Door Peninsula

The Door Peninsula is a peninsula in eastern Wisconsin, separating the southern part of the Green Bay from Lake Michigan. The peninsula includes northern Brown and Kewaunee counties and all of Door County. It is the western portion of the Niagara Escarpment. Well known for its cherry and apple orchards, the Door Peninsula is a popular tourism destination. With the 1881 completion of the Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal, the northern half of the peninsula became an island.[2]

| Designations | |

|---|---|

| Official name | Door Peninsula Coastal Wetlands |

| Criteria | Door County § Wetlands |

| Designated | 10 June 2014 |

| Reference no. | 2218[1] |

Limestone outcroppings of the Niagara Escarpment are visible on both shores of the peninsula, but are larger and more prominent on the Green Bay side as seen at the Bayshore Blufflands. Progressions of dunes have created much of the rest of the shoreline, especially on the east side. Flora along the shore provide clear evidence of plant succession. The middle of the peninsula is mostly flat, cultivated land. Beyond the peninsula's northern tip is a series of islands, the largest of which is Washington Island. The partially submerged ridge extends farther north, becoming the Garden Peninsula in Upper Michigan.[3]

History

Archaeology

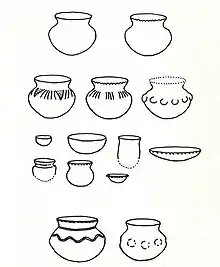

Archaeological evidence shows habitation of the peninsula and its islands by several different Native American groups.

Paleo-Indian artifacts were found at the Cardy Site, including four Gainey points.[4][5] The relationship between Gainey points[lower-alpha 1] and the more ubiquitous Clovis points[lower-alpha 2] is being researched, but there are some similarities.[6] Most of the material collected from the Cardy site by 2003 was made of Moline chert,[lower-alpha 3][7] which is not found in Wisconsin.[4] As of 2007, seven Clovis points have been found in the county.[8] Careful study of certain Paleo-Indian artifacts from western Wisconsin suggests that they were made in the Door peninsula and carried across the state.[9]

Artifacts from an ancient village site at Nicolet Bay Beach date to about 400 BC. This site was occupied by various cultures until about 1300 AD.[10]

In 246 B.C (±25 years), a dog was buried in a Native American burial site on Washington Island.[11]

Jean Nicolet

Two locations on the peninsula claim to be the landing site of French explorer Jean Nicolet in 1634, who was searching for a water route through North America to Asia: Horseshoe Island, which is part of Peninsula State Park, and Red Banks, which is about 7 miles north of what is now Green Bay.[12] Nicolet is remembered in Wisconsin lore for having mistaken the Ho-Chunk Indians for Asians and celebrating, believing he had reached the Far East. Nicolet had heard long before coming that the people living along these shores were called Winnebago ("the people from the stinking water") and, perhaps erroneously, "the People of the Sea". He concluded that this name meant they were from or living near the Pacific Ocean with its aromatic salt air and that they would be a direct link to the people of China, if not from China.[13]

Origin of the name

The name of the peninsula and the county comes from the name of a route between Green Bay and Lake Michigan. Humans, whether Native Americans, early explorers, or American ship captains, have been well aware of the dangerous water passage that lies between the Door Peninsula and Washington Island, connecting the bay to the rest of Lake Michigan. This small strait is now littered with shipwrecks. It was named by the Native Americans and translated into French as Porte des Morts: in English, "Death's Door".

Potawatomi and Menominee

Before and during the 19th century, various Native Americans occupied the Door Peninsula and nearby islands. 17th-century French explorers made contact with various tribes in the area. In 1634, the Jean Nicolet expedition landed at Rock Island. This is considered the first visit by men of European descent to what is now Wisconsin.[14] In 1665, Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard des Groseilliers spent the winter with the Potawatomi. In 1669, Claude-Jean Allouez also wintered with the Potawatomi. He mentioned an area called "la Portage des Eturgeons." In 1673, Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet stayed in the area about three months as part of their exploration.[15] In 1679, the party led by La Salle purchased food from a village of Potawatomi in what is now Robert La Salle County Park.[16] During the 1670s Louis André ministered to about 500 Native Americans at Rowleys Bay, where he erected a cross. The cross stood until about 1870.[17] Around 1690, Nicolas Perrot visited the Potawatomi on Washington Island. In 1720, Pierre François Xavier de Charlevoix visited the area with eight experienced voyageurs.[15]

Six Jesuit rings marked with letters or symbols[18] and turquoise colored glass trade beads were found on Rock Island in remains left by Potowatomi, Odawa, and Huron-Peton-Odawa Native Americans during the 17th and 18th centuries.[19] The remains of four Native American buildings were documented at the Rock Island II Site during 1969–1973 excavations.[20]

By the end of French rule over the area in 1763, the Potawatomi had begun a move to the Detroit area, leaving the large communities in Wisconsin. Later, some Potawatomi moved back from Michigan to northern Wisconsin. Some but not all Potawatomi later left northern Wisconsin for northern Indiana and central Illinois.[21]

