David Bowie (1969 album)

David Bowie (commonly known as Space Oddity)[lower-alpha 1] is the second studio album by English musician David Bowie. After the commercial failure of his 1967 self-titled debut album, Bowie acquired a new manager, Kenneth Pitt, who commissioned a promotional film in hopes of widening his audience. For the film, Bowie wrote a new song, "Space Oddity", a tale about a fictional astronaut. The song earned Bowie a contract with Mercury Records, who agreed to finance production of a new album, with Pitt hiring Tony Visconti to produce. Due to his dislike of "Space Oddity", Visconti appointed engineer Gus Dudgeon to produce a re-recording for release as a single, while he produced the rest of the album.

| David Bowie | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

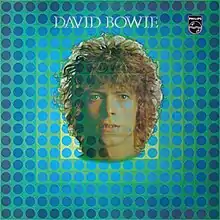

1969 UK release | ||||

| Studio album by | ||||

| Released | 14 November 1969 | |||

| Recorded | 20 June, 16 July – 6 October 1969 | |||

| Studio | Trident, London | |||

| Genre | ||||

| Length | 45:13 | |||

| Label | Philips | |||

| Producer | ||||

| David Bowie chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from David Bowie | ||||

| ||||

| Alternative cover | ||||

1969 US release by Mercury Records | ||||

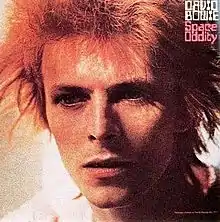

| Alternative cover | ||||

1972 release by RCA Records | ||||

Recording for the new album began in June 1969 and continued until early October, taking place at Trident Studios in London. It featured an array of collaborators, including Herbie Flowers, Rick Wakeman, Terry Cox and the band Junior's Eyes. Departing from the music hall style of his 1967 debut, the record instead features songs influenced by folk rock and psychedelic rock. Lyrically, the songs contain themes that were influenced by numerous events happening in Bowie's life at the time, including former relationships and festivals he attended. Released as a single in July, "Space Oddity" peaked at No. 5 in the UK later in the year, earning Bowie his first commercial hit.

David Bowie was released in the UK on 14 November 1969 by Mercury affiliate Philips Records. For its US release, Mercury retitled it Man of Words/Man of Music and used different artwork. Due to a lack of promotion, the album was a commercial failure, despite earning some positive reviews from music critics. Following Bowie's commercial breakthrough with Ziggy Stardust in 1972, RCA Records reissued the album under the title Space Oddity, and used a contemporary photo of Bowie as the artwork. The reissue managed to chart in both the UK and the US.

Retrospectively, David Bowie has received mixed reviews from critics and biographers, with many criticising the record's lack of cohesiveness. Bowie himself later stated that the record lacked musical direction. Debate continues as to whether the record should stand as Bowie's first "proper" album. The record has been reissued numerous times, with bonus tracks and variance on the inclusion of the hidden track "Don't Sit Down". Labels have used both David Bowie and Space Oddity as the title at different times, with Space Oddity being used for its 2019 remix by Visconti.

Background

After a string of unsuccessful singles, Bowie released his music hall-influenced self-titled debut album through Deram Records in 1967. It was a commercial failure and did little to gain him notice, becoming his last release for two years.[2][3] Around this time he also acquired a new manager, Kenneth Pitt.[4] In 1968, Bowie began a relationship with dancer Hermione Farthingale,[5] which lasted until February 1969.[6] After the commercial failure of David Bowie, Pitt authorised a promotional film in an attempt to introduce Bowie to a larger audience. The film, Love You till Tuesday, went unreleased until 1984,[7] and marked the end of Pitt's mentorship to Bowie.[6]

Knowing the Love You till Tuesday film wouldn't feature any new material, Pitt asked Bowie to write something new.[8] Encompassing the feeling of alienation, Bowie wrote "Space Oddity", a tale about a fictional astronaut named Major Tom.[9] Its title and subject matter were influenced by Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey,[10] which opened in May 1968.[11] Demoed as early as January 1969, "Space Oddity" was finalised and recorded on 2 February at Morgan Studios in London. The session was produced by Jonathan Weston and featured Bowie and guitarist John "Hutch" Hutchinson on co-lead vocals. This version appears in the Love You till Tuesday film.[12] In April, Bowie and Hutchinson recorded demos of tracks that would appear on David Bowie, including another demo of "Space Oddity", "Janine", "An Occasional Dream", "Letter to Hermione" (titled "I'm Not Quite"), and "Cygnet Committee" (titled "Lover to the Dawn").[6]

