Conrad Baker

Conrad Baker (February 12, 1817 – April 28, 1885) was a state representative, 15th Lieutenant Governor, and the 15th Governor of the U.S. state of Indiana from 1867 to 1873. Baker had served in the Union Army during the American Civil War, rising to the rank of colonel but resigned following his election as lieutenant governor, during which time he played an important role in overseeing the formation and training of states levies. He served as acting-governor for five months during the illness of Governor Oliver Morton, and was elevated to Governor following Morton's resignation from office. During Baker's full term as governor, he focused primitively on the creation and improvement of institutions to help veterans and their families that had been disaffected by the war. He also championed the post-war federal constitutional amendments, and was able to successfully advocate their acceptance.

Conrad Baker | |

|---|---|

Conrad Baker from Who-When-What Book, 1900 | |

| Indiana House of Representatives | |

| In office December 5, 1845 – December 4, 1846 | |

| 15th Lieutenant Governor of Indiana | |

| In office January 9, 1865 – January 24, 1867 | |

| Governor | Oliver P. Morton |

| Preceded by | John R. Cravens as Acting Lieutenant Governor |

| Succeeded by | William Cumback |

| 15th Governor of Indiana | |

| In office January 24, 1867 – January 13, 1873 | |

| Lieutenant | Will Cumback |

| Preceded by | Oliver P. Morton |

| Succeeded by | Thomas A. Hendricks |

| Personal details | |

| Born | February 12, 1817 Franklin County, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Died | April 28, 1885 (aged 68) Evansville, Indiana, USA |

| Political party | Republican |

| Occupation | Lawyer, politician |

Early life

Family and background

Conrad Baker was born in Franklin County, Pennsylvania, on February 12, 1817, the son of Conrad Baker, a Presbyterian minister, and Mary Winternheimer Baker. He worked on the family farm until age fifteen and attended common school. He then enrolled in Pennsylvania College in Gettysburg where he studied law, but quit before graduating. He continued to study law in the office of Thaddeus Stevens. He met Matilda Escon Sommers and the couple married in 1838. They had two children. Baker was admitted to the bar in 1839 and opened his own office in Gettysburg.[1]

Early political career

Bakers closed his practice in 1841, and moved his family west to settle in Evansville, Indiana. He opened a new law office there, and took an interest in the city's civics. In 1845 he ran as the Whig candidate for representative of Vanderburgh County in the Indiana House of Representatives. He served one one-year term before returning to his practice. He was elected to serve on a county court in 1852 but resigned in 1854. His brother, William Baker, had also become active in the local politics, and served four terms as major of Evansville during the same time period.[2]

Baker was outspokenly anti-slavery, and following the break-up of the Whig party, he joined the newly formed Republican Party in 1854. At the state convention in 1856, he was nominated to run as lieutenant governor on the ticket with Oliver Morton a governor. The election was one of the most divisive in state history, with both sides making scathing attacks on the other. Despite the party's merger with several other third parties, the Republicans lost the election and Baker returned to his law practice in Evansville.[2]

American Civil War

Baker's wife, Matilda died in 1855, and Baker remarried in 1858 to Charlotte Frances Chute. The couple had two daughters and one son. He was in Evansville when the American Civil War began, and was part of a large crowd that gathered to discuss the event. He took the podium and delivered a speech calling on the crowd to take an oath of allegiance to the Union, which was administered by his brother, the Mayor. He then called on all the able-bodied men to follow him to war. Baker and his brother began actively recruiting a full regiment of men to serve in the war, and he was promoted to serve as Colonel of the 1st Regiment Indiana Cavalry.[3]

Baker led his regiment in defensive and garrison duty across the western theater of the war, and remained in regular communication with Governor Oliver Morton, who has become governor a few months earlier. Baker was most involved in coordinating supplies, and became a valuable organizer. Morton soon promoted him to serve as provost marshal of the state, and ordered him to return to Indianapolis to oversee operations. There he oversaw the formation of dozens of state regiments, tens of thousand of men, the shipment of tons of supplies, the distributions of weapons, and the management of the state arsenal.[3]

