Decimus Burton

Decimus Burton FRS FRSA FSA FRIBA (30 September 1800 – 14 December 1881)[1] was one of the foremost English architects and urban designers of the 19th century.[2][3]:72 He was the foremost Victorian architect in the Roman revival, Greek revival, Georgian neoclassical and Regency styles. He was accomplished also in the cottage orné, picturesque and neogothic styles. He was a founding fellow and, later, vice-president of the Royal Institute of British Architects, and architect to the Royal Botanic Society from 1840 and an early member of the Athenaeum Club, London, whose club premises he designed and which the company of father, James Burton, the pre-eminent property developer of Georgian London, built. Modern architectural historians Guy Williams (1990) and Dana Arnold (2004) contend that Burton's contribution to architecture has been underestimated: as a consequence of the misattribution to John Nash of many of his works; of his vituperation by his neo-gothic rival, Augustus Pugin; and of the consequent retention of his archives by his family.

Decimus Burton | |

|---|---|

Decimus Burton by Sir Thomas Lawrence | |

| Born | 30 September 1800 North House, Southampton Terrace, Bloomsbury, London |

| Died | 14 December 1881 (aged 81) |

| Resting place | Kensal Green Cemetery, London |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Tonbridge School |

| Alma mater | |

| Occupation | Architect |

Notable work |

|

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

Burton's projects include Hyde Park, London (including the gate or screen at Hyde Park Corner, Wellington Arch, Cumberland Gate, Stanhope Gate, Grosvenor Gate, and the Prince of Wales's Gate, Knightsbridge); Green Park and St James's Park; Regent's Park, London (including Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Clarence Terrace, Chester Terrace, and the villas of the Inner Circle (which included his own mansion, The Holme, and the original Winfield House); the enclosure of the forecourt of Buckingham Palace, from which he had Nash's Marble Arch facing the Palace moved to its present site; the clubhouse of the Athenaeum Club; Carlton House Terrace; Spring Gardens in St. James's; and the Palm House and the Temperate House at Kew Gardens. Outside London, Burton planned, and designed the architecture of, the seaside towns of St Leonards-on-Sea and Fleetwood, and the spa town Tunbridge Wells. His development of the Calverley Estate, of which only a small proportion survives, that contained elements of the neoclassical, the Old English and the neogothic styles, was highly commended: it has been described as "a landmark in English domestic architecture". For two decades he was engaged on a vast landscaping project to renovate Phoenix Park in Dublin. He was the architect of Dublin Zoo, and of the renewal of the sea-side resort of Queenstown.

Decimus was the tenth child of James Burton. He was taught by his father, Sir John Soane and John Nash.[4][5] Decimus's siblings included James Burton, the Egyptologist, and Henry Burton, the physician, and he was a cousin of the Canadian author, Thomas Chandler Haliburton, and of the British civil servant Lord Haliburton.

Burton was a leading member of London society during the late Georgian and Regency eras. He has been described by Williams as "rich, cool, well-dressed, apparently celibate, the designer and prime member of the Athenaeum, one of London's grandest gentlemens' clubs", and as one who was treated by the aristocracy "more as a friend than as a professional advisor". He had close friendships with Princess Victoria (the future Queen Victoria); the Duchess of Kent; William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire, John Wilson Croker, Sir John Soane, John Nash and Sir Humphry Davy.

Family

Decimus was the tenth child of James Burton, a pre-eminent London property developer (1761–1837), and Elizabeth Westley (12 December 1761 – 14 January 1837), of Loughton, Essex, the daughter of John and Mary Westley.[6][7] His father was born James Haliburton, and shortened his surname to Burton in 1794, between the births of his fourth and fifth children.[6][8][7][5][9] The paternal grandfather was William Haliburton (1731–1785),[6] a London property developer of Scottish descent.[6][9] On his father's side, Decimus's great-great grandparents were Rev. James Haliburton (1681–1756) and Margaret Eliott, daughter of Sir William Eliott, 2nd Baronet and aunt of George Augustus Eliott, 1st Baron Heathfield.[7]

Decimus was descended from John Haliburton (1573–1627),[8] from whom Sir Walter Scott was descended on the maternal side.[5][6][8] Burton was a cousin of the Canadian author and barrister Thomas Chandler Haliburton[10] and of the British civil servant Lord Haliburton,[9][11][12] who was the first native Canadian to be raised to the Peerage of the United Kingdom.[13]

Education and architectural style

Decimus was born at the 'very comfortable and well staffed' North House in the newly built Southampton Terrace, Bloomsbury, London.[14] From 1805,[15] Decimus was raised in his father's mansion, Mabledon House, in Kent.[16][17] Subsequent to the birth of his twelfth child, Jessy, in 1804, Decimus's father James Burton had purchased a site on a hill about one mile to the south of Tonbridge in Kent, where he constructed, to the designs of the architect Joseph T. Parkinson, in 1805,[15] the large country mansion which he named Mabledon House,[17][4] which was described in 1810 by the local authority as 'an elegant imitation of an ancient castellated mansion'.[17] The majority of the stone that James Burton required for Mabledon was quarried from the hill on which it was to be built, but Burton also purchased the stone that had been released by the recent demolition of a nearby mansion, Penhurst Place.[17] Decimus Burton was coincidentally commissioned to expand Mabledon, his childhood home, on several occasions after it had been sold by his father.[18]

Tuition by his father and George Maddox

Decimus first trained with his father and received drawing lessons from George Maddox.[19][20] Decimus's father James was a talented architect, in addition to the foremost contemporaneous property developer. Williams says of James Burton, "[He] was no ordinary builder. He could have put up an imposing and beautifully proportioned building, correct in every constructional detail, from the roughest of sketches tossed patronizingly at him by a 'gentleman architect'",[6] and "James Burton became adept at relieving the monotony of long residential terraces by allowing their central blocks to project slightly from the surfaces to each side, and by bringing forward, too, the houses at each end", and that "the ironwork in a classical style in James Burton's Bloomsbury terraces was, and often still is, particularly fine, though mass produced".[14] Samuel Pepys Cockerell, advisor to the Governors of the Foundling Hospital, a contemporary of James Burton, commended James Burton's architectural excellence:

Without such a man, possessed of very considerable talents, unwearied industry, and a capital of his own, the extraordinary success of the improvement of the Foundling Estate could not have taken place... By his own peculiar resources of mind, he has succeeded in disposing of his buildings and rents, under all disadvantages of war, and of an unjust clamour which has repeatedly been raised against him. Mr Burton was ready to come forward with money and personal assistance to relieve and help forward those builders who were unable to proceed in their contracts; and in some instances he has been obliged to resume the undertaking and complete himself what has been weakly and imperfectly proceeded with....[21]

In 1815, James Burton took Decimus to Hastings, where the two would later design and build St Leonards-on-Sea and, in 1816, Decimus commenced work in James Burton's office.[22] Whilst working for his father, Decimus was present in the design and construction of Regent Street St. James.[23] Simultaneously, Maddox taught Decimus architectural draughtsmanship, including the details of the five orders. After his first year of tuition by his father and Maddox, Decimus submitted to the Royal Academy a design for a bridge, which was commended by the Academy.[23]

Tuition at Royal Academy Schools by John Soane

Burton has been described by Williams as "an exceptionally clever child" who demonstrated a dispassionate lack of emotion characteristic of his family.[24] Decimus left Tonbridge School in 1816 and entered directly the Royal Academy Schools, in 1817.[1][20][25] His contemporaries at the Royal Academy included Sidney Smirke, with whom he would restore Temple Church, London between 1841 and 1843,[26] and William Tite.[25] As a consequence of his father's social position, Burton was able to enter the Schools at an unprecedentedly young age, without having been previously articled to an architect.[1] There he was taught by Sir John Soane, for whom his brother, James, had also worked.[1][20] Soane was an advocate of the Neo-Palladian style, but had repudiated, including to his students, Robert Smirke's new Opera House, which had not been built in proportion: Soane used special diagrams to demonstrate to his students, including Burton, the failings of Smirke's design, as a consequence of which he was ostracized within the Royal Academy and compelled to suspend his lectures.[27] Soane commended, in contradistinction, in 1815, as an archetype of neoclassical excellence, Robert Adam's [Kedleston Hall]: "In this superb structure he [Adam] has united... the taste and magnificence of a Roman villa with all the comforts and conveniences of an English Nobleman's residence".[23]

