Cumulonimbus cloud

Cumulonimbus (from Latin cumulus, "heaped" and nimbus, "rainstorm") is a dense, towering vertical cloud,[1] forming from water vapor carried by powerful upward air currents. If observed during a storm, these clouds may be referred to as thunderheads. Cumulonimbus can form alone, in clusters, or along cold front squall lines. These clouds are capable of producing lightning and other dangerous severe weather, such as tornadoes and hailstones. Cumulonimbus progress from overdeveloped cumulus congestus clouds and may further develop as part of a supercell. Cumulonimbus is abbreviated Cb.

| Cumulonimbus Cloud | |

|---|---|

Cumulonimbus | |

| Abbreviation | Cb. |

| Symbol | |

| Genus | Cumulonimbus (heaped, rain) |

| Species |

|

| Variety | None |

| Altitude | 500-16,000 m (2,000-52,000 ft) |

| Classification | Family C (Low-level) |

| Appearance | Very tall and large clouds |

| Precipitation cloud? | Very common, heavy at times |

| Part of a series on |

| Weather |

|---|

|

|

|

Appearance

Towering cumulonimbus clouds are typically accompanied by smaller cumulus clouds. The cumulonimbus base may extend several kilometres across and occupy low to middle altitudes - formed at altitude from approximately 200 to 4,000 m (700 to 10,000 ft). Peaks typically reach to as much as 12,000 m (39,000 ft), with extreme instances as high as 21,000 m (69,000 ft) or more.[2] Well-developed cumulonimbus clouds are characterized by a flat, anvil-like top (anvil dome), caused by wind shear or inversion near the tropopause. The shelf of the anvil may precede the main cloud's vertical component for many kilometres, and be accompanied by lightning. Occasionally, rising air parcels surpass the equilibrium level (due to momentum) and form an overshooting top culminating at the maximum parcel level. When vertically developed, this largest of all clouds usually extends through all three cloud regions. Even the smallest cumulonimbus cloud dwarfs its neighbors in comparison.

Species

- Cumulonimbus calvus: cloud with puffy top, similar to cumulus congestus which it develops from; under the correct conditions it can become a cumulonimbus capillatus.

- Cumulonimbus capillatus: cloud with cirrus-like, fibrous-edged top.[3]

Cumulonimbus calvus

Cumulonimbus calvus A clearly developed cumulonimbus fibrous-edged top capillatus

A clearly developed cumulonimbus fibrous-edged top capillatus

Accessory clouds

- Arcus (including roll and shelf clouds): low, horizontal cloud formation associated with the leading edge of thunderstorm outflow.[4]

- Pannus: accompanied by a lower layer of fractus species cloud forming in precipitation.[5]

- Pileus (species calvus only): small cap-like cloud over parent cumulonimbus.

- Velum: a thin horizontal sheet that forms around the middle of a cumulonimbus.[6]

Supplementary features

- Incus (species capillatus only): cumulonimbus with flat anvil-like cirriform top caused by wind shear where the rising air currents hit the inversion layer at the tropopause.[7]

- Mamma or mammatus: consisting of bubble-like protrusions on the underside.

- Tuba: column hanging from the cloud base which can develop into a funnel cloud or tornado. They are known to drop very low, sometimes just 6 metres (20 ft) above ground level.[6]

- Flanking line is a line of small cumulonimbus or cumulus generally associated with severe thunderstorms.

- An overshooting top is a dome that rises above the thunderstorm; it is associated with severe weather.

