Corruption in India

Corruption in India is an issue which affects the economy of central, state and local government agencies in many ways. Corruption is blamed for stunting the economy of India.[1] A study conducted by Transparency International in 2005 recorded that more than 62% of Indians had at some point or another paid a bribe to a public official to get a job done.[2][3] In 2008, another report showed that about 50% of Indians had first hand experience of paying bribes or using contacts to get services performed by public offices, however, in 2019 their Corruption Perceptions Index ranked the country 80th place out of 180, reflecting steady decline in perception of corruption among people.[4][5]

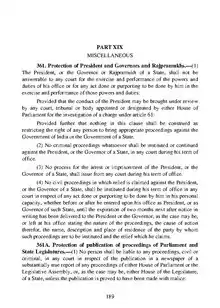

.png.webp)

|

>80

70–79

60–69

50–59 |

40–49

30–39

20–29

10–19 |

<10

Data unavailable |

| Political corruption | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concepts | ||||||||||||

| Corruption by country | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

The largest contributors to corruption are entitlement programs and social spending schemes enacted by the Indian government. Examples include the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act and the National Rural Health Mission.[6][7] Other areas of corruption include India's trucking industry which is forced to pay billions of rupees in bribes annually to numerous regulatory and police stops on interstate highways.[8]

The media has widely published allegations of corrupt Indian citizens stashing millions of rupees in Swiss banks. Swiss authorities denied these allegations, which were later proven in 2015–2016.[9][10]

The causes of corruption in India include excessive regulations, complicated tax and licensing systems, numerous government departments with opaque bureaucracy and discretionary powers, monopoly of government controlled institutions on certain goods and services delivery, and the lack of transparent laws and processes.[11][12] There are significant variations in the level of corruption and in the government's efforts to reduce corruption across different areas of India.

Politics

Corruption in India is a problem that has serious implications for protecting the rule of law and ensuring access to justice. As of December 2009, 120 of India's 542 parliament members were accused of various crimes, under India's First Information Report procedure wherein anyone can allege another to have committed a crime.[13]

Many of the biggest scandals since 2010 have involved high level government officials, including Cabinet Ministers and Chief Ministers, such as the 2010 Commonwealth Games scam (₹70,000 crore (US$9.8 billion)), the Adarsh Housing Society scam, the Coal Mining Scam (₹1.86 lakh crore (US$26 billion)), the Mining Scandal in Karnataka and the Cash for Vote scams.

Bureaucracy

Bribery

A 2005 study done by the Transparency International in India found that more than 92% of the people had firsthand experience of paying bribes or peddling influence to get services performed in a public office.[3] Taxes and bribes are common between state borders; Transparency International estimates that truckers annually pay ₹222 crore (US$31 million) in bribes.[8][14]

Both government regulators and police share in bribe money, to the tune of 43% and 45% each, respectively. The en route stoppages at checkpoints and entry-points can take up to 11 hours per day. About 60% of these (forced) stoppages on roads by concerned authorities such as government regulators, police, forest, sales and excise, octroi, and weighing and measuring departments are for extorting money. The loss in productivity due to these stoppages is an important national concern; the number of truck trips could increase by 40%, if forced delays are avoided. According to a 2007 World Bank published report, the travel time for a Delhi-Mumbai trip could be reduced by about 2 days per trip if the corruption and associated regulatory stoppages to extract bribes were eliminated.[14][15][16]

A 2009 survey of the leading economies of Asia, revealed Indian bureaucracy to be not only the least efficient among Singapore, Hong Kong, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, Malaysia, Taiwan, Vietnam, China, Philippines and Indonesia, but that working with India's civil servants was a "slow and painful" process.[17]

Land and property

Officials are alleged to steal state property. In cities and villages throughout India, groups of municipal and other government officials, elected politicians, judicial officers, real estate developers and law enforcement officials, acquire, develop and sell land in illegal ways.[18] Such officials and politicians are very well protected by the immense power and influence they possess. Apart from this, slum-dwellers who are allotted houses under several housing schemes such as Pradhan Mantri Gramin Awaas Yojana, Rajiv Awas Yojna, Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna etc., rent out these houses to others, to earn money due to severe unemployment and lack of a steady source of income.

Tendering processes and awarding contracts

A 2006 report claimed state-funded construction activities in Uttar Pradesh, such as road building were dominated by construction mafias, consisting of cabals of corrupt public works officials, materials suppliers, politicians and construction contractors.[19]

Problems caused by corruption in government funded projects are not limited to the state of Uttar Pradesh. According to The World Bank, aid programmes are beset by corruption, bad administration and under-payments. As an example, the report cites that only 40% of grain handed out for the poor reaches its intended target. The World Bank study finds that the public distribution programmes and social spending contracts have proven to be a waste due to corruption.[20]

For example, the government implemented the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) on 25 August 2005. The Central government outlay for this welfare scheme is ₹400 crore (US$56 million) in FY 2010–2011.[21] After 5 years of implementation, in 2011, the programme was widely criticised as no more effective than other poverty reduction programmes in India. Despite its best intentions, MGNREGA faces the challenges of corrupt officials reportedly pocketing money on behalf of fake rural employees, poor quality of the programme infrastructure, and unintended destructive effect on poverty.[7][22]

Hospitals and health care

In government hospitals, corruption is associated with non-availability/duplication of medicines, obtaining admission, consultations with doctors and receiving diagnostic services.[3]

