Doug DeCinces

Douglas Vernon DeCinces (/dəˈsɪn.seɪ/ də-SIN-say; born August 29, 1950) is an American former professional baseball player. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) as a third baseman from 1973 to 1987 for the Baltimore Orioles, California Angels and St. Louis Cardinals.[1] He also played for one season in the Nippon Professional Baseball league for the Yakult Swallows in 1988.

| Doug DeCinces | |||

|---|---|---|---|

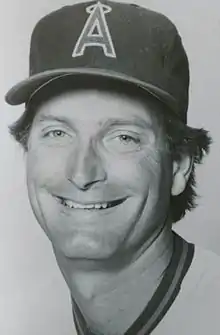

DeCinces in 1986 | |||

| Third baseman | |||

| Born: August 29, 1950 Burbank, California | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 9, 1973, for the Baltimore Orioles | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 4, 1987, for the St. Louis Cardinals | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .259 | ||

| Home runs | 237 | ||

| Runs batted in | 879 | ||

| Teams | |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

In 1982, DeCinces won the Silver Slugger Award, which is awarded annually to the best offensive player at each position and, was a member of the 1983 American League All-Star team. In 2006, he was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame.[2]

Professional baseball career

DeCinces played PONY League Baseball and Colt League Baseball in Northridge, California, with fellow major league player Dwight Evans. He attended and played at Monroe High School in Sepulveda, California and Los Angeles Pierce College, and is in Pierce College's Athletic Hall of Fame.

He began his major league career at the age of 23 with the Baltimore Orioles late in the 1973 season.[1] When the Orioles' Hall of Fame third baseman, Brooks Robinson retired at the end of the 1977 season, DeCinces was given the difficult task of replacing the legendary player.[3] Despite being booed by Orioles fans in his first game as Robinson's replacement, he endured to play for the Orioles for a total of nine seasons.[3]

On June 22, 1979, DeCinces hit a game-winning home run at Memorial Stadium off Detroit Tigers reliever Dave Tobik. The Orioles were trailing the Tigers 5-3 going into the bottom of the ninth inning. With one out, Ken Singleton hit a solo home run off Tobik to bring the Orioles within one. Eddie Murray reached base on a single, and, with two outs, DeCinces hit a two-run home run to give the Orioles a 6-5 victory.[4] The win has been called "the night Oriole Magic was born."[5] DeCinces said years later that the game and his home run "triggered something" and that "the emotion just multiplied from there," adding that the ensuing atmosphere of excitement was in no small part due to the excited call of the home run by announcers Bill O'Donnell and Charley Eckman on the Orioles' radio network.[6][7] The Orioles went on to win the American League pennant in 1979.

DeCinces tagged out Dan Ford who was attempting to advance to third base on a force play that ended Game 2 of the 1979 American League Championship Series.[8]

In 1981, DeCinces got into a feud with Jim Palmer after DeCinces missed a line drive hit by Alan Trammell in a game against the Tigers. According to DeCinces, Palmer "was cussing me out and throwing his hands in the air" after the play. "Those balls have to be caught," Palmer told a paper. "Doug is reluctant to get in front of a ball." "I'd like to know where Jim Palmer gets off criticizing others," DeCinces responded. "Ask anybody–they're all sick of it. We're a twenty-four man team–and one prima donna. He thinks it's always someone else's fault." The feud simmered until June, when Weaver said, "I see no cause for concern. The third baseman wants the pitcher to do a little better and the pitcher wants the third baseman to do a little better. I hope we can all do better and kiss and make up...The judge gave me custody of both of them."[9] Palmer ultimately blamed Robinson for the dispute: "If Brooks hadn't been the best third-baseman of all time, the rest of the Orioles wouldn't have taken it for granted that any ball hit anywhere within the same county as Brooks would be judged perfectly, fielded perfectly, and thrown perfectly, nailing (perfectly) what seemed like every single opposing batter."[10]

Both DeCinces and Ford were exchanged for each other in a trade that also sent Jeff Schneider from the Orioles to the Angels and was announced on January 28, 1982.[11] The deal was delayed when Ford requested additional compensation because the Orioles were not one of six teams listed in his contract to which he could be traded without approval. The transaction became official upon his approval two days later on January 30.[12] DeCinces' departure allowed rookie Cal Ripken Jr. to become the Orioles' new starting third baseman.[11]

DeCinces was a member of the American League All Star Team in 1983.[1] Released by the Angels on September 23, 1987, he concluded his major league career by playing in four games for the St. Louis Cardinals late in the 1987 season.[1] In total, DeCinces played for 15 seasons (1973–1987) in the major leagues for three different teams, including nine years with the Orioles and six years with the Angels.[1]

Also in 1982, DeCinces hit three home runs in a game twice within a five day span as a member of the California Angels, on August 3 in a 5-4 loss to the Minnesota Twins and on August 8 in a 9-5 victory over the Seattle Mariners.