Governor

Acting

Baker left the army in 1864 to run again as Lieutenant Governor on the ticket with Oliver Morton and was elected with a 20,000-vote majority. Morton took a period of poor health in 1865 after suffering a paralytic stroke. He continued his duties briefly, but decided to attempt to seek a cure to the paralysis. He left the state and left Baker to serve as acting governor for five months until his health recovered. When Morton was elected to the Senate in 1866, Baker succeeded him as governor. While completing Morton's term, he began to advocate school reform. His primary goal was to improve the quality of teachers, which he sought to do by creating incentives to encourage teachers to consider their job as a permanent career. At that time, teaching was considered a temporary position by most teachers, until they could find a superior job elsewhere. The General Assembly accepted his plan and passed legislation to enact it.[3]

Second term

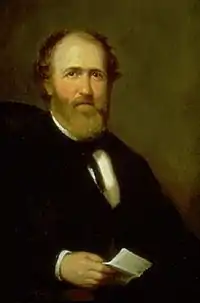

In 1868, Baker was reelected to the position of governor, defeating Thomas Hendricks by 961 votes, the closest in state history. During his administration, a women's prison was built, and a soldiers' home to assist the returning veterans and the Indiana State Normal School in Terre Haute were constructed. Other school institutions were built during his term using federal funding provided by the land-grant system. Along with private donations, the money was used to start Purdue University. Baker signed the law to create the school in 1869, and it opened just after his term ended.[4] Another of Baker's acts as governor was to establish the governor's portrait collection. The assembly agreed to spend up to $200 per portrait for the creation of the collection. Baker then hired painters and sought out the families of the former governors to procure photos and paintings from which official portraits could be created.[5]

Baker's most difficult goal to achieve was the ratification of the post-war amendments that, among other things, banned slavery and granted blacks the right to vote. His advocacy on the issues though managed to secure each of their ratifications, with the fourteenth amendment being the last ratified in 1869. The Democrats had resigned office en masse when the bill was put up for a vote to deny quorum, but the Republicans went ahead to approve the amendment. When the Democrats took the legislature in the following election, they revoked the ratification of the amendments, but it was too late and the federal government, which was Republican-dominated at the time, had already added them to the constitution.[6]

Baker also advocated for African American rights through additional school reform. In 1869 he signed legislation which addressed an 1865 school law which prevented the establishment of public schools for non-white children. The new law extended current public school funding to establish schools for African Americans and repealed all laws inconsistent herewith.[7]

Death and legacy

After Baker's term as governor expired he retired from public office and reopened his law office. His new partner was his former political opponent, Thomas Hendricks. After Hendricks was elected governor in 1872, Baker took on state attorney general Oscar B. Hord and Chief Justice of the Indiana Supreme Court Samuel Perkins as partners. The law firm was passed on to Baker's son, and has since become one of the leading law firms in the United States, Baker & Daniels LLP.

Baker remained active in public affairs and urged the state schools to grant equal opportunities. He became fairly active in the woman's suffrage movement and delivered an address to one of their meetings. He died on April 28, 1885, and was buried in Evansville, Indiana.[8][9]

See also

- List of Governors of Indiana

References

Notes

- Gugin, p. 152

- Gugin, p. 153

- Gugin, p. 154

- Gugin, p. 155

- Gugin, p. 158

- Gugin, p. 156

- Indiana. General Assembly, House of Representatives (1869). Journal of the House of Representatives of the state of Indiana, during the special session of the General Assembly, commencing Thursday, April 8, 1869. Indiana Memory Program Indiana State Library. Indianapolis : Alexander H. Conner, state printer, 1869.

- Sobel, Robert, and John Raimo, eds. Biographical Directory of the Governors of the United States, 1789-1978, Vol. 1, Westport, Conn.; Meckler Books, 1978. 4 vols

- Gugin, p. 159

Bibliography

- Gugin, Linda C.; St. Clair, James E, eds. (2006). The Governors of Indiana. Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society Press. ISBN 0-87195-196-7.

- Mueller, Arnold Ernst R., "Conrad Baker, Former Governor of Indiana" (1944). Graduate Thesis Collection. 412. https://digitalcommons.butler.edu/grtheses/412.

External links

- Biography and portrait from the Indiana Historical Bureau

- National Association of Governors

- Conrad Baker at FindAGrave

| Party political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Oliver P. Morton |

Republican nominee for Governor of Indiana 1868 |

Succeeded by Thomas M. Browne |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Oliver P. Morton |

Lieutenant Governor of Indiana 1865 – 1867 |

Succeeded by William Cumback |

| Preceded by Oliver P. Morton |

Governor of Indiana January 24, 1867– January 13, 1873 |

Succeeded by Thomas A. Hendricks |