In 1815, Captain Talbot Chambers was falsely reported[22] to have died fighting Blackhawk Indians on Chambers Island; the island was named for him in 1816.[23] In the spring 1833, Odawa on Detroit Island were baptized during an eight day visit by Frederic Baraga.[24] During an attack in 1835, one of two fishermen squatting on Detroit Island was shot and killed along with one or more Native Americans.[25] The other fisherman was rescued by a passing boat.[26] From the 1840s to the 1880s, the Clark brothers operated a fishing camp at Whitefish Bay that employed 30 to 40 fishermen. Additionally, 200–300 Potawatomi extracted fish oil from the fish waste at the camp.[27]

The Menominee ceded their claim to the Door Peninsula to the United States in the 1836 Treaty of the Cedars after years of negotiations with the Ho-Chunk and the U.S. government over how to accommodate the incoming populations of Oneida, Stockbridge-Munsee, and Brothertown peoples who had been removed from New York.[28] As a result of this treaty, settlers could purchase land, but many fishermen still chose to live as squatters. At the same time, the more decentralized Potawatomi were divested of their land without compensation. Some Potawatomi as late as 1845 made sure to visit and gamble with the Menominee shortly after the periodic annuity payments were issued.[29] Many emigrated to Canada because of multiple factors. One factor was invitations from Native Americans already in Canada for the Potawatomi to join them. Another was British policies to invite and encourage as much Indian emigration from the United States as possible. Even prior to their final emigration, many Potowatomis had periodically migrated into Canada to receive compensation related to their service on the British side during the War of 1812 and to pledge their continued loyalty. Another factor was a desire to avoid the harsh terms of the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, which compensated the Wisconsin Potowatomi with less than what was paid to Potowatomi from the Chicago area. Although not all Potawatomi participated in the Treaty of Chicago, it was federal policy that any who did not relocate westward as the treaty stipulated would not be compensated for their land. Additionally, some preferred the climate of the Great Lakes area over that of the Plains, and American governmental policy for the area beginning in 1837 tended towards forced rather than voluntary Indian removal.[lower-alpha 4] Moving to Canada became a way to stay in the Great Lakes area without risking removal.[30][29]

Potawatomi Chief Simon Kahquados traveled to Washington, D.C. multiple times in an attempt to get the land back. In 1906, Congress passed a law to establish a census of all Potawatomi formerly living in Wisconsin and Michigan as a first step toward compensation. The 1907 "Wooster" roll, named after the clerk who compiled it, documented 457 Potawatomi living in Wisconsin and Michigan and 1423 in Ontario. Instead of returning the land, a meager monthly payment was issued.[30] Although Kahquados was unsuccessful, he increased public awareness of Potawatomi history. In 1931, 15,000 people attended his burial in Peninsula State Park.[31]

