had encouraged to settle in eastern Texas to keep Americans out in the first place. Houston was re-elected president and set about repairing the damage done by Lamar's administration. He not only had to deal with Comanches, but a second war with Mexico (1841–42).

Without resources for a standing army, Texas created small ranger companies mounted on fast horses to pursue and fight Comanches on their own terms. Eventually armed with the first Colt revolvers, the Texas Rangers enjoyed considerable success against Comanches during the 1840s. However, Houston wanted peace, not war, and he was trusted by Comanches.

A treaty between the Republic of Texas and Texas Comanches was signed October, 1845 and ratified in December. It established a line of trading houses which would later function as the line between Texas and Comancheria, but this deliberately vague definition would be the source of future troubles. Spain had been an ally of the Americans for much of the Revolutionary War, but after the rebel triumph in 1783, had become concerned about the territorial ambitions of the new United States. Its fears proved justified as American settlement swept across the Appalachians into the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys. To supply horses and mules for these immigrants, American traders were soon looking to the southern plains and were dealing with Comanches and Wichita.

Dr. John Sibley had the first official meeting with a Comanche "principal chief" in 1807 at Natchitoches. He gave presents, and later licensed an American trader for them. Other licenses followed. One of his successors, John Jamison, had other visits from Comanche chiefs in 1816 and 1817. These contacts and trading licenses were viewed with alarm in Spanish Texas. The traders not only sold firearms to Comanches and Wichitas, but provided a ready market for stolen horses and mules.

American problems with Comanches began during the 1820s with the relocation of tribes from east of the Mississippi River to Kansas and Oklahoma. The problem at first was not much with Comanches, but with the Osage, whose territory was directly affected. To defend themselves against the Osage, the Delaware, Fox, Sauk, Cherokee and others began to consider alliances with Comanches and other Plains tribes. However, when the newcomers began hunting west of their new homes, they came into conflict with Comanches. To preclude the possibility widespread warfare, Colonel Henry Dodge led a large force of dragoons from Fort Gibson to western Oklahoma during the summer of 1835 as a show of force and to meet the Comanches. In August, the Hois (with the Wichita) signed the Camp Holmes Treaty with American representatives, pledging peace and friendship with the Osage, Quapaw, Seneca, Cherokee, Choctaw, and Creek. The treaty also reflected another American concern and guaranteed safe passage on the Santa Fé trail.

Within a year the Comanches regretted this agreement, and had destroyed their copy. When the United States annexed Texas in 1846, it inherited its problem with Comanche raiding and a boundary line between the settlements and Comancheria. An immediate step by the United States was to announce its authority and sign a treaty with the Comanches and other Texas tribes to replace the Texas treaty of the previous year. This was done in May 1846 on the upper Brazos River (Butler-Lewis Treaty). Signed by the Penateka/Hois Comanches (also Ioni, Anadarko, Caddo, Lipan Apache, Wichita, and Waco), the treaty promised, besides peace and friendship, trading posts, a visit by a Comanche delegation to Washington, D.C., and a one-time payment of $18,000 in goods. A boundary line was alluded to, but not defined.

The Comanche delegation went east shortly afterwards and met President James K. Polk, but with the Mexican War just beginning, Congress had more important concerns, and the Senate adjourned without ratifying the treaty. By the time the treaty was amended and ratified in March 1847, the Comanches were certain they had been betrayed. War was averted only when traders and Indian agents advanced credit to send part of the promised gifts. When the amendments were read to the Comanches, the meeting almost ended, but eventually they agreed to the changes. Additional money was appropriated for more gifts, but once again, a boundary line was never established.

Meanwhile, there was a serious question over whose responsibility it was to deal with the Texas tribes, the federal or the state government. The problem was not settled until after the Civil War. In the interim, policy was set by both, and this was confusing, so the 1846 peace treaty brought very little peace to Texas.

