Djambi

Djambi (also described as "Machiavelli's chessboard") is a board game and a chess variant for four players, invented by Jean Anesto in 1975. The rulebook in French describes the game, the pieces and the rules in a humorous and theatrical way, clearly stating that the game pieces are intended to represent all wrongdoings in politics.

Rules

Material

The game is played on a 9×9 board whose central square (called "the maze") is marked with a different color or a sign. Each player has nine pieces:

- Some killers

- 1 Chief

Djambi chief piece

Djambi chief piece - 1 Assassin

Djambi assassin piece

Djambi assassin piece - 1 Reporter

Djambi reporter piece

Djambi reporter piece - 4 Militants .

Djambi militant piece

Djambi militant piece

- 1 Chief

- Some movers

- 1 Diplomat that moves living pieces. It is a very useful piece at the beginning of the game also called Agitator, or Troublemaker.

Djambi diplomat piece

Djambi diplomat piece - 1 Necromobile that moves corpses. Important piece in end of game as dead pieces stay as corpse on the board in this game.

Djambi necromobile piece

Djambi necromobile piece

- 1 Diplomat that moves living pieces. It is a very useful piece at the beginning of the game also called Agitator, or Troublemaker.

Objective

The objective of the game is to get absolute power by being the last chief alive on board. Although informal alliances can be temporarily agreed upon, there is no team: each player plays against the other players.

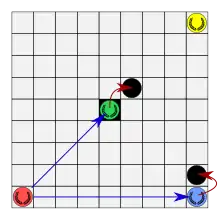

Start position

The pieces are placed in each corner of the board as shown in the picture above. Order of play is red - blue - yellow - green.

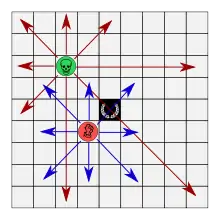

Movements

Each player, at his/her turn, moves one of his/her pieces, and can possibly capture a piece in this way. The militants move of one or two squares in the eight directions; the other pieces can move through any number of squares in the eight directions. A piece cannot jump above another piece.

Captures

The pieces are "killed" as soon as they are captured, but their "corpses" stay on the board (the pieces are turned upside down to show that they are "dead"). The militant kills by occupying the square of a piece (capture by replacement). He places the corpse on an unoccupied square of his choice, except on the central square (the "maze"). A militant cannot kill a chief in power (see the maze below).

- the chief kills and places the corpse in the same way as the militant.

- the assassin kills in the same way as the militant, but places the corpse in the square he comes from. This is the symbol that corpses by assassin tend to mess space at home in politics.

- the reporter kills by occupying one of the four squares next to the square of the piece he wants to kill (he cannot kill diagonally). The corpse stays in his square. The reporter can only kill at the end of his move. That means that if he is moved by the diplomat he must move again before killing and so cannot kill a piece that is directly orthogonal to him at the beginning of his move. The reporter can move without killing.

The diplomat and the necromobile cannot kill the other pieces but can move them.

- the diplomat can move another living piece by occupying its square (of course, he can only move the pieces of the other players). The piece is placed on any unoccupied square (except the maze if this piece is not a chief).

- the necromobile acts like a diplomat but only with the dead pieces (whatever the origin of the dead piece is). The corpses cannot be placed in the maze.

Death and surrounding of a chief

When a player kills the chief of another player, he/she takes control of the remaining living pieces of this one. At his/her turn, he/she will have the choice between using one of his/her own pieces, or using one of the captured pieces. When a player has no necromobile and his chief is surrounded by corpses, he is eliminated (except if he is in power, in the maze). His/her pieces now belong to the chief in power. If there is no chief in power, then the pieces cannot be moved or killed, until the moment when a chief takes the power, and captures them in that way (he keeps control on these pieces even if he leaves the maze).

The maze

The central square of the board is called the maze. Each piece can go through this square, but the chief is the only piece that can stop on it. A chief who is in the maze is a chief "in power". He plays one time after each player. For instance, if there are four players, he plays three times in a turn (if there are two players, he plays twice consecutively). When he leaves the maze, he loses this power. A chief in power takes control of the pieces of the surrounded chiefs, and keeps them after losing the power. A chief in power cannot be killed by a militant. The surrounding has no effect on him as long as he stays on the maze. An assassin, a troublemaker or a necromobile can go in the maze to kill or move a living chief or a chief corpse, the piece must make an additional move immediately, in order to leave the maze. The original rule humoristically states that it is done to avoid things like an assassin empowered in the maze. It is done in this order :

- the piece goes in the maze and the chief (corpse) is removed from the board

- the piece makes its free move to get out of the maze

- the chief/corpse is placed back on the board following the usual rule.

This order of actions allows placing the chief/corpse between the maze and the new position of the acting piece.

Alliances and betrayals

There can be informal agreements or alliances between the players, but there is no rule to prevent any betrayal.

End of the game

The game ends when a player has killed the chiefs of all of the other players.

Variants

Three-player variant

The pieces of the missing fourth player are "hostages". These pieces can be killed or moved by the pieces of the players. When the chief is captured, the normal rules to take control of them apply. The hostage chief can be placed in the maze, but it has no influence on the game.

Five-player variant

There is a five-player variant of djambi, called pentachiavel.

Yang Pî variant

There is a version of the game released by Roger Bartra and his collaborators called Yang Pî: The game of power. It was published in Mexico in 1979.