County border adjustments

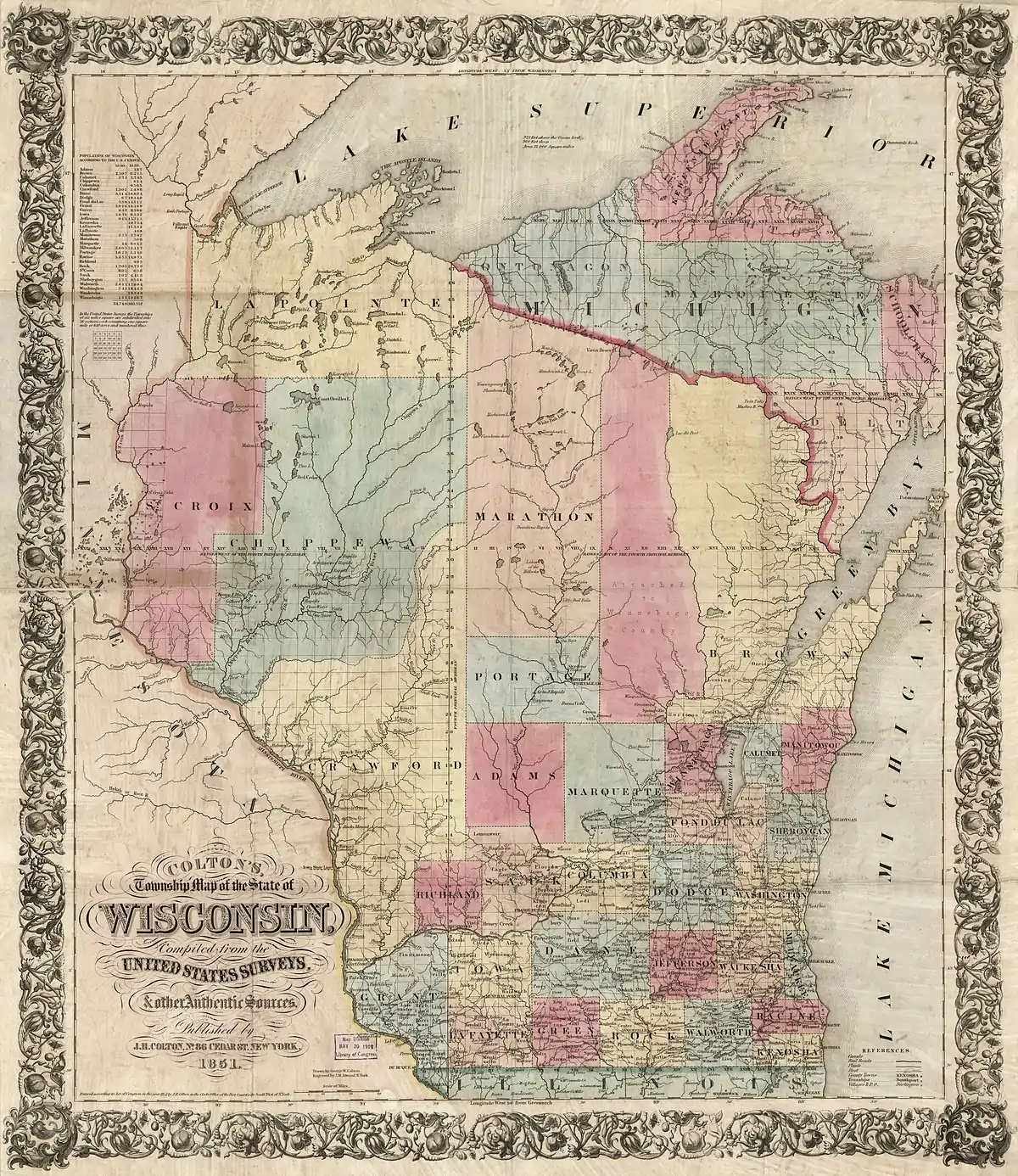

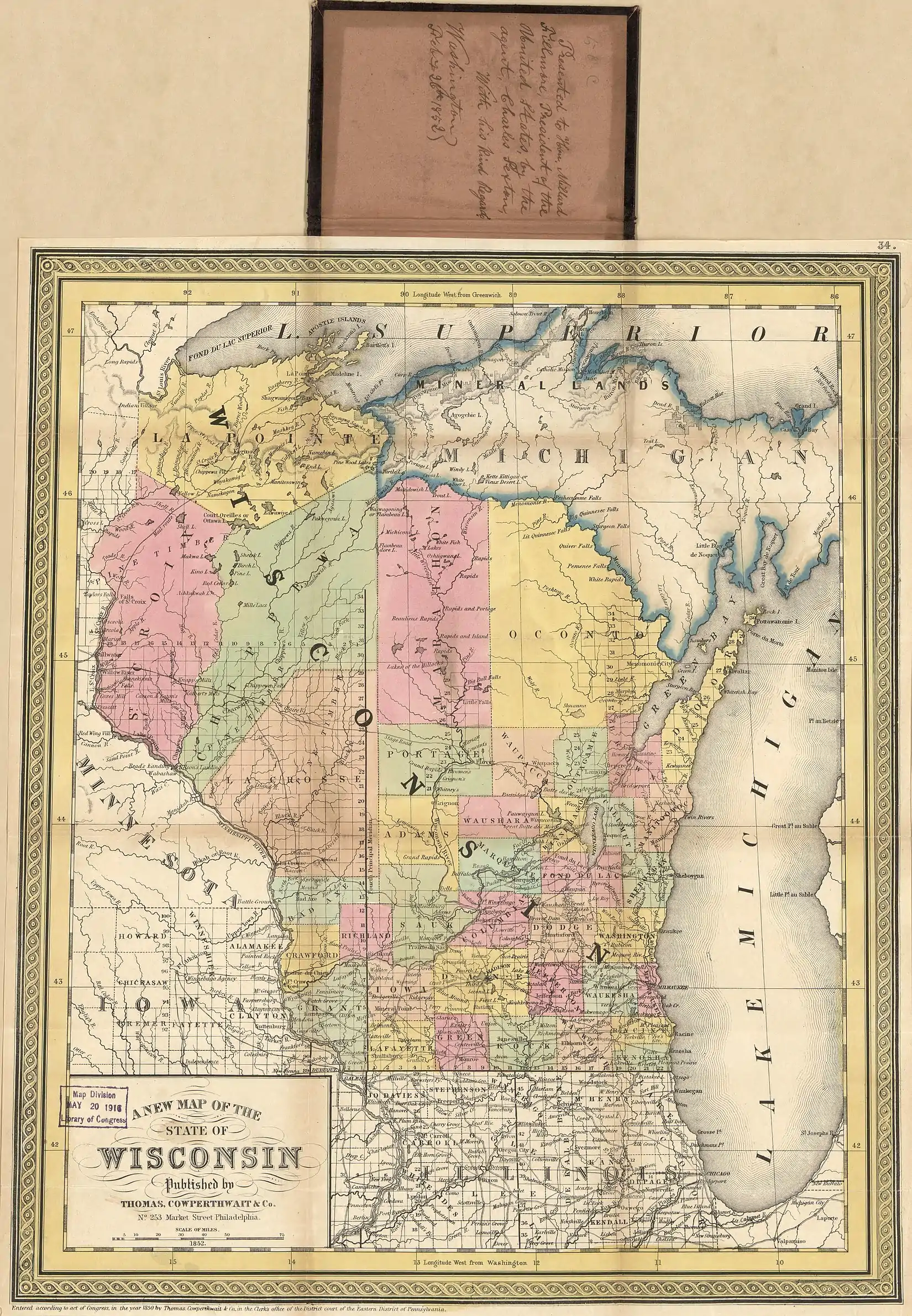

In 1818, Michilimackinac and Brown counties were formed by the Michigan territorial legislature. The border between the two ran through the peninsula at Sturgeon Bay. What is now the southern part of Door County was in Brown County, while the northern part was in Michilimackinac County.

