Downton Abbey

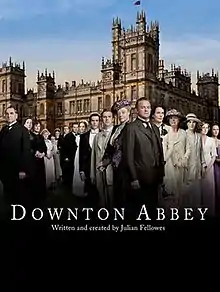

Downton Abbey is a British historical drama television series set in the early 20th century, created and co-written by Julian Fellowes. The series first aired on ITV in the United Kingdom on 26 September 2010, and in the United States on PBS, which supported production of the series as part of its Masterpiece Classic anthology, on 9 January 2011.

The series, set in the fictional Yorkshire country estate of Downton Abbey between 1912 and 1926, depicts the lives of the aristocratic Crawley family and their domestic servants in the post-Edwardian era—with the great events of the time having an effect on their lives and on the British social hierarchy. Events depicted throughout the series include news of the sinking of the Titanic in the first series; the outbreak of the First World War, the Spanish influenza pandemic, and the Marconi scandal in the second series; the Irish War of Independence leading to the formation of the Irish Free State in the third series; the Teapot Dome scandal in the fourth series; the British general election of 1923 and the Beer Hall Putsch in the fifth series. The sixth and final series introduces the rise of the working class during the interwar period and hints at the eventual decline of the British aristocracy.

Downton Abbey has received acclaim from television critics and won numerous accolades, including a Golden Globe Award for Best Miniseries or Television Film and a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Miniseries or Movie. It was recognised by Guinness World Records as the most critically acclaimed English-language television series of 2011. It earned the most nominations of any international television series in the history of the Primetime Emmy Awards, with twenty-seven in total (after the first two series). It was the most watched television series on both ITV and PBS, and subsequently became the most successful British costume drama series since the 1981 television serial of Brideshead Revisited.[1]

On 26 March 2015, Carnival Films and ITV announced that the sixth series would be the last. It aired on ITV between 20 September 2015 and 8 November 2015. The final episode, serving as the annual Christmas special, was broadcast on 25 December 2015. A film adaptation, serving as a continuation of the series, was confirmed on 13 July 2018 and subsequently released in the United Kingdom on 13 September 2019, and in the United States on 20 September 2019.

Plot overview

| Series | Episodes | Originally aired | Avg. UK viewers (millions)[2] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First aired | Last aired | |||||

| 1 | 7 | 26 September 2010 | 7 November 2010 | 9.70 | ||

| 2 | 8 (+1) | 18 September 2011 | 6 November 2011 25 December 2011 (special) | 11.68 | ||

| 3 | 8 (+1) | 16 September 2012 | 4 November 2012 25 December 2012 (special) | 11.91 | ||

| 4 | 8 (+1) | 22 September 2013 | 10 November 2013 25 December 2013 (special) | 11.84 | ||

| 5 | 8 (+1) | 21 September 2014 | 9 November 2014 25 December 2014 (special) | 10.40 | ||

| 6 | 8 (+1) | 20 September 2015 | 8 November 2015 25 December 2015 (special) | 10.42 | ||

| Film | 13 September 2019[3] | N/A | ||||

Series 1: 2010

The first series, comprising seven episodes, explores the lives of the fictional Crawley family, the hereditary Earls of Grantham, and their domestic servants. The storyline centres on the fee tail or "entail" governing the titled elite, which endows title and estate exclusively to male heirs. As part of the backstory, the main character, Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham, had resolved his father's past financial difficulties by marrying Cora Levinson, an American heiress. Her considerable dowry is now contractually incorporated into the commital entail in perpetuity; however, Robert and Cora have three daughters and no son.

As the eldest daughter, Lady Mary Crawley had agreed to marry her second cousin Patrick, the son of the then-heir presumptive James Crawley. The series begins the day after the sinking of the RMS Titanic on 14/15 April 1912. The first episode starts as news reaches Downton Abbey that both James and Patrick have perished in the sinking of the ocean liner. Soon it is discovered that a more distant male cousin, solicitor Matthew Crawley, the son of an upper-middle-class doctor, has become the next heir presumptive. The story initially centres on the relationship between Lady Mary and Matthew, who resists embracing an aristocratic lifestyle, while Lady Mary resists her own attraction to the handsome new heir presumptive.

Of several subplots, one involves John Bates, Lord Grantham's new valet and former Boer War batman, and Thomas Barrow, an ambitious young footman, who resents Bates for taking over the position he had desired. Bates and Thomas remain at odds as Barrow works to sabotage Bates' every move. After learning Bates had recently been released from prison, Thomas and Miss O'Brien (Lady Grantham's Lady's maid) begin a relentless pursuit that nearly ruins the Crawley family in scandal. Barrow — a homosexual man in late Edwardian England – and O'Brien create havoc for most of the staff and family. When Barrow is caught stealing, he hands in his notice to join the Royal Army Medical Corps. Matthew eventually does propose to Lady Mary, but she puts him off when Lady Grantham becomes pregnant, understanding that Matthew would no longer be heir if the baby is a boy. Cora loses the baby after O'Brien, believing she is soon to be fired, retaliates by leaving a bar of soap on the floor next to the bathtub, causing Cora to slip while getting out of the tub, and the fall resulting in a miscarriage. Although Lady Mary intends to accept Matthew, Matthew believes her reticence is due to the earlier uncertainty of his heirship and emotionally rescinds his proposal, leaving Lady Mary devastated. The series ends just after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

Series 2: 2011

.jpg.webp)

The second series comprises eight episodes and runs from the Battle of the Somme in 1916 to the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. During the war, Downton Abbey is temporarily converted into an officers' convalescent hospital.

