Dark Star (film)

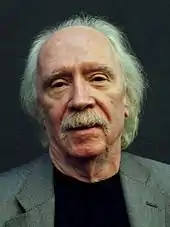

Dark Star is a 1974 American science fiction comedy film directed and produced by John Carpenter and co-written with Dan O'Bannon. It follows the crew of the deteriorating starship Dark Star, twenty years into their mission to destroy unstable planets that might threaten future colonization of other planets.

| Dark Star | |

|---|---|

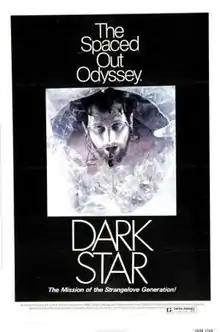

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | John Carpenter |

| Produced by | John Carpenter |

| Written by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Music by | John Carpenter |

| Cinematography | Douglas Knapp |

| Edited by | Dan O'Bannon |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Bryanston Distributing Company |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes[1] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $60,000[2] |

Beginning as a University of Southern California student film produced from 1970 to 1972, the film was gradually expanded to feature film length by 1974, when it appeared at Filmex before receiving a limited theatrical release in 1975. Its final budget is estimated at $60,000.[3] While initially unsuccessful with audiences, it was relatively well received by critics and continued to be shown in theaters as late as 1980.[4] The home video revolution of the early 1980s helped the film achieve "cult classic" status, and O'Bannon collaborated with home video distributor VCI in the production of versions on VHS, LaserDisc, and DVD.

The feature directorial debut for Carpenter, and the feature debut for O'Bannon, Dark Star was also produced and scored by Carpenter, while O'Bannon also served as editor, production designer, and visual effects supervisor and appeared as Sergeant Pinback.[5]

Plot

In the mid-22nd century, mankind has begun colonizing the far reaches of the universe. Armed with artificially intelligent "Thermostellar Triggering Devices," the scout ship Dark Star and its crew have been alone in space for 20 years on a mission to destroy "unstable planets" which might threaten future colonization of other planets.

The ship is in a state of deterioration and there are frequent system malfunctions (for example, an irreparable radiation leak, their cargo of intelligent talking bombs lowering from their bomb bay without a command to do so, and an explosion destroying their sleeping quarters), and only the voice of the ship's computer for company. The Dark Star′s commanding officer, Commander Powell, was killed during hyperdrive as a result of an electrical short-circuit behind his rear seat panel, but remains aboard the ship in a state of cryogenic suspension. The ship's remaining crew consists of its new commanding officer, Lieutenant Doolittle (helmsman, and originally second-in-command), Sergeant Pinback (bombardier), Corporal Boiler (navigator), and Talby (target specialist). As the tedium of their tasks over 20 years has driven them "around the bend", they have created distractions for themselves: Doolittle, formerly a surfer from Malibu, California, has constructed a musical bottle organ; Talby spends his time in the ship's observation dome, content to watch the universe go by; Boiler obsessively trims his mustache, smokes cigars, and shoots targets with the ship's emergency laser rifle in a corridor.

Pinback plays practical jokes on the crew members, maintains a video diary, and has adopted a ship's mascot in the form of a mischievous "beach ball"-like alien who refuses to stay in a storage room, forcing Pinback to chase it around the ship and eventually kill it with a gun. Pinback claims he is actually liquid fuel specialist Bill Frug, who inadvertently took the "real" Sergeant Pinback's place after he committed suicide by jumping into a fuel tank.

En route to their next target (the Veil Nebula[6]), the Dark Star is hit by a bolt of electromagnetic energy during a storm, resulting in yet another on-board malfunction, with "Thermostellar Bomb #20" receiving an order to deploy. The ship's computer convinces Bomb #20 that the order was in error, and persuades the bomb to disarm itself and return to the bomb bay. Talby notes the malfunction, and investigates the fault. He discovers a damaged communications laser in the emergency airlock while the crew is engaging in their next bombing run. While Talby attempts to repair it, the laser malfunctions, blinding Talby and knocking him unconscious, causing extensive damage to the main computer, and damaging the bomb release mechanism on Bomb #20.