When Bowie met Angela Barnett in late 1968, she was dating Lou Reizner, the head of Mercury Records in London. After meeting Bowie, Angela consulted with Mercury's Assistant European Director of A&R, Calvin Mark Lee, whom she met through Reizner, to secure Bowie a contract with Mercury.[6] Lee, after hearing "Space Oddity", knew that the record was his chance to get Bowie signed, so Lee went behind Reizner's back to finance a demo session. Lee told biographer Marc Spitz: "We had to do it all behind Lou's back. But it was such a good record."[13] Pitt, unaware of these proceedings, attempted to earn Bowie a contract with other labels, including Atlantic Records in March 1969.[6] On 14 April, at Bowie's request, Pitt met with Simon Hayes, Mercury's New York director, and screened him the Love You till Tuesday film with Lee. In 2009, Lee stated that the reason Bowie earned a contract with Mercury was because of Hayes.[14] Bowie's new contract, enacted in May 1969, allowed Bowie enough finances to make a new album, with two one-year renewal options. The new album would be distributed through Mercury in the US and its affiliate Philips Records in the UK.[15]

Recording

After failing to get George Martin, Pitt hired Tony Visconti, who produced Bowie's later Deram sessions, to produce. Before recording for the album commenced, "Space Oddity" had been selected as the lead single.[16] However, Visconti saw it as a "novelty record" and passed the production responsibility for the song on to Bowie's former engineer Gus Dudgeon.[17] Dudgeon later recalled: "I listened to the demo and thought it was incredible. I couldn't believe that Tony didn't want to do it...he said, 'That's great, you do that and the B-side, and I'll do the album.' I was only too pleased."[16] In an interview with Mary Finnigan for IT in 1969, Bowie compared the two producers:

"Gus is the technician, the arch 'mixer'. He listens to music and says, 'Yes, I like it – it's a groove.' His attitudes to music are very different from a lot of people in the business. With Tony Visconti, who's producing my LP, it's part of his life. He lives with music all day long, it's going on in his room, he writes it, arranges it, produces it, plays it, thinks it, and believes very much in its spiritual source – his whole life is like this."[16]

Recording for David Bowie officially began on 20 June 1969 at Trident Studios in London, where work commenced on the new version of "Space Oddity" and its B-side "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud";[16] Mercury insisted the single be released in a month's time, ahead of the Apollo 11 moon landing.[18] The lineup consisted of Bowie, bassist Herbie Flowers, Rick Wakeman, who played Mellotron, drummer Terry Cox, Junior's Eyes guitarist Mick Wayne, and an orchestra arranged by Paul Buckmaster.[16][18] After the release of the "Space Oddity" single on 11 July, recording continued on 16 July, with work commencing on "Janine", "An Occasional Dream" and "Letter to Hermione"; Work on "Janine" and "An Occasional Dream" continued into 17 July. With Visconti producing, he recruited the Junior's Eyes band – guitarists Tim Renwick and Mick Wayne, bassist John Lodge and drummer John Cambridge (but without vocalist Graham Kelly) – as the main backing band for the sessions;[19] Bowie hired Keith Christmas as an additional guitarist. Also joining the sessions as an engineer was Ken Scott, who recently finished multiple works with the Beatles.[16] Regarding Bowie's attitude towards the recording sessions, Renwick recalled that the band found him "kind of nervous and unsure of himself", further stating that he was vague and gave little direction throughout the sessions. Biographer Paul Trynka attributes the lack of direction to the numerous events happening in Bowie's personal life at the time. On the other hand, Visconti remained enthusiastic during the sessions despite having little production experience at the time: "I was not a very good producer yet and I hadn't started to engineer. I had only made the first Tyrannosaurus Rex album and the Junior's Eyes album," he later stated.[20]

Recording continued on and off for the next few months. On 3 August, Bowie received the news that his father, John Jones, was seriously ill; he died two days later. Bowie wrote "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" to express grief.[21] On 16 August, Bowie participated in the Beckenham Free Festival, commemorating "Memory of a Free Festival" after it. Biographer Nicholas Pegg writes that around this time, Bowie's "disillusion" with the "slack attitude" of hippies around him caused him to reshape the lyrics of "Cygnet Committee".[21] On 8 September, the band began recording for "Memory of a Free Festival". Three days later, recording for "God Knows I'm Good" was attempted at Pye Studios on Marble Arch, but scrapped due to problems with the recording equipment. The song was re-recorded at Trident on 16 September, with Christmas joining on guitar. Recording officially finished on 6 October 1969.[22]

Music and lyrics

The music on David Bowie has been described as folk rock and psychedelic rock,[23][24] with elements of country and progressive rock.[25] Biographer David Buckley writes that "Bowie was still reflecting the governing ideologies of the day and the dominant musical modes...rather than developing a distinct music of his own."[25] Kevin Cann finds the musical ground on the record to encompass "a fusion of acoustic folk leanings with a growing interest in electric rock". Cann continues that the album marking a turning point for the artist, in that lyrically he began "drawing on life" rather than writing "winsome stories".[26] Spitz considers the album to be Bowie's first "heavy" record and also one of his darkest, due to the death of his father. He writes that it reflects the artist's "darkening vision" and depicts "a man coming of age in a world that is increasingly depraved and barren."[27] Susie Goldring of BBC Music calls it a "kaleidoscopic album [that] is an amalgamation of [Bowie's] obsessions – directors, musicians, poets and spirituality of a distinctly late-60s hue."[28]