Tuition by John Nash

Whereas Decimus's father James Burton was vigorously industrious, and had become 'most gratifyingly rich',[14] John Nash's early years in private practice, and his first speculative developments, which failed either to sell or let, were unsuccessful, and his consequent financial shortage was exacerbated by the 'crazily extravagant' wife whom he had married before he had completed his training, until he was declared bankrupt in 1783.[28] To resolve his financial shortage, Nash cultivated the acquaintance of James Burton, who consented to patronize him.[29] James Burton was responsible for the social and financial patronage of the majority of Nash's London designs,[30] in addition to for their construction,[1] and Decimus became acquainted with Nash through his father.[30] Architectural scholar Guy Williams has written, 'John Nash relied on James Burton for moral and financial support in his great enterprises. Decimus had showed precocious talent as a draughtsman and as an exponent of the classical style... John Nash needed the son's aid, as well as the father's'.[30] Subsequent to the Crown Estate's refusal to finance them, James Burton agreed to personally finance the construction projects of John Nash at Regent's Park, which he had already been commissioned to construct.[1] In return, Nash agreed to promote the career of Decimus Burton.[1] Nash was a vehement advocate of the neoclassical revival endorsed by Soane, although he had lost interest in the plain stone edifices typical of the Georgian style, and instead advocated the use of stucco.[22] Decimus Burton entered the office of Nash in 1815,[31] where he worked alongside Augustus Charles Pugin, who detested the neoclassical style.[24] Decimus established his own architectural practice in 1821.[32] In 1821, Nash invited Decimus to design Cornwall Terrace in Regent's Park, and Decimus was also invited by George Bellas Greenough, a close friend of the Prince Regent, Humphry Davy, and Nash, to design Grove House in Regent's Park.[33] Greenough's invitation to Decimus Burton was 'virtually a family affair', for Greenhough had dined frequently with Decimus's parents and Decimus's brothers, including the physician Henry Burton.[34] Greenough and Decimus finalized their designs during numerous meetings at the opera.[34] Decimus's design, when the villa had been completed, was described in The Proceedings of the Royal Society as, 'One of the most elegant and successful adaptations of the Grecian style to purposes of modern domestic architecture to be found in this or any country'.[35] Subsequently, Nash invited Burton to design Clarence Terrace, Regent's Park.[35] Nash was appointed architectural 'overseer' for Decimus's Regent's Park projects:[36] Cornwall Terrace, York Terrace, Chester Terrace, Clarence Terrace, the villas along the Inner Circle, including The Holme and the London Colosseum attraction, to Thomas Hornor's specifications.[37][1] However, to Nash's great annoyance, Decimus disregarded the latter's advice and developed the terraces according to his own style. As a result, Nash sought, unsuccessfully, to demolish and completely rebuild Chester Terrace.[19][1][4] Decimus subsequently eclipsed his master and emerged as the dominant force in the design of Carlton House Terrace,[1] where he exclusively designed No. 3 and No.4.[38] Decimus also designed some of the villas of the Inner Circle: his villa for the Marquess of Hertford has been described as, 'decorated simplicity, such as the hand of taste, aided by the purse of wealth can alone execute'.[39]

Other influences

Decimus was a polymath and a philomath and extremely erudite in both arts and sciences, as was demonstrated by the diversity of his library – a part of which was auctioned off by his nieces after his death. The sale catalogue listed 347 separate lots, some of which ran into many volumes.[1] The collection bore witness to the range of his intellectual interests. It contained the Proceedings of the Camden Society complete in 135 volumes and transactions of many of the learned societies of which Burton was a member, as well as a complete set of the Histoire Naturelle (70 vols.) of G. L. L. Buffon and Bernard Germain de Lacépède.[1] The architectural texts comprised mostly standard works on classical architecture, such as the five volumes of Colen Campbell, Vitruvius Britannicus by John Woolfe and James Gandon, James Gibbs's Book of Architecture, and William Kent's The Designs of Inigo Jones.[1] Alongside these, there were numerous topographical views and surveys of cities and counties in the collection.[1] There were also some foreign-language texts, including volumes by Charles Percier and Jean-Baptiste Rondelet, a complete set of Giovanni Battista Piranesi's works, and several dictionaries.[1] The absence of an educative Grand Tour early in his career meant that his books and casts were the sources for his early designs, which are technically formal and academic in style.[1][19] However, later on he did travel extensively in Europe and North America.[40] His first tours were of France and Spain, in 1826. He toured Holland in 1846 and Germany in 1850.[1][20] He toured Italy, including Venice.[40] He toured Canada and the United States, after departing Liverpool for Halifax, Nova Scotia, with his cousin Thomas Chandler Haliburton, a Tory MP and author.[40] Burton collected an extensive collection of casts, which informed his work, over 200 of which he donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum, which displayed 18 of the same in its British Galleries.[40] Amongst Burton's possession on his death were an oil painting of St. John, copied by Sir Joshua Reynolds from a work by Raphael; a model of the Temple on the Ilissus at Athens; a statuette of an Angel copied from an original by Thorwaldsen; framed drawings of 'A Royal Palace' by Joseph Gandy ARA (b. 1771), who had been described as 'an English Piranesi'; and a bronze lamp suspended from a snake's mouth.[41] Although he was the leading exponent of Greek revival architecture, Burton was uniquely and significantly influenced by Ancient Roman architecture.[1] It was in his Georgian neoclassical work that he attained the acme of his excellence.[1] Dana Arnold (2002) described his Neoclassical work thus:

"His use of the orders is always correct, but he showed a lack of pedantry in their application that sets him apart from some of his more doctrinaire contemporaries, such as Hamilton and Smirke. From Nash he had learned to combine the classical and the picturesque, and it is the picturesque that is predominant in much of his later work".[20]

In his later career, Decimus designed buildings in the Gothic revival style, the old English style and in the cottage orné style.[1][19] His Gothic revival designs are unoriginal as he had little sympathy for the style.[20]

Life

Burton has been described, by architectural scholar Guy Williams, as "rich, cool, well-dressed, apparently celibate, the designer and prime member of the Athenaeum, one of London's grandest gentlemens' clubs"[42] where Burton "mixed with many of the greatest in the land, meeting the most creative as well as those with enormous hereditary wealth".[43] By 1826, the name of Decimus Burton "was on the lips of everyone who cared at all about the arts and architecture": he was "very well liked [and] his modesty, politeness, and upright bearing were endearing" and "his integrity and professional competence were worthy of the greatest respect".[44] Burton was treated by the aristocracy 'more as a friend than as a professional advisor'[45] and his close friendships with, and patronage by, the aristocracy were undamaged by the vituperation of both his person and his neoclassical architecture by Augustus Pugin and his disciples.[45] The Proceedings of the Royal Society commended Burton's "extreme amiability of character".[45]

The Burtons' social circle included Princess Victoria;[43] the Duchess of Kent;[43] William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire;[46] John Wilson Croker; John Nash;[34] Sir Humphry Davy;[34] George Bellas Greenough;[34] Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood; and their Canadian cousin, Thomas Chandler Haliburton.[10] Decimus and his siblings, Jane, James (born 1786), Septimus, the solicitor, Octavia, and Jessy, would host Thomas on his visits to London.[4][20][3]:72[3]:72[47][48]

Burton was "on excellent terms" with Princess Victoria,[43] and with the Duchess of Kent.[43] The Princess and the Duchess, with several courtiers, had laid the foundation stone of a Decimus Burton School in Tunbridge Wells,[43] and, five weeks later, in autumn 1834, they had stayed, by Burton's invitation, at James Burton's private villa at St Leonards-on-Sea, until several weeks into 1835.[49]

