Cyathus striatus

Cyathus striatus, commonly known as the fluted bird's nest,[5] is a common saprobic bird's nest fungus with a widespread distribution throughout temperate regions of the world. This fungus resembles a miniature bird's nest with numerous tiny "eggs"; the eggs, or peridioles, are actually lens-shaped bodies that contain spores. C. striatus can be distinguished from most other bird's nest fungi by its hairy exterior and grooved (striated) inner walls. Although most frequently found growing on dead wood in open forests, it also grows on wood chip mulch in urban areas. The fruiting bodies are encountered from summer until early winter. The color and size of this species can vary somewhat, but they are typically less than a centimeter wide and tall, and grey or brown in color. Another common name given to C. striatus, splash cups, alludes to the method of spore dispersal: the sides of the cup are angled such that falling drops of water can dislodge the peridioles and eject them from the cup.[6][7] The specific epithet is derived from the Latin stria, meaning "with fine ridges or grooves".[8]

| Cyathus striatus | |

|---|---|

_Willd_274333.jpg.webp) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Division: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | C. striatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Cyathus striatus | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

| Cyathus striatus | |

|---|---|

float | |

| glebal hymenium | |

| cap is infundibuliform | |

| hymenium attachment is not applicable | |

| lacks a stipe | |

| ecology is saprotrophic | |

| edibility: inedible | |

Taxonomy

Cyathus striatus was first described by William Hudson in his 1778 work Flora Anglica as Peziza striata.[9] Carl Ludwig Willdenow transferred it to Cyathus in 1787.[10]

Description

The "nest", or peridium, is usually about 7 to 10 mm in height and 6 to 8 mm in width,[7] but the size is somewhat variable and specimens have been found with heights and widths of up to 1.5 cm (0.59 in).[6] The shape typically resembles a vase or inverted cone. The outer surface (exoperidium) ranges in color from slightly brownish to grayish buff to deep brown; the exoperidium has a shaggy or hairy texture (a tomentum), with the hairs mostly pointing downward. The inner surface of the peridium (the endoperidium) is striated or grooved, and shiny. Young specimens have a lid, technically called an epiphragm, a thin membrane that covers the cup opening. The epiphragm is hairy like the rest of the exoperidial surface, but the hairs often wear off leaving behind a thin white layer stretched across the lid of the cup. As the peridium matures and expands, this membrane breaks and falls off, exposing the peridioles within.[12] The peridium is attached to its growing surface by a mass of closely packed hyphae called an emplacement; in C. striatus the maximum diameter of the emplacement is typically 8–12 mm, and often incorporating small fragments of the growing surface into its structure.[13] The species is inedible.[14]

Peridiole structure

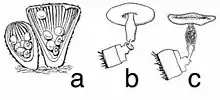

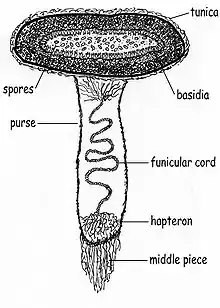

The peridioles are about 1 to 1.5 mm wide and rarely up to 2 mm wide. They are disc-shaped, but may appear angular due to pressure from neighbouring peridioles. Peridioles may be dark, or a drab gray if still covered with a thin membrane called a tunica.[15]

Peridioles in C. striatus are sheathed and attached to the endoperidium by complex cords of mycelia known as a funiculus in the singular. The funiculus is differentiated into three regions: the basal piece, which attaches it to the inner wall of the peridium, the middle piece, and an upper sheath, called the purse, connected to the lower surface of the peridiole. Inside the purse and middle piece is a coiled thread of interwoven hyphae called the funicular cord, attached at one end to the peridiole and at the other end to an entangled mass of hyphae called the hapteron. When dry the funiculus is brittle, but when wet it is capable of long extension.[12]