Due to the damage to the ship's computer, the crew members cannot activate the release mechanism and attempt to abort the drop. After two prior accidental deployments, Bomb #20 refuses to disarm or abort the countdown sequence. The computer activates dampers to confine the blast to a diameter of one mile, but that is all it can do at the moment. As Pinback and Boiler try to talk the bomb out of blowing up underneath the ship, Doolittle revives Commander Powell, who advises him to teach the bomb the rudiments of phenomenology. After donning a space suit and exiting the ship to approach the bomb directly, Doolittle engages in a philosophical conversation with Bomb #20 until it decides to abort its countdown and retreat to the bomb bay for further contemplation.

When attempting to assist Doolittle in re-entering the ship, Pinback inadvertently jettisons Talby out of the airlock. As Doolittle tries to rescue the now-conscious Talby, Pinback addresses the bomb over the intercom in another attempt to disarm it. Doolittle has mistakenly taught the bomb Cartesian doubt and, as a result, Bomb #20 determines that it can only trust itself and not external input. Convinced that only it exists, and that its sole purpose in life is to explode, Bomb #20 detonates. The Dark Star is destroyed, and Pinback and Boiler are killed instantly. Commander Powell is flung into space encased in ice, and Talby and Doolittle are blown in opposite trajectories. Talby drifts into the Phoenix Asteroids (a cluster he has long had a fascination with), destined to circumnavigate the universe for eternity. As Doolittle loses contact with Talby, he sees that he is falling toward the unstable planet. As the film comes to an end, realizing he will burn up upon entering its atmosphere, he drifts into debris from the Dark Star, finds a surfboard-shaped hunk of debris, and "surfs" down into the atmosphere, dying as a falling star.

Cast

- Brian Narelle as Lieutenant Doolittle

- Dan O'Bannon as Sergeant Pinback

- Cal Kuniholm as Boiler

- Andreijah "Dre" Pahich as Talby

- John Carpenter as Talby (voice)[7]

- Joe Saunders as Commander Powell

- John Carpenter as Commander Powell (voice)[8]

- Barbara "Cookie" Knapp as Computer[9]

- Dan O'Bannon as Bomb #19 (credited as "Alan Sheretz")

- Dan O'Bannon as Bomb #20 (credited as "Adam Beckenbaugh")

- Miles Watkins as Mission Control

- Nick Castle as Alien[10]

Production

Screenplay

The screenplay was written by John Carpenter and Dan O'Bannon while film students at the University of Southern California.[7] Initially titled The Electric Dutchman, the original concept was Carpenter's, with O'Bannon "fleshing out many of the original ideas" and contributing many of the funniest moments.[11] According to O'Bannon, "The ending was copped from Ray Bradbury's story Kaleidoscope", found in the short story collection The Illustrated Man (1951).[12] O'Bannon references one of his USC teachers, William Froug, when Pinback says in a video diary entry "I should tell you my name is not really Sergeant Pinback, my name is Bill Frug."[13]

Filming

The film began as a 45-minute 16mm student project with a final budget of six thousand dollars.[14][15] Beginning with an initial budget of one thousand dollars from USC in 1970,[16] Carpenter and O'Bannon completed the first version of the film in 1972.[7] Carpenter had to replace the voice of Pahich with his own as Talby.[15] To achieve theatrical length, an additional fifty minutes were filmed with the support of Canadian distributor Jack Murphy (credited as "Production Associate").[7][17] Through John Landis, a friend of O'Bannon, the film came to the attention of producer-distributor Jack H. Harris, who obtained the theatrical distribution rights to the film, and insisted on extensive cuts to the existing film as well as the shooting of additional 35mm footage to bring the movie back up to feature film length[18][10] O'Bannon would later lament that as a result of the padding into a feature-length movie, "We had what would have been the world’s most impressive student film and it became the world’s least impressive professional film".[19]