From 1818, Burton resided, with his father, at The Holme, Regent's Park, which has been described as "one of the most desirable private homes in London",[50] which was designed as the Burton family mansion by Decimus, and built by James Burton's own company.[4] The Holme was the second villa to be built in Regent's Park, and the first of those to be designed or constructed by the Burton family.[51] The hallmark of the Burton design is the large semi-circular bay that divided the principal elevation, and which extended for two storeys.[51] The original villa also had a conservatory of polygonal form, which used wrought iron glazing bars, then only recently patented, instead of the then customary wooden bars.[51] The first villa to be constructed in the park was St. John's Lodge by John Raffield.[51]

Burton bought from the Crown a plot at Spring Gardens, St. James's Park, at the east end of The Mall, where he constructed, in the Georgian neoclassical townhouse style, No. 10, 12, and 14 Spring Gardens, as both his townhouse and his principal office.[52][53] The buildings no longer exist, but elevations of them appear in the former LCC's Survey of London Vol. XX, and views of their interiors have been preserved in Hastings Museum.[53] At the end of 1834, Burton had two "comfortable well-staffed homes", one in Spring Gardens and one at Tunbridge Wells,[43] where he had another office at No. 10 Calverley Parade, where the Tunbridge Wells Civic Centre now stands.[53] Williams records that, for Burton, "Money was rolling in. Income tax was of no concern. [Decimus] had a brother who could look after his business affairs and see to his investments".[43]

Burton retired in 1869,[54][55] and subsequently resided at his homes at Gloucester Gardens, Kensington, and St. Leonards Lodge, St. Leonards-on-Sea, which adjoined 'The Uplands' and 'The Lawn' developments which he had designed.[41] He never married nor had issue.[41] He died in December 1881, at 1 Gloucester Road, Kensington, and was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery, alongside his brother Henry Burton, and his sister Jessy Burton.[56][41] Decimus was the last of his siblings to die.[56][57] Over his grave is a tapering sarcophagus of grey Cornish granite, on a stepped base, with a shallow pyramidal cover.[57] His tomb was Grade II listed building in 2001.[57] On his death, his property, including his extensive library and all of his architectural drafts and notes passed to surviving members of his family, mostly to his nephew Alfred Henry Burton (d.1917)[58] or his two unmarried nieces, Helen and Emily Jane Wood, who subsequently sold their share, despite that he had left his library to the Royal Institute of British Architects, of which he had served as President.[1] However, Burton donated 200 of his extensive collection of casts, which informed his work, to the Victoria and Albert Museum, which displayed 18 of the same in its British Galleries.[40] Amongst Burton's possession on his death were an oil painting of St. John, copied by Sir Joshua Reynolds from a work by Raphael; a model of the Temple on the Ilissus at Athens; a statuette of an Angel copied from an original by Thorwaldsen; framed drawings of 'A Royal Palace' by Joseph Gandy ARA (b. 1771), who had been described as 'an English Piranesi'; and a bronze lamp suspended from a snake's mouth.[41] An obituary notice said "No architect was better known, and none was better respected, for he was amiable, considerable, and gentle to all".[59]

Career

Central London Parks

During the second half of the 1820s, the Commissioners of Woods and Forests and the King resolved that Hyde Park, and the area around it, must be renovated to the extent of the splendor of rival European capital cities, and that the essence of the new arrangement would be a triumphal approach to Buckingham Palace, which had been recently completed.[60] The committee of the project, led by the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool, and advised by Charles Arbuthnot, President of the Board of Commissioners of Woods and Forests, selected Decimus Burton as the project's architect: in 1828, when giving evidence to a Parliamentary select committee on the Government's spending on public works, Arbuthnot explained that he had nominated Burton 'having seen in the Regent's Park, and elsewhere, works which pleased my eye, from their architectural beauty and correctness'.[60] Burton intended to create an urban space dedicated to the celebration of the House of Hanover, national pride, and the nation's heroes.[1]

The renovation of Hyde Park, Green Park, and St James's Park, began, in 1825, with the demarcation of new drives and pathways, subsequent to which Burton designed new lodges and gates, viz. Cumberland Gate, Stanhope Gate, Grosvenor Gate, the Hyde Park Gate/Screen at Hyde Park Corner, and, later, the Prince of Wales's Gate, Knightsbridge, in the classical style.[61] There were no authoritative precedents for such buildings, which required windows and chimney stacks, in the classical style, and, in the words of Guy Williams, 'Burton's reticent treatment of the supernumerary features' and of the cast iron gates and railings, was 'greatly admired'.[61]

At Hyde Park Corner, the King required that 'some great ceremonial outwork that would be worthy of the new palace that lay to its rear',[62] and accepted Burton's consequent proposal for a sequence comprising a gateway and a classical screen, and a triumphal arch, which would enable those approaching Buckingham Palace from the north to ride or drive first through the screen and then through the arch, before turning left to descend Constitution Hill and enter the forecourt of Buckingham Palace through Nash's Marble Arch.[62] The screen became the Roman revival Hyde Park Gate/Screen at Hyde Park Corner, which delighted the King and his Committee, and which architectural historian Guy Williams describes as 'one of the most pleasing architectural works that have survived from the neo-classical age'.[62] The triumphal arch became the Wellington Arch at Constitution Hill into Green Park, London, which has been described as 'one of London's best loved landmarks'.[30] Burton designed the arch's iron gates, which were constructed by Bramah and Co. of Pimlico.[63] Burton's original design for the triumphal arch, which was modelled on the Arch of Titus at Rome, on which the central and side blocks of the Screen had been modelled, was more technically perfect, and coherent with the Screen, than that of the arch that was subsequently built: this original design, however, was rejected by the Committee – who had envisaged a design based on the Arch of Constantine (on which Nash's Marble Arch had been modelled) – because it was not sufficiently ostentatious.[44] Burton created a new design, 'to pander to the majestic ego',[44] which was much larger and modelled on a fragment found in the Ancient Roman forum, which was accepted on 14 January 1826, and subsequently built as the present Wellington Arch.[44]

Sculpture of the Triumphal Arch

The arch at Constitution Hill was left devoid of decorative sculpture as a result of the moratorium in 1828 on public building work, and, instead, despite the absolute objection of Burton, was mounted with an ungainly equestrian statue of the Duke of Wellington by Matthew Cotes Wyatt, the son of the then recently deceased James Wyatt, who had been selected by statue's commissioner, and one of its few subsequent advocates, Sir Frederick Trench.[64] Matthew Cotes Wyatt was not competent: Guy Williams contends that he was 'not noticeably talented', and the Dictionary of National Biography that 'thanks to royal and other influential patronage, Wyatt enjoyed a reputation and practice to which his mediocre abilities hardly entitled him'.[64] Trench, and his patrons the Duke and Duchess of Rutland, had told the public subscribers to the statue that the statue would be place on top of Burton's triumphal arch at Hyde Park Corner: Burton expressed his opposition to this proposal 'as plainly and as vehemently as his nature allowed' consistently over successive years, because the ungainly statue would 'disfigure' his arch, for which it was much too large, and the surrounding neighbourhood, because it would have to be placed, contrary to all classical precedent, across, instead of parallel with, the roadway under the arch.[64] Burton had envisaged that his arch would be topped with only a small quadriga whose horses would have been parallel with the road under the arch.[64] Burton's objections were extensively endorsed by most of the aristocratic residents of London.[64] A writer in The Builder asked Lord Canning, the First Commissioner for Woods and Forests, to ban the project: "We have learnt, and can state positively, that Mr. Burton has the strongest objection possible against placing the group in question on the archway... and that he is taking no part whatever in the alteration proposed to be made in the upper part of the structure to prepare it to receive the pedestal... Mr. Burton, through the mildness which characterizes him, has not expressed this opinion so loudly and so publicly as he ought to have done.... an opinion prevails very generally, that he is a party to the proceedings, and this has induced many to be silent who would otherwise have spoken...".[64] The Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, contended that another site would be preferable, and proposed, on behalf of the Crown, to offer any other site, but the statue's subscribers rejected all alternative proposals.[64] Every single MP except Sir Frederick Trench wanted the statue to be placed elsewhere.[64] Canning wrote that 'the remonstrances which reach Her Majesty's Government against the proposed appropriation of the arch are so many and so strong, the representations of its architect, Mr. Burton, in the same sense, are so earnest, and the opinion of every other eminent architect, artist, or other competent authority who has been consulted on the subject is so decided [against the placing of the Wellington statue on the arch]".[64]

