Day of the Dead

The Day of the Dead (Spanish: Día de Muertos or Día de los Muertos)[1][2] is a Mexican holiday celebrated in Mexico and elsewhere associated with the Catholic celebrations of All Saints' Day and All Souls' Day, and is held on November 1 and 2. The multi-day holiday involves family and friends gathering to pray for and to remember friends and family members who have died. It is commonly portrayed as a day of celebration rather than mourning.[3] Mexican academics are divided on whether the festivity has indigenous pre-hispanic roots or whether it is a 20th-century rebranded version of a Spanish tradition developed by the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas to encourage Mexican nationalism through an "Aztec" identity.[4][5][6] The festivity has become a national symbol and as such is taught in the nation's school system, typically asserting a native origin.[7] In 2008, the tradition was inscribed in the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.[8]

| Day of the Dead | |

|---|---|

Día de Muertos altar commemorating a deceased man in Milpa Alta, Mexico City | |

| Observed by | Mexico, and regions with large Mexican populations |

| Type | Cultural Catholic (with possible syncretic elements) |

| Significance | Prayer and remembrance of friends and family members who have died |

| Celebrations | Creation of altars to remember the dead, traditional dishes for the Day of the Dead |

| Begins | November 1 |

| Ends | November 2 |

| Date | November 2 |

| Next time | 2 November 2021 |

| Frequency | Annual |

| Related to | All Saints' Day |

The holiday is more commonly called "Día de los Muertos" outside Mexico.[9][10] Whereas in Spain and most of Latin America the public holiday and similar traditions are typically held on All Saints' Day (Todos los Santos), the Mexican government under Cardenas switched the festivity to All Souls' Day (Fieles Difuntos) in an effort to secularize the festivity and distinguish it from the Hispanic Catholic festival.[11]

The Dia de Muertos was then promoted throughout the country as a continuity of ancient Aztec festivals celebrating death, a theory strongly encouraged by Mexican poet Octavio Paz. Traditions connected with the holiday include building home altars called ofrendas, honoring the deceased using calaveras, aztec marigolds, and the favorite foods and beverages of the departed, and visiting graves with these as gifts.[12]

Origin and history

The Dia de Muertos is commonly associated with Mexican pre-hispanic indigenous traditions both in Mexico and abroad. However, over the past decades, Mexican academia has increasingly questioned the validity of this assumption, even going as far as calling it a politically-motivated fabrication. Historian Elsa Malvido, researcher for the Mexican INAH and founder of the institute's Taller de Estudios sobre la Muerte, was the first to do so in the context of her wider research into Mexican attitudes to death and disease across the centuries. Malvido completely discards a native or even syncretic origin arguing that the tradition can be fully traced to Medieval Europe. She highlights the existence of similar traditions on the same day, not just in Spain, but in the rest of Catholic Southern Europe and Latin America such as altars for the dead, sweets in the shape of skulls and bread in the shape of bones.[13]

Agustin Sanchez Gonzalez has a similar view in his article published in the INAH's bi-monthly journal Arqueología Mexicana. Gonzalez states that, even though the "indigenous" narrative became hegemonic, the spirit of the festivity has far more in common with European traditions of Danse macabre and their allegories of life and death personified in the human skeleton to remind us the ephemeral nature of life. He also highlights that in the 19th century press there was little mention of the Day of the Dead in the sense that we know it today. All there was were long processions to cemeteries, sometimes ending with drunkenness. Elsa Malvido, also points to the recent origin of the tradition of "velar" or staying up all night with the dead. It resulted from the Reform Laws under the presidency of Benito Juarez which forced family pantheons out of Churches and into civil cemeteries, requiring rich families having servants guarding family possessions displayed at altars.[14]

Gonzalez further explains that the modern characteristics of the "Dia de Muertos" during the first governments following the Mexican revolution led to a nationalist culture and iconography based on pride all things indigenous - portraying Native Americans as the origin of everything truly Mexican.