In May 1847, Texas allowed the German settlers near Fredericksburg and New Braunfels to make their own treaty with the Texas Comanches. In exchange for land, the Germans promised a trading post and gifts. Unfortunately, the Germans not only encroached beyond the agreed boundary, but were slow to pay, and in response the Comanches made raids. A boundary line was eventually set by the Texas governor but was to be enforced by the American army which had taken over the line of Texas forts on the frontier. Army commanders felt they had no authority to enforce state laws, and meanwhile, Texas continued to operate its ranger companies, which were not under federal control, as military units. The Rangers did nothing to prevent encroachment on Comanche lands but would retaliate if the new settlements beyond the line were attacked. To make matters worse, only the Penateka had signed the 1846 treaty. The Nokoni, Tenawa, and other Comanches did not consider themselves bound by the agreement and continued to raid in Texas.

On the other side of Comancheria, many things had changed with the beginning of the Mexican War in 1846. An American army under General Stephen W. Kearny seized Santa Fé and moved on to California. The Santa Fé Trail became a heavily-travelled military supply route, and forts were built to protect it. Five companies of Missouri volunteers were sent to garrison these posts during the summer of 1847 and quickly became engaged in fights with Plains Indians. At least one of these at Fort Mann involved the Pawnee. In the other cases, the fights were probably with Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho, and the amount of Comanche involvement is uncertain.

The first part of 1848 was relatively calm, and during that year, Texas Comanches even provided guides for the survey of the route of the new Butterfield (California) trail across southern Texas to El Paso and California. The calm changed suddenly with the California Gold Rush. As thousands of gold-seekers raced west, they needed horses, and the Comanches moved to meet this new demand. Horse raids increased in Texas, but the major target was northern Mexico. Comanche raids struck deep into Coahuila, Chihuahua, Sonora, and Durango, reaching their peak during 1852 when they struck Tepic in Jalisco, 700 miles (1,100 km) south of the border at El Paso. To protect the immigrant routes across the plains, the United States called the "Peace on the Plains" conference at Fort Laramie (Wyoming) in 1851. This was an attempt to end, or at least limit, intertribal warfare by defining boundaries between tribal territories.

Almost every plains tribe attended and signed the 1851 Fort Laramie Treaty, and received gifts. The Comanches and Kiowa did not attend. A smallpox epidemic had broken out in their villages, and there was a deep distrust of the northern tribes. Since the Santa Fé Trail was a vital route, it was essential to reach an agreement with them. As the southern Plains tribes gathered around Fort Atkinson for the distribution of the annuities from the Fort Laramie treaty, large groups of Kiowa and Comanches also came, and they were not in a good mood.

Eventually, 6,000 to 9,000 Indians were gathered in the vicinity, and the situation was becoming dangerous. The American agent took it upon himself to distribute $9,000 in gifts to the Comanches and Kiowa, and in 1853 the Kiowa and Yamparika signed their own treaty at Fort Atkinson. In return for safe passage and a promise to stop raiding in Mexico, the United States agreed to pay those tribes $18,000 per year for ten years.

United States: 1850-1900

There were several reasons the Comanches and Kiowas had been angry in 1852. The first was they had recently been devastated by epidemics of smallpox and cholera. Their first experience with smallpox had been an epidemic (1780–81) so severe that it caused the disappearance of some Comanche divisions. The Comanche were hit again by smallpox during the winter of 1816–17. The wave of immigration from the California Gold Rush first brought smallpox (1848) and then cholera (1849) to the Great Plains. These were devastating to every plains tribe, but especially to the Comanches and Kiowa. The government census estimated a drop in the Comanches' 1849 population of 20,000 to 12,000 by 1851, and the Comanches never recovered from this loss. Smallpox struck again from New Mexico during 1862 and is believed to have been equally devastating. Cholera returned in 1867. By 1870, the Comanches numbered less than 8,000, and their numbers were still dropping rapidly.

The Comanches kept their promise for safe passage on the Santa Fe Trail, but remained angry about events in Texas. White settlement was steadily taking more and more of Comancheria, and the Texas Rangers were still attacking them. As the frontier advanced, the American army had built a new line of forts, followed by a third line. At first these had been manned by infantry, and the Comanche simply by-passed them. Within a few years, the infantry was replaced by new light-cavalry regiments. In all, it took three lines of forts and most of the army's pre-Civil War strength to keep the Comanches out of Texas.