"Space Oddity" was a largely acoustic number augmented by the eerie tones of the composer's Stylophone, a pocket electronic organ. Some commentators have also seen the song as a metaphor for heroin use, citing the opening countdown as analogous to the drug's passage down the needle prior to the euphoric 'hit', and noting Bowie's admission of a "silly flirtation with smack" in 1968.[29] "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" reflected a strong Bob Dylan influence,[30] with its harmonica, edgy guitar sound and snarling vocal. Spitz describes it as an "extensive hard rock jam",[27] while Buckley calls it a "country-meets-prog-rock collision of ideas."[31] Heard at the end of that track on the UK Philips LP was "Don't Sit Down", an unlisted 40-second jam. The hidden track was excluded from the US Mercury release of the album.[32] Author Peter Doggett criticises its inclusion, calling it "pointless and disruptive", and believes "the album is stronger without it."[33]

"Letter to Hermione" was a farewell ballad to Bowie's former girlfriend, Hermione Farthingale, who was also the subject of "An Occasional Dream",[23] a gentle folk tune reminiscent of the singer's 1967 debut album. "God Knows I'm Good", Bowie's observational tale of a shoplifter's plight, also recalled his earlier style.[23]

"Cygnet Committee" has been called Bowie's "first true masterpiece".[34] Commonly regarded as the album track most indicative of the composer's future direction, its lead character is a messianic figure "who breaks down barriers for his younger followers, but finds that he has only provided them with the means to reject and destroy him".[23] Bowie himself described it at the time as a put down of hippies who seemed ready to follow any charismatic leader.[34] "Janine" was written about a girlfriend of George Underwood.[35] It has been cited as another track that foreshadowed themes to which Bowie would return in the 1970s, in this case the fracturing of personality, featuring the words "But if you took an axe to me, you'd kill another man not me at all".[17]

The Buddhism-influenced "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" was presented in a heavily expanded form compared to the original guitar-and-cello version on the B-side of the "Space Oddity" single; the album cut featured a 50-piece orchestra. "Memory of a Free Festival" was Bowie's reminiscence of an arts festival he had organised in August 1969. Its drawn-out fade/chorus ("The Sun Machine is coming down / And we're gonna have a party") was compared to the Beatles' "Hey Jude";[36] the song has also been interpreted as a derisive comment on the counterculture it was ostensibly celebrating.[37] The background vocals for the crowd finale featured Bob Harris, his wife Sue, Tony Woollcott and Marc Bolan.[38]

"Conversation Piece," an outtake from the album sessions, which has been described as featuring "a lovely melody and an emotive lyric addressing familiar Bowie topics of alienation and social exclusion," was released for the first time as a single B-side in 1970.[39]

Title and packaging

In the UK, the record was released under the eponymous title David Bowie,[40] the same title as Bowie's 1967 debut for Deram Records, a move which Trynka calls "bizarre".[41] The original UK cover artwork featured a facial portrait of Bowie taken by British photographer Vernon Dewhurst exposed on top of a work by Hungarian artist Victor Vasarely with blue and violet spots on a green background. The artwork, titled CTA 25 Neg, was designed by Bowie and Calvin Mark Lee, who enthusiastically collected Vasarely's works; Lee is credited as CML33. The back cover was an illustration by Bowie's childhood friend George Underwood and depicted lyrical aspects from the album, stylistically similar to the 1968 Tyrannosaurus Rex album My People Were Fair and Had Sky in Their Hair... But Now They're Content to Wear Stars on Their Brows.[42][21] Underwood's illustration was based on an initial sketches by Bowie. According to Underwood, the sketches included "a fish in water, two astronauts holding a rose, [and] rats in bowler hats representing the Beckenham Arts Lab committee types he was so pissed off with."[21] Pegg writes that these items appear in the final picture, along with "a Buddha, a smouldering joint, an unmistakable portrait of Hermione Farthingale, and a weeping woman (presumably the shoplifter in "God Knows I'm Good") being comforted by a Pierrot", which he notes is "remarkably similar in appearance" to the "Ashes to Ashes" character Bowie later adopted.[21] Underwood's illustration is referred to on the album sleeve as Depth of a Circle, which according to Bowie was a typo by the record label; he intended it to read Width of a Circle, a title he used for a song on his next album.[42][21] Apart from Bowie, none of the musicians who played on the album were credited on the original pressings, due to the majority being under contract with other labels in the UK; song lyrics were instead presented on the inner gatefold sleeve.[42]