Decimus Burton himself wrote, "The arch would, I consider, suffer greatly in importance if the colossal statue in question be placed there, because it would become a mere pedestal. The want of proportion in the proposed surmount, compared with the columns and other details of the architecture, would show that they had been designed by different hands, and without reference for each other. ...I have desired to witness the completion of this building, as originally designed by me, and as approved by the Lords of the Treasury, yet I would prefer that the building should remain for the present in its forlorn and bare state, rather than a colossal equestrian statue should be placed upon it... I fear that if this appropriation of the building should be decided upon, a proposition would soon be made for removing altogether the facades of columns, the slender proportions of which would appear so incongruous and out of proportion compared with the prodigious dimensions of the statue".[64] Burton had realized that the disciples of Pugin and advocates of Pugin's anti-classicism would remove all classical elements from his arch if permitted the opportunity to do so.[64]

The Government placed the Wellington statue on the arch in autumn 1846: Williams contends that the product was 'ridiculous'.[64] The Builder contended, down, unquestionably, it must come. As the network of timber is removed, spar by spar, from before it, so do the folly of the experiment, the absurdity of the conjunction, and the greatness of the sacrifice become apparent. Its effect is even worse than we anticipated – the destruction of the arch by the statue, and of the statue by its elevation on the arch, more complete. Every post brings us letters urging renewed efforts to remove te figure to another site. The contestation about the prospective removal of the statue became national.[64] However, the Government failed to remove the statue, despite that they had professed, when it had been placed, that they would do so if it provoked the aversion which it had provoked.[64] Foreign intellectuals who visited London identified the incongruous fusion of the statue and the arch as 'spectacular confirmation' of the 'artistic ignorance of the English'.[64] Architectural historian Guy Williams writes that "[the] arch at Hyde Park Corner is a visible reminder of one of the fiercest attacks that have ever been launched in the worlds of art and architecture. The face of London might have been very different now – freer, perhaps, of the 'monstrous carbuncles' so disliked by the present Prince of Wales – if the attacked party [Decimus Burton] had been a little more pugnacious, and so better equipped to stand his ground".[30]

In 1847 the problem of accommodating Queen Victoria's expanding family was becoming acute. It was "solved" in two steps by Decimus Burton and W.A. Nesfield. With his eye for landscape, Burton had John Nash's triumphal monument, originally intended as the entrance to the palace, relocated to the north eastern corner of Hyde Park. He consulted on filling in the Buckingham Palace forecourt, creating new interiors and the palace Facade we know today. The Royal Family were able to move in to more spacious premises. Moving the arch, stone by stone, was left to the engineering skills of Thomas Cubitt and took four years. The siting at the Cumberland Gate entrance to the park was eventually completed in 1851.[65]

During 1882, traffic congestion at Hyde Park Corner motivated advocacy for Burton's triumphal arch to be moved to the top of Constitution Hill to create space for traffic.[66] In response to this advocacy, Burton's great-nephew Francis Fearon compiled and published a pamphlet that advocated the removal of the Wellington statue from the arch in the event of the removal of the arch to another location: Fearon contended that the arch should be 'relieved once and for all of its unsightly load'.[66] The campaign led by Fearon was successful: Wyatt's incongruous statue was removed to Aldershot, and its place on Burton's arch, which was moved to Constitution Hill in 1883,[1] was occupied by a Quadriga by Captain Adrian Jones. Jones' statue is not nearly as elegant as Burton's designed statue intended for the arch, but it is more coherent with the arch than Wyatt's statue, and its figures, unlike those of Wyatt's statue, are aligned with the roadway under the arch.[66]

London Zoo

By the end of 1829, Burton had completed London Zoo, which had opened in April 1828,[67] to fervent commendation.[68] Guy Williams records, "From all sides, Decimus Burton's Zoo buildings received the highest praise. They were playful - witty, even - while being architecturally beyond reproach. They made a visit to the Zoo an aesthetic, as well as an educational, pleasure. They brought a suggestion of foreign lands to the flattish expanses at the foot of Primrose Hill".[68] Burton laid out the Zoo in the picturesque style, and designed the early animal houses in the cottage orné style.[67] As a consequence of the success of his London Zoo designs, Burton received more commissions than he were able to complete himself, and, consequently, employed assistants, began to train pupils, and bought a plot at Spring Gardens, St. James's Park, at the east end of The Mall, where he constructed No. 10, 11, and 12 Spring Gardens as both his townhouse and his own office.[52]

Architecture as environment

Burton was one of the first architects to consider the implications of architecture on the creation of distinct urban environments.[1] The evidence given by Burton to two Parliamentary select committees demonstrates the breadth of his knowledge, and the esteem in which his opinion was held by his contemporaries.[1] Burton's evidence to the 1840 Select Committee, which discussed plans to develop Trafalgar Square, popularised his views on urban development.[1][lower-alpha 1] This is one of the first examples of public discourse about an urban space that acknowledged the potential for its national and political significance.[1][19]

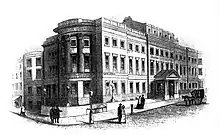

Athenaeum Club

The Athenaeum was founded in 1824 at the instigation of John Wilson Croker, then Secretary to the Admiralty, who was primarily responsible for the organisation and early development of the Club.[70] In 1823, Croker wrote to Sir Humphry Davy, "I will take the opportunity of repeating the proposition I have made to you about a Club for Literary and Scientific men and followers of the Fine Arts. The fashionable and Military Clubs... have spoiled all the Coffee Houses and Taverns so that the artist, or mere literary man... are in a much worse position".[70] Croker suggested 30 names for the Club's organizing Committee, including the Earl of Aberdeen, the Earl of Ashburnham, Earl Spencer, Lord Palmerston, Sir Thomas Lawrence, Francis Chantrey, and Robert Smirke the Younger: all of those invited, except Richard Payne Knight, accepted.[70] The first meeting of the Athenaeum, with 14 men present, was held at the rooms of the Royal Society on 16 February 1824, where a committee was formed that resolved: first, that temporary premises would be rented at 12 Waterloo Place, which had been constructed by the company of Club member James Burton, the pre-eminent London property developer; and, second, that Decimus Burton, then 24 years old, would be commissioned to design a permanent clubhouse.[70] The Trustees of the Club who employed Burton were the Earl of Aberdeen, former Prime Minister and President of the Society of Antiquaries; Sir Thomas Lawrence, President of the Royal Academy; and Sir Humphry Davy, President of the Royal Society.[71] Decimus continued to work for the Club until 1864,[71] and designed Croker's villa at Stokes Bay, near Gosport, in around 1840.[71] Burton's Athenaeum clubhouse is in the Neoclassical style, with both Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, and Renaissance Italian elements:[72] it has a Doric portico with paired columns, and has been described by architectural scholar Guy Williams as 'a building of remarkable grace and astonishing novelty' with a central staircase that is 'distinctly Egyptian in flavour'.[73] The Corinthian-columns of the entrance hall, informed by those of the Athenian Tower of the Winds, are Greek: the barrel-vaulted ceiling Roman.[72] John Summerson contends design were informed by that of Peruzzi's 17th century Palazzo Pietro Massimi in Rome.[72] Burton made himself responsible for the design of as many of the decorative features of the Club as possible, including the clock-cases and the pendant light-fittings.[73] When the Clubhouse was completed in April 1830, the members of the Club Committee stated, "[They] are bound to express their entire satisfaction at the manner in which the work has been carried out by Mr. Burton. They can testify, and indeed the foregoing Accounts evince, the general accuracy of his estimates and they trust that the Club at large, as well as the public, must be satisfied of his professional skill, and the beauty of his architectural designs".[73] Decimus Burton subsequently became the 'prime member of the Athenaeum, one of London's grandest gentlemens' clubs',[42] of which his father James was also a member.[2] The cast of the Apollo Belvedere positioned in the recess at the top of the principal staircase at the Athenaeum was a gift to the Club from Decimus.[74] There is a photographic portrait of Decimus, taken in 1873, preserved at the Club,[75] and the Club retains some furniture designed by Decimus.[2] Another early member was Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood, a close friend of the Burtons.[76]

