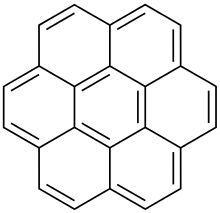

Coronene

Coronene (also known as superbenzene) is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) comprising seven peri-fused benzene rings.[8] Its chemical formula is C

24H

12. It is a yellow material that dissolves in common solvents including benzene, toluene, and dichloromethane. Its solutions emit blue light fluorescence under UV light. It has been used as a solvent probe, similar to pyrene.

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Coronene[1] | |

| Other names

[6]circulene X1001757-9, superbenzene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| 658468 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.348 |

| EC Number |

|

| 286459 | |

| KEGG | |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C24H12 | |

| Molar mass | 300.360 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white or pale yellow powder[2] |

| Density | 1.371 g/cm3[3] |

| Melting point | 437.3 °C (819.1 °F; 710.5 K) [3] |

| Boiling point | 525 °C (977 °F; 798 K) [3] |

| 0.14 μg/L[4] | |

| Solubility | Very soluble: benzene, toluene, hexane,[5] Chloroform (1 mmol·L−1)[6] and ethers, sparingly soluble in ethanol. |

| -243.3·10−6 cm3/mol | |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic | |

| P21/n[7] | |

| D6h | |

a = 10.02 Å, b = 4.67 Å, c = 15.60 Å α = 90°, β = 106.7°, γ = 90° | |

Formula units (Z) |

2 |

| 0 D | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | flammable[2] |

| GHS pictograms |  |

| GHS Signal word | Warning |

| H371 | |

| P260, P264, P270, P309+311, P405, P501 | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

The compound is of theoretical interest to organic chemists because of its aromaticity. It can be described by 20 resonance structures or by a set of three mobile Clar sextets. In the Clar sextet case, the most stable structure for coronene has only the three isolated outer sextets as fully aromatic although superaromaticity would still be possible when these sextets are able to migrate into the next ring.

Occurrence and synthesis

Coronene occurs naturally as the very rare mineral carpathite, which is characterized by flakes of pure coronene embedded in sedimentary rock. This mineral may be created from ancient hydrothermal vent activity.[9] In earlier times this mineral was also called karpatite or pendletonite.[10]

The presence of coronene putatively formed from contact of magma with fossil fuel deposits has been used to argue that the Permian-Triassic “Great Dying” event was caused by a greenhouse gas warming episode triggered by large-scale Siberian vulcanism. [11]

Coronene is produced in the petroleum-refining process of hydrocracking, where it can dimerize to a fifteen ring PAH, trivially named "dicoronylene" (formally named benzo[10,11]phenanthro[2',3',4',5',6':4,5,6,7]chryseno[1,2,3-bc]coronene or benzo[1,2,3-bc:4,5,6-b'c']dicoronene). Centimeter-long crystals can be grown from a supersaturated solution of the molecules in toluene (ca. 2.5 mg/ml), which is slowly cooled (ca. 0.04 K/min) from 328 K to 298 K over a period of 12 hours.[7]

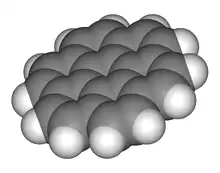

Structure

Coronene is a planar circulene. It forms needle-like crystals with a monoclinic, herringbone-like structure. The most common polymorph is γ, but β form can also be produced in an applied magnetic field (ca. 1 Tesla)[7] or by phase transition from γ decreasing the temperature below 158 K.[12]

Crystals of β and γ coronene under daylight (left) and UV light (right).[7]

Crystals of β and γ coronene under daylight (left) and UV light (right).[7]

Other uses

Coronene has been used in the synthesis of graphene. For example, coronene molecules evaporated onto a copper surface at 1000 degrees Celsius will form a graphene lattice which can then be transferred onto another substrate.[13]

See also

- Cyclooctadecanonaene, the compound consisting of just the outer ring without the benzene core

- Hexa-peri-hexabenzocoronene and hexa-cata-hexabenzocoronene, consisting of additional benzene rings fused around the periphery

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coronene. |

- Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry : IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013 (Blue Book). Cambridge: The Royal Society of Chemistry. 2014. p. 206. doi:10.1039/9781849733069-FP001. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- Coronene (EINECS NO. 205-881-7). guidechem.com

- Haynes, William M., ed. (2011). CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics (92nd ed.). Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. p. 3.128. ISBN 1439855110.

- Mackay, D.; Shiu, W. Y. (1977). "Aqueous solubility of polynuclear aromatic hydrocarbons". Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 22 (4): 399. doi:10.1021/je60075a012.

- Bertarelli, Chiara. Molecules for organic electronics: intermolecular interactions vs properties. Dipartimento di Chimica, Politecnico di Milano

- Wang, Chen; Wang, Jianlin; Wu, Na; Xu, Miao; Yang, Xiaomei; Lu, Yalin; Zang, Ling (2017). "Donor–acceptor single cocrystal of coronene and perylene diimide: molecular self-assembly and charge-transfer photoluminescence". RSC Adv. 7 (4): 2382–2387. doi:10.1039/C6RA25447K.

- Potticary, Jason; Terry, Lui R.; Bell, Christopher; Papanikolopoulos, Alexandros N.; Christianen, Peter C. M.; Engelkamp, Hans; Collins, Andrew M.; Fontanesi, Claudio; Kociok-Köhn, Gabriele; Crampin, Simon; Da Como, Enrico; Hall, Simon R. (2016). "An unforeseen polymorph of coronene by the application of magnetic fields during crystal growth". Nature Communications. 7: 11555. doi:10.1038/ncomms11555. PMC 4866376. PMID 27161600.

- Fetzer, J. C. (2000). The Chemistry and Analysis of the Large Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons. New York: Wiley.

- Karpatite. luminousminerals.com

- Carpathite. mindat.org

- Kaiho, Kunio; Aftabuzzaman, Md.; Jones, David S.; Tian, Li (2020). "Pulsed volcanic combustion events coincident with the end-Permian terrestrial disturbance and the following global crisis". Geology. doi:10.1130/G48022.1.

- Salzillo, Tommaso; Giunchi, Andrea; Masino, Matteo; Bedoya-Martínez, Natalia; Della Valle, Raffaele Guido; Brillante, Aldo; Girlando, Alberto; Venuti, Elisabetta (2018). "An Alternative Strategy to Polymorph Recognition at Work: The Emblematic Case of Coronene". Crystal Growth & Design. 18 (9): 4869–4873. doi:10.1021/acs.cgd.8b00934.

- Wan, Xi; et al. (2013). "Enhanced Performance and Fermi-Level Estimation of Coronene-Derived Graphene Transistors on Self-Assembled Monolayer Modified Substrates in Large Areas". The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. ACS Publications. 117 (9): 4800–4807. doi:10.1021/jp309549z.