Matthew, having left Downton, is now a British Army officer and has become engaged. His fiancée is Lavinia Swire, the daughter of a Liberal minister. William Mason, the 2nd footman, is drafted, even after attempts by the Dowager Countess of Grantham to save him from conscription. William is taken under Matthew's protection as his personal orderly. Both are injured in a bomb blast. William dies from his wounds, but only after a deathbed marriage to Daisy, the kitchen maid. While Daisy does not believe she loves William, she marries him in last days as his dying wish. It is not until a brief encounter with the Dowager Countess that she begins to realise that her love was real, but was unable to admit it herself at the time.

Mary, while acknowledging her feelings for Matthew, becomes engaged to Sir Richard Carlisle, a powerful and ruthless newspaper mogul. Their relationship is rocky, but Mary feels bound to Carlisle after he agrees to kill a story regarding her past scandalous indiscretion. Bates's wife, Vera, repeatedly causes trouble for John and Anna, who is now his fiancée, and threatens to expose Mary's indiscretion. When Mrs Bates mysteriously commits suicide with an arsenic pie, leaving no note, Bates is arrested on suspicion of her murder. Matthew and Mary realise they are still in love, but Matthew remains staunchly committed to Lavinia in order to keep his word and promise to marry her regardless of his own spinal injury from the blast. Unknown to them both, Lavinia, ill with Spanish flu, sees and overhears Matthew and Mary admit their love for one another while dancing to a song playing on the phonograph gifted as a wedding present to Matthew and Lavinia. The Spanish influenza epidemic hits Downton Abbey further with Cora, taken seriously ill, as well as Carson, the butler. During the outbreak, Thomas attempts to make up for his inability to find other employment after the war by making himself as useful as possible and is made Lord Grantham's valet after Bates is arrested. Lavinia dies abruptly, which causes great guilt to both Matthew and Mary. Bates is found guilty of murder and sentenced to death but the sentence is commuted to life in prison. After a talk with Robert, Mary realises that she must break off her engagement to Carlisle; a fight breaks out, but in the end Carlisle goes quietly and is never heard from again. The annual Servants' Ball is held at Downton, and Mary and Matthew finally find their way to a marriage proposal on a snowy evening outside the Abbey.

Lady Sybil, the youngest Crawley daughter, begins to find her aristocratic life stifling, falls in love with Tom Branson, the new chauffeur of Irish descent with strong socialist leanings. She is talked out of elopement by her sisters and eventually receives Lord Grantham's reluctant blessing.

Ethel Parks, a new housemaid, is seduced by an injured officer, Major Bryant. Mrs Hughes, the housekeeper, finds them together in bed and dismisses Ethel, but takes pity on her and helps her when Ethel tells her she is pregnant. She has a baby boy and names him Charlie after his father, but Major Bryant refuses to acknowledge his paternity.

Series 3: 2012

In episode one of the third series, covering 1920 to 1921, preparations are underway for Mary and Matthew's wedding. Tom and Sybil Branson arrive from Ireland, where they now live, to attend the wedding. Also arriving to attend the wedding of her granddaughter is Cora's mother, Martha Levinson, from America. Robert (Lord Grantham) learns that the bulk of the family's fortune (including Cora's dowry) has been lost due to his well-intentioned, but bad investment in the Grand Trunk Railway. In the meantime, Edith has fallen hard for Sir Anthony Strallen, whom Robert discourages from marrying Edith due to his age and infirm condition. At Edith's insistence, Robert gives in and welcomes Sir Anthony, but even though he loves her, the latter cannot accept the fact that the Grantham family is not happy with the match, and at the altar announces that he cannot go through with the wedding, devastating Edith. Strallen exits the church quickly and is never heard from again.

Meanwhile, Bates's cellmate tries to plant drugs in his bedding, but Bates is informed by a fellow prisoner allowing him time to find the hidden drug package before a search and hide it. Back at Downton, Mrs Hughes finds out she may have breast cancer, which only some of the household hear about, causing deep concern, but the tumour turns out to be benign. Tom Branson and Lady Sybil, now pregnant, return to Downton after Tom is implicated in the burning of an Irish aristocrat's house. After Matthew's reluctance to accept an inheritance from Lavinia's recently deceased father and then Robert's reluctance to accept that inheritance as a gift, Matthew and Robert reach a compromise in which Matthew accepts that the inheritance will be used as an investment in the estate, giving Matthew an equal say in how it is run. However, as time goes on Robert repeatedly resists Matthew and Tom's efforts to modernize the running of the estate to make it profitable.

Tragedy strikes when Sybil dies from eclampsia shortly after giving birth. Tom, devastated, names his daughter Sybil after his late wife. Bates is released from prison after Anna uncovers evidence clearing him of his wife's murder. Tom becomes the new land agent at the suggestion of Violet, the Dowager Countess. Barrow and O'Brien have a falling out, after which O'Brien leads Barrow to believe that Jimmy, the new footman, is sexually attracted to him. Barrow enters Jimmy's room and kisses him while he is sleeping, which wakes him up shocked, confused, and very angry. In the end, Lord Grantham defuses the situation. The family visits Violet's niece Susan, her husband "Shrimpie", the Marquess of Flintshire; and their daughter Rose, in Scotland, accompanied by Matthew and a very pregnant Mary. The Marquess confides to Robert that his estate is bankrupt and will be sold, making Robert recognise that Downton has been saved through Matthew and Tom's efforts to modernise. Mary returns to Downton with Anna and gives birth to the new heir, but Matthew dies in a car crash while driving home from the hospital after seeing his newborn son.