Calverley Estate

Burton was commissioned to develop the Calverley Estate by John Ward, an MP for whom he had designed his first neoclassical country residence.[77] Great Mount Pleasant, a mansion owned by the Duke of Leeds, had been used by the Princess Victoria and the Duchess of Kent.[77] The villas constructed by Burton on the Calverley Estate were intended for the gentry, and each would be able to accommodate several servants.[77] Burton's design is predominantly Georgian neoclassical in style, but includes elements of the Italianate-,[78] Old English or Tudor-,[78] neogothic-,[78] and cottage orne[79] styles. Burton designed 24 villas, the first of which was completed in autumn 1828: nearly twenty years would pass until the last villa of the series were complete.[77] Burton also constructed a series of Tudor-style servants' cottages, and three grand entrances to the estate: the Victoria Gate, and the less ornate Keston Lodge and Farnborough Lodge.[77] In 1832, Calverley Park Crescent, designed by Burton, modelled partially on those at Bath and Buxton, was constructed at Calverley.[77] The Crescent contained 17 shops, and covered areas for spectators.[77] Burton's development of the Calverley Estate contained elements of the neoclassical-, the Old English-, and the neogothic styles, and was highly commended: it has been described as 'a landmark in English domestic architecture' and the 'prototype garden suburb'.[80] M. Wilson contends that 'Decimus Burton's laying out of the Calverley Estate is the best surviving embodiment of Early Victorian seriousness and refinement'.[81] Christopher Hussey, of Country Life, commended Burton's 'restrained eclectism' in the Calverley developments.[82] Williams contends that the Calverley Estate be 'one of the great architectural successes of the nineteenth century' and that 'Decimus Burton's reputation could be assured by his work here alone',[77] and describes Burton's villas at the estate as 'domestic masterpiece[s]'.[83] Henry Russell Hitchcock described Burton's Calverley Estate as 'the finest extant example' of its kind.[78] Sir John Soane's friend John Britton described Burton's Calverley as a 'beautiful pleasure garden'.[79] Dr. Philip Whitbourn OBE FSA FRIBA contends that Burton has been inaccurately 'sometimes sterotyped as [one] feeling no enthusiasm for the Gothic Revival' and that 'it is as a master not only of the neoclassical but also of the picturesque that Decimus Burton should be remembered'.[79] William Willicombe's subsequent designs on the Calverley Estate, including Lansdowne Road and Calverley Park Gardens, were informed by Burton, with whom he had worked on Burton's earlier parts of the town.[59]

Constructions in the neo-gothic style

Burton was commissioned to design Holy Trinity Church at Tunbridge Wells in the neo-gothic style: he unwisely accepted the commission despite that he was 'neither by temperament nor training' qualified to design a work in this style, of which he knew little, and his design was censured,[84] in addition to commended as a 'beautiful structure' and a 'handsome structure' which 'reflects great credit on the architect'.[85] A more unanimously successful attempt to design in the neogothic style was St Mary's Church, Goring-by-Sea, which he redesigned, for the Tory MP David Lyon, between 1836 and 1838.[86][87]

Neoclassical Houses of Parliament and vituperation by Augustus W. N. Pugin

Burton created a design for a new neoclassical Houses of Parliament.[88] Decimus Burton and his pupils commended the purchase of the Elgin Marbles for the nation, and the erection of a neoclassical gallery in which they could be displayed to the same, and subsequently contended that the destruction of the Houses of Parliament by the fire of 1834 were an opportunity for the creation of a splendid neoclassical replacement of the Houses of Parliament, in which the Elgin Marbles could be displayed: they expressed their aversion that the new seat of the British Empire would ‘be doomed to crouch and wither in the groinings [sic], vaultings, tracery, pointed roof, and flying buttresses of a Gothic building…’:[89] a building of a style that they contended to be improper ‘to the prevailing sentiment of an age so enlightened’.[89] In contradistinction to the neo-gothic style, they commended those who had ‘built St. Paul's Cathedral, to the satisfaction of an applauding posterity, in the more beautiful and universal style of Roman architecture’.[89] However, the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel, wanted, now that he were premier, to disassociate himself from the controversial John Wilson Croker, who was a founding member of the Athenaeum, close associate of the Burtons, an advocate of neoclassicism, and repudiator of the neo-gothic style:[89] consequently, Peel appointed a committee chaired by Edward Cust, a detestor of the style of Nash and William Wilkins, which resolved that the new Houses of Parliament would have to be in either the ‘gothic’ or the ‘Elizabethan’ style.[89] Augustus W. N. Pugin, the foremost expert on the Gothic, had to submit each of his designs through, and thus in the name of, other architects, Gillespie-Graham and Charles Barry, because he had recently openly and fervently converted to Roman Catholicism, as a consequence of which any design submitted in his own name would certainly have been automatically rejected;[89] the design he submitted for improvements to Balliol College, Oxford, in 1843 were rejected for this reason.[90] The design for Parliament that Pugin submitted through Barry won the competition.[89] Subsequent to the announcement of the design ascribed to Barry, William Richard Hamilton, who had been secretary to Elgin during the acquisition and transportation of the Elgin Marbles,[91] published a pamphlet in which he censured the fact that ‘gothic barbarism’ had been preferred to the masterful designs of Ancient Greece and Rome:[89] but the judgement was not altered, and was ratified by the Commons and the Lords.[89] The commissioners subsequently appointed Pugin to assist in the construction of the interior of the new Palace, to the design of which Pugin himself had been the foremost determiner.[89] The first stone of the new Pugin-Barry design was laid on 27 April 1840.[92]

Vituperation of Burton by Pugin

During the competition for the design of the new Houses of Parliament, Burton, "the land's leading classicist",[93] was vituperated with continuous invective, which Guy Williams has described as an "anti-Burton campaign",[94] by the foremost advocate of the neo-gothic style, Augustus Pugin,[95] who was made enviously reproachful that Burton "had done much more that Pugin's father (Augustus Charles Pugin) to alter the appearance of London".[96] Pugin attempted to popularize advocacy of the neo-gothic, and repudiation of the neoclassical, by composing and illustrating books that contended the supremacy of the former and the degeneracy of the latter, which were published from 1835.[97] In 1845, Pugin, in his Contrasts: or a Parallel Between the Noble Edifices of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries and Similar Buildings of the Present Day, which the author had to publish himself as a consequence of the extent of the defamation of society architects therein, satirized John Nash as "Mr Wash, Plasterer, who jobs out Day Work on Moderate Terms", and Burton as "Talent of No Consequence, Premium Required", and included satirical sketches of Nash's Buckingham Palace and Burton's triumphal arch at Hyde Park.[97] Consequently, the amount of commissions received by Burton declined,[98] although he retained a close friendship with the aristocrats amongst his patrons, who continued to commission him.[45] Burton completed a new portico, hall, and staircase for the William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire's residence near Piccadilly;[98] additions to 10 Belgrave Square for the 2nd Earl of Burlington (later the 7th Duke of Devonshire);[99] the enlargement of Grimston Park, Yorkshire, for John Hobart Caradoc, 2nd Baron Howden and the Russian Princess Bagration; additions to Syon House for Lord Prudhoe (later the 4th Duke of Northumberland); and a new town, Fleetwood, in Lancashire, for Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood.[98]