Microscopic characteristics

The basidia, the spore-bearing cells, are club-shaped with long stalks. They typically hold 4 spores that are sessile, that is, attached directly to the surface of the basidium, rather than by a short stalk (a sterigmata).[16] Spores measure about 15 to 20 μm long by 8 to 12 μm wide. They are elliptical, smooth, hyaline, and notched at one end.[6][7] During development, the spores are separated from the basidia when the latter collapse and gelatinize along with other cells lining the inner walls of the peridiole. The spores expand in size somewhat after being detached from the basidia.[16]

Habitat and distribution

Cyathus striatus is a saprobic fungus, deriving its nutrition from decaying organic material, and is typically found growing in clusters on small twigs or other woody debris. It is also common on mulch under shrubs.[17] The features of the microenvironment largely influence the appearance of C. striatus; all else being equal, it is more likely to be found in moist, shallow depressions than elevated areas.[18] It is very widespread in temperate areas throughout the world,[15] growing in summer and fall.[19] The fungus has been recorded from Asia, Europe, North America, Central America, South America, and New Zealand.[20]

Life cycle

Cyathus striatus can reproduce both asexually (via vegetative spores), or sexually (with meiosis), typical of taxa in the basidiomycetes that contain both haploid and diploid stages. Basidiospores produced in the peridioles each contain a single haploid nucleus. After the spores have been dispersed into a suitable growing environment, they germinate and develop into homokaryotic hyphae, with a single nucleus in each cell compartment. When two homokaryotic hyphae of different mating compatibility groups fuse with one another, they form a dikaryotic mycelia in a process called plasmogamy. After a period of time and under the appropriate environmental conditions, fruiting bodies may be formed from the dikaryotic mycelia. These fruiting bodies produce peridioles containing the basidia upon which new spores are made. Young basidia contain a pair of haploid sexually compatible nuclei which fuse, and the resulting diploid fusion nucleus undergoes meiosis to produce haploid basidiospores.[21] The process of meiosis in C. striatus has been found to be similar to that of higher organisms.[22]

Spore dispersal

The cone shaped fruiting body of Cyathus striatus makes use of a splash-cup mechanism to help disperse the spores. When a raindrop hits the interior of the cup with the optimal angle and velocity, the downward force of the water ejects the peridioles into the air. The force of ejection rips open the funiculus, releasing the tightly wound funicular cord. The hapteron attached to the end of the funiculus is adhesive, and when it contacts a nearby plant stem or stick, the hapteron sticks to it; the funicular cord wraps around the stem or stick powered by the force of the still-moving peridiole (similar to a tetherball). The peridioles degrade over time to eventually release the spores within, or they may be eaten by herbivorous animals and redeposited after passing through the digestive tract.[23]

Bioactive compounds

Cyathus striatus has proven to be a rich source of bioactive chemical compounds. It was first reported in 1971 to produce "indolic" substances (compounds with an indole ring structure) as well as a complex of diterpenoid antibiotic compounds collectively known as cyathins.[24][25] Several years later, research revealed the indolic substances to be compounds now known as striatins. Striatins (A, B and C) have antibiotic activity against fungi imperfecti, and various Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria.[26] C. striatus also produces sesquiterpene compounds called schizandronols.[27] It also contains the triterpene compounds glochidone, glochidonol, glochidiol and glochidiol diacetate, cyathic acid, striatic acid, cyathadonic acid and epistriatic acid.[28] The latter four compounds were unknown prior to their isolation from C. striatus.

See also

References

- "GSD Species Synonymy: Cyathus striatus". Index Fungorum. CAB International. Retrieved 2014-07-01.

- Bulliard P. (1791). Histoire des champignons de la France. I (in French). Paris, France. p. 166 (figure 40A).

- de Brotero F. (1804). Flora Lusitanica. 2. Lisbon, Portugal. p. 474.

- Berkeley MJ (1839). "Descriptions of exotic fungi in the collection of Sir W.J. Hooker, from memoirs and notes of J.F. Klotzsch, with additions and corrections". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. I. 3: 375–401. doi:10.1080/03745483909443251.