Special effects

Many special effects were done by Dan O'Bannon, ship design was by Ron Cobb, model work by O'Bannon and Greg Jein, and animation was done by Bob Greenberg.[7] Cobb drew the original design for the Dark Star ship on a napkin while eating at the International House of Pancakes.[20]

To depict the transit of the Dark Star ship into hyperspace, O'Bannon devised an animated effect in which stars in space turn into streaks of light while the spaceship appears to be motionless. He created this effect by tracking the camera while leaving the shutter open. This is considered to be the first depiction in cinema history of a ship jumping into hyperspace. It is thought that O'Bannon was influenced by the striking "star gate" sequence created by Douglas Trumbull for the 1968 film 2001: A Space Odyssey. The streaking hyperspace effect was later employed in Star Wars (1977).[21][22]

Release

The completed film premiered on March 30, 1974 at Filmex, the Los Angeles International Film Exposition, for which Carpenter described the film as "Waiting for Godot in outer space."[23][24] Harris sold the film to Bryanston Pictures,[18] who released it to fifty theatres on January 16, 1975.[25][26] Following the success of Alien and Halloween, Dark Star was re-released June 1979 by the Atlantic Releasing Corporation as "...from the author of 'Alien' & the director of 'Halloween'..." with the tag line, "The Ultimate Cosmic Comedy!"[27]

Home media

VCI Entertainment released a theatrical cut of Dark Star on videocassette in August 1983.[28] After criticism of the release by O'Bannon in 1983, a new widescreen video master copy was created based on his personal 35mm print,[29] and a widescreen "Special Edition" was released by 1986.[30]

Director's cut

O'Bannon re-edited the film into a seventy-two minute "director's cut" released on LaserDisc in 1992, removing much of the footage shot for the theatrical release.[31]

Special edition

The film was released on DVD March 23, 1999 and included both a sixty-eight minute "special edition" and the longer original theatrical release.[32] A two-disc "Hyperdrive Edition" DVD was released on October 26, 2010, which again included both versions of the film, as well as the feature-length documentary Let There be Light: The Odyssey of Dark Star, exploring the origins of Dark Star and how it was produced.[33][34] In 2012, a "Thermostellar Edition" Blu-ray was released, including only the theatrical version, along with the special features of the 2010 DVD release.[35]

Reception

While greeted enthusiastically by the crowd at Filmex, the film was not well received upon its initial theatrical release. Carpenter and O'Bannon reported seeing nearly empty theatres and a lack of reaction to the film's humor.[36] The home video cassette revolution of the early 1980s saw Dark Star become a cult film among sci-fi fans.[37][25]

Critical response

An early review from Variety, recalled by Carpenter as "the first bad review I got", described the film as "a limp parody of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey that warrants attention only for some remarkably believable special effects achieved with very little money."[38][3] After its re-release in 1979, Roger Ebert gave the film three stars out of four, writing: "Dark Star is one of the damnedest science fiction movies I've ever seen, a berserk combination of space opera, intelligent bombs, and beach balls from other worlds."[4] Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a 77% fresh rating from 26 reviews, with the following consensus: "A loopy 2001 satire, Dark Star may not be the most consistent sci-fi comedy, but its portrayal of human eccentricity is a welcome addition to the genre."[39] Leonard Maltin awarded the film two and a half stars, describing it as "enjoyable for sci-fi fans and surfers", and complimenting the effective use of the limited budget.[40]

Influence

The "Beachball with Claws" segment of the film was reworked by Dan O'Bannon into the science fiction-horror film Alien (1979).[5][41] After witnessing audiences failing to laugh at parts of Dark Star which were intended as humorous, O'Bannon commented, "If I can't make them laugh, then maybe I can make them scream."[42]