Glasshouses

Decimus was primarily responsible for the 'Great Stove' [conservatory] at Chatsworth for the 6th Duke of Devonshire,[100] for which Joseph Paxton has been erroneously attributed primary responsibility and credit.[100] Architectural historian Guy Williams is unequivocal: Decimus Burton was '[the] designer of the Great Stove at Chatsworth'.[101] Burton, who was advisor to the Royal Botanical Society, also designed the 'Winter Garden' glasshouse of the Royal Botanic Society in Regent's Park, and the Palm House, originally named 'the Stove', and Temperate House at Kew Gardens.[102] The constructed Palm House is the consequence of the collaboration of Burton and Richard Turner: 'Decimus Burton contributed his considerable flair for creating refined and elegant structures and Richard Turner a singular talent for metal fabrication'.[103] Burton's Palm House has been described as 'one of the boldest pieces of 19th century functionalism in existence - much bolder indeed, and hence aesthetically much more satisfying than Crystal Palace ever was'.[104] Dr. Philip Whitbourn OBE FSA FRIBA contends that Burton's Palm House 'could have a just claim as the world's most important surviving Victorian glass and iron structure'.[104] Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace was derived almost entirely from the glasshouse work of Decimus Burton and Richard Turner.[105] Subsequent to his retirement there, Decimus designed and constructed several buildings at St Leonards-on-Sea.[10] Burton's Temperate House at Kew, which is double the size of his Palm House and the world's largest surviving Victorian glass structure,[106] was only completed after his death, in 1898, and has become one of his most popularly acclaimed works:[94] Williams writes of the Temperate House, "It makes one wonder how much the appearance of London might not have been improved if Augustus W. N. Pugin had never started his anti-Burton campaign".[94] Burton's other works at Kew include the Museum No.1, the Campanile, and the Main Entrance Gates to Kew Green.[106] Burton's Glasshouses at Kew constituted the UK's case for Kew to be made an UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2002.[106][107]

Further studies and elections

From 1830 to 1834, Burton studied at Clifford's Inn. The architectural historian, Sir Nikolaus Pevsner, believes that Decimus was the designer of the Gatehouse and the Inn buildings.[108]

In 1832 Decimus Burton was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society.[7] He became a Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts; a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London; a founding Fellow, and later Vice-President, of the Royal Institute of British Architects;[53] and was architect to the Royal Botanic Society from 1840.[19][1][109][110][37] An 1828 testimonial for his election to Fellowship of the Society of Antiquaries described him as 'Architect and Gentleman, well versed in the History and Antiquaries of this Kingdom':[91] he was elected FSA on 8 January 1829, during the tenure of W. R. Hamilton, Chief Commissioner of Woods and Forests, as Vice-President.[91]

Decimus was an early member of the Athenaeum Club, London, whose mansion he designed and his father, James Burton, built. James was also an early member of the Club.[2][111] The cast of the Apollo Belvedere positioned in the recess at the top of the principal staircase at the Athenaeum was a gift to the Club from Burton.[112] There is a photographic portrait of Decimus Burton, taken in 1873, preserved at the Club, which retains some furniture designed by him.[2] Burton had over 30 years of correspondence with John Wilson Croker, a co-founder of the Club, and was a close friend of Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood, who was another early member.[20][47] [111]

Protégés

Burton trained his nephew, Henry Marley Burton FRIBA (1821–1880)[94] the son of his eldest brother, William Ford Burton.[41] Henry Marley Burton succeeded to Decimus's architectural practice subsequent to Decimus's retirement.[94][20][41] In 1866, Henry Marley was commissioned by John George Dodson, 1st Baron Monk Bretton to design a mansion at Coneyborough. Decimus had previously designed Bineham in Chailey for Dodson's brother-in-law, John George Blencowe. Burton also taught the architects Henry Currey FRIBA,[113][114] George Mair,[114] John Crake,[114] Arthur William Hakewill,[114] and Edward John May FRIBA,[114][56] who was his last pupil.[115][116][37]

Legacy

Despite the fact that he had left his library to the Royal Institute of British Architects, of which he had served as President, most of it was deposited instead with his two unmarried nieces, Helen and Emily Jane Wood, who subsequently sold it, and the remainder was distributed among other family members. As a consequence, according to Dana Arnold, there is a gross imbalance between the ‘scale and significance’ of Decimus Burton's work and the amount of documentary evidence about it that has come into the public domain. Given the fragmentary nature of written sources concerning his work, he has tended to be relegated, quite undeservedly, 'to the margins of architectural histories’. However, Burton's works in London, especially those around Hyde Park, Green Park, Regent's Park, remains a lasting and resplendent memorial.[1] His reputation has increased since the commencement of the 20th century,[117] during which a Burtons' St Leonards Society has been founded in St Leonards-on-Sea to 'encourage the preservation of the work of James and Decimus Burton and to prevent development unsympathetic to its character', which has successfully thwarted several attempts to create new developments that would have violated the beauty of the Burtons' project.[117] Architectural historian Guy Williams writes that "[the] arch at Hyde Park Corner is a visible reminder of one of the fiercest attacks [on Decimus Burton and neoclassicism, by Augustus Pugin] that have ever been launched in the worlds of art and architecture. The face of London might have been very different now – freer, perhaps, of the 'monstrous carbuncles' so disliked by the present Prince of Wales – if the attacked party [Decimus Burton] had been a little more pugnacious, and so better equipped to stand his ground".[30]

The recently completed restoration (2018) of the Temperate House at London's Kew Gardens has prompted a re-evaluation of Burton's horticultural designs.[118] Douglas Murphy contends that Burton's use of "Iron and glass, through shedding ornament and aiming for efficient performance over capricious pomp, was retroactively understood as the historic forerunner of Modernism, meaning that what had been thought of as mere engineering was allowed to enter the pantheon of true architecture. Burton's name was now fortunately attached to some of the most significant works of that type".[119]

Burton's legacy on either side of the Irish Sea endures. In April 2017 the Hearsum Collection, in collaboration with The Royal Parks and Ireland's Office of Public Works, mounted an exhibition at Dublin's Phoenix Park entitled Parks, Our Shared Heritage: The Phoenix Park, Dublin & The Royal Parks, London, demonstrating the historical links between Richmond Park (and other Royal Parks in London) and Phoenix Park.[120] This exhibition was also displayed at the Mall Galleries in London in July and August 2017.[121]

List of architectural projects

The projects are listed by county in alphabetical order. The list is based on the work of Whitbourn 2003, and on the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry for "Burton, Decimus (1800–1881)", by Dana Arnold. Any other sources are specified individually.

Buckinghamshire

- Stockgrove House, Buckinghamshire/Bedfordshire border (1831) demolished circa 1928

Derbyshire

- The Great Conservatory and the Home Farm at Chatsworth (1836–1840: Conservatory demolished circa 1920))[38]

Great Conservatory, Chatsworth House, with Joseph Paxton

Great Conservatory, Chatsworth House, with Joseph Paxton

Dorset

- Lower Pleasure Gardens, Bournemouth (1840s)

- St Mary's church, Bradford Peverell (1850)

East Sussex

- Oaklands Park, Sedlescombe Sedlescombe (1830)

- Adelaide Crescent, Hove, Brighton, (1831 – 1834, for Sir Isaac Goldsmith).[38] The style that Burton used here was the progenitor of that which Osbert Lancaster subsequently termed 'Kensington Italianate'.[113] (Only numbers 1–10 were built in Burton's style: the remainder were completed from 1850 to a much grander design)

- Wick Hall, Hove (1840; demolished 1936)

- Furze Hill Villa, Brighton, (1833, for Sir Isaac Lyon Goldsmith)[38]

- Holy Trinity Church, Eastbourne (1837-9, later extended)

- St. Augustine's Church, Flimwell (1839)

- Worth Park, Sussex, (additions, 1833, for Joseph Montefiore)[38]

St Leonards-on-Sea

In 1828 Burton's father, James, bought an estate in East Sussex, on which he built the new town of St Leonard's-on-Sea, as a pleasure resort for the gentry. Decimus designed the majority of the buildings.[5][122]