National Rural Health Mission is another health care-related government programme that has been subject to large scale corruption allegations. This social spending and entitlement programme hoped to improve health care delivery across rural India. Managed since 2005 by the Ministry of Health, the Indian government mandated a spending of ₹2.77 lakh crore (US$39 billion) in 2004–2005, and increased it annually to be about 1% of India's gross domestic product. The National Rural Health Mission programme has been clouded by a large-scale corruption scandal in which high-level government appointed officials were arrested, several of whom died under mysterious circumstances including one in prison. Corruption, waste and fraud-related losses from this government programme has been alleged to be ₹1 lakh crore (US$14 billion).[23][24][25][6]

Science and technology

CSIR, the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, has been flagged in ongoing efforts to root out corruption in India.[26] Established with the directive to do translational research and create real technologies, CSIR has been accused of transforming into a ritualistic, overly-bureaucratic organisation that does little more than churn out papers.[27][28]

There are many issues facing Indian scientists, with some, such as MIT systems scientist VA Shiva Ayyadurai, calling for transparency, a meritocratic system, and an overhaul of the bureaucratic agencies that oversee science and technology.[29][30][31] Sumit Bhaduri stated, "The challenges of turning Indian science into part of an innovation process are many. Many competent Indian scientists aspire to be ineffectual administrators (due to administrative power and political patronage), rather than do the kind of science that makes a difference".[32] Prime minister Manmohan Singh spoke at the 99th Indian Science Congress and commented on the state of the sciences in India, after an advisory council informed him there were problems with "the overall environment for innovation and creative work" and a "war-like" approach was needed.[33]

Income tax department

There have been several cases of collusion involving officials of the Income Tax Department of India for preferential tax treatment and relaxed prosecutions in exchange for bribes.[34][35]

Preferential award of mineral resources

In August 2011, an iron ore mining scandal became a media focus in India. In September 2011, elected member of Karnataka's legislative assembly Janardhana Reddy, was arrested on charges of corruption and illegal mining of iron ore in his home state. It was alleged that his company received preferential allotment of resources, organised and exported billions of dollars' worth of iron ore to Chinese companies in recent years without paying any royalty to the state government exchequer of Karnataka or the central government of India, and that these Chinese companies made payment to shell companies registered in Caribbean and north Atlantic tax havens controlled by Reddy.[36][37]

It was also alleged that corrupt government officials cooperated with Reddy, starting from government officials in charge of regulating mining to government officials in charge of regulating port facilities and shipping. These officials received monthly bribes in exchange for enabling the illegal export of illegally mined iron ore to China. Such scandals have led to a demand in India for consensually driven action plan to eradicate the piracy of India's mineral resources by an illegal, politically corrupt government officials-business nexus, removal of incentives for illegal mining, and the creation of incentives for legal mining and domestic use of iron ore and steel manufacturing.[36][37]

Driver licensing

A study conducted between 2004 and 2005 found that India's driver licensing procedure was a hugely distorted bureaucratic process and allows drivers to be licensed despite their low driving ability through promoting the usage of agents. Individuals with the willingness to pay make a significant payment above the official fee and most of these extra payments are made to agents, who act as an intermediary between bureaucrats and applicants.[38]

The average licensee paid Rs 1,080, approximately 2.5 times the official fee of Rs 450, in order to obtain a license. On average, those who hired agents had a lower driving ability, with agents helping unqualified drivers obtain licenses and bypass the legally required driving examination. Among the surveyed individuals, approximately 60% of the license holders did not even take the licensing exam and 54% of those license holders failed an independent driving test.[39]

Agents are the channels of corruption in this bureaucratic driver licensing system, facilitating access to licenses among those who are unqualified to drive. Some of the failures of this licensing system are caused by corrupt bureaucrats who collaborate with agents by creating additional barriers within the system against those who did not hire agents.[38]

Trends

Professor Bibek Debroy and Laveesh Bhandari claim in their book Corruption in India: The DNA and RNA that public officials in India may be cornering as much as ₹921 billion (US$13 billion), or 5 per cent of the GDP through corruption.[15] The book claims most bribery is in government delivered services and the transport and real estate industries.

Bribery and corruption are pervasive, but some areas tend to more issues than others. A 2013 EY (Ernst & Young) Study[40] reports the industries perceived to be the most vulnerable to corruption as: Infrastructure & Real Estate, Metals & Mining, Aerospace & Defence, and Power & Utilities. There are a range of specific factors that make a sector more susceptible to bribery and corruption risks than others. High use of middlemen, large value contracts, and liasoning activities etc. drive the depth, volume and frequency of corrupt practices in vulnerable sectors.