Doug Naylor has said in interviews that Dark Star was the inspiration for Dave Hollins: Space Cadet, the radio sketches that evolved into the television science fiction situation comedy Red Dwarf.[43] The character Pinback also inspired the character name Pinbacker, the antagonist in Danny Boyle's film Sunshine (2007).[44][45] Dark Star has also been cited as a large inspiration for Machinima series Red vs. Blue by the series' creator, Burnie Burns.[46]

Metal Gear series creator Hideo Kojima revealed the iDroid's voice was inspired by the female computer voice from Dark Star.[47]

The indie rock band Pinback adopted its name from the character Sergeant Pinback, and frequently used samples from the movie in its early work.[48] British synth-pop band Erasure sampled dialogue from this film (along with Barbarella) in their song, "Sweet, Sweet Baby", the B-side to "Drama!", the debut single off their album, Wild! (1989). The Human League also used a sample from the film at the end of "Circus of Death", the b-side of their debut single, "Being Boiled". Cem Oral, under the alias of Oral Experience, also sampled dialogue from this film in his song "Never Been on E". The Polish band Spaceslug used a sample of the dialogue with Bomb #20 on the track Beneath the Haze from their 2019 release Reign of the Orion.

Soundtrack

The music for Dark Star is chiefly a pure electronic score created by Carpenter using a modular synthesizer.[49]

The song played during the opening and closing credits is "Benson, Arizona."[50] The music was written by John Carpenter, while the lyrics were written by Bill Taylor, concerning a man who travels the galaxy at light speed and misses his beloved back on Earth.[26] The lead vocalist was John Yager, a college friend of Carpenter's who was not a professional musician, "apart from being in a band in college."[51] Not coincidentally, there is actually a Dark Star Road in Benson, Arizona.

See also

References

- "Dark Star (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. January 3, 1978. Retrieved October 29, 2012.

- Smith, Adam (January 1, 2000). "Dark Star Review". Empire. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- Variety Staff (1974). "Review: 'Dark Star'". Variety. Variety Media. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

Pic began in 1970 as 45-minute USC Film School short. Final budget was $60,000.

- Ebert, Roger (March 11, 1980). "Dark Star (***)". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- Maçek III, J.C. (November 21, 2012). "Building the Perfect Star Beast: The Antecedents of 'Alien'". PopMatters.

- Carpenter, John; O'Bannon, Dan. ""Dark Star", short film script". Retrieved June 5, 2013.

- Cumbow, Robert (July 16, 2002). Order in the Universe: The Films of John Carpenter. Scarecrow Press. pp. 11–14, 244–245. ISBN 978-0-585-38302-6.

- "Dark Star Soundtrack". The Official John Carpenter. John Carpenter. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016.

Commander Powell, Talby – John Carpenter

- Hefley, Robert M. (June 1977). Zimmerman, Howard (ed.). "The Starlog Science Fiction Address Guide — Motion Pictures". Starlog. Vol. 1 no. 6. New York: O'Quinn Studios. p. 37 – via Internet Archive.

- Zinoman, Jason (July 7, 2011). Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror. Penguin. pp. 56–59. ISBN 978-1-101-51696-6.

- Kane, Paul; O’Regan, Marie (October 28, 2010). Voices in the Dark: Interviews with Horror Writers, Directors and Actors. McFarland. pp. 117–. ISBN 978-0-7864-5672-7.

- Fleming, John (December 1978). Skinn, Dez (ed.). "Dark Star Review". Starburst. Vol. 1 no. 5. London: Marvel UK. pp. 22–27 – via Internet Archive.

- Froug, William (2005). How I Escaped from Gilligan's Island: And Other Misadventures of a Hollywood Writer-Producer. Popular Press. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-0-87972-873-1.

- Rausch, Andrew J. (February 7, 2008). Fifty Filmmakers: Conversations with Directors from Roger Avary to Steven Zaillian. McFarland. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-7864-8409-6.

- Fischer, Dennis (January 1, 1991). Horror Film Directors, 1931-1990. McFarland. p. 118. ISBN 978-0-89950-609-8.