North Street with Kenilworth Road in background

North Street with Kenilworth Road in background Steps down to Kings Road

Steps down to Kings Road Warrior Square Station, St Leonard's-on-Sea

Warrior Square Station, St Leonard's-on-Sea

Central London

- The Holme, Inner Circle, Regent's Park (1818). From 1818, Burton resided, with his father, at The Holme, Regent's Park, which has been described as 'one of the most desirable private homes in London',[50] which was designed as the Burton family mansion by Decimus, and built by James Burton's own company.[4] The Holme was the second villa to be built in Regent's Park, and the first of those to be designed or constructed by the Burton family.[51] The hallmark of the Burton design is the large semi-circular bay that divided the principal elevation, and which extended for two storeys.[51] The original villa also had a conservatory of polygonal form, which used wrought iron glazing bars, then only recently patented, instead of the then customary wooden bars.[51] The first villa to be constructed in the park was St. John's Lodge by John Raffield.[51]

- Clarence Terrace, Regent's Park (1823)[37][38]

- The original Winfield House (1825) for the 3rd Marquess of Hertford, which became known as 'St. Dunstan's Villa'.[123] Burton's creation was described as, 'decorated simplicity, such as the hand of taste, aided by the purse of wealth can alone execute'.[39] Burton's creation was subsequently reconstructed as a building with a modern exterior.[123] In 1819, Burton had also designed for the same commissioner a South Villa, the designs of which were exhibited at Royal Academy in 1822 and in 1825, the manuscript drawings of which are now in the Library of the Architectural Association, London.

- Cornwall Terrace, Regent's Park, London (1821)[38]

- Chester Terrace, Regent's Park

- York Terrace, Regent's Park

- Hyde Park Screen (1824)[38]

- Hyde Park, London: Stanhope, Grosvenor, and Cumberland Gates and their lodges.[38] More extensive plans for the Parks that were not realized included the dramatic circular Bayswater Gate and Lodge, and an entrance to Green Park from Piccadilly based on a Greek temple design.[1]

- Parliamentary Mews, Prince's Street, Westminster (1825).[38] Remodelled in 1853 and 1854, also by Decimus Burton, after which they were named 'Stationary Office'.[38]

- Spring Gardens, St. James's Park, No. 10, 12, and 14, all for his own townhouse and office (1827).[38]

- Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner, (1827)[38]

- Athenaeum Club, London Clubhouse (1827–1830)[124][38]

- Royal Naval Club, 160 Bond Street (1828)[38]

- 3 Carlton House Terrace, for Lord de Clifford, (1828)[38]

- 4 Carlton House Terrace, for Lord Stuart de Rothesay, (1828)[38]

- Royal Society of Literature, St. Martin's Place, (1830)[38]

- Charing Cross Hospital (1830)[38]

- Magazine of the Grenadier Guards, Hyde Park, (redesign)(1830)[38]

- Clifford's Inn (1830)[38]

- 80 Pall Mall, (alterations), (1830)[38]

- 6 Whitehall Gardens(1831)[38]

- Holland House, Kensington, (restoration, for 3rd Lord Holland), (1833)[38]

- House of Commons (not built, 1833)[38]

- 10 Belgrave Square (improvements) (1839)[38]

- 18 Hyde Park Gardens (1841)[38]

- Temple Church, London (restoration, with Sidney Smirke) (1841–1843)[38][26]

- Devonshire House, Piccadilly, (additions: portico, hall, staircase),(1843)[38]

- Lodge for the Prince of Wales's Gate, Hyde Park, (1846)[38]

- The Ferns, Victoria Road, Kensington, (1864), (improvements, for E. W. Cooke R. A.), (1864)[38]

- Grove House (subsequently called 'Nuffield Lodge') Regent's Park[38]

- Holford House (1833),

- St. John's Lodge, (for John Mabberley MP) (let in 1829 to the Marquess of Wellesley, who employed Burton to enlarge it.

- London Colosseum, Regent's Park, (1823–1827).[38] It was informed by the design of the Roman Pantheon,[125] but also by Grecian principles, and had a Doric portico.[124] Its dome was larger than that of St. Paul's Cathedral.[124] It was described as 'one of the finest and best proportioned of Greco-Doric in the Metropolis'.[72] It was demolished in 1875.[124]

- Zoological Society of London Gardens (1826–41)

- Botanical Society of London Gardens (1840–59).

- Parliamentary Stables, Westminster

- London Zoo, various buildings (1826–28) and (1831–34); surviving buildings include the Giraffe House, the Camel House, the Raven Cage and the tunnel under the Outer Circle, connecting the two parts of the zoo. He also designed the llama building (1828) with a clock tower.[126]

- The Geological Society's apartments at Somerset House (1828)

- The former United Service Club, Pall Mall, London alterations.

- The original Charing Cross Hospital, London, WC. (1831–39)

- The Oriental Club. The construction of additions to the club building that were designed by Decimus Burton, in 1853, was superintended, when eventually commenced, in 1871, by his nephew, Henry Marley Burton.[127]

- Kew Gardens. Layout of the gardens and paths, the Palm House (1844–48) (at the time the largest greenhouse in the world), Main Gate (1846, renamed The Elizabeth Gate in 2012 to mark the Diamond Jubilee of Elizabeth II), the Water Lily House (1852), The Museum, (1857, extended 1881), The Temperate House, (1859–1863) (the flanking wings, also part of Burton's design, were not built until 1897–98)

- Beulah Spa, Upper Norwood, London SE (1831). Burton landscaped the grounds and designed the buildings for the entrepreneur, John Davidson Smith. It became a popular society venue attracting large crowds to its fêtes.[128] Burton's buildings were in a " rustic" style, with the ticket office in the form of a thatched cottage.[129] The Spa closed in 1856 soon after the opening of the nearby Crystal Palace.[lower-alpha 2] Burton also drew up designs for a grand crescent of terraced houses on hill above the spa, which was, however, never built.[129]

- Holwood House, Keston (1823–1826)[38] This has been described as 'splendidly Grecian... the best thing of its kind in Kent'.[131]

- House at Harrow School for Rev. J. W. Colenso (1838)[38]

- Headmaster's House, Harrow School, (1840, enlarged by Burton in 1845 and 1846)[38]

- Lodges, Gates, at Chiswick House; additions to the Grove; additions to Sutton Court, Chiswick (1835, for 6th Duke of Devonshire)[38]

Inner Circle, Regent's Park, 1833 Schmollinger map

Inner Circle, Regent's Park, 1833 Schmollinger map St. John's Lodge, Regent's Park

St. John's Lodge, Regent's Park

London Zoo c.1854

London Zoo c.1854 Hyde Park and part of Kensington Gardens c.1833

Hyde Park and part of Kensington Gardens c.1833 Screen, Hyde Park Corner

Screen, Hyde Park Corner Aerial view of Hyde Park

Aerial view of Hyde Park Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner

Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner Green Park, London, and Constitution Hill

Green Park, London, and Constitution Hill St James's Park Lake, to the northwest, and Buckingham Palace

St James's Park Lake, to the northwest, and Buckingham Palace Green Park and St. James's Park c.1833

Green Park and St. James's Park c.1833

Charing Cross Hospital, Villiers Street London, c. 1902

Charing Cross Hospital, Villiers Street London, c. 1902.jpg.webp) Elizabeth Gate, Kew Gardens

Elizabeth Gate, Kew Gardens

The Temperate House, Kew Gardens

The Temperate House, Kew Gardens Kew Gardens Water Lily House

Kew Gardens Water Lily House

Hertfordshire

- Haydon Hill House, Bushey (1840s; later extended – now a Grade II listed building and converted into flats)

Kent

- Calverley Estate, Tunbridge Wells, (commenced 1828)[38]

- Holy Trinity Church, (1827–1829) Royal Tunbridge Wells[132]

- Calverley Estate (Calverley House is now a hotel), Tunbridge Wells (1828)