For the US release in 1970, the album was retitled Man of Words/Man of Music,[43] although Cann writes that this phrase was added to the cover to describe the artist and was not intended to replace the title.[42] Mercury also changed Vasarely's artwork in favour of a different, but similar photograph by Dewhurst, placed against a plain blue background. Cann criticises this artwork, stating that it "suffered from sloppy technical application and the image appeared washed out as a result of poor duplication of the transparency."[42] However, the musicians were credited on this release, while song lyrics still appeared on the inner gatefold. Drummer John Cambridge later said in 1991: "[Bowie] showed me a copy; I was really pleased to see I was credited inside. I kept on to [Bowie] to let me have it and he kept saying 'It's my only copy.' Eventually he gave in and gave it to me. I've still got it."[42]

As part of a reissue campaign undertaken by RCA Records in the wake of the commercial breakthrough of Ziggy Stardust, the album was repackaged in 1972 with the title Space Oddity, after the title track.[lower-alpha 2] For this release, the front cover was updated with a new photograph of Bowie taken the same year by photographer Mick Rock at Haddon Hall. The sleeve notes proclaimed that the album ""was NOW then, and it is still now NOW: personal and universal, perhaps galactic, microcosmic and macrocosmic."[43]

Rykodisc's 1990 reissue, again titled Space Oddity, used the 1972 front cover photograph as its cover, while also incorporating a reproduction of the 1970 US front cover.[44] For the 1999 EMI reissue, the original UK portrait was restored, although the Space Oddity title was retained. EMI's 40th anniversary CD reissue in 2009 and the various releases of the album associated with the 2015 Five Years (1969–1973) box set reverted to the original David Bowie title and kept the UK artwork.[43][45] For the album's 2019 remix, the Space Oddity title was used.[46]

Release

"Space Oddity" was released as a single on 11 July 1969, with "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" as the B-side.[47] Featuring different edits between the British and American versions, it was rush-released by the label – it was recorded only three weeks prior – as a way to capitalise on the Apollo 11 moon landing.[48] Although it received some glowing reviews, the single initially failed to sell, despite attempts made by Pitt at chart-rigging.[49] By September however, the single debuted on the UK Singles Chart at No. 48, slowing rising to No. 5 by early November.[48][49] Mercury's publicist Ron Oberman wrote a letter to American journalists describing "Space Oddity" as "one of the greatest recordings I've ever heard. If this already controversial single gets the airplay, it's going to be a huge hit." Despite this, the single flopped completely in the US, which Pitt attributed to Oberman's use of the word "controversial" in his statement, which caused it to be banned on multiple radio stations across America. The single's success in the UK earned Bowie a number of television appearances throughout the rest of the year, including his first appearance on Top of the Pops in early October.[50]

David Bowie was released in the UK on 14 November 1969 by Philips Records,[lower-alpha 3][52] with the catalogue number SBL 7912.[53] Cann states that Mercury considered releasing "Janine" as a follow-up single to "Space Oddity", but were uncertain about its commercial appeal and scrapped it.[54] Biographer Christopher Sandford writes that despite the commercial success of "Space Oddity", the remainder of the album bore little resemblance to it and resulted in it being a commercial failure on its initial release.[36] Furthermore, around the same time as the album's release, personnel at Philips Records underwent numerous changes, some of whom were Bowie's supporters, resulting in a severe lack of promotion for the album. Despite Bowie being named 1969's Best Newcomer in a readers' poll for Music Now!, and "Space Oddity" being named record of the year by Penny Valentine of Disc and Music Echo, the album barely sold over 5,000 copies by March 1970.[51] Following the 1972 reissue by RCA, the album finally managed to chart, peaking at No. 17 on the UK Albums Chart in November 1972, remaining on the chart for 42 weeks.[55] It also peaked at No. 16 on the US Billboard 200 in April 1973, remaining on the chart for 36 weeks.[56] The album's 1990 reissue also managed to chart at No. 64 in the UK.[55]

Critical reception

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Classic Rock | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| Pitchfork | 6.7/10[60] |

| PopMatters | |

| Record Collector | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

Upon release, the album received primarily mixed reviews from journalists.[64] Penny Valentine of Disc and Music Echo gave the album a positive review, describing it as "rather doomy and un-nerving, but Bowie's point comes across like a latter-day Dylan. It is an album a lot of people are going to expect a lot from. I don't think they'll be disappointed."[21] A reviewer for Music Now! offered similar praise, calling it "Deep, thoughtful, probing, exposing, gouging at your innards" and concluded: "This is more than a record. It is an experience. An expression of life as others see it. The lyrics are full of the grandeur of yesterday, the immediacy of today and the futility of tomorrow. This is well worth your attention."[21] Nancy Erlich of The New York Times, in a review published over a year after the album's release, praised the album, calling it, "a complete, coherent and brilliant vision".[65] Other reviewers offered more mixed sentiments. A writer for Music Business Weekly found that "Bowie seems to be a little unsure of the direction he is going in", criticising the various musical styles found throughout, ultimately describing the record as "over ambitious".[21] A reviewer for Zygote praised "Space Oddity" and "Memory of a Free Festival", but felt the album as a whole lacked cohesiveness and was "very awkward to the ear". The reviewer concluded that "Bowie is erratic. When he succeeds, he's excellent; when fails, he's laborious."[66] Village Voice critic Robert Christgau considered this album, along with Bowie's follow-up, The Man Who Sold the World, to be "overwrought excursions".[67]