Series 4: 2013

In series four, covering 1922 to 1923, Cora's lady's maid O'Brien leaves to serve Lady Flintshire in British India. Cora hires Edna Braithwaite, who had previously been fired for her interest in Tom. Eventually the situation blows up, and Edna is replaced by Phyllis Baxter.

Lady Mary deeply mourns Matthew's death. Matthew's newly-found will states Mary is to be his sole heir and thus gives her management over his share of the estate until their son, George, comes of age. With Tom's encouragement, Mary assumes a more active role in running Downton. Two new suitors—Lord Gillingham and Charles Blake—arrive at Downton, though Mary, still grieving, is not interested. Middle daughter Lady Edith, who has begun writing a weekly newspaper column, and Michael Gregson, her editor, fall in love. Due to British law, he is unable to divorce his wife, who is mentally ill and in an asylum. Gregson travels to Germany to seek citizenship there, enabling him to divorce, but is killed by Hitler's Brownshirts during riots. Edith is left pregnant and with the help from her paternal aunt, Lady Rosamund, secretly gives birth to a daughter while abroad. She intends to give her up for adoption in Switzerland and places the baby with adoptive parents, but reclaims her after arranging a new adoptive family on the estate: Mr and Mrs Drewe of Yew Tree Farm take the baby in and raise her as their own.

Anna is raped by Lord Gillingham's valet, Mr Green, which Mr Bates later discovers. Subsequently, Mr Green is killed in a London street accident. A local school teacher, Sarah Bunting, and Tom begin a friendship, though Robert (Lord Grantham) despises her due to her openly vocal anti-aristocracy views. In the final Christmas special, Sampson, a card sharp, steals a letter written by the Prince of Wales to his mistress, Rose's friend Freda Ward, which, if made public, would create a scandal; the entire Crawley family connives to retrieve it, though it is Bates who extracts the letter from Sampson's overcoat, and it is returned to Mrs Ward.

Series 5: 2014

In series five, covering the year 1924, a Russian exile, Prince Kuragin, wishes to renew his past affections for the Dowager Countess (Violet). Violet instead locates his wife in British Hong Kong and reunites the Prince and his estranged wife. Scotland Yard and the local police investigate Green's death. Violet learns that Marigold is Edith's daughter. Meanwhile, Mrs Drewe, not knowing Marigold's true parentage, resents Edith's constant visits. To increase his chances with Mary, Charles Blake plots to reunite Gillingham and his ex-fiancée, Mabel. After Edith inherits Michael Gregson's publishing company, she removes Marigold from the Drewes and relocates to London. Simon Bricker, an art expert interested in one of Downton's paintings, shows his true intentions toward Cora and is thrown out by Robert, causing a temporary rift between the couple.

Mrs Patmore's decision to invest her inheritance in real estate inspires Mr Carson, Downton's butler, to do likewise. He suggests that head housekeeper Mrs Hughes invest with him; she confesses she has no money due to supporting a mentally incapacitated sister. The Crawleys' cousin, Lady Rose, daughter of Lord and Lady Flintshire, becomes engaged to Atticus Aldridge, son of Lord and Lady Sinderby. Lord Sinderby strongly objects to Atticus's marrying outside the Jewish faith. Lord Merton proposes to Isobel Crawley (Matthew's mother). She accepts, but later ends the engagement due to Lord Merton's sons' disparaging comments over her status as a commoner. Lady Flintshire employs underhanded schemes to derail Rose and Atticus's engagement, including announcing to everyone at the wedding that she and her husband are divorcing, intending to cause a scandal to stop Rose's marriage to Atticus; they are married anyway.

When Anna is arrested on suspicion of Green's murder, Bates writes a false confession before fleeing to Ireland. Miss Baxter and Molesley, a footman, are able to prove that Bates was in York at the time of the murder. This new information allows Anna to be released. Cora eventually learns the truth about Marigold, and wants her raised at Downton; Marigold is presented as Edith's ward, but Robert and Tom eventually discern the truth: only Mary is unaware. When a war memorial is unveiled in the town, Robert arranges for a separate plaque to honour the cook Mrs Patmore's late nephew, who was shot for cowardice and excluded from his own village's memorial.

The Crawleys are invited to Brancaster Castle, which Lord and Lady Sinderby have rented for a shooting party. While there, Lady Rose, with help from the Crawleys, defuses a personal near-disaster for Lord Sinderby, earning his gratitude and securing his approval of Rose. A second footman, Andy, is hired on Barrow's recommendation. During the annual Downton Abbey Christmas celebration, Tom Branson announces he is moving to America to work for his cousin, taking daughter Sybil with him. Mr Carson proposes marriage to Mrs Hughes and she accepts.

Series 6: 2015

_2.jpg.webp)

In series six, covering the year 1925, changes are once again afoot at Downton Abbey as the middle class rises and more bankrupted aristocrats are forced to sell off their large estates. Downton must do more to ensure its future survival; reductions in staff are considered, forcing Barrow to look for a job elsewhere. Lady Mary defies a blackmailer, who is thwarted by Lord Grantham. With Branson's departure to Boston, Lady Mary becomes the estate agent. Edith is more hands-on in running her magazine and hires a female editor. Lady Violet and Isobel once again draw battle lines as a government take-over of the local hospital is considered.