- Phillips R. "Cyathus striatus". Roger's Plants. Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Lincoff GH (1981). National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Mushrooms. New York: Random House. pp. 828–9. ISBN 978-0-394-51992-0.

- Kuo M. (February 2014). "Cyathus striatus". MushroomExpert.Com.

- Brodie, The Bird's Nest Fungi, p. 173.

- Hudson W. (1778). Flora anglica (2nd ed.). London, UK: Impensis auctoris: Prostant Venales apud J. Nourse. p. 634.

- von Willdenow CL. (1787). Florae Berolinensis Prodromus. Berlin, Germany: Wilhelm Vieweg. p. 399.

- Gymme-Vaughan HCI, Barnes B (1927). The Structure and Development of the Fungi. Cambridge at the University Press. p. 315, figure 281.

- Gates CL (1906). "The Nidulariaceae". Mycological Writings. 2: 1–30.

- Brodie, The Bird's Nest Fungi, p. 68.

- Phillips, Roger (2010). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of North America. Buffalo, NY: Firefly Books. p. 341. ISBN 978-1-55407-651-2.

- Brodie, The Bird's Nest Fungi, p. 175.

- Martin GW (1927). "Basidia and spores of the Nidulariaceae". Mycologia. 19 (5): 239–47. doi:10.2307/3753710. JSTOR 3753710.

- Healy RA, Huffman DR, Tiffany LH, Knaphaus G (2008). Mushrooms and Other Fungi of the Midcontinental United States (Bur Oak Guide). Iowa City: University of Iowa Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-58729-627-7.

- Brodie, The Bird's Nest Fungi, p. 101.

- Emberger G. "Cyathus striatus". Messiah College. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- Roberts P, Evans S (2011). The Book of Fungi. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. p. 533. ISBN 978-0-226-72117-0.

- Deacon J. (2005). Fungal Biology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishers. pp. 31–2. ISBN 978-1-4051-3066-0.

- Lu B, Brodie HJ (1964). "Preliminary observations of meiosis in the fungus Cyathus". Canadian Journal of Botany. 42 (3): 307–10. doi:10.1139/b64-026.

- Brodie, The Bird's Nest Fungi, pp. 80–92.

- Johri BN, Brodie HJ (1971). "Extracellular production of indolics by the fungus Cyathus". Mycologia. 63 (4): 736–44. doi:10.2307/3758043. JSTOR 3758043. PMID 5111071.

- Allbutt AD, Ayer WA, Brodie HJ, Johri BN, Taube H (1971). "Cyathin, a new antibiotic complex produced by Cyathus helenae". Canadian Journal of Microbiology. 17 (11): 1401–7. doi:10.1139/m71-223. PMID 5156938.

- Anke T, Oberwinkler F (1977). "The striatins—new antibiotics from the basidiomycete Cyathus striatus (Huds. ex Pers.) Willd". The Journal of Antibiotics. 30 (3): 221–5. doi:10.7164/antibiotics.30.221. PMID 863783.

- Ayer WA, Reffstrup T (1982). "Metabolites of bird's nest fungi. Part 18. New oxygenated cadinane derivatives from Cyathus striatus". Tetrahedron. 38 (10): 1409–12. doi:10.1016/0040-4020(82)80221-4.

- Ayer AW, Flanagan RJ, Reffstrup T (1984). "Metabolites of bird's nest fungi-19 New triterpenoid carboxylic acids from Cyathus striatus and Cyathus pygmaeus". Tetrahedron. 40 (11): 2069–82. doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(01)88448-9.

Cited text

Brodie HJ (1975). The Bird's Nest Fungi. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-5307-7.

External links

- Tom Volk's Fungi Description and ecology

![]() Media related to Cyathus striatus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Cyathus striatus at Wikimedia Commons