The original short was 45 minutes long and cost a mere $6,000 to produce using the equipment at USC.

- Stevenson, James (January 28, 1980). "People Start Running". The New Yorker. Condé Nast. Retrieved June 20, 2017.

- Fox, Jordan R. (1980). Kaplan, Michael (ed.). "Carpenter: Riding High on Horror". Cinefantastique. Vol. 10 no. 1. Oak Park, Illinois: Frederick S. Clarke. pp. 5–10.

I financed it until the summer of 1972, when a man named Jack Murphy, who owned a small Canadian distribution company, came on the picture.

- Weaver, Tom (January 1, 2006). Interviews with B Science Fiction and Horror Movie Makers: Writers, Producers, Directors, Actors, Moguls and Makeup. McFarland. pp. 205–. ISBN 978-0-7864-2858-8.

- Phipps, Keith (September 3, 2014). "Future Suck". The Dissolve. Pitchfork Media. Retrieved June 21, 2017.

- Cobb, Ron (2015). "Dark Star". RonCobb.net. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

Sketched on a napkin over coffee with Dan O'Bannon at the House of Pancakes L.A.

- Taylor, Chris (2014). How Star Wars Conquered the Universe: The Past, Present, and Future of a Multibillion Dollar Franchise. Head of Zeus. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-78497-045-1. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- "Dark Star". Kitbashed. Retrieved January 5, 2021.

- Staff (April 19, 1974). "The '74 Filmex Breaks All Records". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. Retrieved June 24, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- Boulenger, Gilles (2003). John Carpenter: The Prince of Darkness. Silman-James Press. ISBN 978-1-879505-67-4.

And 'Waiting for Godot in outer space' was the best made-up I could come up with.

- Konow, David (October 2, 2012). Reel Terror: The Scary, Bloody, Gory, Hundred-Year History of Classic Horror Films. St. Martin's Press. p. 248. ISBN 978-1-250-01359-0.

- Muir, John Kenneth (2005). The Films of John Carpenter. McFarland. pp. 53–63. ISBN 978-0786422692.

- Shannon, Eddie (August 4, 2014). "Dark Star /special /1979 re-release /USA". Film on Paper. Retrieved June 23, 2017.

- Bowden, Robert (August 13, 1983). "Vintage musical, space spoof and rockabilly exercises on new videocassettes". Tampa Bay Times. St. Petersburg, Florida – via Newspapers.com.

- Blair, Robert A. (October 1, 2010). "When you wish upon a DARK STAR..." VCI Classic Films.

- Lovece, Frank (August 24, 1986). "Compleat Carpenter available on video". The News Leader. Staunton, Virginia – via Newspapers.com.

- Mad Man From Mars (1992). "Dark Star". Pond Scum (Newsletter). Vol. 1 no. 29 – via LaserRot.

- Hunt, Bill (May 4, 1999). "Dark Star". The Digital Bits. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Abrams, Simon (November 3, 2010). "Dark Star". Slant Magazine. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Reis, George R., ed. (2010). "Dark Star Promo". DVD-Drive-In. Retrieved June 26, 2017.

- McKelvey, John (January 1, 2017). "Controversial Blus: Dark Star (DVD/ Blu-ray Comparison)". DVD Exotica. Tomorrow Wendy Productions. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

- Sherman, Craig (June 1, 2001). "Comedic Crewman". ArtsEditor.

- DiMare, Philip C. (June 17, 2011). Movies in American History: An Encyclopedia. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 595. ISBN 978-1-59884-297-5.

- Beahm, Justin (June 23, 2016). "On John Carpenter + Career Retrospective Interview". Justin Beahm. Retrieved June 27, 2017.

That was the first bad review I got, in the Daily Variety

- "Rotten Tomatoes – Dark Star". Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- Maltin, Leonard (2009), p. 320. Leonard Maltin's Movie Guide. ISBN 1-101-10660-3. Signet Books. Accessed May 8, 2012

- Konow, David (September 2004). "Alien, 25 Years Later: Dan O'Bannon Looks Back on His Scariest Creation". Creative Screenwriting. Vol. 11 no. 5. pp. 70–73.