Retrospectively, the album has continued to receive primarily mixed reviews from reviewers, with many criticising its lack of cohesiveness. Dave Thompson of AllMusic felt that although the record has its moments, he writes that: "'Space Oddity' aside, Bowie possessed very little in the way of commercial songs, and the ensuing album (his second) emerged as a dense, even rambling, excursion through the folky strains that were the last glimmering of British psychedelia."[57] Douglas Wolk of Pitchfork found that Bowie presented numerous ideas throughout the record, but didn't know what to do with them, writing, "he wears his influences on his sleeve and constantly overreaches for dramatic effect."[60] Terry Staunton of Record Collector agreed, writing: "Space Oddity may be regarded as the singer's first 'proper' album, though its mish-mash of styles and strummy experiments suggest he was still trying to settle on an identity."[62] The album's 40th anniversary remaster garnered numerous reviews. Mike Schiller of PopMatters stated that although it's far from Bowie's best, the record as a whole is "not half bad". Despite its flaws, Schiller considers the record a "landmark" in Bowie's catalogue, writing that "it offers a glimpse at a man transitioning into the artist we've come to know".[61] Stuart Berman of Pitchfork found that the record's "prog-folk hymnals" were a precursor to the "artful glam rock" sound that made Bowie a star.[68] Reviewing for The Quietus, John Tatlock found that the album is not where "it all came together", primarily due to a lack of coherence. Tatlock also believed it to not stand out on its own merit, but nonetheless, states that "it captures its creator at a fascinating crossroads, and is much more than a fans-only curio."[69]

Aftermath and legacy

Following the release of the album, Bowie spent the next month promoting the record through live performances and interviews.[70] In mid-December 1969, Philips requested a new version of "Space Oddity" with Italian lyrics upon learning one had already been recorded in Italy. The Italian version was recorded on 20 December at Morgan Studios in London, with accent coach and producer Claudio Fabi producing and lyrics translated by Italian lyricist Mogol. This version, titled "Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola" (meaning "Lonely Boy, Lonely Boy"[49]), was released as a single in Italy in 1970 and failed to chart.[64][50]

In January 1970, Bowie began arrangements to re-record an older Deram-era composition, "London Bye Ta-Ta", along with a new composition, "The Prettiest Star". Recording for both tracks began at Trident on 7 January and continued on 13 January, completing on two days later. Guitar work was provided by Marc Bolan on "The Prettiest Star".[71][72] "London Bye Ta-Ta" was initially chosen as the follow-up single to "Space Oddity" but at the last minute, Bowie chose "The Prettiest Star" against Pitt's wishes. Released as a single on 6 March 1970, with the outtake "Conversation Piece" as the B-side,[73] "The Prettiest Star" received praise from music journalists,[74] but failed to chart.[75]

Following the commercial failure of "The Prettiest Star", the label requested the follow-up to be a re-recording of the Space Oddity track "Memory of a Free Festival", to be split across and A- and B-sides.[76] The two-part single was released on 26 June and again, failed to chart.[77][78] By this time, Bowie had completed recording his follow-up record The Man Who Sold the World,[79] which marked a shift in musical style towards hard rock.[80] Around the same time, due to continuing managerial disputes, Bowie terminated his contract with Pitt and hired a new manager, Tony Defries.[81]

– David Bowie describing the album in the BBC documentary Golden Years, 2000

Biographers have differing views on the album. While Buckley calls it "the first Bowie album proper",[31] NME editors Roy Carr and Charles Shaar Murray have said, "Some of it belonged in '67 and some of it in '72, but in 1969 it all seemed vastly incongruous. Basically, David Bowie can be viewed in retrospect as all that Bowie had been and a little of what he would become, all jumbled up and fighting for control..."[23] Trynka similarly states that the record has an "endearing lack of artifice", which nonetheless makes it an "unique" entry in the artist's catalogue.[82] Pegg calls the album "a remarkable step forward from anything Bowie had recorded before."[51] He writes that a few of the tracks, including "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed", "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" and "Cygnet Committee", highlight Bowie's evolution as a lyricist. However, he ultimately believes that the "monolithic reputation" of "Space Oddity" does the album more harm than good.[51] Spitz opinions that "while not iconic, as his seventies albums would become, Space Oddity is first-rate as trippy rock records go."[83] Sandford writes that "Space Oddity" aside, the record didn't have a "voice", and also lacked "punch" and "clarity". He continues that the songs vary between "mundane" (highlighting the two tributes to Farthingale) and "mawkish" (highlighting "God Knows I'm Good"). However, he further stated that the record, like his 1967 debut, did have its moments, signaling out "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" and "Janine".[36]