A 2011 KPMG study reports India's real estate, telecommunications and government-run social development projects as the three top sectors plagued by corruption. The study found India's defence, the information technology industry and energy sectors to be the most competitive and least corruption prone sectors.[11]

CMS India claims in its 2010 India Corruption Study report that socio-economically weaker sections of Indian society are the most adversely affected by government corruption. These include the rural and urban poor, although the study claims that nationwide perception of corruption has decreased between 2005 and 2010. Over the 5-year period, a significantly greater number of people surveyed from the middle and poorest classes in all parts of India claimed government corruption had dropped over time, and that they had fewer direct experiences with bribery demands.[41]

The table below compares the perceived anti-corruption effort across some of the major states in India.[12] A rising index implies higher anti-corruption effort and falling corruption. According to this table, the states of Bihar and Gujarat have experienced significant improvements in their anti-corruption efforts, while conditions have worsened in the states of Assam and West Bengal. Consistent with the results in this table, in 2012 a BBC News report claimed the state of Bihar has transformed in recent years to become the least corrupt state in India.[42]

| State | 1990–95 | 1996–00 | 2001–05 | 2006–10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bihar | 0.41 | 0.30 | 0.43 | 0.88 |

| Gujarat | 0.48 | 0.57 | 0.64 | 0.69 |

| Andhra Pradesh | 0.53 | 0.73 | 0.55 | 0.61 |

| Punjab | 0.32 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.60 |

| Jammu & Kashmir | 0.13 | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.40 |

| Haryana | 0.33 | 0.60 | 0.31 | 0.37 |

| Himachal Pradesh | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 0.35 |

| Tamil Nadu | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.24 | 0.29 |

| Madhya Pradesh | 0.23 | 0.22 | 0.31 | 0.29 |

| Karnataka | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.29 |

| Rajasthan | 0.27 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.27 |

| Kerala | 0.16 | 0.20 | 0.22 | 0.27 |

| Maharashtra | 0.45 | 0.29 | 0.27 | 0.26 |

| Uttar Pradesh | 0.11 | 0.11 | 0.16 | 0.21 |

| Odisha | 0.22 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.19 |

| Assam | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.17 |

| West Bengal | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.03 | 0.01 |

Black money

Black money refers to money that is not fully or legitimately the property of the 'owner'. A government white paper on black money in India suggests two possible sources of black money in India;[9] the first includes activities not permitted by the law, such as crime, drug trade, terrorism and corruption, all of which are illegal in India and secondly, wealth that may have been generated through lawful activity but accumulated by failure to declare income and pay taxes. Some of this black money ends up in illicit financial flows across international borders, such as deposits in tax haven countries.

A November 2010 report from the Washington-based Global Financial Integrity estimates that over a 60-year period, India lost US$213 billion in illicit financial flows beginning in 1948; adjusted for inflation, this is estimated to be $462 billion in 2010, or about $8 billion per year ($7 per capita per year). The report also estimated the size of India's underground economy at approximately US$640 billion at the end of 2008 or roughly 50% of the nation's GDP.[43]

Indian black money in Switzerland

India was ranked 38th by money held by its citizens in Swiss banks in 2004 but then improved its ranking by slipping to 61st position in 2015 and further improved its position by slipping to 75th position in 2016.[44][45] According to a 2010 The Hindu article, unofficial estimates indicate that Indians had over US$1,456 billion in black money stored in Swiss banks (approximately US$1.4 trillion).[46] While some news reports claimed that data provided by the Swiss Banking Association[47] Report (2006) showed India has more black money than the rest of the world combined,[48][49] a more recent report quoted the SBA's Head of International Communications as saying that no such official Swiss Banking Association statistics exist.[50]

Another report said that Indian-owned Swiss bank account assets are worth 13 times the country's national debt. These allegations have been denied by Swiss Bankers Association. James Nason of Swiss Bankers Association in an interview about alleged black money from India, holds that "The (black money) figures were rapidly picked up in the Indian media and in Indian opposition circles, and circulated as gospel truth. However, this story was a complete fabrication. The Swiss Bankers Association never published such a report. Anyone claiming to have such figures (for India) should be forced to identify their source and explain the methodology used to produce them."[10][51]

In a separate study, Dev Kar of Global Financial Integrity concludes, "Media reports circulating in India that Indian nationals held around US$1.4 trillion in illicit external assets are widely off the mark compared to the estimates found by his study." Kar claims the amounts are significantly smaller, only about 1.5% of India's GDP on average per annum basis, between 1948 and 2008. This includes corruption, bribery and kickbacks, criminal activities, trade mispricing and efforts to shelter wealth by Indians from India's tax authorities.[43]

According to a third report, published in May 2012, Swiss National Bank estimates that the total amount of deposits in all Swiss banks, at the end of 2010, by citizens of India were CHF 1.95 billion (₹92.95 billion (US$1.3 billion)). The Swiss Ministry of External Affairs has confirmed these figures upon request for information by the Indian Ministry of External Affairs. This amount is about 700-fold less than the alleged $1.4 trillion in some media reports.[9] The report also provided a comparison of the deposits held by Indians and by citizens of other nations in Swiss banks. Total deposits held by citizens of India constitute only 0.13 per cent of the total bank deposits of citizens of all countries. Further, the share of Indians in the total bank deposits of citizens of all countries in Swiss banks has reduced from 0.29 per cent in 2006 to 0.13 per cent in 2010.

Domestic black money

Indian companies are reportedly misusing public trusts for money laundering. India has no centralised repository—like the registrar of companies for corporates—of information on public trusts.[52]

2016 Evasion attempts after note ban

- Gold purchases

In Gujarat, Delhi and many other major cities, sales of gold increased on 9 November, with an increased 20% to 30% premium surging the price as much as ₹45,000 (US$630) from the ruling price of ₹31,900 (US$450) per 10 grams (0.35 oz).[53][54]

- Donations

Authorities of Sri Jalakanteswarar temple at Vellore discovered cash worth ₹4.4 million (US$62,000) from the temple Hundi.[55]

- Multiple bank transactions

There have also been reports of people circumventing the restrictions imposed on exchange transactions and attempting to convert black money into white by making multiple transactions at different bank branches.[56] People were also getting rid of large amounts of banned currency by sending people in groups to exchange their money at banks.[57] In response, the government announced that it would start marking customers with indelible ink. This was in addition to other measures proposed to ensure that the exchange transactions are carried out only once by each person.[58][59][60] On 17 November, the government reduced the exchange amount to ₹2,000 (US$28) to discourage attempts to convert black money into legitimate money.