The historian Ricardo Pérez Montfort has further demonstrated how the ideology known as indigenismo became more and more closely linked to post-revolutionary official projects whereas Hispanismo was identified with conservative political stances. This exclusive nationalism began to displace all other cultural perspectives to the point that in the 1930s, the Aztec god Quetzalcoatl was officially promoted by the government as a substitute for the Spanish Three Kings tradition, with a person dressed up as the deity offering gifts to poor children.[15]

In this context, the Day of the Dead began to be officially isolated from the Catholic Church by the leftist government of Lazaro Cardenas motivated both by "indigenismo" and left-leaning anti-clericalism. Malvido herself goes as far as calling the festivity a "Cardenist invention" whereby the Catholic elements are removed and emphasis is laid on indigenous iconography, the focus on death and what Malvido considers to be the cultural invention according to which Mexicans venerate death.[16][17] Gonzalez explains that Mexican nationalism developed diverse cultural expressions with a seal of tradition but which are essentially social constructs which eventually developed ancestral tones. One of the these would be the Catholic Día de Muertos which, during the 20th century, appropriated the elements of an ancient pagan rite.[18]

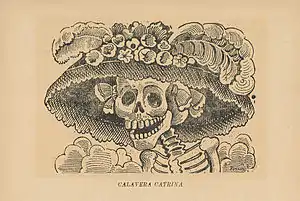

One key element of the re-developed festivity which appears during this time is La Calavera Catrina by Mexican lithographer José Guadalupe Posada. According to Gonzalez, whereas Posada is portrayed in current times as the "restorer" of Mexico's pre-hispanic tradition he was never interested in Native American culture or history. Posada was predominantly interested in drawing scary images which are far closer to those of the European renaissance or the horrors painted by Francisco de Goya in the Spanish war of Independence against Napoleon than the Mexica tzompantli. The recent trans-atlantic connection can also be observed in the pervasive use of couplet in allegories of death and the play Don Juan Tenorio by 19th Spanish writer José Zorrilla which is represented on this date both in Spain and in Mexico since the early 19th century due to its ghostly apparitions and cemetery scenes.[19]

Observance in Mexico

Altars (ofrendas)

People go to cemeteries to be with the souls of the departed and build private altars containing the favorite foods and beverages, as well as photos and memorabilia, of the departed. The intent is to encourage visits by the souls, so the souls will hear the prayers and the comments of the living directed to them. Celebrations can take a humorous tone, as celebrants remember funny events and anecdotes about the departed.[20]

Plans for the day are made throughout the year, including gathering the goods to be offered to the dead. During the three-day period families usually clean and decorate graves;[21] most visit the cemeteries where their loved ones are buried and decorate their graves with ofrendas (altars), which often include orange Mexican marigolds (Tagetes erecta) called cempasúchil (originally named cempōhualxōchitl, Nāhuatl for 'twenty flowers'). In modern Mexico the marigold is sometimes called Flor de Muerto ('Flower of Dead'). These flowers are thought to attract souls of the dead to the offerings. It is also believed the bright petals with a strong scent can guide the souls from cemeteries to their family homes.[22][23]

Toys are brought for dead children (los angelitos, or 'the little angels'), and bottles of tequila, mezcal or pulque or jars of atole for adults. Families will also offer trinkets or the deceased's favorite candies on the grave. Some families have ofrendas in homes, usually with foods such as candied pumpkin, pan de muerto ('bread of dead'), and sugar skulls; and beverages such as atole. The ofrendas are left out in the homes as a welcoming gesture for the deceased.[21][23] Some people believe the spirits of the dead eat the "spiritual essence" of the ofrendas' food, so though the celebrators eat the food after the festivities, they believe it lacks nutritional value. Pillows and blankets are left out so the deceased can rest after their long journey. In some parts of Mexico, such as the towns of Mixquic, Pátzcuaro and Janitzio, people spend all night beside the graves of their relatives. In many places, people have picnics at the grave site, as well.