In 1988 DeCinces played for the Yakult Swallows in Japan. He missed the final two months of the season because of back problems and, on his doctors' advice, retired from baseball at the age of 37.[13] His experiences in Japan led to him being hired as a consultant for the 1992 film Mr. Baseball, about a veteran American ballplayer who is traded to a Japanese baseball club and is forced to contend with overwhelming expectations and cultural differences during the team's run at the pennant.

DeCinces twice finished in the top 25 voting for the American League Most Valuable Player, finishing third in 1982 and 11th in 1986 while playing for the California Angels.[1] In 1982 he also won the Silver Slugger Award.[1]

He was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame on August 26, 2006.

Insider trading trial

On August 4, 2011, DeCinces, along with three others, was charged by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) with insider trading ahead of a company buyout. In a civil suit, the SEC alleged that DeCinces and his associates made more than $1.7 million in illegal profits when Abbott Park, Ill.-based Abbott Laboratories Inc. announced its plan to purchase Advanced Medical Optics Inc. through a tender offer.[14] Without admitting or denying the allegations, DeCinces agreed to pay $2.5 million to settle the SEC's charges.[15]

In November 2012, DeCinces received a criminal indictment on insider trading related to the same incident and was charged with securities fraud and money laundering.[16] On May 12, 2017, after a nearly two-month trial, a federal court jury in Santa Ana, California, found him guilty on 13 felony counts.[17][18] He was also called to testify in the trial of others implicated in the insider trading case.[19] On August 12, 2019, DeCinces was sentenced to eight months of home detention and ordered to pay a $10,000 fine.[20] Hall-of-Fame former ballplayer Rod Carew extolled the charitable contributions of DeCinces at the sentencing, telling the court, "I am here because he has done so much more for other people".[21]

Career statistics

| Years | Games | PA | AB | R | H | 2B | 3B | HR | RBI | BB | SO | AVG | OBP | SLG | FLD% |

| 15 | 1649 | 6534 | 5809 | 778 | 1505 | 312 | 29 | 237 | 879 | 618 | 904 | .259 | .329 | .445 | .959 |

In postseason play, in 23 games, in 3 ALCS and 1 World Series, he batted .270 (24-for-89) with 13 runs, 2 home runs and 9 RBI.

Further reading

- Comak, Amanda. "DeCinces enjoying life as businessman". MLB.com. Retrieved on Thursday, August 14, 2008.

References

- "Doug DeCinces statistics". Baseball Reference. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- "Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame at MLB.com". mlb.com. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Joseph, Dave. "DeCinces for Robinson". sun-sentinel.com. Retrieved 1 December 2019.

- Baseball Reference Box Score. Retrieved on April 18, 2012.

- John Eisenberg, From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: An Oral History of the Baltimore Orioles, pages 335-36 (2001). Retrieved on April 18, 2012.

- Id. at 336.

- Audio of the Orioles' radio network broadcast of Doug DeCinces's game-winning home run on June 22, 1979 on YouTube. Retrieved on May 11, 2013.

- Chass, Murray. "Orioles Conquer Angels, 9–8," The New York Times, Friday, October 5, 1979. Retrieved October 31, 2020

- Palmer, Jim; Dale, Jim (1996). Palmer and Weaver: Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel. pp. 139–41. ISBN 0-8362-0781-5.

- Wilson, Doug (2014). Brooks: The Biography of Brooks Robinson. New York: Thomas Dunne Books. p. 247. ISBN 978-1250033048.

- Boswell, Thomas. "Orioles Give Up DeCinces for Ford," The Washington Post, Friday, January 29, 1982. Retrieved October 31, 2020

- "Ford Approves Trade From Angels to Orioles," The Associated Press (AP), Sunday, January 31, 1982. Retrieved October 31, 2020

- Mike Penner, Latest Bout with Back Problems Forces DeCinces' Retirement from Baseball, Los Angeles Times (November 2, 1988). Retrieved on April 30, 2013.

- "SEC Charges Former Professional Baseball Player Doug DeCinces and Three Others with Insider Trading". Securities and Exchange Commission. Archived from the original on 6 August 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2011.

- Id. See also Stuart Pfeifer, Ex-Angels player Doug DeCinces settles insider trading lawsuit, Los Angeles Times (August 5, 2011). Retrieved on April 18, 2012.

- "Former MLB All-Star Doug DeCinces indicted for insider trading". USA Today. November 28, 2012.

- Hannah Fry, Former Angels player Doug DeCinces found guilty of insider trading, Los Angeles Times (May 12, 2017). Retrieved on May 13, 2017.

- "Former Oriole Doug DeCinces Convicted For Insider Trading", WJZ-TV Baltimore (May 13, 2017). Retrieved on August 14, 2019.

- Emery, Sean. "Judge dismisses criminal case against man convicted of insider trading alongside ex-Angel star Doug DeCinces", Orange County Register (April 16, 2019). Retrieved on August 14, 2019.

- "Former Angels player Doug DeCinces gets home detention in insider trading case". LA Times. August 13, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- "DeCinces gets home detention". Baltimore Sun. August 14, 2019. p. Sports 4.

External links

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet, or Baseball Reference Bullpen, or SABR BioProject, or Pelota Binaria (Venezuelan Winter League)