Meanwhile, Anna suffers repeated miscarriages. Lady Mary takes her to a specialist, who diagnoses a treatable condition, and she becomes pregnant again. Mr Carson and Mrs Hughes disagree on where to hold their wedding reception, but eventually choose to have it at the schoolhouse, during which Tom Branson reappears with Sybil, having returned to Downton for good. Coyle, who tricked Baxter into stealing a previous employer's jewellery, is convicted after she and other witnesses are persuaded to testify. After Mrs Drewe kidnaps Marigold when Edith is not looking, the Drewes vacate Yew Tree Farm; Daisy convinces Tom Branson to ask Lord Grantham to give her father-in-law, Mr Mason, the tenancy. Andy, a footman, offers to help Mr Mason so he can learn about farming, but Andy is held back by his illiteracy; Mr Barrow offers to teach him to read.

Robert suffers a near-fatal health crisis. Previous episodes alluded to health problems for Robert; his ulcer bursts and he is rushed to the hospital for emergency surgery. The operation is successful, but Mary and Tom must take over Downton's operations. Larry Merton's fiancée, Amelia, encourages Lord Merton and Isobel Crawley to renew their engagement, but Lady Violet rightly becomes suspicious. Violet discovers that Amelia wants Isobel, and not her, to be Lord Merton's caretaker in his old age.[4] Daisy and Mr Molesley score high marks on their academic exams; Molesley's are so exceptional that he is offered a teaching position at the school. Mary breaks off with Henry Talbot, unable to live with the constant fear he could be killed in a car race. Bertie Pelham proposes to Edith, but she hesitates to accept because of Marigold. Lady Violet, upset over Lady Grantham replacing her as hospital president, abruptly departs for a long cruise to restore her equanimity.

Bertie Pelham unexpectedly succeeds his late second cousin as 7th Marquess of Hexham and moves into Brancaster Castle; Edith accepts him. Then Mary spitefully exposes Marigold's parentage, causing Bertie to walk out. Tom confronts Mary over her malicious behaviour and her true feelings for Henry. Despondent, Barrow attempts suicide, and is saved by Baxter, causing Robert and Mr Carson to let Barrow stay at Downton while he recovers and while he searches for new employment. Mary and Henry reunite and are married. Edith returns to Downton for the wedding, reconciling with Mary. Mrs Patmore's new bed and breakfast business is tainted by scandal, but saved when Robert, Cora and Rosamund appear there publicly to support her. Mary arranges a surprise meeting for Edith and Bertie with Bertie proposing again. Edith accepts. Edith tells Bertie's moralistic mother Miranda Pelham about Marigold; she turns against the match, but is won over by Edith's honesty. Barrow finds a position as butler and leaves Downton on good terms, but he is unhappy at his new post.

Lord Merton is diagnosed with terminal pernicious anemia, and Amelia blocks Isobel from seeing him. Goaded by Lady Violet, Isobel pushes into the Merton house, and announces she will take Lord Merton to her house to care for him and to marry him – to his delight. Later, Lord Merton is correctly diagnosed with a non-fatal form of anemia. Robert resents Cora's frequent absences as the hospital president, but encouraged by Lady Rose he comes to admire her ability after watching her chair a hospital meeting. Henry and Tom go into business together selling used cars, while Mary announces her pregnancy. Molesley accepts a permanent teaching position and he and Miss Baxter promise to continue seeing each other. Daisy and Andy finally acknowledge their feelings; Daisy decides to move to the farm with Mr Mason, her father-in-law. Carson develops palsy and must retire. Lord Grantham suggests Barrow return as butler, with Mr Carson in an overseeing role. Edith and Bertie are finally married in the series finale, set on New Year's Eve 1925. Lady Rose and Atticus return for the wedding. Anna goes into labour during the reception, and she and Bates become parents to a healthy son.

Film: 2019

On 13 July 2018, the producers confirmed that a feature-length film would be made,[5] with production commencing mid-2018.[6] The film, which was theatrically released on 13 September 2019 in the United Kingdom, revolves around a visit by King George V and Queen Mary to Downton Abbey in 1927, causing a stir among the Crawleys and servants alike.

King George V and Queen Mary were regular visitors to Yorkshire during the 1920s especially after the marriage of their only daughter Princess Mary to Viscount Lascelles in 1922 and the birth of their first grandchild in 1923. The Royals visited every year to stay with them at their family homes of Goldsborough Hall 1922–1930 and later Harewood House. The Royals would often visit and stay with other Yorkshire estates whilst in the area or en route to their Scottish Estate of Balmoral.

Cast and characters

.jpg.webp)

The main cast of the Crawley family is led by Hugh Bonneville as Robert Crawley, the Earl of Grantham, and Elizabeth McGovern as his wife Cora Crawley, the Countess of Grantham. Their three daughters are depicted by Michelle Dockery as Lady Mary Crawley (Talbot), Laura Carmichael as Lady Edith Crawley (Pelham) and Jessica Brown Findlay as Lady Sybil Crawley (Branson). Maggie Smith is Robert Crawley's mother Violet, Dowager Countess of Grantham. Samantha Bond portrays Lady Rosamund Painswick, Robert's sister who resides in Belgrave Square, London. Dan Stevens portrays Matthew Crawley, the new heir, along with Penelope Wilton as his mother, Isobel Crawley, who are brought to Downton. Allen Leech begins the series as Tom Branson, the chauffeur, but falls in love with Lady Sybil, marries her and later becomes the agent for the estate. David Robb portrays Dr Richard Clarkson, the local town doctor.

