Decreasing graduation completion rates in the United States

The graduation completion rate is the measure reflecting the number of students who complete their graduation and receive a degree from an educational institution. The drop-out rate is the measure reflecting the number of students who disengage with the educational institutions they are enrolled in. Those measures are calculated by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), the primary federal U.S. entity for collecting and analyzing data related to education.

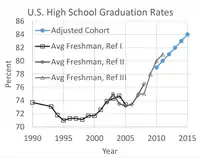

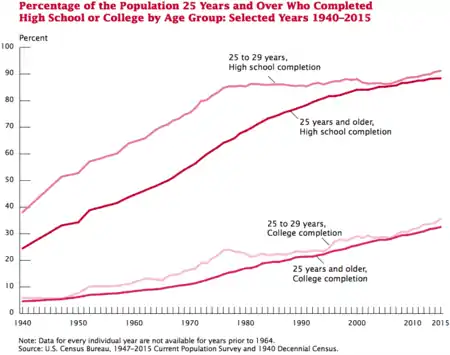

Graduation rate has been reported to be decreasing over the past decades in the U.S.[1] However, the percentage of dropouts among 16- to 24-year-olds has shown some decreases over the past 20 years.[2] The substantial growth in college enrollment among high school graduates has not been matched with a comparable expansion in college degree attainment.[3]

Overview

Historical background

Degree completion has been decreasing since 1970. Bound, Lovenheim and Turner (2010) studied why the college completion rate declined.[3] Their main explanations of the decreasing rate are the changes in student preparation and the collegiate resources. The authors explain that between 1970 and 1999, post-secondary institutions saw a significant increase in enrollments and, at the same time, a decrease in college completion. "Partly as a consequence of the substantial increase in the college wage premium since 1980, a much higher fraction of high school graduates enter college today than they did a quarter century ago. However, the rise in the fraction of high school graduates attending college has not been met by a proportional increase in the fraction who finish."[3]

A study by the Higher Education Research Institute of the University of California underlines that in 1994. fewer college students were completing their college in four years than in 1984. The completion rate within four years was 36.4% in 1994, whereas it was 46.7% in the late 1960s. The degree completion when the students were allowed to graduate in six years was 58.8% in 1994.[4] "The fact that these public-private differences decline somewhat when six-year rates are used suggests that students in the public colleges and universities are taking longer to complete their degrees," says Alexander Astin, co-author of the study and director of the Higher Education Research Institute. The current trend is of longer time spent to graduate than it was 50 years ago.

Main causes

The main causes of the decreasing college completion rate are the lower preparation level of the students and the small allocation of resources dedicated to instruction and institutional choices, according to Bound, Lovenheim and Turner and their study on "Understanding Decrease in Completion Rates and Increase in Time to Degree".[5] The resources allocated to institutions haven't been enough to offset the increase of new students enrollment in higher education institutions.

The abstract of the study "Understanding Decrease in Completion Rates and Increase in Time to Degree" by John Bound, Michael Lovenheim, Sarah Turner (2007) says:

Persistent increases in the wage premium for college graduates in recent decades have not been matched by gains in collegiate attainment. Indeed, the proportion of students entering college who receive degrees has slowed while time to completion of the baccalaureate degree has increased markedly among college graduates in the United States over the last three decades. Using data from the NLS72 and NELS:88 longitudinal surveys, we find that while enrollment rates have increased disproportionately among those students less well prepared for college, these students are unlikely to complete BA degrees resulting in an overall decline in the completion rate. In contrast, we find that changes in the composition of the college going population can account for essentially none of the observed increase in time to degree. The increase in time to degree is localized among those who begin postsecondary education at public colleges outside the most selective universities. We produce evidence that increased stratification in U.S. higher education and reductions in collegiate resources outside the top-tier of institutions are a primary component of the explanation for the observed increases in time to degree, with increases in time to degree relatively concentrated in states that have experienced rapid growth in the size of the college-age population and dilution in resources per student at many public colleges. Further, evidence of increased hours of employment among students is consistent with students working more to meet rising college costs thereby negatively affecting the length of time it takes them to complete college.[5]

Current situation

The US Census Bureau in 2009 reported that, nationally, 9% of 18–24 year-olds and only 27.5% of those 25 years and older had a bachelor's degree or more. Massachusetts is the state where the completion rate is the highest with 37.8% of citizens 25 years and older having a bachelor's degree. In West Virginia, the completion rate is the lowest with only 17.1%[6] of the population having bachelor's degrees.