In 1836, the northern part of Door County was taken from Michilimackinac County and added to Brown County as part of an overall border adjustment limiting Michilimackinac to areas within the soon-to-be-reduced Michigan Territory.

When Door County was separated off from Brown County in 1851, it included what is now Kewaunee County. Kewaunee County was separated off of Door County in 1852.[34]

Although the Door–Marinette county lines within the Wisconsin part of Green Bay were assigned to the "center of the main channel of Green Bay,"[35] not all maps drew the positions of the islands and the main channel of Green Bay correctly.[lower-alpha 5] In particular, some once incorrectly considered Green Island in what is now the town of Peshtigo in Marinette County to be in the town of Egg Harbor in Door County.[36]

In 1923, Michigan claimed ownership of Plum, Detroit, Washington, and Rock islands in Door County, although it did not take possession of them. In 1926, the Supreme Court dismissed Michigan's claim. In doing so, the court mistakenly appeared to award islands north of Rock Island in Delta County to Wisconsin (and by extension to Door County). Door County never assumed jurisdiction over these Michigan islands, and the matter was fixed again before the Supreme Court in the 1936 Wisconsin v. Michigan decision,[37] which left governance of the islands in Door and Delta counties as they had been before the litigation.

The more tourism-dominated northern part of the peninsula was acculturated from the professional and business classes of the tourists, while the more agriculture-dominated southern remained more rural in character.[38] Due to economic, ethnic, and cultural differences between the northern and southern parts of the present-day Door County, arguments are sometimes started about the most appropriate place to draw the Door–Kewaunee line.[39]

Geography

Structures on high points

- A tower on Brussels Hill is owned by the Wisconsin Public Service Corporation.[41]

- Boyer Bluff Lighthouse is an 80 foot (24 meters) tall skeleton tower[42] on Washington Island's Boyer Bluff 45.41998°N 86.93595°W, elevation 722 ft (220 meters)

- "The Mountain" at Mountain Park in Washington Island is the highest point on the island and has a lookout tower.[43]

- Eagle Bluff Lighthouse on Eagle Bluff 45.17415°N 87.22205°W, elevation 597 ft (182 meters)

- Pottawatomie Light on Pottawatomie Point on Rock Island.[44]

- A wind turbine project on the escarpment was completed in 1999. At the time the 30.5-acre (12.3-ha) Rosiere Wind Farm was the largest in the eastern United States.[45]

Other high points

- Deathdoor Bluff 45.29637°N 87.06539°W, elevation 728 ft (222 meters)

- Ellison Bluff 45.25888°N 87.10234°W, elevation 587 ft (179 meters)

- Mount Lowe 44.86805°N 87.37538°W, elevation 728 ft (222 meters)

- Sister Bluffs 45.1861°N 87.154°W, elevation 581 ft (177 meters)

- Svens Bluff 45.13416°N 87.23233°W, elevation 633 ft (193 meters)

- Table Bluff 45.29915°N 87.01651°W, elevation 623 ft (190 meters)

- Certain other high points are currently unnamed[46]

Kewaunee County

- Cherneyville Hill44.42583°N 87.73065°W, elevation 1,014 ft (309 meters)

- Dhuey Hill44.63777°N 87.62426°W, elevation 912 ft (278 meters)

- Montpelier Hills44.43583°N 87.71481°W, elevation 951 ft (290 meters)

Caves and sinkholes

| Sea caves of the Door Peninsula and Rock Island | |||

| |||

A pit cave containing the skeletal remains of both present-day and pre-Columbian animals opens at the southern base of Brussels Hill. It is the deepest known[14] pit cave and the fourth-longest known cave of any sort in Wisconsin. It was discovered by excavating three sinkholes in an extensive project.[47][48] Hundreds of sinkholes in Door County have been found and marked on an electronic map.[49] Most sinkholes on the peninsula are formed by gradual subsidence of material into the hole rather than a sudden collapse. Some are regularly filled by tilling or natural erosion, only to subside more due to meltwater or heavy rain.[50]

Many caves are found in the escarpment.[51][52] One of them, Horseshoe Bay Cave, is Wisconsin's second-longest and contains a 45-foot-high underground waterfall.[53][54][55] Horseshoe Bay Cave is home to rare invertebrates. Several tiny caves at Peninsula State Park are open and accessible to the public. Eagle Cave is larger but opens midway up the escarpment.[56]

Only one cave not formed by karst or lakeshore erosion has been discovered in Door County. It opens in the basement of a nursing home in Sturgeon Bay.[57]