Joining the cast in series three is Lily James as the Lady Rose MacClare (Aldridge), a second cousin through Violet's family, who is sent to live with the Crawleys because her parents are serving the empire in India and, later, remains there because of family problems. In series three and four, Shirley MacLaine portrays the mother of Cora Crawley, Martha Levinson. Suitors for Lady Mary's affections during the series include Tom Cullen as Lord Gillingham, Julian Ovenden as Charles Blake, and Matthew Goode as Henry Talbot. Edith's fiancé and eventual husband Bertie Pelham, The 7th Marquess of Hexham, is played by Harry Hadden-Paton.

Downton Abbey's senior household staff are portrayed by Jim Carter as Mr Carson, the butler, and Phyllis Logan as Mrs Hughes, the housekeeper. Tensions rise when Rob James-Collier, portraying Thomas Barrow, a footman and later a valet and under-butler, along with Siobhan Finneran as Miss O'Brien, the lady's maid to the Countess of Grantham (up to series three), plot against Brendan Coyle as Mr Bates, the valet to the Earl of Grantham, and his love interest and eventual wife, Anna (Joanne Froggatt), lady's maid to Lady Mary. Kevin Doyle plays the unlucky Mr Molesley, valet to Matthew Crawley. Thomas Howes portrays William Mason, the second footman.

Other household staff are Rose Leslie as Gwen Dawson, a housemaid studying to be a secretary in series one. Amy Nuttall plays Ethel Parks, a maid, beginning in series two and three. Matt Milne joining the cast as Alfred Nugent, O'Brien's nephew, the awkward new footman for series three and four, and Raquel Cassidy plays Baxter, Cora's new lady's maid, who was hired to replace Edna Braithwaithe, who was sacked. Ed Speleers plays the dashing James (Jimmy) Kent, the second footman, from series three through five. In series five and six Michael C. Fox plays Andy Parker, a replacement footman for Jimmy. In series four, five, and six Andrew Scarborough plays Tim Drewe, a farmer of the estate, who helps Lady Edith conceal a big secret.

The kitchen staff includes Lesley Nicol as Mrs Patmore the cook, Sophie McShera as Daisy, the scullery maid who works her way up to assistant cook and marries William Mason. Cara Theobold portrays Ivy Stuart, a kitchen maid, joining the cast for series three and four.

Crawley family

The series is set in fictional Downton Abbey, a Yorkshire country house, which is the home and seat of the Earl and Countess of Grantham, along with their three daughters and distant family members. Each series follows the lives of the aristocratic Crawley family, their friends, and their servants during the reign of King George V.

Production

Gareth Neame of Carnival Films conceived the idea of an Edwardian-era TV drama set in a country house and approached Fellowes, who had won an Academy Award for Best Writing (Original Screenplay) for Gosford Park. The TV series Downton Abbey – written and created by Fellowes – was originally planned as a spin-off of Gosford Park, but instead was developed as a stand-alone property inspired by the film, set decades earlier.[1] Although Fellowes was reluctant to work on another project resembling Gosford Park, within a few weeks he returned to Neame with an outline of the first series. Influenced by Edith Wharton's The Custom of the Country,[2] Fellowes writes the scripts and his wife Emma is an informal story editor.[3]

Filming locations

- Downton Abbey filming locations

_(cropped_and_squared_up).jpg.webp)

Bampton, Oxfordshire

Bampton, Oxfordshire

(Downton village) St Mary's Church, Bampton

St Mary's Church, Bampton

(St Michael and All Angels, Downton) Bampton Library, Bampton

Bampton Library, Bampton

(Downton Cottage Hospital) Churchgate House (the old rectory), Bampton

Churchgate House (the old rectory), Bampton

(Isobel Crawley's house).jpg.webp)

_uncropped.jpg.webp)

Highclere Castle in north Hampshire is used for exterior shots of Downton Abbey and most of the interior filming.[4][5][6][7] The kitchen, servants' quarters and working areas, and some of the "upstairs" bedrooms were constructed and filmed at Ealing Studios.[8] Bridgewater House in the St James area of London served as the family's London home.

Outdoor scenes are filmed in the village of Bampton in Oxfordshire. Notable locations include St Mary's the Virgin Church and the library, which served as the entrance to the cottage hospital.[9] The old rectory in Bampton is used for exterior shots of Isobel Crawley's house, with interior scenes filmed at Hall Place near Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire.[10]

The Downton Abbey of the title and setting is described as lying in Yorkshire. The towns of Easingwold, Kirkby Malzeard, Kirkbymoorside, Malton, Middlesbrough, Ripon, Richmond, and Thirsk, each mentioned by characters in the series, lie in North Yorkshire, as does the city of York, while Leeds—similarly mentioned—lies in West Yorkshire. Yorkshire media speculated the general location of the fictional Downton Abbey to be somewhere in the triangulated area between the towns of Easingwold, Ripon, and Thirsk.[11]

First World War trench warfare scenes in France were filmed in a specially constructed replica battlefield for period war scenes near the village of Akenham in rural Suffolk.[12]

Many historical locations and aristocratic mansions have been used to film various scenes:

The fictional Haxby Park, the estate Sir Richard Carlisle intends to buy in Series 2, is part of Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire.[13] Byfleet Manor in Surrey is the location for the Dower house, home to Violet, Dowager Countess of Grantham,[14] while West Wycombe Park in Buckinghamshire is used for the interior scenes of Lady Rosamund (Samantha Bond)'s London residence in Belgrave Square.[15] A house in Belgrave Square is used for exterior shots.[16]

Inveraray Castle in Argyll, Scotland, doubled as "Duneagle Castle" in the 2012 Christmas special.[17]

Greys Court near Henley-on-Thames in Oxfordshire was used as the family's secondary property, which they proposed moving into and calling "Downton Place" due to financial difficulties in Series Three. Also in the third series, Bates's prison scenes were filmed at Lincoln Castle in Lincolnshire.