Precipitation-based supplementary features

- Rain: precipitation that reaches the ground as liquid, often in a precipitation shaft.[8]

- Virga: precipitation that evaporates before reaching the ground.[6]

Arcus cloud (shelf cloud) leading a thunderstorm

Arcus cloud (shelf cloud) leading a thunderstorm A cap (pileus) atop a congestus

A cap (pileus) atop a congestus Incus with a velum edge

Incus with a velum edge Mammatocumulus with drooping pouches

Mammatocumulus with drooping pouches A funnel cloud (tuba) over the Netherlands

A funnel cloud (tuba) over the Netherlands Flanking line in front of a strong thunderstorm

Flanking line in front of a strong thunderstorm An overshooting top is a dome of clouds atop a cumulonimbus

An overshooting top is a dome of clouds atop a cumulonimbus Cumulonimbus calvus against sunlight with rain falling beneath it as a rain shaft (praecipatio)

Cumulonimbus calvus against sunlight with rain falling beneath it as a rain shaft (praecipatio) Rain evaporating before reaching the ground (virga)

Rain evaporating before reaching the ground (virga)

Effects

Cumulonimbus storm cells can produce torrential rain of a convective nature (often in the form of a rain shaft) and flash flooding, as well as straight-line winds. Most storm cells die after about 20 minutes, when the precipitation causes more downdraft than updraft, causing the energy to dissipate. If there is enough solar energy in the atmosphere, however (on a hot summer day, for example), the moisture from one storm cell can evaporate rapidly—resulting in a new cell forming just a few kilometres from the former one. This can cause thunderstorms to last for several hours. Cumulonimbus clouds can also bring dangerous winter storms (called "blizzards") which bring lightning, thunder, and torrential snow. However, cumulonimbus clouds are most common in tropical regions.[9]

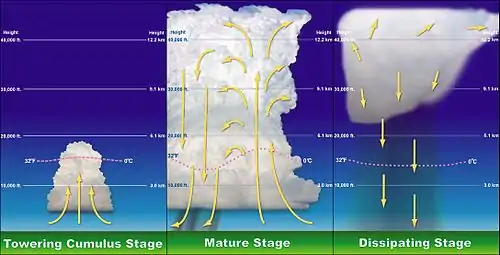

Life cycle or stages

In general, cumulonimbus require moisture, an unstable air mass, and a lifting force (heat) in order to form. Cumulonimbus typically go through three stages: the developing stage, the mature stage (where the main cloud may reach supercell status in favorable conditions), and the dissipation stage.[10] The average thunderstorm has a 24 km (15 mi) diameter and a height of approximately 12.2 km (40,000 ft). Depending on the conditions present in the atmosphere, these three stages take an average of 30 minutes to go through.[11]

Cloud types

Clouds form when the dewpoint temperature of water is reached in the presence of condensation nuclei in the troposphere. The atmosphere is a dynamic system, and the local conditions of turbulence, uplift and other parameters give rise to many types of clouds. Various types of cloud occur frequently enough to have been categorized. Furthermore, some atmospheric processes can make the clouds organize in distinct patterns such as wave clouds or actinoform clouds. These are large-scale structures and are not always readily identifiable from a single point of view.

See also

References

- World Meteorological Organization, ed. (1975). Cumulonimbus, International Cloud Atlas. I. pp. 48–50. ISBN 92-63-10407-7. Retrieved 28 November 2014.

- Haby, Jeff. "Factors Influencing Thunderstorm Height". theweatherprediction.com. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- World Meteorological Organization, ed. (1975). Species, International Cloud Atlas. I. pp. 17–20. ISBN 92-63-10407-7. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- Ludlum, David McWilliams (2000). National Audubon Society Field Guide to Weather. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 473. ISBN 0-679-40851-7. OCLC 56559729.

- Allaby, Michael, ed. (2010). "Pannus". A Dictionary of Ecology (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199567669.

- World Meteorological Organization, ed. (1975). Features, International Cloud Atlas. I. pp. 22–24. ISBN 92-63-10407-7. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "Cumulonimbus Incus". Universities Space Research Association. 5 August 2009. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- Dunlop, Storm (2003). The Weather Identification Handbook. The Lyons Press. pp. 77–78. ISBN 1585748579.

- "Flying through 'Thunderstorm Alley'". New Straits Times. 31 December 2014. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018.

- Michael H. Mogil (2007). Extreme Weather. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publisher. pp. 210–211. ISBN 978-1-57912-743-5.

- National Severe Storms Laboratory (15 October 2006). "A Severe Weather Primer: Questions and Answers about Thunderstorms". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on 25 August 2009. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cumulonimbus clouds. |