Some families build altars or small shrines in their homes;[21] these sometimes feature a Christian cross, statues or pictures of the Blessed Virgin Mary, pictures of deceased relatives and other people, scores of candles, and an ofrenda. Traditionally, families spend some time around the altar, praying and telling anecdotes about the deceased. In some locations, celebrants wear shells on their clothing, so when they dance, the noise will wake up the dead; some will also dress up as the deceased.

Food

During Day of the Dead festivities, food is both eaten by living people and given to the spirits of their departed ancestors as ofrendas ('offerings').[24] Tamales are one of the most common dishes prepared for this day for both purposes.[25]

Pan de muerto and calaveras are associated specifically with Day of the Dead. Pan de muerto is a type of sweet roll shaped like a bun, topped with sugar, and often decorated with bone-shaped pieces of the same pastry.[26] Calaveras, or sugar skulls, display colorful designs to represent the vitality and individual personality of the departed.[25]

In addition to food, drink is also important to the tradition of Day of the Dead. Historically, the main alcoholic drink was pulque while today families will commonly drink the favorite beverage of their deceased ancestors.[25] Other drinks associated with the holiday are atole and champurrado, warm, thick, non-alcoholic masa drinks.

Jamaican iced tea is a popular herbal tea made of the flowers and leaves of the Jamaican hibiscus plant (Hibiscus sabdariffa), known as flor de Jamaica in Mexico. It is served cold and quite sweet with a lot of ice. The ruby-red beverage is called hibiscus tea in English-speaking countries and called agua de Jamaica (water of hibiscus) in Spanish.[27]

Calaveras

Those with a distinctive talent for writing sometimes create short poems, called calaveras literarias (skulls literature), mocking epitaphs of friends, describing interesting habits and attitudes or funny anecdotes.[28] This custom originated in the 18th or 19th century after a newspaper published a poem narrating a dream of a cemetery in the future, "and all of us were dead", proceeding to read the tombstones. Newspapers dedicate calaveras to public figures, with cartoons of skeletons in the style of the famous calaveras of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican illustrator.[29] Theatrical presentations of Don Juan Tenorio by José Zorrilla (1817–1893) are also traditional on this day.

Posada created what might be his most famous print, he called the print La Calavera Catrina ("The Elegant Skull") as a parody of a Mexican upper-class female. Posada's intent with the image was to ridicule the others that would claim the culture of the Europeans over the culture of the indigenous people. The image was a skeleton with a big floppy hat decorated with 2 big feathers and multiple flowers on the top of the hat. Posada's striking image of a costumed female with a skeleton face has become associated with the Day of the Dead, and Catrina figures often are a prominent part of modern Day of the Dead observances.[29]

A common symbol of the holiday is the skull (in Spanish calavera), which celebrants represent in masks, called calacas (colloquial term for skeleton), and foods such as sugar or chocolate skulls, which are inscribed with the name of the recipient on the forehead. Sugar skulls can be given as gifts to both the living and the dead.[29] Other holiday foods include pan de muerto, a sweet egg bread made in various shapes from plain rounds to skulls, often decorated with white frosting to look like twisted bones.[23]

Local traditions

The traditions and activities that take place in celebration of the Day of the Dead are not universal, often varying from town to town. For example, in the town of Pátzcuaro on the Lago de Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, the tradition is very different if the deceased is a child rather than an adult. On November 1 of the year after a child's death, the godparents set a table in the parents' home with sweets, fruits, pan de muerto, a cross, a rosary (used to ask the Virgin Mary to pray for them) and candles. This is meant to celebrate the child's life, in respect and appreciation for the parents. There is also dancing with colorful costumes, often with skull-shaped masks and devil masks in the plaza or garden of the town. At midnight on November 2, the people light candles and ride winged boats called mariposas (butterflies) to Janitzio, an island in the middle of the lake where there is a cemetery, to honor and celebrate the lives of the dead there.