Even more aggravating from the Comanches' point of view were posts like Fort Stockton at Comanche Springs, which were intended to block the "Great Comanche War Trail" leading to northern Mexico. The Americans were required by the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to prevent raids into Mexico. Between 1848 and 1853, Mexico filed 366 separate claims for Comanche and Apache raids originating from north of the border.

Not all efforts to deal with the Texas Comanches were limited to military force. In 1854 the Texas legislature provided 23,000 acres (93 km²) for the United States to established three reservations on the upper Brazos River for the Texas tribes. Besides Caddo, Delaware, Wichita, and Tonkawa, the United States Indian agent, Robert Neighbors, convinced some Penateka Comanche to move to these locations. Camp Cooper (commanded in 1856 by LTC Robert E. Lee) was built nearby. Almost immediately, local settlers began to accuse the reservation tribes of stealing horses and other depredations. Many of these accusations were either exaggerations, lies, or referred to raids by Comanches from the Staked Plains. The situation became dangerous in 1858 after the army abandoned Camp Cooper.

During the spring of 1859, a mob of 250 settlers attacked the reservation, but were repulsed. As the United States Indian Agent, Robert Neighbors was hated by local Texans. Rather than fight them, he arranged to close the reservations and move the residents to Indian Territory. The peaceful Penateka were forced to leave Texas, along with tribes that had never fought Texans, including the Tonkawa, Caddo, and Delaware, who had served loyally as scouts for the Texas Rangers.

After leaving his charges at the new Wichita agency at Anadarko, Neighbors started back to his home in Texas. He never made it. Near Belknap, Texas he was ambushed and shot in the back.

After its victory against the Brazos reservation, Texas urged the army to make greater efforts against Comanches beyond its borders. Texas Rangers had discovered that Kiowa and Comanches were using the Indian Territory as a sanctuary from which to raid in Texas and then elude pursuit.

Between 1858 and 1860, the army's new light-cavalry regiments were used for an offensive against Comanches in Oklahoma. In May, 1858 Colonel John Ford's Texas Rangers, ignoring the state-line, attacked a Comanche village on Little Robe Creek. Three months later his Caddo, Delaware, and Tonkawa scouts were expelled from Texas as undesirables. In October, 1858 Captain Earl Van Dorn attacked a Comanche village at Rush Springs killing 83. The following May, Van Dorn struck the Comanches at Crooked Creek in Kansas.

The result of this offensive by the army and Rangers was to cause trouble elsewhere. Attacked from Texas, Comanches and Kiowa separated into small bands and moved north near the Santa Fe Trail. In response to increased Indian attacks on the trail during the summer of 1860, three columns of cavalry were sent into the area on a punitive expedition. In July, the command of Captain Samuel D. Sturgis made a major contact. After an eight-day chase, he fought a battle with Kiowa, Cheyenne, Arapaho, and, presumably, some Comanches.

When federal soldiers withdrew east at the beginning of the Civil War, Confederates replaced them. Albert Pike, the Confederate Indian agent, signed two treaties with Comanches in August, 1861; one with the Penateka, and a second with the Nokoni, Yamparika, Tenawa, and Kotsoteka. Besides the usual promises of peace and friendship, the Comanches were promised a large amount of goods and services. Because the Confederacy needed every cent it had to fight the war, the Comanches never received what was promised.

When Texas sent its men east to fight for the Confederacy, most of the old federal army posts were abandoned. With the frontier defenseless and the Confederate treaty promises unfulfilled, Comanches began raids intended to drive settlement back. The Texas frontier retreated over 100 miles (160 km) during the Civil War, and northern Mexico was hit by a new wave of Comanche raids.

The war also provided the Comanches with an opportunity to seek revenge against the Tonkawa. and not just for their service as scouts with the Texas Rangers; the Texas Comanches had a special hatred for the Tonkawa ever since they had killed and eaten the brother of one of their chiefs. The Comanches were not a gentle people, but they found cannibalism repulsive.