Track listing

All tracks are written by David Bowie.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Space Oddity" | 5:16 |

| 2. | "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" | 6:55[lower-alpha 4] |

| 3. | "Letter to Hermione" | 2:33 |

| 4. | "Cygnet Committee" | 9:35 |

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Janine" | 3:25 |

| 2. | "An Occasional Dream" | 3:01 |

| 3. | "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" | 4:52 |

| 4. | "God Knows I'm Good" | 3:21 |

| 5. | "Memory of a Free Festival" | 7:09 |

- 1990 bonus tracks[53]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Conversation Piece" (Single B-side of "The Prettiest Star", 1970) | 3:05 |

| 2. | "Memory of a Free Festival Part 1" (Single version A-side, 1970) | 3:59 |

| 3. | "Memory of a Free Festival Part 2" (Single version B-side, 1970) | 3:31 |

- 2009 bonus disc[84]

All tracks are written by David Bowie, except "Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola": music by Bowie, lyrics by Mogol.

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Space Oddity" (Demo version) | 5:10 |

| 2. | "An Occasional Dream" (Demo version) | 2:49 |

| 3. | "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" (B-side of "Space Oddity", 1969) | 4:56 |

| 4. | "Brian Matthew interviews David / "Let Me Sleep Beside You" (BBC Radio session D.L.T. (Dave Lee Travis Show), 1969) | 4:45 |

| 5. | "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" (BBC Radio session D.L.T. Show, 1969) | 3:54 |

| 6. | "Janine" (BBC Radio session D.L.T. Show, 1969) | 3:02 |

| 7. | "London Bye Ta–Ta" (Stereo version) | 3:12 |

| 8. | "The Prettiest Star" (Stereo version) | 3:12 |

| 9. | "Conversation Piece" (Stereo version) | 3:06 |

| 10. | "Memory of a Free Festival (Part 1)" (Single A-side) | 4:01 |

| 11. | "Memory of a Free Festival (Part 2)" (Single B-side) | 3:30 |

| 12. | "Wild Eyed Boy from Freecloud" (Alternate album mix) | 4:45 |

| 13. | "Memory of a Free Festival" (Alternate album mix) | 9:22 |

| 14. | "London Bye Ta–Ta" (Alternate stereo mix) | 2:34 |

| 15. | "Ragazzo solo, ragazza sola" (Full-length stereo version) | 5:14 |

Reissues

Space Oddity was first released on CD by RCA in 1984. In keeping with the 1970 Mercury release and the 1972 RCA reissue, "Don't Sit Down" remained missing. The German (for the European market) and Japanese (for the US market) masters were sourced from different tapes and are not identical for each region. In 1990, the album was reissued by Rykodisc/EMI with "Don't Sit Down" included as an independent song and three bonus tracks.[53][85] The album was reissued again in 1999 by EMI/Virgin, without bonus tracks but with 24-bit digitally remastered sound and again including a separately listed "Don't Sit Down".[86] The Japanese mini LP replicates the cover of the original Philips LP.

In 2009, the album was released as a remastered 2-CD special edition by EMI/Virgin with a second bonus disc compilation of unreleased demos, stereo versions and previously released B-sides and BBC session tracks. "Don't Sit Down" reverted to its status as a hidden track.[84] The 2009 remaster of the album became available on vinyl for the first time in June 2020, in a picture disc release (with artwork based on the 1972 RCA reissue).[87] In 2015, the album was remastered for the Five Years (1969–1973) box set.[45][88] It was released in CD, vinyl, and digital formats, both as part of this compilation and separately.[89]

In 2019, the album was remixed and remastered by Tony Visconti, and released in the CD boxed set Conversation Piece, as well as being made available separately in CD, vinyl, and digital formats. The new version of the album added the outtake "Conversation Piece" to the regular sequencing of the album for the first time, while omitting "Don't Sit Down".[46][90][91]

Personnel

Album credits per the 2009 reissue liner notes and biographer Nicholas Pegg.[92][93]

- David Bowie – vocals, acoustic guitar, stylophone ("Space Oddity"), chord organ ("Memory of a Free Festival"), kalimba

- Tim Renwick – electric guitar, flute, recorder

- Keith Christmas – acoustic guitar

- Mick Wayne – guitar

- Rick Wakeman – Mellotron, electric harpsichord

- Tony Visconti – bass guitar, flute, recorder

- Herbie Flowers – bass guitar

- John "Honk" Lodge – bass guitar

- John Cambridge – drums

- Terry Cox – drums

- Benny Marshall and friends – harmonica, backing vocals ("Memory of a Free Festival")

- Paul Buckmaster – cello

- Production

- Tony Visconti – producer

- Gus Dudgeon – producer ("Space Oddity")