Horsted Keynes railway station in Sussex is used as Downton station.[18] The station is part of the heritage Bluebell Railway. St Pancras station in London doubled for King's Cross station in episode one of series 4, in the scene where Lady Edith Crawley meets her lover Michael Gregson.[19] The restaurant scene where Lady Edith meets Michael Gregson and where they share their kiss is filmed at the Criterion Restaurant in Piccadilly Circus which was originally opened in 1874.[20]

Bridgewater House in the St James area of London served as the family's London home. Outdoor scenes are filmed in the village of Bampton in Oxfordshire. Notable locations include St Mary's the Virgin Church and the library, which served as the entrance to the cottage hospital. The old rectory in Bampton is used for exterior shots of Isobel Crawley's house, with interior scenes filmed at Hall Barn, Hall Place near Beaconsfield in Buckinghamshire, featured as Loxley House, the home of Sir Anthony Strallan.[21]

Parts of series 4 were filmed at The Historic Dockyard Chatham, Kent – The Tarred Yarn Store was used in episode one as a workhouse where Mrs Hughes (Phyllis Logan) visits Mr Grigg (Nicky Henson) and in episode two, streets at The Historic Dockyard Chatham were used for the scenes where Lady Rose MacClare (Lily James) is at the market with James Kent (Ed Speleers) watching her.[22] The production had previously filmed in Kent for series 1 where the opening sequence of a train going through the countryside was filmed at the Kent & East Sussex Railway.[23]

Other filming locations for series 4 include the ballroom of The Savile Club in Mayfair, London.[24]

Scenes for the 2013 Christmas special were filmed at Royal Holloway, University of London near Egham, Surrey, West Wittering beach in West Sussex and Berkshire's Basildon Park near Streatley. Lancaster House in London stood in for Buckingham Palace.[25][26]

Alnwick Castle, in Northumberland, was the filming location used for Brancaster Castle in the 2014 and 2015 Christmas specials, which included filming in Alnwick Castle's State Rooms, as well as on the castle's grounds, and at the nearby semi-ruined Hulne Abbey on the Duke of Northumberland's parklands in Alnwick.[27]

In Series 5 and 6, Kingston Bagpuize House in Oxfordshire was used as the location for Cavenham Park, the home of Lord Merton. In Series 6 (2015) the scenes of motor racing at Brooklands were filmed at the Goodwood Circuit in West Sussex. In 2015, Wayfair.co.uk published a map of 70+ Downton Abbey filming locations.[28]

The 2019 film of Downton Abbey uses many of the television locations such as Highclere Castle and Bampton, as well as exterior shots filmed at Beamish Museum.[29]

Opening

The opening music of Downton Abbey, titled "Did I Make the Most of Loving You?",[30] was composed by John Lunn.[31]

A suite version was released on the soundtrack for the show on 19 September 2011 in the UK and later in the US on 13 December 2011. The soundtrack also included the song performed by singer Mary-Jess Leaverland,[32] with lyrics written by Don Black.[33]

Broadcasts

The rights to broadcast Downton Abbey have been acquired in over 220 countries and territories, and the series is viewed by a global audience of an estimated 120 million people.[34]

United Kingdom

The series first aired on the ITV network in the United Kingdom beginning on 26 September 2010, and received its first Britain-wide broadcast when shown on ITV3 beginning in February 2011.

STV, the ITV franchisee in central and northern Scotland (including the Orkney and Shetland islands), originally opted out of showing Downton Abbey, choosing instead to screen a brand-new six-part series of Taggart, following a long practice of opting out of networked United Kingdom-wide programming on the ITV network.[35] This led to backlash from Scottish viewers, who were frustrated at not being able to watch the programme. Many viewers with satellite or cable television tuned into other regional stations of the ITV network, for example ITV London, with viewing figures showing this is also commonplace for other ITV programmes.[36] STV announced in July 2011 that it would show the first and second series of Downton Abbey as part of its autumn schedule.[37] Scottish cast members Phyllis Logan and Iain Glen were both quoted as being pleased with the decision.[38]

United States

In the United States, Downton Abbey was first broadcast in January 2011 on PBS, as part of the 40th season of Masterpiece.[39] The programme was aired in four 90-minute episodes, controversially requiring PBS to alter the beginning and endpoints of each episode and make other small changes, slightly altering each episode's structure to accommodate fitting the programme precisely into the running-times allotted.[40][lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] PBS also added a host (Laura Linney), who introduced each episode, explaining matters such as "the entail" and "Buccaneers"[lower-alpha 3] for the benefit of US viewers, which was labelled by some American critics as condescending.[40] PBS editing for broadcasts in the United States continued in the subsequent seasons.[41] The fifth began airing in the United States on 4 January 2015.[42][43][44]