In his 2010 State of the Union Address, President Obama said that he wants the United States to have the highest proportion of college graduates in the world by 2020. To reach this "big goal", American college graduates should increase by 50%, adding at least 8 million additional graduates. Obama said that increasing college completion rate is important to increase economic opportunities and lower social costs for individuals.[7]

Early colleges

Early colleges have lower drop-outs rate than community colleges and universities. The early college high school programs provide students the opportunity to receive a high school diploma and an associate's degree, or up to two years of credit toward a bachelor's degree, in four years. Students take a mixture of high school and college classes in order to obtain their high school diploma and associate's degree. Each early college high school is a public school and open to any residents in the school district. Early colleges have the advantage of allowing student an alternative to the traditional access to diplomas.

Community colleges

Community colleges have the mission to provide better access to higher education and graduation for under-served populations. Greater access and success in post-secondary education is a primary element for decreasing income inequalities and increasing the productivity of America's workers.[8] In 2008, 46% of all undergraduate students in the US attended community colleges.[9] Long and Kurlaender studied the graduation differences between community colleges and universities and found that community college students were 14.5% less likely to complete their degree within 9 years as opposed to students in universities.[10] Recent research studied the effect of incentive payments at community colleges and found that they increased the likelihood of low-income students enrolling in the second semester after random assignment and total number of credits earned, with program group students completing nearly 40 percent more credits.[11] Other recent research shows other methods of increasing graduation and persistence rates. Century College in Minnesota implemented GPS Lifeplan to help develop goals in areas such as education, leadership, and finance. The concepts in GPS Lifeplan are integrated in many areas of the college such as New Student Seminars and other areas of curriculum. New full-time student using GPS Lifeplan retention rates were 81% compared to overall retention of 72%.[12]

Universities

In universities, efforts are made on targeting the "at-risk" students to avoid drop outs, and creating aligned programs for better coordination between high schools and universities.[13] Successful transfer to 4-year institutions is an issue that concerns every higher educational institution. Academic preparation in high school and solid coordination with those institutions are highly suitable for improving graduation rates.[14]

Public policies

Organizations and associations such as Lumina Foundation for Education and Delta Cost Project study how to reallocate the limited resources in ways that can increase college completion rates. Studies suggest that in order to respond to this issue of low graduation rates, states should focus on long term policy rather than short-term fixes. The re-examination of how resources are allocated would help to improve the higher education system and avoid drop outs. Several studies have been conducted in order to guide policies toward better ways to manage resources and drive expenditures.

Webber and Ehrenberg studied the overall impact and the institutional-level impact based on institutional average SAT scores and the average federal Pell Grant given to students at the institution. They found that an increase in expenditures on instruction and student services resulted in higher education rates. The reallocation of resources from instruction to student services would result in a consequent increase in graduation rates. The researchers underline that the institutions with students academically unprepared or economically disadvantaged invest in focusing more on getting student services to potentially raise their students graduation rates.[15]

On March 22, 2011, Vice-President Joe Biden declared[16] "Right now we've got an education system that works like a funnel when we need it to work like a pipeline... We have to make the same commitment to getting folks across the graduation stage that we did to getting them into the register's office. The dreams and skills of our college graduates will pave the way to a bright economic future for our nation".[17]

A New College Completion Tool Kit[18] has been developed by the federal government to help the governors and state governments develop better strategies for higher-education promotion. The solutions proposed by the College Completion Tool Kit urge government to set up financial incentives to increase completion rate. The federal government advises to base funding formulas on enrollment rate but also on performance measures and outcome indicators. In order to improve institutions of higher education, states and public policies should:

- strengthen high school academic rigor

- make "college prep" the default track in high school

- create opportunities for high school students to earn college credits

- develop and implement aggressive outreach strategies to reengage adult students who have received some college training short of certificate on degree attainment but dropped out

- restructure remedial education to meet individual student needs successfully

- restructure post-secondary education delivery to ensure that students complete their degrees in a timely manner

The case of Louisiana

The Lumina Foundation for Education proposes solutions to increase college completion rates and to meet President Obama's graduation goal.[19] The strategies highlighted by the Lumina Foundation for Education are to increase the rate at which students complete college and to provide ways for adults in the workforce to return to college to complete degrees.[20]:2