Charts

| Year | Chart | Peak Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1972 | UK Albums (OCC)[94] | 17 |

| 1972 | Australian Albums (Kent Music Report)[95] | 21 |

| 1972 | Finnish Albums | 27 |

| 1973 | Canadian Albums (RPM)[96] | 13 |

| 1973 | Spanish Albums (Promusicae)[97] | 8 |

| 1973 | US Billboard 200[98] | 16 |

| 2016 | French Albums (SNEP)[99] | 105 |

| 2016 | Italian Albums (FIMI)[100] | 60 |

| 2016 | Swiss Albums (Schweizer Hitparade)[101] | 66 |

| 2019 | Spanish Albums (PROMUSICAE)[102] | 68 |

| 2020 | Belgian Albums (Ultratop Flanders)[103] | 60 |

| 2020 | Belgian Albums (Ultratop Wallonia)[104] | 132 |

| 2020 | German Albums (Offizielle Top 100)[105] | 63 |

Release history

| Region | Date | Title | Label | Format | Catalogue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | 14 November 1969[52] | David Bowie | Philips | Stereo LP | SBL 7912 |

| USA | 1970 | Man of Words/Man of Music | Mercury | Stereo LP | SR 61246 |

| USA | 1972 | Space Oddity | RCA | Stereo LP | LSP 4813 |

Notes

- Biographer Nicholas Pegg, in his book The Complete David Bowie, refers to the album as Space Oddity throughout. He states that following its 1972 reissue, the album was not referred to again as David Bowie until its 2009 reissue, meaning Space Oddity was its official title for almost forty years. Pegg further states that this differentiates it from Bowie's 1967 self-titled debut album.[1]

- In Spain, the album was retitled Odisea Espacial (Spanish for "Space Odyssey").[43]

- The album's US release by Mercury Records is disputed. Doggett gives the US release date as January 1970,[33] while Pegg gives a release date of February 1970.[51]

- The 6:55 track length of "Unwashed and Somewhat Slightly Dazed" refers to the original UK LP release and includes "Don't Sit Down".

References

- Pegg 2016, p. 12.

- Cann 2010, pp. 106–107.

- Sandford 1997, pp. 41–42.

- Sandford 1997, pp. 38–39.

- Sandford 1997, p. 46.

- Pegg 2016, p. 334.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 636–638.

- O'Leary 2015, pp. 115–116.

- Pegg 2016, p. 255.

- Doggett 2012, p. 59.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 116.

- Pegg 2016, p. 256.

- Spitz 2009, p. 106.

- Cann 2010, p. 150.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 334–335.

- Pegg 2016, p. 335.

- Buckley 1999, pp. 36–79.

- Cann 2010, p. 153.

- Cann 2010, p. 155.

- Trynka 2011, pp. 115–116.

- Pegg 2016, p. 336.

- Cann 2010, pp. 156–163.

- Carr & Murray 1981, pp. 28–29.

- Carlick, Stephen (9 March 2016). "David Bowie Fantastic Voyage". Exclaim!. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- Buckley 2005, pp. 64–65.

- Cann 2010, pp. 169–170.

- Spitz 2009, p. 124.

- Goldring, Susie (2007). "Review of David Bowie – Space Oddity". BBC Music. Archived from the original on 29 October 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 255–260.

- Pegg 2016, p. 295.

- Buckley 2005, p. 65.

- Cann 2010, pp. 170, 275.

- Doggett 2012, p. 80.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 67–68.

- Cann 2010, p. 170.

- Sandford 1997, p. 60.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 182–184.

- Cann 2010, pp. 170–171.

- Pegg 2016, p. 64.

- Sandford 1997, p. 57.

- Trynka 2011, p. 121.

- Cann 2010, p. 171.

- Pegg 2016, p. 338.

- David Bowie (CD liner graphics). David Bowie. UK & Europe: EMI. 1990. CDP 79 1835 2.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Five Years (1969–1973) (Box set liner notes). David Bowie. UK, Europe & US: Parlophone. 2015. DBXL 1.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Kreps, Daniel (5 September 2019). "David Bowie Box Set Collects Early Home Demos, 'Space Oddity' 2019 Mix". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 24 November 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- O'Leary 2015, p. 496.

- Pegg 2016, p. 257.

- Buckley 2005, p. 62.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 257–258.

- Pegg 2016, p. 337.

- Cann 2010, pp. 167–168.

- Pegg 2016, p. 333.

- Cann 2010, p. 172.

- "Space Oddity – Full Official Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "Space Oddity Chart History". Billboard. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Thompson, Dave. "Space Oddity – David Bowie". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 December 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Wall, Mick (November 2009). "David Bowie – Space Oddity 40th Anniversary Edition". Classic Rock. No. 138. p. 98.

- Larkin, Colin (2011). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (5th concise ed.). Omnibus Press.

- Wolk, Douglas (1 October 2015). "David Bowie: Five Years 1969–1973 Album Review". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 6 February 2016. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Schiller, Mike (16 December 2009). "David Bowie: Space Oddity (40th anniversary edition)". PopMatters. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 10 August 2017.