Canada

In Canada, VisionTV began airing the programme on 7 September 2011. Canadian audiences could also view the series on PBS. Downton Abbey was aired in French on Ici Radio-Canada Télé.[45]

Australia and New Zealand

In Australia, the first series was broadcast on the Seven Network beginning on 29 May 2011;[46] the second series was broadcast beginning on 20 May 2012;[47] and the third series beginning on 10 February 2013.[48] In New Zealand, Prime began airing the first series on 10 May 2011, the second series on 18 October 2011 and the third series on 18 October 2012.[49]

Reception

Critical response

|

At Metacritic, which assigns a normalised rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the first series received an average score of 91, based on 16 reviews, which indicates "universal acclaim".[57] This result earned the show a Guinness World Record in 2011 for "Highest critical review ratings for a TV show", making Downton Abbey the critically best received TV show in the world.[58] Season 4 of Breaking Bad surpassed Downton Abbey's record later in the year, with a score of 96, making the first series of Downton Abbey the second highest rated show of 2011.[59]

The series has been noted for its relatively sympathetic portrayal of the aristocratic family and the class-based society of early 20th century Britain. This has led to criticism from the political left and praise from the right.[60] James Fenton wrote in The New York Review of Books, "it is noticeable that the aristocrats in the series, even the ones who are supposed to be the most ridiculous, never lapse into the most offensive kind of upper-class drawl one would expect of them. Great care has been taken to keep them pleasant and approachable, even when the things they say are sometimes shown to be class-bound and unfeeling."[61] Jerry Bowyer argued in Forbes that the sympathy for aristocracy is over-stated, and that the show is simply more balanced than most period dramas, which he believes have had a tendency to demonise or ridicule upper class characters. He wrote that Downton Abbey shows "there is no inherent need for good TV to be left of center. Stories sympathetic to virtue, preservation of property and admiration of nobility and of wealth can be told beautifully and to wide audiences."[60]

Downton Abbey has been a commercial success and received general acclaim from critics, although some criticise it as superficial, melodramatic or unrealistic. Others defend these qualities as the reason for the show's appeal. David Kamp wrote in Vanity Fair that "melodrama is an uncool thing to trade in these days, but then, that's precisely why Downton Abbey is so pleasurable. In its clear delineation between the goodies and the baddies, in its regulated dosages of highs and lows, the show is welcome counter-programming to the slow-burning despair and moral ambiguity of most quality drama on television right now."[3] In September 2019, The Guardian, which ranked the show 50th on its list of the 100 best TV shows of the 21st century, stated that the show "was TV drama as comfort blanket: at a time of austerity, Julian Fellowes’s country house epic offered elegantly realised solace in the homilies of the past".[62] Mary McNamara of Los Angeles Times wrote, "Possibly the best series of the year."[63] Jill Serjeant of Reuters wrote, "There's a new darling in U.S. pop culture."[64] The staff of Entertainment Weekly wrote, "It's the biggest PBS phenomenon since Sesame Street."[65] David Hinckley of New York Daily News wrote, "Maintains its magic touch."[66]

James Parker, writing in The Atlantic, said, "Preposterous as history, preposterous as drama, the show succeeds magnificently as bad television. The dialogue spins light-operatically along in the service of multiplying plotlets, not too hard on the ear, although now and again a line lands like a tray of dropped spoons. The acting is superb—it has to be."[67] Ben W. Heineman Jr. compared the series unfavourably to Brideshead Revisited, writing "Downton Abbey is entertainment. Its illustrious predecessor in television mega-success about the English upper class, Brideshead Revisited, is art."[68] He noted the lack of character development in Downton. Writing in The Sunday Times, A. A. Gill said that the show is "everything I despise and despair of on British television: National Trust sentimentality, costumed comfort drama that flogs an embarrassing, demeaning, and bogus vision of the place I live in."[3]

Sam Wollaston of The Guardian said,

It's beautifully made—handsome, artfully crafted and acted. Smith, who plays the formidable and disdainful Dowager Countess, has a lovely way of delivering words, always spaced to perfection. This is going to be a treat if you like a lavish period drama of a Sunday evening.[69]

While rumoured, due to the departure of actor Dan Stevens, the death of Matthew Crawley, in the 2012 Christmas special, drew criticism.[70][71] Fellowes defended the decision stating that they 'didn't really have an option' once Stevens decided to leave.[71] Stevens later said that he had no say in the manner of his character's departure but that he was 'sorry' his character had died on Christmas Day.[72]

The third episode of the fourth series, which aired on 6 October 2013, included a warning at the beginning: "This episode contains violent scenes that some viewers may find upsetting."[73] The episode content, in which Anna Bates was raped, led to more than 200 complaints by viewers to UK television regulator Ofcom,[74] while ITV received 60 complaints directly.[75] On 4 November 2013, Ofcom announced it would not be taking action over the controversy citing the warning given, that the episode was screened after 9 pm, and, that the rape took place 'off-screen'.[76] Series 4 also introduced a recurring character, black jazz musician Jack Ross, who had a brief romantic affair with Lady Rose. The casting of Gary Carr drew critical accusations of political correctness in the media. The character of Ross was partially based on Leslie Hutchinson ("Hutch"), a real-life 1920s jazz singer who had an affair with a number of women in high society, among them Edwina Mountbatten.[77][78]