After Texas Indian agents had taken over administration of the Wichita Agency in Oklahoma, Comanches participated in an attack on the agency (October, 1862) by pro-Union Delaware and Shawnee from Kansas. When it was over, 300 Tonkawa had been massacred. The survivors crossed the Red River and settled near Fort Griffin. In the years following, they would exact their revenge by serving as army scouts against the Comanches.

After 1861 Comanches, Kiowa, Cheyenne and Arapaho almost succeeded in closing the Santa Fé Trail. When federal officials at Fort Wise learned the Comanches had signed treaties with the Confederacy, they were certain that they had become hostile. While the rest of the nation was bleeding itself to death on eastern battlefields, the ranks of the Union army on the frontier were filled with men who were unemployed, did not wish to fight in the war, and hated Indians. By the fall of 1863, the performance of these "soldiers" had provoked a general alliance between the Lakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, Comanches, and Kiowa-Apache.

In the autumn of 1864, Colonel Kit Carson was sent at the head of a column from Fort Bascom, New Mexico into the Staked Plains to chastise the Comanches and Kiowa. His Jicarilla and Ute scouts located their camps on November 24. Carson had found more Comanches and Kiowa than he could chastise, and the First Battle of Adobe Walls came very close to being "Carson's Last Stand." Only the skillful use of artillery kept the Yamparika and Kiowa from massing and overrunning his position. Afterwards, Carson returned to New Mexico and left the chastising of Comanches to others.

In the final days of the Civil War, the Confederacy made a final attempt to exploit the hostility of the plains tribes that had been provoked by the federal volunteers. In May, 1865 a council was held on the Washita River in western Oklahoma. It was well attended by the Comanches and other tribes, but Robert E. Lee had surrendered in Virginia two-weeks previously, and the Confederacy was finished.

That summer, while the Union celebrated its victory, the plains were in turmoil. The Santa Fé and Overland trails were closed, and virtually every plains tribe was at war with the United States. As federal troops began to re-occupy their posts in Texas, the Great Plains and Indian Territory, government commissioners met with the plains tribes in October on the Little Arkansas River near Wichita to arrange a peace. The Little Arkansas Treaty gave the Comanches and Kiowa western Oklahoma, the entire Texas Panhandle, and promised annuities of $15 per person for forty years.

Of the Comanche divisions, only the Yamparika, Nokoni, Penateka, and Tenewa had taken part in the agreement; the Kwahada and Kotsoteka had not. The Kiowa-Apache did not sign the Comanche-Kiowa version but asked to be included under the Cheyenne-Arapaho treaty. This served as an indication of how unstable the situation was. When the annuities arrived, there was widespread disappointment. The Comanches had expected guns, ammunition, and quality goods; what they got were rotten civil war rations and cheap blankets that fell apart in the rain. The peace was soon violated by both sides, and war resumed for another two years. It was a bitter struggle, and General William Sherman finally ordered the army not to pay ransom for white captives held by Indians to avoid giving them incentive for further kidnappings.

While the army was making its own plans to deal with the hostiles by force, the federal government decided to make one final effort to resolve the conflict through treaty. The result was a milestone peace conference held at Medicine Lodge Creek in southern Kansas (October, 1867). In exchange for a wagon train of gifts brought by the commissioners and the payment of annual annuities, the Comanches and Kiowa signed the Medicine Lodge Treaty exchanging Comancheria for a 3 million acre (12,000 km²) reservation in southwestern Oklahoma. The arrangement did not work as intended. Because of an outbreak of cholera in their camps, the Kwahada neither attended the conference nor signed the treaty. Afterwards, they did not consider themselves bound by the Medicine Lodge Treaty, and chose to stay on the Staked Plains.

Most of the other Comanches moved to the vicinity of Fort Cobb and remained on the reservation for the winter, but since the treaty was not yet ratified, there was no money to pay for rations. After a hungry winter, most of the Comanches and Kiowa left Fort Cobb, and returned to the plains during the summer of 1868. Once again raids were made into Texas and Kansas, and the new reservation was used as a sanctuary to prevent pursuit by the army. Even Fort Dodge was attacked, and its horses stolen. The frustrated Indian agent at Fort Cobb resigned and went east, leaving the mess in the hands of his assistant.