'Beach Ball Alien' scenes in 'Dark Star' were an inspiration for 'Alien'.

- Puccio, John. J. DARK STAR - DVD review, Movie Metropolis

- Gilliam, JD (October 1, 2012). "Interview: RED DWARF Writer / Co-Creator DOUG NAYLOR". Starburst. Retrieved June 19, 2017.

I remember remarking to Rob at the time that I couldn’t believe no-one had done a sitcom like that because it seemed like such a good thing to do. So it was the old memory of Dark Star and the Dave Hollins sketch and we decided to try and write it.

- Kermode, Mark (March 25, 2007). "2007: a scorching new space odyssey". Guardian.

- Raphael, Amy (January 6, 2011). Danny Boyle: Authorised Edition. Faber & Faber. p. 166. ISBN 978-0-571-25537-5.

Sometimes you openly acknowledge the influence of other films: in Sunshine, Pinbacker's name is taken from Sgt Pinback in John Carpenter's Dark Star.

- Gus Sorola (March 21, 2012). "Rooster Teeth Podcast". roosterteeth.com (Podcast). Rooster Teeth Productions. Event occurs at 33:46. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013.

- HIDEO_KOJIMA [@HIDEO_KOJIMA_EN] (July 5, 2015). ""Donna-san's iDROID computer voice in MGSV wasn't inspired from HAL9000 in 2001 A Space Odyssey but the female computer voice in Dark Star" (Tweet). Retrieved July 30, 2015 – via Twitter.

- Deusner, Stephen M. (October 11, 2004). "Pinback: Summer in Abaddon". Pitchfork. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

Even the name Pinback – taken from the sci-fi movie Dark Star – suggests something mechanical, like a wind-up robot.

- McConville, Davo (February 27, 2014). "John Carpenter Talks About Composing the Terrifying Scores for His Films". Noisey. Vice Media. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

So I went out to his apartment and basically recorded the score on this… it was very, very primitive. We did the whole thing in about four hours.

- Conrich, Ian; Woods, David (2004). The Cinema of John Carpenter: The Technique of Terror. Wallflower Press. pp. 51–55. ISBN 978-1-904764-14-4.

- Hartmeier, Daniel. "Dark Star – Benson, Arizona". Benzedrine. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

Further reading

- Holdstock, Robert. Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, Octopus Books, 1978, pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-7064-0756-3

- Cinefex magazine, issue 2, Aug 1980. Article by Brad Munson: "Greg Jein, Miniature Giant". (Discusses Dark Star, among other subjects.)

- Fantastic Films magazine, Oct 1978, vol. 1 no. 4, pages 52–58, 68–69. James Delson interviews Greg Jein, about Dark Star and other projects Jein had worked on.

- Fantastic Films magazine, Sep 1979, issue 10, pages 7–17, 29–30. Dan O'Bannon discusses Dark Star and Alien, other subjects. (Article was later reprinted in "The very best of Fantastic Films", Special Edition #22 as well.)

- Fantastic Films magazine, Collector's Edition #17, Jul 1980, pages 16–24, 73, 76–77, 92. (Article: "John Carpenter Overexposed" by Blake Mitchell and James Ferguson. Discusses Dark Star, among other things.)

- Bradbury, Ray, Kaleidoscope Doubleday & Company 1951

- Foster, Alan Dean. Dark Star, Futura Publications, 1979. ISBN 0-7088-8048-7. (Adapted from the script by Dan O'Bannon and John Carpenter)

External links

- Dark Star at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Dark Star at IMDb

- Dark Star at the TCM Movie Database

- Dark Star at AllMovie

- Dark Star at Rotten Tomatoes

- Dark Star at The Official John Carpenter

- Dark Star at the British Film Institute