In Louisiana, the college attainment rate is 27%.[20]:49 In order to reach the "big goal", Louisiana would need to increase its annual degree production by 8.2%. The Lumina Foundation for Education advises some strategies:

- to target Louisiana residents who have completed some college without earning a degree

- to target parishes and regions in greater needs and to focus the state's effort there

Louisiana's challenge is to increase college students' success for working adults, low income students, first generation students and minority students.[20]:50

Controversy

The graduation completion rate is contested. In January 2010, The Chronicle of Higher Education stated that this rate fails to count students who take a long time to complete their degrees.[22] They qualified the rate as "an incomplete measure of institutional quality. The data describes a minority of all enrolled students, counting only full-time, first-time students who enroll in the fall and complete degrees within "150 percent of normal time"—six years for students seeking bachelor's degrees. The graduation rate excludes students who transfer to other colleges and earn degrees there. It also excludes transfer students who come in to finish college and graduate. By one estimate, the rate ignores up to 50 percent of all enrolled students".[22]

References

- Kiss, Claire Reid; Fuller, Andrea (January 30, 2011). "Graduation rates decrease nationwide". The Massachusetts Daily Collegian. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- Snyder, Thomas D.; Dillow, Sally A. (April 2011). "Digest of Education Statistics, 2010, Introduction p.1" (PDF). NCES. Retrieved September 29, 2018.

- Bound, J.; Lovenheim, M. F.; Turner, S. (2010). "Why Have College Completion Rates Declined? An Analysis of Changing Student Preparation and Collegiate Resources". American Economic Journal: Applied Economics. 2 (3): 129–157. doi:10.1257/app.2.3.129. PMC 3140225. PMID 21785668.

- Astin, Alexander W.; Oseguera, Leticia (2005). Degree Attainment Rates at American Colleges and Universities (PDF) (rev. ed.). Higher Education Research Institute. ISBN 1878477358. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- Bound, J; Lovenheim, M.; Turner, S. E. (November 2007). "Understanding the decrease in college completion rates and the increased time to the baccalaureate degree" (PDF). University of Michigan Population Studies Center Research Report (07–626). Retrieved 15 October 2020.

- US Census Bureau 2009

- The Progress of Education Reform 2007 : Dropout prevention (2007)

- Federal Reserve Bank Chairman Ben Benarke

- Report from College Board's National Commission on Community College (2008)

- Bridget Terry Long, Michal Kurlaender (2008)

- Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, Paying for Performance: The Education Impacts of a Community College Scholarship Program for Low-income Adults, February 2012

- Center for Community College Student Engagement. "Promising practices for community college student success" (PDF). Retrieved 26 April 2013.

- Jenkins, Davis (December 2007). "Institutional Effectiveness and Student Success: A Study of High- and Low-Impact Community Colleges". Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 31 (12): 945–962. doi:10.1080/03601270701632057.

- Josipa Roksa, Juan Carlos Calciagno (2008)

- Douglas A Webber, Ronald G Ehrenberg (2009)

- "Vice President Biden Issues Call to Action to Boost College Graduation Rates Nationwide". US Department of Education.

- Mary Hough (March 22, 2011). "Boosting College Graduation Rates Across the Country". Democrats.org. Archived from the original on March 23, 2011.

- Duncan, Arne (March 2011). "College Completion Tool Kit" (PDF). United States Department of Education. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 25, 2011.

- "Transcript: State of the Union 2011". ABC News. January 27, 2011.

- A Stronger Nation Through Higher Education - How and why Americans much achieve a "big goal" for college attainment, The Lumina Foundation for Education, September 2010.

- Ryan, Camille; Siebens, Julie (March 2016). "Educational Attainment in the United States: 2015" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 22, 2017.

- "Graduation Rates Fall at One-Third of 4-Year Colleges". The Chronicle of Higher Education. December 5, 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2020.

External references

- The Progress of Education Reform 2007: Dropout prevention, August 2007

- Education Pay, The College Board, 2010

- Josipa Roksa and Juan Carlos Calciagno, Community College Research Center, Working paper #13, June 2008

- Report from College Board's National Commission on Community College, 2008

- Bridget Terry Long and Michal Kurlaender, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2008

- Douglas A Webber, Ronald G Ehrenberg, National Bureau of Economic Research, Working paper 15216, August 2009

- A Stronger Nation Through Higher Education - How and why Americans much achieve a "big goal" for college attainment, The Lumina Foundation for Education, September 2010