The treaty was ratified in July, and funds were made available, but the responsibility for the administration of annuities was placed with the army. After all tribes were ordered to report to Fort Cobb or be considered hostile, General Philip Sheridan set plans in motion for the winter campaign of 1868–69 against the hostiles in western Oklahoma and the Staked Plains. LTC George Custer and the 7th Cavalry attacked a southern Cheyenne village on the Washita River in November, and Major Andrew Evans struck a Comanche village at Soldiers Spring on Christmas Day. Afterwards, most of the Comanches and other tribes still on the plains returned to the agencies.

In March, 1869 the Comanche-Kiowa agency was relocated to Fort Sill and the Cheyenne-Arapaho agency to Darlington. Only the Kwahada were still on the Staked Plains. The Kiowa and other Comanches were on the reservation, but by the fall of 1869 small war parties were occasionally leaving to raid in Texas. During one of these raids near Jacksboro (May, 1871), the Kiowa almost killed William Sherman, commanding general of the American army. "Great Warrior" Sherman was conducting an inspection tour of western posts, when a Kiowa war party noticed his lone ambulance and small escort. They chose instead to attack a nearby supply train. When Sherman learned of his narrow escape, he was furious and proceeded directly to Fort Sill. When he discovered the Kiowa chiefs were openly bragging about the latest raid, he ordered their arrest and sent them to Texas for trial. After a Texas court sentenced them to life imprisonment, the Comanches and Kiowa launched a series of retaliatory raids that killed more than 20 Texans in 1872. At the same time, Texas civilians stole 1,900 horses from the tribes at Fort Sill.

Meanwhile, the army in Texas was trying to deal with the raids from the reservation and massive thefts of Texas cattle by the Kwahada for sale to New Mexico Comancheros. In October, 1871 a raid led by Quanah Parker stole seventy horses from the army at Rock Station. The commanding officer, Colonel Ranald S. Mackenzie, did not take this lightly. For the next two years, Mackenzie and his black cavalry troopers ranged the Staked Plains chasing the Kwahada. The campaign ended with an attack on a Comanche village at McClellan Creek (September, 1872). Mackenzie captured 130 women and children and held them hostage at Fort Concho. This slowed the raiding while the Comanches negotiated for their release. In April, 1873 they were released and sent under escort to Fort Sill. A detour had to be made around Jacksboro to prevent a riot. At the request of the Secretary of the Interior, Texas Governor Edmund J. Davis paroled the Kiowa chiefs in October after they had served only two years on the condition that the raiding stop. The Kiowa were grateful, but an occasional war party still slipped off the reservation, crossed the Red River, and headed south into Texas.

Buffalo hunting

Meanwhile, the great slaughter of the plains buffalo had begun. Between 1865 and 1875, the number of buffalo on the Great Plains fell from fifteen million to less than one million. Unofficially sanctioned by army commanders who issued free ammunition to hunters, it destroyed the basis for the plains tribes' way of life. During the winter of 1873–74, Cheyenne hunters returned to the Darlington agency to report that Kansas buffalo hunters were destroying the southern buffalo herds. As this news spread, violence erupted at the Darlington and Wichita agencies, which had to be put down by troops. Afterwards, large groups of Cheyenne left the reservation and headed for the plains. At first the Comanches and Kiowa thought the Cheyenne were mistaken, but their story of the plains littered with dead buffalo was eventually confirmed.

Second Battle of Adobe Walls

In December, the government decided to deal harshly with the Kiowa and Comanches to end the raids in Texas. The agent at Fort Sill was ordered to limit rations and suspend the distribution of ammunition. A sense of general panic set in, and by May several groups of Comanches and Kiowa had left the reservation. At first they were uncertain what to do. Several Comanches had recently been killed in Texas by Tonkawa scouts, and some of the first thoughts were of revenge. However, the agent had learned of their departure and purpose and had alerted the army.