- Staunton, Terry. "David Bowie – Space Oddity: 40th anniversary edition". Record Collector. Archived from the original on 3 March 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Sheffield 2004, pp. 97–98.

- Cann 2010, p. 174.

- Erlich, Nancy (11 July 1971). "TimesMachine: Bowie, Bolan, Heron -- Superstars?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 June 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 337–338.

- "Robert Christgau: CG: david bowie". Archived from the original on 13 January 2016. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- Berman, Stuart (17 November 2009). "David Bowie: Space Oddity [40th Anniversary Edition]". Pitchfork. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Tatlock, John (16 October 2009). "David Bowie: Space Oddity 40th Anniversary Edition". The Quietus. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Cann 2010, pp. 172–174.

- Cann 2010, p. 178.

- Pegg 2016, pp. 169, 212.

- Cann 2010, p. 185.

- Pegg 2016, p. 212.

- Spitz 2009, pp. 131–132.

- Cann 2010, pp. 188–190.

- Cann 2010, p. 196.

- Pegg 2016, p. 183.

- Cann 2010, pp. 191–193.

- Doggett 2012, p. 106.

- Cann 2010, pp. 188, 191.

- Trynka 2011, p. 123.

- Spitz 2009, p. 126.

- David Bowie (CD liner notes). David Bowie. UK & Europe/US: EMI/Virgin. 2009. 50999-307522-2-1.CS1 maint: others (link)

- David Bowie (CD liner notes). David Bowie. UK & Europe: EMI. 1990. CDP 79 1835 2.CS1 maint: others (link)

- David Bowie (CD liner notes). David Bowie. UK & Europe/US: EMI/Virgin Records. 1999. 7243 521898 0 9.CS1 maint: others (link)

- David Bowie / Space Oddity album issued as vinyl picture disc Archived 12 April 2020 at the Wayback Machine at superdeluxeedition.com

- "Five Years 1969 – 1973 box set due September". David Bowie Official Website. Archived from the original on 18 February 2016. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- Spanos, Brittany (23 June 2015). "David Bowie to Release Massive Box Set 'Five Years 1969–1973'". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 August 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2020.

- Young, Alex (5 September 2019). "New mix of David Bowie's Space Oddity included on upcoming Conversation Piece box set". Consequence of Sound. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Space Oddity (2019 Mix) (CD liner notes). David Bowie. US & Europe: Parlophone. 2019. DBSOCD50.CS1 maint: others (link)

- David Bowie [Space Oddity] (CD booklet). David Bowie. UK & Europe: EMI. 2009. 50999-307522-2-1.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Pegg 2016, pp. 333–334.

- "David Bowie | Artist | Official Charts". UK Albums Chart. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- Kent, David (1993). Australian Chart Book 1970–1992. St Ives, NSW: Australian Chart Book. ISBN 0-646-11917-6.

- "Results – RPM – Library and Archives Canada". Collectionscanada.gc.ca. Archived from the original on 20 October 2012. Retrieved 27 July 2011.

- "Hits of the World – Spain". Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. 14 July 1973. p. 60. Archived from the original on 12 December 2020. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- "David Bowie Chart History (Billboard 200)". Billboard. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "Lescharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Italiancharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Swisscharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Spanishcharts.com – David Bowie – Space Oddity". Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in Dutch). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Ultratop.be – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in French). Hung Medien. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

- "Offiziellecharts.de – David Bowie – Space Oddity" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 24 July 2020.

Sources

- Buckley, David (1999). Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-1-85227-784-0.

- Buckley, David (2005) [1999]. Strange Fascination – David Bowie: The Definitive Story. London: Virgin Books. ISBN 978-0-75351-002-5.

- Cann, Kevin (2010). Any Day Now – David Bowie: The London Years: 1947–1974. Croyden, Surrey: Adelita. ISBN 978-0-95520-177-6.

- Carr, Roy; Murray, Charles Shaar (1981). Bowie: An Illustrated Record. London: Eel Pie Publishing. ISBN 978-0-38077-966-6.

- Doggett, Peter (2012). The Man Who Sold the World: David Bowie and the 1970s. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 978-0-06-202466-4.

- O'Leary, Chris (2015). Rebel Rebel: All the Songs of David Bowie from '64 to '76. Winchester: Zero Books. ISBN 978-1-78099-244-0.

- Pegg, Nicholas (2016). The Complete David Bowie (Revised and Updated ed.). London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-78565-365-0.

- Sandford, Christopher (1997) [1996]. Bowie: Loving the Alien. London: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80854-4.

- Sheffield, Rob (2004). "David Bowie". In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Spitz, Marc (2009). Bowie: A Biography. New York: Crown Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-307-71699-6.

- Trynka, Paul (2011). David Bowie – Starman: The Definitive Biography. New York City: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 978-0-31603-225-4.

External links

- David Bowie at Discogs (list of releases)