- Railway bookings

As soon as the demonetisation was announced, it was observed by the Indian Railways authorities that a large number of people started booking tickets particularly in classes 1A and 2A for the longest distance possible, to get rid of unaccounted for cash. A senior official said, "On November 13, 42.7 million passengers were nationally booked across all classes. Of these, only 1,209 were 1A and 16,999 for 2A. It is a sharp dip from the number of passengers booked on November 9, when 27,237 passengers had booked tickets in 1A and 69,950 in 2A."[61] The Railways Ministry and the Railway Board responded swiftly and decided that cancellation and refund of tickets of value ₹10,000 and above will not be allowed by any means involving cash. The payment can only be through cheque/electronic payment. Tickets above ₹10,000 can be refunded by filing ticket deposit receipt only on surrendering the original ticket. A copy of the PAN card must be submitted for any cash transaction above ₹50,000. The railway claimed that since the Railway Board on 10 November imposed a number of restrictions to book and cancel tickets, the number of people booking 1A and 2A tickets came down.[61][62]

- Municipal and local tax payments

As the use of the demonetised notes had been allowed by the government for the payment of municipal and local body taxes, leading to people using the demonetised ₹500 and ₹1,000 notes to pay large amounts of outstanding and advance taxes. As a result, revenue collections of the local civic bodies jumped. The Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation reported collecting about ₹1.6 billion (US$22 million) in cash payments of outstanding and advance taxes within 4 days.[63]

- Axis Bank

Income Tax officials raided multiple branches of Axis Bank and found bank officials involved in acts of money laundering.[64][65][66]

Business and corruption

Public servants have very wide discretionary powers offering the opportunity to extort undue payments from companies and ordinary citizens. The awarding of public contracts is notoriously corrupt, especially at the state level. Scandals involving high-level politicians have highlighted the payment of kickbacks in the healthcare, IT and military sectors. The deterioration of the overall efficiency of the government, protection of property rights, ethics and corruption as well as undue influence on government and judicial decisions has resulted in a more difficult situation for business environment.

Judiciary

According to Transparency International, Judicial corruption in India is attributable to factors such as "delays in the disposal of cases, shortage of judges and complex procedures, all of which are exacerbated by a preponderance of new laws".[67] Over the years there have been numerous allegations against judges, and in 2011 Soumitra Sen, a former judge at the Kolkata High Court became the first judge in India to be impeached by the Rajya Sabha, (Upper House of the Indian Parliament) for misappropriation of funds.[68]

Anti-corruption efforts

Right to Information Act

The 2005 Right to Information Act required government officials to provide information requested by citizens or face punitive action, as well as the computerisation of services and the establishment of vigilance commissions. This has considerably reduced corruption and opened up avenues to redress grievances.[3]

Right to Public Services laws

Right to Public Services legislation, which has been enacted in 19 states of India, guarantee time bound delivery of services for various public services rendered by the government to citizen and provides mechanisms for punishing the errant public servant who is deficient in providing the service stipulated under the statute.[69] Right to Service legislation is meant to reduce corruption among the government officials and to increase transparency and public accountability.[70]

Anti-corruption laws in India

Public servants in India can be imprisoned for several years and penalised for corruption under the:

- Indian Penal Code, 1860

- Prosecution section of Income Tax Act, 1961

- The Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988

- The Benami Transactions (Prohibition) Act, 1988 to prohibit benami transactions.

- Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002

Punishment for bribery in India can range from six months to seven years of imprisonment.

India is also a signatory to the United Nations Convention against Corruption since 2005 (ratified 2011). The Convention covers a wide range of acts of corruption and also proposes certain preventive policies.[71]

The Lokpal and Lokayuktas Act, 2013 which came into force from 16 January 2014, seeks to provide for the establishment of the institution of Lokpal to inquire into allegations of corruption against certain public functionaries in India.[72][73]

Whistle Blowers Protection Act, 2011, which provides a mechanism to investigate alleged corruption and misuse of power by public servants and also protect anyone who exposes alleged wrongdoing in government bodies, projects and offices, has received the assent of the President of India on 9 May 2014, and (as of 2 August) is pending for notification by the Central Government.[74][75]

At present there are no legal provisions to check graft in the private sector in India. Government has proposed amendments in existing acts and certain new bills for checking corruption in private sector. Big-ticket corruption is mainly witnessed in the operations of large commercial or corporate entities. In order to prevent bribery on supply side, it is proposed that key managerial personnel of companies' and also the company shall be held liable for offering bribes to gain undue benefits.

The Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 provides that the properties of corrupt public servants shall be confiscated. However, the Government is considering incorporating provisions for confiscation or forfeiture of the property of corrupt public servants into the Prevention of Corruption Act, 1988 to make it more self-contained and comprehensive.[40]

A committee headed by the Chairman of Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT), has been constituted to examine ways to strengthen laws to curb generation of black money in India, its illegal transfer abroad, and its recovery. "The Committee shall examine the existing legal and administrative framework to deal with the menace of generation of black money through illegal means including inter-alia the following: 1. Declaring wealth generated illegally as national asset; 2. Enacting/amending laws to confiscate and recover such assets; and 3. Providing for exemplary punishment against its perpetrators." (Source: 2013 EY report on Bribery & Corruption)

The Companies Act, 2013, contains certain provisions to regulate frauds by corporations including increased penalties for frauds, giving more powers to the Serious Fraud Investigation Office, mandatory responsibility of auditors to reveal frauds, and increased responsibilities of independent directors.[76] The Companies Act, 2013 also provides for mandatory vigil mechanisms which allow directors and employees to report concerns and whistleblower protection mechanism for every listed company and any other companies which accepts deposits from public or has taken loans more than 50 crore rupees from banks and financial institutions. This intended to avoid accounting scandals such as the Satyam scandal which have plagued India.[77] It replaces The Companies Act, 1956 which was proven outmoded in terms of handling 21st century problems.[78]

In 2015, Parliament passed the Black Money (Undisclosed Foreign Income and Assets) and Imposition of Tax Bill, 2015 to curb and impose penalties on black money hoarded abroad. The Act has received the assent of the President of India on 26 May 2015. It came into effect from 1 July 2015.

Anti-corruption police and courts

The Directorate General of Income Tax Investigation, Central Vigilance Commission and Central Bureau of Investigation all deal with anti-corruption initiatives. Certain states such as Andhra Pradesh (Anti-Corruption Bureau, Andhra Pradesh) and Karnataka (Lokayukta) also have their own anti-corruption agencies and courts.[79][80]

Andhra Pradesh's Anti Corruption Bureau (ACB) has launched a large scale investigation in the "cash-for-bail" scam.[81] CBI court judge Talluri Pattabhirama Rao was arrested on 19 June 2012 for taking a bribe to grant bail to former Karnataka Minister Gali Janardhan Reddy, who was allegedly amassing assets disproportionate to his known sources of income. Investigation revealed that India Cements (one of India's largest cement companies) had been investing in Reddy's businesses in return for government contracts.[82] A case has also been opened against seven other individuals under the Indian Penal Code and the Prevention of Corruption Act.[81]

Civic anti-corruption organisations

A variety of organisations have been created in India to actively fight against corrupt government and business practices. Notable organisations include:

- [Bharat Swabhiman Trust], established by Ramdev, has campaigned against black money and corruption for a decade.

- 5th Pillar is most known for the creation of the zero rupee note, a valueless note designed to be given to corrupt officials when they request bribes.[83]

- India Against Corruption was a popular movement active during 2011–12 that received much media attention. Among its prominent public faces were Arvind Kejriwal, Kiran Bedi and Anna Hazare. Kejriwal went on to form the Aam Aadmi Party and Hazare established Jan Tantra Morcha.[84]

- Jaago Re! One Billion Votes was an organisation founded by Tata Tea and Janaagraha to increase youth voter registration.[85] They have since expanded their work to include other social issues, including corruption.[86]

- The Lok Satta Movement, has transformed itself from a civil organisation to a full-fledged political party, the Lok Satta Party. The party has fielded candidates in Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, and Bangalore. In 2009, it obtained its first elected post, when Jayaprakash Narayan won the election for the Kukatpally Assembly Constituency in Andhra Pradesh.

Electoral Reforms

A number of ideas have been in discussion to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of electoral processes in India.

Factors contributing to corruption in India

In a 2004 report on Corruption in India,[11] one of the world's largest audit and compliance firms KPMG notes several issues that encourage corruption in India. The report suggests high taxes and excessive regulation bureaucracy as a major cause; India has high marginal tax rates and numerous regulatory bodies with the power to stop any citizen or business from going about their daily affairs.[11][87]

This power of Indian authorities to search and question individuals creates opportunities for corrupt public officials to extract bribes—each individual or business decides if the effort required for due process and the cost of delay is worth paying the bribe demanded. In cases of high taxes, paying off the corrupt official is cheaper than the tax. This, according to the report, is one major cause of corruption in India and 150 other countries across the world. In the real estate industry, the high capital gains tax in India encourages large-scale corruption. The KPMG report claims that the correlation between high real estate taxes and corruption is high in India as it is other countries including the developed economies; this correlation has been true in modern times as well as throughout centuries of human history in various cultures.[11][87]

The desire to pay lower taxes than those demanded by the state explains the demand side of corruption. The net result is that the corrupt officials collect bribes, the government fails to collect taxes for its own budget, and corruption grows. The report suggests regulatory reforms, process simplification and lower taxes as means to increase tax receipts and reduce causes of corruption.[11][87]

In addition to tax rates and regulatory burdens, the KPMG report claims corruption results from opaque process and paperwork on the part of the government. Lack of transparency allows room for manoeuvre for both demanders and suppliers of corruption. Whenever objective standards and transparent processes are missing, and subjective opinion driven regulators and opaque/hidden processes are present, conditions are ripe for corruption.[11][88]

Vito Tanzi in an International Monetary Fund study suggests that in India, like other countries in the world, corruption is caused by excessive regulations and authorisation requirements, complicated taxes and licensing systems, mandated spending programmes, lack of competitive free markets, monopoly of certain goods and service providers by government controlled institutions, bureaucracy, lack of penalties for corruption of public officials, and lack of transparent laws and processes.[12][89] A Harvard University study finds these to be some of the causes of corruption and underground economy in India.[90]

Impact of corruption

Loss of credibility

In a study on bribery and corruption in India conducted in 2013[40] by global professional services firm Ernst & Young (EY), a majority of the survey respondents from PE firms said that a company operating in a sector which is perceived as highly corrupt may lose ground when it comes to fair valuation of its business, as investors bargain hard and factor in the cost of corruption at the time of transaction. Ever since Mr. Narendra Modi has taken up the office, it is believed that the levels of corruption has sharply decreased, however there are no studies available on this matter.