In contrast, the town of Ocotepec, north of Cuernavaca in the State of Morelos, opens its doors to visitors in exchange for veladoras (small wax candles) to show respect for the recently deceased. In return the visitors receive tamales and atole. This is done only by the owners of the house where someone in the household has died in the previous year. Many people of the surrounding areas arrive early to eat for free and enjoy the elaborate altars set up to receive the visitors.

In some parts of the country (especially the cities, where in recent years other customs have been displaced) children in costumes roam the streets, knocking on people's doors for a calaverita, a small gift of candies or money; they also ask passersby for it. This relatively recent custom is similar to that of Halloween's trick-or-treating in the United States. Another peculiar tradition involving children is La Danza de los Viejitos (the Dance of the Old Men) when boys and young men dressed like grandfathers crouch and jump in an energetic dance.[30]

The celebration has always been family-oriented, and the idea of having a city-wide parade of people wearing hallowe’en-like costumes started only in 2016, the year after Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer invented a Day of the Dead parade in Mexico City for the James Bond film Spectre. The idea of a massive celebration was also popularized in the Disney Pixar movie Coco.

See also

References

- "Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos y Día de (los) Muertos (México) se escriben con mayúscula inicial" [Día de Todos los Santos, Día de los Fieles Difuntos and Día de (los) Muertos (Mexico) are written with initial capital letter] (in Spanish). Fundéu. October 29, 2010. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- "¿«Día de Muertos» o «Día de los Muertos»? El nombre usado en México para denominar a la fiesta tradicional en la que se honra a los muertos es «Día de Muertos», aunque la denominación «Día de los Muertos» también es gramaticalmente correcta" ["Día de Muertos or "Día de los Muertos"? The name used in Mexico to denominate the traditional celebration in which death is honored is "Día de Muertos", although the denomination "Día de los Muertos" is also grammatically correct] (in Spanish). Royal Spanish Academy Official Twitter Account. November 2, 2019. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- Society, National Geographic (October 17, 2012). "Dia de los Muertos". National Geographic Society. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/dia-de-muertos-tradicion-prehispanica-o-invencion-del-siglo-xx

- https://www.opinion.com.bo/content/print/historiadoras-encuentran-diverso-origen-dia-muertos-mexico/20071102215414274661

- https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/cultura/dia-de-muertos-un-invento-cardenista-decia-elsa-malvido

- https://www.intramed.net/contenidover.asp?contenidoid=49889

- "Indigenous festivity dedicated to the dead". UNESCO. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014. Retrieved October 31, 2014.

- "Dia de los Muertos". El Museo del Barrio. Archived from the original on October 27, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- "Austin Days of the Dead". Archived from the original on November 1, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- https://www.opinion.com.bo/content/print/historiadoras-encuentran-diverso-origen-dia-muertos-mexico/20071102215414274661

- "Dia de los Muertos". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on November 2, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- https://www.inah.gob.mx/boletines/1485-origenes-profundamente-catolicos-y-no-prehispanicos-la-fiesta-de-dia-de-muertos-2

- https://www.inah.gob.mx/boletines/1485-origenes-profundamente-catolicos-y-no-prehispanicos-la-fiesta-de-dia-de-muertos-2

- https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/dia-de-muertos-tradicion-prehispanica-o-invencion-del-siglo-xx

- https://www.eluniversal.com.mx/cultura/dia-de-muertos-un-invento-cardenista-decia-elsa-malvido

- https://www.jornada.com.mx/2001/11/01/09an1esp.html

- https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/dia-de-muertos-tradicion-prehispanica-o-invencion-del-siglo-xx

- https://relatosehistorias.mx/nuestras-historias/dia-de-muertos-tradicion-prehispanica-o-invencion-del-siglo-xx

- Palfrey, Dale Hoyt (1995). "The Day of the Dead". Día de los Muertos Index. Access Mexico Connect. Archived from the original on November 30, 2007. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- Salvador, R.J. (2003). John D. Morgan and Pittu Laungani (ed.). Death and Bereavement Around the World: Death and Bereavement in the Americas. Death, Value and Meaning Series, Vol. II. Amityville, New York: Baywood Publishing Company. pp. 75–76. ISBN 978-0-89503-232-4.