After some discussion, a decision was made to attack the buffalo hunters on the Staked Plains. In June, 1874 a large Comanche-Cheyenne war party attacked twenty-three buffalo hunters camped in the Texas Panhandle at the site of Carson's 1864 battle at Adobe Walls. The Second Battle of Adobe Walls marked the beginning of the Buffalo War (or Red River War) (1874–75), the last great Indian war on the southern plains. After the initial rush failed, the Comanches came under fire from the hunters' long-range buffalo guns and were forced to retire. The uprising spread rapidly as more warriors left the agencies and joined the hostiles on the Staked Plains. To halt this, soldiers began to disarm the Comanches and Kiowa who had remained on the agencies. In August, groups of Penateka were peacefully drawing rations at the Wichita agency when soldiers stationed at the agency demanded they surrender their weapons. When this was refused, a fight broke out and the Comanches fled, but the agency was under siege for the next two days until it was relieved by troops from Fort Sill.

By September only 500 Kiowa and Comanche were still on the reservation; the others were out on the Staked Plains. That same month the army began to move. Three converging columns moved into the heart of the Staked Plains. Trapped between them, the Comanches, Kiowa, and Cheyenne had little rest. Colonel Nelson A. Miles' column made the first contact and defeated a group of Cheyenne near McClellan Creek. For the Comanches, Cheyenne, and Kiowa, the major blow occurred when Mackenzie located a mixed camp hidden in Palo Duro Canyon (September 26–27). After driving off the warriors during a short battle on September 28, he burned the camp and killed 2,000 captured horses.

There were few other encounters, but the relentless pressure and pursuit throughout the fall and winter had its effect. Starving, the remaining Comanches, Kiowa, and Cheyenne began to return to the agencies, mostly on foot because they had been forced to eat their horses. By December there were 900 on the Fort Sill reservation. In April, 200 Kwahada, who had never submitted, surrendered at Fort Sill. In June the last 400 Kwahada, including Isatai'i and Quanah Parker, surrendered. The war was over. Mackenzie disposed of many of the Comanche and Kiowa horses. After giving 100 to his Tonkawa scouts, he sold 1,600 horses and mules for $22,000. The proceeds were used to buy sheep and goats for his former enemies.

By 1879, the buffalo were gone. That year, the Kiowa-Comanche and Wichita agencies were merged into a single agency. Always pragmatic, the Comanches adjusted, but in typical Comanche style. Taking advantage of his Texas heritage, Quanah Parker emerged as an important Comanche leader. He collected tolls on cattle herds that used the Chisholm Trail to cross the reservation and sold grazing rights to nearby Texas ranchers. Few argued with him about price. With his five wives he moved into a large comfortable house, called the "Star House." It had eight large stars painted on the roof to insure he had more stars than any U.S. army general. He was elected a sheriff and served as a tribal judge. By the time he rode in Theodore Roosevelt's inaugural parade in 1905, Quanah had amassed 100 horses, 1,000 cattle, and 250 acres (1.0 km2) of cultivated farmland.

References

- Hamalainen, Pekka (2008). The Comanche Empire. Yale University Press. pp. 18–23. ISBN 978-0-300-12654-9.

- Comanche Nation

- Governor Cuervo y Valdez Report, 18 Aug 1706

- Bright, William, ed. (2004). Native American Placenames of the United States. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Hamalainen, pp. 102, 339

- "Comanche History," , accessed 3 Jan 2019.

- Robinson, Sherry. I Fought a Good Fight: A History of the Lipan Apaches (p. 56). University of North Texas Press.

- Adams, David B. Ëmbattled Borderland: Northern Nuevo León and the Indios Bárbaros, 1686-1870" The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 93, No. 2 (Oct 1991), pp 205-220

- Hamalainen, Pekka, The Comanche Empire. New Haven: Yale U Press, 2009, p. 232

- Adams, David B. (Oct 1992), "Embattled Borderland: Northern Nuevo León and the Indios Bárbaros, 1686-1870," The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, Vol. 95, No. 2 p. 220

- Kavanagh, Thomas W., Comanche Political History, U. Nebraska Press, Lincoln, 1996.

External links

See also Comanche#References

- Comanche Lodge - Dedicated to the Comanche Indians

- Kiowa Comanche Apache Indian Territory Project

- Maverick, Mary A. Description of The Council House Fight, 1896.

- McLeod, Hugh. Report on the Council House Fight, March 20, 1840