Waters

Sturgeon Bay and Little Sturgeon are considered biodiversity hotspots because they support a large number of different fish species.[58]

North of the peninsula, warm water from Green Bay flows into Lake Michigan on the surface, while at the same time, cold lakewater enters Green Bay deep underneath.[59] This is a major reason why oxygen levels in the bay are often too low.[60]

Salmon

Beginning in 1964, first coho and then Chinook salmon were stocked in Lake Michigan.[61] New Chinook fingerling stocking in the spring and egg and milt collection from late September to early November primarily takes place at the Strawberry Creek Chinook Facility in southern Door County. The facility is a public attraction during stocking and collection times.[62]

In recent years there has been concern that the alewife population will not support the salmon population,[63] especially as the Chinook population has already collapsed in Lake Huron.[64]

Chinook salmon are sought after by tourists enjoying chartered fishing trips.[65] Several state record salmon have been caught out of Door County waters on the Lake Michigan side. In 1994 the state record Chinook was taken; it weighed 44 pounds, 15 ounces, and was 47.5 inches long. In 2016 the state record for pinook (a hybrid of the pink and Chinook salmons) was set at a weight of 9 pounds, 1.6 ounces, and 27.87 inches.[66] In 2018, Kewaunee County ranked first in the state with 26,557 Chinook salmon caught. Door County ranked second with 14,268 fish caught.[67]

| Commercial and recreational fishing | |||

| |||

Reefs and shoals in Door County waters

- Dunlap Reef 44.8375°N 87.38815°W

- Fisherman Shoal 45.36443°N 86.77984°W

- Four Foot Shoal 45.16082°N 87.00206°W

- Hanover Shoal 45.14804°N 87.31705°W

- Horseshoe Reefs 45.2211°N 87.20761°W

- Larsons Reef 44.88833°N 87.47621°W

- Middle Shoal 45.31665°N 86.93623°W

- Monument Shoal 44.99166°N 87.37371°W

- Nine Foot Shoal 45.27638°N 86.95595°W

- Outer Shoal 45.23388°N 86.96289°W

- Sherwood Point Shoal 44.91249°N 87.46205°W

- Sister Shoals 45.20027°N 87.16956°W

- Waverly Shoal 45.28193°N 86.95178°W

Other fishing

Walleye found in the Sturgeon Bay and Little Sturgeon area had 87% more PCBs[lower-alpha 6] than walleye from the western side of Green Bay at the mouth of the Oconto River. This fits what is known about the distribution of PCBs which spread from industries in the Fox River Valley.[68]

Round gobies eat mussels off the rocky shoreline.[69] In 2014 the state speargun record for the invasive round goby was taken by out of Door County waters on the Lake Michigan side. It weighed 5.0 ounces and was 8.25 inches long.[66]

Lake whitefish and yellow perch are caught commercially.[70] Lake whitefish are also caught commercially by ice fishing.[71] Tagging studies have shown whitefish migrating from Big Bay de Noc which has less food to the plentiful waters off the peninsula.[72]

Remains of sturgeon, catfish, sucker, smallmouth bass, white bass, walleye, and drum left behind by Native Americans were found near North Bay in the 1960s.[73]

Surfing

Lake Michigan shoreline is used for lake surfing.[74] One guidebook names the shore off Cave Point County Park as the best surfing area.[26] Another water sport is windsurfing.[75]

Climate

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Lake breeze

On hot summer days, cool lake breezes start in around noon and grow more intense by mid-afternoon. This effect can be noticed at the shoreline and around a mile or so inland.[77] Although lake breezes are capable of penetrating considerably further inland, they are able to heat up quickly after passing onto land. After as little as a mile of travel inland, they may be nearly as warm as the air they push away.[78] When a lake breeze encounters an inward curving shoreline, such as at Sister Bay, the breeze becomes more intense. The curve of the shore guides the breezes from opposing sides of the bay and makes them converge upon each other at the middle.[79]

Rare snails

From 1996 to 2001, researchers identified 69 species of snails in Door County, the most out of the 22 counties in the study. Most of these were found on rock outcrop habitats. Ranking second was Brown County with 62 species. 48 species were found in Kewaunee County, ranking eighth. Slugs were found in all three counties. Peninsula State Park is home to the northernmost known population of Strobilops aenea. The species Vertigo hubrichti and Vertigo morsei are endemic to the upper Midwest. These two species had the highest occurrence frequencies along the Door and Garden Peninsulas. Door County is also home to several uncommon species from the genus Oxychilus, which is non-native and introduced from Europe. One was found near a vacation home and may have been introduced by landscape plantings. Within Door County, Brussels Hill, North Kangaroo Lake, Rock Island and the escarpment with its cool algific habitat supports populations of rare snails.[80][14] Out of 63 locations in Door County where snails were found, the most species (28) were located on a cliff in Rock Island.[81]

Notes

- For more on Gainey points, see the entry on Gainey points on projectilepoints.net

- For more on Clovis points, see the entry on Clovis points on projectilepoints.net

- For more on Moline chert, see the entry on Moline chert on projectilepoints.net

- See Forest County Potawatomi Community for who are descended from those chose to remain in Wisconsin despite the risk of Indian removal.