According to a report by KPMG, "high-level corruption and scams are now threatening to derail the country's its credibility and [its] economic boom".[91]

Economic loss

Corruption may lead to further bureaucratic delay and inefficiency if corrupted bureaucrats introduce red tape in order to extort more bribes.[92] Such inadequacies in institutional efficiency could affect growth indirectly by lowering the private marginal product of capital and investment rate.[93] Levine and Renelt showed that investment rate is a robust determinant of economic growth.[94]

Bureaucratic inefficiency also affects growth directly through misallocation of investments in the economy.[95] Additionally, corruption results in lower economic growth for a given level of income.[93]

Lower corruption, higher growth rates

If corruption levels in India were decreased to levels in developed economies such as Singapore or the United Kingdom, India's GDP growth rate could increase at a higher rate annually. C. K. Prahalad estimates the lost opportunity caused by corruption in terms of investment, growth and jobs for India is over US$50 billion a year.[1]

See also

- Economic history of India

- List of scandals in India

- Licence Raj

- Mafia Raj

- Uprising 2011, Indians Against Corruption

- Debt bondage in India

Anti-corruption:

- 2012 Indian anti-corruption movement

- 2011 Indian anti-corruption movement

- Jan Lokpal Bill

- Right to Public Services legislation

- Lok Ayukta

General:

- Corruption Perceptions Index

- Rent seeking

- Socio-economic issues in India

- International Anti-Corruption Academy

- Group of States Against Corruption

- International Anti-Corruption Day

- ISO 37001 Anti-bribery management systems

- United Nations Convention against Corruption

- OECD Anti-Bribery Convention

- Transparency International

References

- Nirvikar Singh (19 December 2010). "The trillion-dollar question". The Financial Express. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012.

- Transparency International – the global coalition against corruption, Transparency.org, archived from the original on 24 July 2011, retrieved 7 October 2011

- "India Corruption Study 2005: To Improve Governance: Volume I – Key Highlights New Delhi" (PDF). Transparency International India. 30 June 2005. pp. 1–3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 August 2013.

- "Corruption Perception Index 2019". Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- "India Corruption Study – 2008" (PDF). Transparency International. 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 6 July 2012.

- "India to give free medicine to millions". The Financial Times. 5 July 2012.

- "Indian rural welfare – Digging holes". The Economist. 5 November 2011. Archived from the original on 9 June 2012.

- "Cops turn robbers on India's roads". Asia Online. 27 August 2009.

- "White Paper on Black Money" (PDF). Ministry of Finance, Government of India. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 July 2012.

- "Banking secrecy spices up Indian elections". SWISSINFO – A member of Swiss Broadcasting Corporation. 14 May 2009. Archived from the original on 26 September 2013.

- "Survey on Bribery and Corruption – Impact on Economy and Business Environment" (PDF). KPMG. 2011. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 November 2012.

- Debroy and Bhandari (2011). "Corruption in India". The World Finance Review. Archived from the original on 9 February 2013.

- "A special report on India: The democracy tax is rising: Indian politics is becoming ever more labyrinthine". The Economist. 11 December 2008. Archived from the original on 20 December 2008.

- MDRA (February 2007). "Corruption in Trucking Operations in India" (PDF). The World Bank. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 April 2012.

- "How much do the corrupt earn?". The Economic Times. 11 September 2011. Archived from the original on 8 April 2016. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- "UP trucker won't give bribe, pays with his life". Indian Express. 27 September 2011.

- Indian bureaucracy ranked worst in Asia: Survey Archived 15 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine The Times of India, 3 June 2009.

- K.R. Gupta and J.R. Gupta, Indian Economy, Vol #2, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 2008, ISBN 81-269-0926-9. Snippet: ... the land market already stands subverted and an active land mafia has already been created ...

- "Mulayam Hits Mafia Hard". India Today. 16 October 2006. Archived from the original on 5 July 2011. Retrieved 30 October 2008. Snippet: ... The road sector has always been the main source of income for the mafia. They either ask their men directly to grab the contracts or allow an outsider to take the contract after accepting a hefty commission

- "India aid programme 'beset by corruption' – World Bank". BBC News. 18 May 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012.

- Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act Archived 21 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Govt of India

- Tom Wright and Harsh Gupta (29 April 2011). "India's Boom Bypasses Rural Poor". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 16 July 2017.

- "Health scam: Former CMO, Sachan booked". Hindustan Times. 4 August 2011. Archived from the original on 26 January 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "The New Indian Express". The New Indian Express. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- "NRHM scam: 6 officials booked in accountant's murder – India – DNA". Dnaindia.com. 17 February 2012. Archived from the original on 31 October 2012. Retrieved 13 August 2012.

- Reddy, Prashant (20 May 2012). "CSIR Tech. Pvt. Ltd: Its controversial past and its uncertain future". SpicyIP.com. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- "Indian Scientists Claim Lab Corruption". ScienceNOW. 23 January 1998. Archived from the original on 6 June 2013.