- "5 Facts About Día de los Muertos (The Day of the Dead)". Smithsonian Insider. October 30, 2016. Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

- Brandes, Stanley (1997). "Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico's Day of the Dead". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (2): 275. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179316.

- Turim, Gayle (November 2, 2012). "Day of the Dead Sweets and Treats". History Stories. History Channel. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Godoy, Maria. "Sugar Skulls, Tamales And More: Why Is That Food On The Day Of The Dead Altar?". NPR. Archived from the original on October 28, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2017.

- Castella, Krystina (October 2010). "Pan de Muerto Recipe". Epicurious. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved November 2, 2019.

- "Jamaica iced tea". Cooking in Mexico. Archived from the original on November 4, 2011. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- "These wicked Day of the Dead poems don't spare anyone". PBS NewsHour. November 2, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Marchi, Regina M (2009). Day of the Dead in the USA : The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8135-4557-8.

- "Día de los Muertos or Day of the Dead". Archived from the original on August 29, 2018. Retrieved August 29, 2018.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Day of the Dead. |

- Andrade, Mary J. Day of the Dead A Passion for Life – Día de los Muertos Pasión por la Vida. La Oferta Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-9791624-04

- Anguiano, Mariana, et al. Las tradiciones de Día de Muertos en México. Mexico City 1987.

- Brandes, Stanley (1997). "Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico's Day of the Dead". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 39 (2): 270–99. doi:10.1017/S0010417500020624.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). "The Day of the Dead, Halloween, and the Quest for Mexican National Identity". Journal of American Folklore. 111 (442): 359–80. doi:10.2307/541045. JSTOR 541045.

- Brandes, Stanley (1998). "Iconography in Mexico's Day of the Dead". Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 45 (2): 181–218. doi:10.2307/483058. JSTOR 483058.

- Brandes, Stanley (2006). Skulls to the Living, Bread to the Dead. Blackwell Publishing. p. 232. ISBN 978-1-4051-5247-1.

- Cadafalch, Antoni. The Day of the Dead. Korero Books, 2011. ISBN 978-1-907621-01-7

- Carmichael, Elizabeth; Sayer, Chloe. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Great Britain: The Bath Press, 1991. ISBN 0-7141-2503-2

- Conklin, Paul (2001). "Death Takes a Holiday". U.S. Catholic. 66: 38–41.

- Garcia-Rivera, Alex (1997). "Death Takes a Holiday". U.S. Catholic. 62: 50.

- Haley, Shawn D.; Fukuda, Curt. Day of the Dead: When Two Worlds Meet in Oaxaca. Berhahn Books, 2004. ISBN 1-84545-083-3

- Lane, Sarah and Marilyn Turkovich, Días de los Muertos/Days of the Dead. Chicago 1987.

- Lomnitz, Claudio. Death and the Idea of Mexico. Zone Books, 2005. ISBN 1-890951-53-6

- Matos Moctezuma, Eduardo, et al. "Miccahuitl: El culto a la muerte," Special issue of Artes de México 145 (1971)

- Nutini, Hugo G. Todos Santos in Rural Tlaxcala: A Syncretic, Expressive, and Symbolic Analysis of the Cult of the Dead. Princeton 1988.

- Oliver Vega, Beatriz, et al. The Days of the Dead, a Mexican Tradition. Mexico City 1988.

- Roy, Ann (1995). "A Crack Between the Worlds". Commonwealth. 122: 13–16.