- For an example of a map assigning Green Island to Door County, see Johnson’s Map of Michigan and Wisconsin, 1863.

- This figure came from comparing an average concentration of PCBs from the whole body of the fish.

References

- "Door Peninsula Coastal Wetlands". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

- Seeing The Light - Sturgeon Bay Ship Canal Pierhead Light

- The Niagara Escarpment Archived 2008-05-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Life During The End Of The Ice Age: The Cardy site could inform archaeologists about how humans dealt with a challenging environment., American Archaeology Vol. 14, No. 3, Fall 2010

- Older than the Egyptian pyramids, stone tools found in Sturgeon Bay go on display by Liz Welter, Green Bay Press-Gazette Aug. 14, 2018

- Iowa's Archaeological Past by Lynn M. Alex, Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2000, p. 50

- Midwest Archeological Conference, 49th Annual Meeting, Milwaukee, October 16–19, 2003, p. 26 (p. 27 of the pdf)

- A Survey of Wisconsin Fluted Points by Thomas J. Loebel, Current Research in the Pleistocene 24:118–119

- Sourcing of an Unidentified Chert from Western Wisconsin Paleo-Indian Assemblages by Eric Bailey, Journal of Undergraduate Research 5, p. 255–260

- Soucek, G. (2011). Door County Tales: Shipwrecks, Cherries and Goats on the Roof. American Chronicles. Arcadia Publishing Incorporated. ISBN 978-1-61423-383-1. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Analysis of Canis sp. remains recovered from the Richter Site (47DR80), a North Bay Phase Middle Woodland occupation on Washington Island, Wisconsin by Emily M. Epstein, Wisconsin Archaeologist, 2010

- "History". Archived from the original on March 1, 2009. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- "UW - Green Bay - Wisconsin's French Connections Jean Nicolet Statue". Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved April 26, 2008.

- A Guide to Significant Wildlife Habitat and Natural Areas Of Door County, Wisconsin, March, 2003, by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources Sturgeon Bay Service Center, p. 128, p. 52, p. 23, p. 127 and pp. 52, 83, 85, and 99 (note: pagination in the pdf is one page past the numerical pagination)

- Door County Comprehensive Plan 2030. Chapter 3 – Historical and Cultural Resources. Volume II, Resource Report., Table 3.1: Timeline of Historic Events in Door County, pp. 19–20 (pp. 4–5 of the pdf)

- Robert LaSalle County Park kiosk historical notes

- Liberty Grove Historical Museum, small sign engraved on the replica cross

- Iconographic (Jesuit) Rings in European/Native Exchange by Carol I. Mason and Carol I. Kathleen L. Ehrhardt, in French Colonial History 10, 2009, a photo of one of rings together with five other rings from other sites is on p. 56 of the article (p. 2 of the pdf), p. 63 of the article (p. 9 of the pdf) associates the rings with the Pottawatomi and Ottawa, and details about each ring are described on pp. 72–73 of the article (pp. 18–19 of the pdf)

- Stylistic and Chemical Investigation of Turquoise-Blue Glass Artifacts from the Contact Era of Wisconsin by Walder, Heather, Midcontinental Journal of Archaeology 38(1) Spring 2013 p. 123 (p. 5 of the pdf) For pictures of the two remelted pendents found at Rock Island and possibly of a later origin than the beads, see p. 127 (p. 19 of the pdf)

- Mason, Ronald J. (1986). Rock Island: Historical Indian Archaeology in the Northern Lake Michigan Basin. Kent State University Press.

- Edmunds, R. David (1988). The Potawatomis: Keepers of the Fire. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press (Civilization of the American Indian Series); ISBN 0-8061-2069-X

- Forgotten Charms of Chambers Island by Patty Williamson, Peninsula Pulse, August 25th, 2017

- Town of Gibraltar 20-Year Comprehensive Plan, chapter 2, p. 3 (p. 35 of pdf)

- Some Missionary Activities of the Lake Superior Region of the United States by Mary Stilla Martin, M.A. Thesis, Marquette University, Page 60 (page 76 of the pdf) and The Life of Bishop Frederic Baraga by Glenn Phillips, page 3, Bishop Baraga Association, 1997

- Book Excerpt, Island Tales: “History and Anecdotes of Washington Island” by Jessie Miner

- Exploring Door County by Craig Charles, NorthWord Press, Minoqua, Wisconsin, 1990, pages 178 (Detroit Island) and 158 (surfing)

- Whitefish Dunes State Park History, Wisconsin DNR, January 7, 2015

- "Menominee Treaties and Treaty Rights". Indian Country Wisconsin. Retrieved October 5, 2018.

- Chapter on The Migrations: 1835–1845 in Place of refuge for all time by James A. Clifton, University of Ottawa Press, 1975, pages 65, 73, and 86–87 (pages 2, 10, and 23–24 of the pdf)

- "Potawatomi Migration from Wisconsin & Michigan to Canada". Geni. Retrieved January 23, 2019.