- Singh, Mahendra Pratap (13 February 2010). "GROUND REPORT INDIA: Without prejudice, fingers point to Rs. 50.00 Lakhs financial embezzlement by Dr. R. Tuli, Director". Archived from the original on 30 April 2013.

- Jayaraman, K.S. (9 November 2009). "Report row ousts top Indian scientist". Nature. 462 (7270): 152. doi:10.1038/462152a. PMID 19907467. Archived from the original on 18 December 2011. Retrieved 19 June 2012.

- Ayyadurai, VA Shiva; Sardana, Deepak (19 October 2009). "CSIR-TECH Path Forward" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 January 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2013.

- Ayyadurai, VA Shiva (16 December 2012). "VA Shiva's Lecture at Indian Science Congress Centenary". Archived from the original on 24 March 2013.

- Bhaduri, Sumit (8 January 2013). "Indian science must break free from the present bureaucratic culture to come up with big innovative ideas". Times of India.

- Jayaraman, K.S. (6 January 2012). "Indian science in need of overhaul". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2012.9750. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- "Corruption in Income-Tax: beaten by Babudom". LiveMint. Archived from the original on 25 June 2010.

- "Two Income Tax officials booked for corruption". The Indian Express. India. Archived from the original on 22 February 2016.

- "Dredging out mineral piracy, 7 September 2011". The Hindu, Business Line. Archived from the original on 10 October 2012.

- "Full Report of Karnataka Lokayukta on Illegal Mining of Iron Ore, 27 July 2011" (PDF). Chennai, India: The Hindu, Business Line. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2012.

- Bertrand, Marianne et al. Obtaining a Driver's License in India: An Experimental Approach to Studying Corruption, The Quarterly Journal of Economics (Nov 2007, No. 122,4)

- Corruption in Driver licensing Process in Delhi "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2012. Retrieved 2012-02-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Bribery and corruption: ground reality in India". Archived from the original on 23 August 2013.

- Roy and Narayan (2011). "India Corruption Study 2010" (PDF). CMS Transparency. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2011.

- David Loyn (1 March 2012). "British aid to India: Helping Bihar's poor". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 July 2012.

- Kar, Dev (2010). The Drivers and Dynamics of Illicit Financial Flows from India: 1948–2008 (PDF). Washington, DC: Global Financial Integrity. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2012.

- "Money in swiss banks: India slips to 75th position". The Dawn. 4 July 2016. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016.

- "India slips to 75th place on money in Swiss banks; UK on top". The Economic Times (India Times). 3 July 2016. Archived from the original on 9 July 2016.

- "The Hindu Business Line : Black, bold and bountiful". Thehindubusinessline.in. 13 August 2010. Archived from the original on 18 September 2011. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- There is no entity named Swiss Banking Association; there is, however, one named Swiss Bankers Association. For verifiability, this wikipedia article uses the misnomer interchangeably, since it was widely mentioned by Indian media.

- "Govt to reveal stand on black money on 25 Jan – India News – IBNLive". Ibnlive.in.com. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- "Govt To Reveal Stand on Black Money on 25 Jan | India news, Latest news India, Breaking news India, Current headlines India, News from India on Business, Sports, Politics, Bollywood and World News online". Currentnewsindia.com. 25 January 2011. Archived from the original on 24 March 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2011.

- "No 'black money' statistics exist: Swiss banks". The Times of India. 13 September 2009. Retrieved 13 November 2011.

- "No 'black money' statistics exist: Swiss banks". The Times of India. 13 September 2009.

- "How Indian companies are misusing public trusts to launder money". Archived from the original on 24 October 2015.

- "Gold price recovers on renewed demand". Hindustan Times. 10 November 2016. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Langa, Mahesh (9 November 2016). "Scramble for gold in Gujarat after demonetisation". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 11 November 2016. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "Defunct notes worth Rs. 44 lakh found in temple hundi". The Hindu. 14 November 2016. Archived from the original on 14 November 2016.

- Parmar, Beena (13 November 2016). "Despite Rs 4000-cap on money exchange, loophole allows multiple transactions". Hindustan Times. Archived from the original on 13 November 2016. Retrieved 13 November 2016.

- "Demonetisation: In Chennai, To beat cash limit, they send full teams to bank". The Indian Express. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 19 November 2016.

- "To reduce crowds at banks, ATMs, indelible ink to mark fingers of those who have exchanged old notes". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Demonetisation: Banks to use indelible ink to stop multiple transactions, curb crowd". firstpost. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016.

- "Demonetisation: Indelible ink mark seems like the government is panicking?". The Indian Express. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016.

- "Rlys sets 5000 as cash refund limit for tickets". Archived from the original on 13 January 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Railways say, no cash refund for tickets booked between Nov 9-11". Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 15 November 2016.

- "Demonetisation impact: Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation collects over Rs 160 crore in just four days". india.com. 15 November 2016. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- Pandey, Devesh K. (5 December 2016). "Two Axis Bank managers held in Delhi for laundering Rs. 40 cr". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 21 December 2016. Retrieved 8 May 2018 – via www.thehindu.com.

- "ED registers case against fake account holders in Axis Bank's Noida branch - Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". dnaindia.com. 17 December 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Axis Bank raided again, Rs 89 crore in 19 suspicious accounts found in Ahmedabad branch". financialexpress.com. 22 December 2016. Archived from the original on 16 September 2017. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- Praful Bidwai. "INDIA: Legal System in the Dock". Archived from the original on 7 March 2009.