- Calverley Park Crescent, Tunbridge Wells (c.1833)

- Burrswood Hospital, Tunbridge Wells (1830s)

- St. Peter's Church, Southborough, Kent (1830)[132] altered in the 1880s

- Bentham Hill House, Southborough, Kent (1830–3) a small country house in Deveyesque style for Alexandre Pott, now converted into flats.It has been termed DB's most picturesque house.[38]

- St. Mary's Church, Riverhead, Kent (1831)[132]

- Culverden House, Tunbridge Wells, Kent (1830), demolished to make way for the Kent and Sussex Hospital. All that remains of the Burton designed estate is the woodland part of the grounds

- East Cliffe House (additions), Ramsgate, Kent, for Sir Moses Montefiore[38]

.JPG.webp)

Calverley House, c. 1860, Royal Tunbridge Wells

Calverley House, c. 1860, Royal Tunbridge Wells Calverley Park gardens

Calverley Park gardens Calverley Park Crescent Royal Tunbridge Wells

Calverley Park Crescent Royal Tunbridge Wells Tunbridge Wells, Victoria Lodge

Tunbridge Wells, Victoria Lodge St Peter's Church, Southborough, Kent

St Peter's Church, Southborough, Kent Church of St Mary, Riverhead, Kent

Church of St Mary, Riverhead, Kent Great Culverden Park Lake

Great Culverden Park Lake

Lancashire

Burton's work with his father on the East Sussex town of St Leonards-on-Sea, between 1827 and 1837, had so impressed their friend, and fellow Atheneaum Club member, Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood that he commissioned Burton to design and lay out his new port and seaside resort of Fleetwood.[47]

- The Beach Lighthouse, Fleetwood (1839–40)

- St Peter's Church, Fleetwood (1839–41)

- Pharos Lighthouse, Fleetwood (1840)

- North Euston Hotel, Fleetwood (1841–42)

- Queens Terrace GardensQueen's Terrace, Fleetwood

- Fleetwood, Town Hall

- The Customs House, now the Fleetwood Museum

Norfolk

- Sennowe Hall, near Guist, extended 1855–56, remodelled 1908 – very little of Burton's work survives.

Gate and lodges, Sennowe Hall, Norfolk

Gate and lodges, Sennowe Hall, Norfolk

Nottinghamshire

- The Grammar School, Retford (1855–1857)

Burton's King Edward VI Grammar School, Retford

Burton's King Edward VI Grammar School, Retford

West Sussex

- St Mary's Church, Goring-by-Sea (1836–38). Burton was commissioned by David Lyon to redesign the church.[87]

Republic of Ireland

Burton spent two decades of his life modernising and landscaping the neglected site of Phoenix Park, Dublin. This included many works on the paths, relocation of monuments and construction of gates to an area previously dominated by military and police barracks.[133]

- Lay-out and gates, Dublin Zoo, Garda Síochána headquarters in Phoenix Park, Dublin (1840)

- Cobh, Co. Cork, the invitation to make improvements to the sea-side resort in the 1840s was made by George Brodrick, 5th Viscount Midleton

- Martinstown House, Co Kildare (1833)[134][135]

Phoenix Monument, Phoenix Park, Dublin

Phoenix Monument, Phoenix Park, Dublin._Postcard%252C_c._1905.jpg.webp) Dublin - Phoenix Park Jaunting car Postcard, c. 1905

Dublin - Phoenix Park Jaunting car Postcard, c. 1905 Phoenix Park - Wellington Monument

Phoenix Park - Wellington Monument

Dublin Zoo entrance lodge (1833)

Dublin Zoo entrance lodge (1833).jpg.webp) Queenstown, aka Cobh, c. 1890

Queenstown, aka Cobh, c. 1890_dominates_Cork_Harbour_one_of_the_largest_natural_harbours_in_the_world_(7359306822)_(2).jpg.webp) Cobh dominates Cork Harbour

Cobh dominates Cork Harbour

See also

References and notes

- The proceedings were reported in the Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal, 7 September 1840[69]

- One widely publicized event was a "Grand Scottish Fête" on 16 September 1834 "with a tightrope performance by Pablo Fanque, the black circus performer who would later dominate the Victorian circus and achieve immortality in The Beatles song, "Being for the Benefit of Mr. Kite!".[130]

- Arnold, Dana. "Burton, Decimus". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/4125. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Athenaeum Club, London. Homepage".

- Davies, Richard A. (2005). Inventing Sam Slick: A Biography of Thomas Chandler Haliburton. University of Toronto Press. pp. 71–74, 79, 151. ISBN 978-0-8020-5001-4.

- Bowdler, Roger. "Burton [Haliburton], James". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/50182. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Who were the Burtons?". The Burtons' St Leonards Society. Retrieved 18 June 2016.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 18. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- "Pedigree of Decimus Burton (1800–1881), The Weald, Public Archives of Kent, Surrey, and Sussex".

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Davies, Richard A. (2005). Inventing Sam Slick: A Biography of Thomas Chandler Haliburton. University of Toronto Press. pp. 71–73.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 127. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Burton, James (1783–1811). "The Diary of James Burton". The National Archives. Retrieved 18 June 2018 – via Hastings Museum and Art Gallery.

- "Haliburton [Haleburton; formerly Burton], James (1788–1862), Egyptologist".

- Morgan, Henry James, ed. (1903). Types of Canadian Women and of Women who are or have been Connected with Canada. Toronto: Williams Briggs. p. 142.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 135. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 19–20. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- "History of Mabledon House, Kent". Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- Curl, James Stevens (1999). The Dictionary of Architecture. Vol. 1 Aba – Byz. Oxford University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-19-860678-8.

- Arnold, Dana (2003). Reading Architectural History. Routledge. pp. 66–67. ISBN 978-1-134-53231-5.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 20–21. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 28. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 29. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 21. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 45. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 14. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 16. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 11–12. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 30. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 136. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 38. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 38–39. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 40. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Arnold, Dana (2005). Rural Urbanism: London Landscapes in the Early 19th Century. Manchester University Press. p. 58.

- Basic biographical details of Decimus Burton at the Dictionary of Scottish Architects Biographical Database.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 135–157. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Jones, Christopher (2017). Picturesque Urban Planning – Tunbridge Wells and the Suburban Ideal: The Development of the Calverley Estate 1825 – 1855. University of Oxford, Department of Continuing Education. p. 209.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. pp. 12–13. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. Inside Cover. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 66. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 51. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 108. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 84. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Curtis & Curtis 1994.

- Cooke, Neil M. R. "Haliburton [Haleburton; formerly Burton], James (1788–1862), Egyptologist". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/11926. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 66–67. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 133. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 37. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 55. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Basic biographical details of Henry Marley Burton at the Dictionary of Scottish Architects Biographical Database.

- "Fountain Design of Edgar Burton to commemorate James Burton". Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 130. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Historic England. "Tomb of Decimus Burton (1389239)". National Heritage List for England.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 157. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 49. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 49–50. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 50. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 85–94. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Historic England. "Marble Arch (1492760)". PastScape. Retrieved 6 December 2018.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 131–133. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. p. 54. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- "The Nelson Monument and Trafalgar Square". Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. 7 September 1840. p. 304. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 43–45. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. pp. 15–16. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 46–48. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- "Victorian Web: Grand Staircase, The Athenaeum Club".

- Arnold, Dana (2002). Entry for Burton, Decimus; Biographical Dictionary, in Reading Architectural History. Routledge. pp. 66–67.

- Curtis, Bill (1994). The Golden Dream: The Biography of Sir Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood. Life Publications. ISBN 1-68874-371-5.

- Williams, Guy (1990). Augustus Pugin Versus Decimus Burton: A Victorian Architectural Duel. London: Cassell Publishers Ltd. pp. 56–59. ISBN 0-304-31561-3.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. pp. 24–25. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.

- Whitbourn, Philip (2003). Decimus Burton, Esquire: Architect and Gentleman (1800–1881). Royal Tunbridge Wells Civic Society. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-9545343-0-1.