- "Kahquados, Chief Simon". Wisconsin Hometown Stories: Door County. Wisconsin Public Television. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- A Gazetteer of the Province of Upper Canada by David William Smyth, New York: Prior and Dunning, 1813

- The American Gazetteer by Jedidiah Morse, Boston: S. Hall and Thomas & Andrews, 1797, page 584

- Door County Board of Supervisors Comprehensive Planning Program by the Door County Board of Supervisors, Assisted by the Department of Resource Development, Chapter Three, "Development in Door County," Section "Political Boundaries," 1964, p. 49

- Private and Local Acts Passed by the Legislature of Wisconsin, Chapter 114, Section 2, 1879, p. 113, detailing the county borders for Marinette County

- Discovering Door County's past: a comprehensive history of the Door Peninsula in two volumes, Volume 1 by M. Marvin Lotz, Holly House Press, 1994, p. 76

- Wisconsin: Individual County Chronologies, Wisconsin Atlas of Historical County Boundaries by John H. Long, Peggy Tuck Sinko, Gordon DenBoer, Douglas Knox, Emily Kelley, Laura Rico-Beck, Peter Siczewicz, and Robert Will, Chicago: The Newberry Library, 2007

- Women in Print by James P. Danky, Wayne A. Wiegand, and Elizabeth Long, chapter A "Bouncing Babe," a "Little Bastard": Women, Print, and the Door-Kewaunee Regional Library, 1950–52 by Christine Pawley, pages 210–211 (pages 4-5 of the pdf), University of Wisconsin Press, 2006.

- Drawing Lines: Door County’s Geographic Rivalries, Myles Dannhausen Jr., Door County Living – July 1st, 2011

- Wardius, K.; Wardius, B. (2013). Wisconsin Lighthouses: A Photographic and Historical Guide, Revised Edition. Wisconsin Historical Society Press. pp. 100–25. ISBN 978-0-87020-610-8. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- Resolution No. 2018-16, Door County Board of Supervisors, March 27, 2018

- Boyer Bluff (Wisconsin), United States Lighthouse Society

- Washington Island Comprehensive Outdoor Recreation Plan (2011-2015), Town of Washington, October 2011, page 12 (page 18 of the pdf)

- Geology of Washington Island and its Neighbors, Door County Wisconsin by Robert R. Schrock, Transactions of the Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters XXXII, 1940, pp. 205 and 216 (pp. 11 and 24 of the pdf)

- "Rosière Wind Farm". Madison Gas and Electric. Retrieved July 8, 2009. and "MGE Celebrates 10th Anniversary of State's First Wind Farm". Wisconsin Ag Connection. July 7, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2009.

- PeakVisor Door County Named Mountains

- Wisconsin Section of the American Institute of Professional Geologists Field Trip, May 30–31, 2009, p. 85 (p. 87 of the pdf)

- Beneath the Door Peninsula: The Story of Paradise Pit Cave by Gary K. Soule, p. 239–246, NSS News, June 1986

- Web-Map of Door County, Wisconsin ... For All Seasons!, Door County Land Information Office, Accessed September 7th, 2019

- p. 23 (p. 27 of the pdf) of Effects of Geological Processes on Environmental Quality, Door Peninsula, Wisconsin by Ronald D. Stiegliz in The Silurian Dolomite Aquifer of the Door Peninsula: Facies, Sequence Stratigraphy, Porosity, and Hydrogeology: Field Trip Guidebook (Revised Version) for the 1996 Fall Field Conference of the Great Lakes Section of the SEPM, Green Bay, Wisconsin and Pre-meeting field trip for the 1997 Meeting of the North-Central Section of the GSA, Madison Wisconsin

- Geology and Ground Water in Door County, Wisconsin, with Emphasis on Contamination Potential in the Silurian Dolomite By M. G. Sherrill, United States Geological Survey Water-Supply Paper 2047. 1978, locations of caves are shown on Plate 1

- Man Goes Deep To Explore, Preserve The Hidden Treasures Of Door County’s Caves, by Joel Waldinger, October 14, 2014, Wisconsin Life PBS

- Door County Coastal Byway Interpretive Master Plan by Schmeeckle Reserve Interpreters, p. 36, (p. 42 of the pdf), 2014

- Horseshoe Bay Cave tour video, August 9, 2017, Door County WI Travel Show series, YouTube, Door County Visitor Bureau

- Door County's Legendary Horseshoe Bay Cave (Tecumseh Cave) Egg Harbor, WI by Gary K. Soule, Prepared for the Spelean History Section Series 22, July 2014

- Wisconsin Underground: A Guide to Caves, Mines, and Tunnels in and Around the Badger State by Doris Green, Black Earth, Wisconsin: Trails Books, 2000, p. 47

- Dorchester Cave–An Unusual Urban Discovery, NSS News, June 2010, p. 18–24

- Hotspots and bright spots in functional and taxonomic fish diversity by Katya E. Kovalenko, Lucinda B. Johnson, Valerie J. Brady, Jan J. H. Ciborowski, Matthew J. Cooper, Joseph P. Gathman, Gary A. Lamberti, Ashley H. Moerke, Carl R. Ruetz III, and Donald G. Uzarski, Freshwater Science 38(3), July 2, 2019, pages 484 and 486 (pages 5 and 7 of the pdf)