- "Judiciary stares at morality crisis". India Today. 12 January 2014. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 17 April 2014.

- "Punjab clears Right to Services Act". 8 June 2011. Chennai, India: The Hindu. 8 June 2011. Archived from the original on 28 August 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "Corruption watchdog hails Bihar, MP govts as best service-providers". Times of India. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 4 December 2011.

- "PRS - All about the Lok Pal Bill". Archived from the original on 12 February 2012.

- "Lokpal Bill gets President's nod - The Times of India". The Times Of India. Archived from the original on 2 January 2014.

- "Notification" (PDF). Department of Personnel and Training, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2014. Retrieved 7 March 2014.

- "Indian Parliament passes Whistleblowers Protection Bill 2011". IANS. news.biharprabha.com. 21 February 2014. Archived from the original on 29 October 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- "Whistle Blowers Protection Act, 2011" (PDF). Gazette of India. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- "Companies Act 2013 What will be its impact on fraud in India?" (PDF). EY. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- Jen Swanson (15 August 2013). "India Seeks to Overhaul a Corporate World Rife With Fraud" ("Dealbook" blog). The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 November 2013. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- "Parliament passes Companies Bill 2012(Update)". Yahoo! News India. ANI. 8 August 2013. Archived from the original on 28 May 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2013.

- "A.P. Departments Anti-Corruption Bureau". A.P. Government. Archived from the original on 23 May 2010. Retrieved 25 June 2010.

- "Karnataka Lokayukta". National Informatics Centre. Archived from the original on 19 June 2010. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- PTI (19 June 2012). "Andhra cash-for-bail scam: Suspended judge questioned". The Times of India.

- Tariq Engineer (19 June 2012). "Srinivasan questioned in politician's corruption case". ESPN CricInfo. Archived from the original on 13 March 2014.

- https://www.thebetterindia.com/49752/zero-rupee-note-to-fight-corruption/

- G Babu Jayakumar (10 April 2011). "Wasn't easy for Anna's 'thambis'". The New Indian Express. India. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 12 May 2011.

- "Tata Tea and NGO launch programme on right to vote for youth". The Hindu. 16 September 2008. Archived from the original on 19 January 2009. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Articles". Tata Tea. Archived from the original on 11 June 2011. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- "Corruption in India – A rotten state". The Economist. 10 March 2011. Archived from the original on 18 August 2012.

- U Myint (December 2000). "CORRUPTION: CAUSES, CONSEQUENCES AND CURES" (PDF). Asia-Pacific Development Journal. 7 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 October 2011.

- Vito Tanzi (December 1998). Corruption Around the World – Causes, Consequences, Scope, and Cures. 45. IMF Staff Papers.

- Anant and Mitra (November 1998). "The Role of Law and Legal Institutions in Asian Economic Development: The Case of India" (PDF). Harvard University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 April 2016.

- Colvin, Geoff (20 April 2011). "Corruption: The biggest threat to developing economies". CNNMoney. Archived from the original on 30 April 2011. Retrieved 23 May 2011.

- Myrdal, Gunnar. Asian Drama: An Enquiry in the Poverty of Nations, The Australian Quarterly (Dec 1968, Vol. 40, 4)

- Mauro, Paolo. Corruption and Growth, The Quarterly Journal of Economics (Aug 1995, Vol. 110, 3)

- Levine, Ross. Renalt, David. A Sensitivity Analysis of Cross-Country Growth Regressions, Th American Economic Review (Sep 1992, Vol. 8, 4)

- "How Much do Distortions Affect Growth" (PDF). World Bank. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 June 2013.

Further reading

- Khatri, Naresh. 2013. Anatomy of Indian Brand of Crony Capitalism. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2335201

- Kohli, Suresh (1975). Corruption in India: The Growing Evil. India: Chetana Pvt.Ltd. ISBN 978-0-86186-580-2.

- Dwivedy, Surendranath; Bhargava, G. S. (1967). "Political Corruption in India". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gupta, K. N. (2001). Corruption in India. Anmol Publications Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-81-261-0973-9..

- Halayya, M. (1985). "Corruption in India". Affiliated East-West Press. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guhan, Sanjivi; Paul, Samuel (1997). "Corruption in India: Agenda for Action". Vision Books. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Vittal, N. (2003). Corruption in India: The Roadblock to National Prosperity. Academic Foundation. ISBN 978-81-7188-287-8.

- Somiah, C.G. (2010). The honest always stand alone. New Delhi: Niyogi Books. ISBN 978-81-89738-71-6.

- Kaur, Ravinder. "India Inc. and its Moral Discontents". Economic and Political Weekly.

- Sharma, Vivek Swaroop. "Give Corruption a Chance" in The National Interest 128, November/December 2013: 38–45. Full text available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/279587155_Give_Corruption_a_Chance.

- Arun Shourie (1992). These lethal, inexorable laws: Rajiv, his men and his regime. Delhi: South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0836427554

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Corruption in India |

- CIC – The Central Information Commission is charged with interpreting the Right to Information Act, 2005.

- DoPT – The Department of Personnel and Training, Ministry of Personnel, Public Grievances, and Pensions, is charged with being the nodal agency for the Right to Information Act, 2005. It has the powers to make rules regarding appeals, fees, etc.