- Currents and Temperatures in Green Bay, Lake Michigan, Journal of Great Lakes research 11(2):97–109, 1985, by page 108 (page 12 of the pdf)

- Currents and heat fluxes induce stratification leading to hypoxia in Green Bay, Lake Michigan by H. R. Bravo, S. A. Hamidi, J. V. Klump, and J. T. Waples, E-proceedings of the 36th IAHR World Congress, 28 June – 3 July 2015, The Hague, the Netherlands

- The Salmon Experiment: The invention of a Lake Michigan sport fishery, and what has happened since, Updated Jan 21, 2019; Posted Apr 18, 2011 By Howard Meyerson, The Grand Rapids Press

- Chinook Salmon Program at Strawberry Creek by Jim Lundstrom, Peninsula Pulse, October 16, 2015, also see the brochure for the Strawberry Creek Strawberry Creek Chinook Facility, Wisconsin DNR

- Red flags signal possible trouble for Lake Michigan salmon where chinooks are king, by Howard Meyerson, The Grand Rapids Press, Updated Jan 21, 2019; Posted Apr 17, 2011

- Charter Captain Meeting March 12, 2015, see pp. 56–57, Archived November 1, 2019 also see Lake Huron’s Chinook salmon fishery unlikely to recover due to ongoing food shortage by Jim Erickson, March 14, 2016

- It’s No Fish Tale… Charter Boat Captain Is Living His Dream by Joel Waldinger, November 5, 2015, Wisconsin Life, PBS

- Wisconsin Record Fish List, September 2018, Wisconsin DNR (The records are current as of September 2018.)

- Kewaunee/Door Peninsula Again Top in Chinook Harvest by Kevin Naze, Peninsula Pulse, May 1, 2019

- Association between PCBs, Liver Lesions, and Biomarker Responses in Adult Walleye (Stizostedium vitreum vitreum) Collected from Green Bay, Wisconsin by Mace G. Barron, Michael Anderson, Doug Beltman, Tracy Podrabsky, William Walsh, Dave Cacela, and Josh Lipton, April 13, 1999, Journal of Great Lakes Research 3, p. 11 (p. 12 of the pdf)

- Impact of Round Gobies (Neogobius melanostomus) on Dreissenids (Dreissena polymorpha and Dreissena bugensis) and the Associated Macroinvertebrate Community Across an Invasion Front by Amanda Lederer, Jamie Massart, and John Janssen, Journal of Great Lakes Research 32:1–10, 2006 (also see the revision) and Impacts of the Introduced Round Goby (Apollonia melanostoma) on Dreissenids (Dreissena polymorpha and Dreissena bugensis) and on Macroinvertebrate Community between 2003 and 2006 in the Littoral Zone of Green Bay, Lake Michigan by Amanda M. Lederer, John Janssen, Tara Reed, and Amy Wolf, Journal of Great Lakes Research 34(690-697), 2008, pp. 690–697

- WI Natural Resources Board Agenda Item #6.B. by Bradley Eggold, August 2019 webcast

- Commercial Ice Fishing Has Door County Resident Hooked by Joel Waldinger, December 15, 2017

- Lake whitefish feeding habits and condition in Lake Michigan by Kelly-Anne Fagan, Marten A. Koops, Michael T. Arts, Trent M. Sutton, and Michael Power, Advanced Limnology 63, 2008, pp. 401–410 (pp. 3 and 12 of the pdf)

- The Inland Shore Fishery of the Northern Great Lakes: Its Development and Importance in Prehistory by Charles E. Cleland, American Antiquity 47(4), October, 1982, p. 770, (p. 11 of the pdf)

- Surf’s Up in Door, Ryan Heise, Door County Living – August 1st, 2018

- Sturgeon Bay Visitor Center News, Sturgeon Bay Visitor Center, archived February 8, 2020

- "NASA Earth Observations Data Set Index". NASA. Retrieved January 30, 2016.

- The Land and Sea Breeze of Door Peninsula, Wisconsin by Eric R. Miller, Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 20(5), 1939, pp. 209–211

- The climatology and prediction of the Chicago lake breeze by W. A. Lyons, Journal of Applied Meteorology 11, December 1972, p. 1262 (p. 4 of the pdf)

- Some Uses of High-Resolution GOES Imagery in the Mesoscale Forecasting of Convection and Its Behavior by James F. W. Purdom, Monthly Weather Review 104 December 1976, p. 1476 (p. 3 of the pdf)

- Terrestrial gastropod fauna of Northeastern Wisconsin and the Southern Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Jeffrey C. Nekola, 2003, American Malacological Bulletin 18(1-2)

- Terrestrial gastropod richness of carbonate cliff and associated habitats in the Great Lakes region of North America by J. C. Nekola, Malacologia 41(1), 2000, p. 246 (p. 16 of the pdf)

.jpg.webp)