Ratings

The first episode of Downton Abbey had a consolidated British audience of 9.2 million viewers, a 32% audience share—making it the most successful new drama on any channel since Whitechapel was launched on ITV in February 2009. The total audience for the first episode, including repeats and ITV Player viewings, exceeded 11.6 million viewers. This was beaten by the next episode, with a total audience of 11.8 million viewers—including repeats and ITV Player views. Downton Abbey broke the record for a single episode viewing on ITV Player.[79]

The second series premiered in Britain on 18 September 2011 in the same 9 pm slot as the first series, with the first episode attracting an average audience of 9 million viewers on ITV1, a 34.6% share.[80] The second episode attracted a similar following with an average of 9.3 million viewers. In January 2012, the PBS premiere attracted 4.2 million viewers, over double the network's average primetime audience of 2 million. The premiere audience was 18% higher than the first series premiere.[81]

The second series of Downton Abbey gave PBS its highest ratings since 2009. The second series averaged 5.4 million viewers, excluding station replays, DVR viewings and online streaming. The 5.4 million average improved on PBS first series numbers by 25%. Additionally, episodes of series two have been viewed 4.8 million times on PBS's digital portal, which bests series one's online viewing numbers by more than 400 percent. Overall, Downton Abbey-related content has racked up more than 9 million streams across all platforms, with 1.5 million unique visitors, since series 2's 8 January premiere.[82] In 2013, Downton Abbey was ranked the 43rd most well-written TV show of all time by the Writers' Guild of America.[83]

The third series premiered in the UK on 16 September 2012 with an average of 9 million viewers (or a 36% audience share).[84]

For the first time in the UK, episode three received an average of more than 10 million viewers (or a 38.2% audience share).[85] Premiering in the US in January 2013, the third series had an average audience of 11.5 million viewers and the finale on 17 February 2013, drew 12.3 million viewers making it the night's highest rating show.[86] Overall, during its seven-week run, the series had an audience of 24 million viewers making it PBS's highest-rated drama of all time.[86]

The fourth series premiered in the UK on 22 September 2013 with an average audience of 9.5 million viewers—the highest ever for one of the drama's debut episodes.[87] It premiered in the US on 5 January 2014, to an audience of at least 10.2 million viewers, outperforming every other drama on that night; it was the largest audience for PBS since the 1990 premiere of the Ken Burns documentary The Civil War.[88] The second episode attracted an average of 9.6 million UK viewers.[89]

Awards and nominations

Cultural reaction

While Julian Fellowes supports a united Ireland,[90] there has been criticism of the stereotypical Irish characters used in the show, specifically the character of Tom Branson's brother, Kieran, portrayed as a rude and boorish drunk.[91] Allen Leech, who plays Tom Branson defended the series stating that the show did not portray Irish characters in a pejorative fashion.[91] Branson's character took some criticism in Ireland from The Irish Times, which described the character as "an Irish republican turned Downtonian toff".[92]

The character of the Earl of Grantham occasionally expresses negative Catholic views and is described, by The Washington Post, as "xenophobic" but "at least historically accurate".[93] Fellowes, himself a Roman Catholic, explained that he chose to address this in terms of "that casual, almost unconscious anti-Catholicism that was found among the upper classes, which lasted well into my growing up years", adding that he "thought it might be interesting" to explore this in the series and described his own experiences where the aristocracy "were happy for you to come to their dances or shoot their pheasants, but there were plenty who did not want you to marry their daughters and risk Catholic grandchildren".[94]

Authenticity

Fellowes has said he tries to be as authentic in his depiction of the period as he can.[3] Despite this, the show features many linguistic anachronisms.[95] The accents of characters have also been questioned, with the Received Pronunciation of the actors who play the wealthy characters described as "slightly more contemporary" than would be expected among early-20th-century aristocrats; however, this "elicited more natural and unaffected performances from the cast".[96]

In 2010, Fellowes hired Alastair Bruce, an expert on state and court ritual, as historical adviser.[97] Bruce explains his role as being "here to guide the production and particularly the director as they bring Julian's words to life. That also involves getting the social conduct right, and giving actors a sense of surety in the way they deliver a performance."[97] Actor Jim Carter, who plays butler Carson, describes Bruce as the series "etiquette watchdog",[97] and the UK's Daily Telegraph finished its 2011 profile of Bruce's role stating "Downton's authenticity, it seems, is in safe hands."[98] However, historian Simon Schama criticised the show for historical inaccuracies and "pandering to clichés".[99] Producer Gareth Neame defended the show, saying, "Downton is a fictional drama. It is not a history programme, but a drama of social satire about a time when relationships, behaviour and hierarchy were very different from those we enjoy today."[100]

A "tremendous amount of research" went into recreating the servants' quarters at Ealing Studios because Highclere Castle, where many of the upstairs scenes are filmed,[101] was not adequate for representing the "downstairs" life at the fictional manor house.[102] Researchers visited nearly 40 English country houses to help inform what the kitchen should look like, and production designer Donal Woods said of the kitchen equipment that "probably about 60 to 70 per cent of the stuff in there is from that period".[101] Mrs Beeton's Book of Household Management is an important guide to the food served in the series, but Highclere owner, and author of Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey: The Lost Legacy of Highclere Castle, Lady Carnarvon, states that dinner parties in the era "would have been even more over the top" than those shown.[101] Lady Pamela Hicks agreed, stating that "it is ridiculous to think that a weekend party would consist of only fourteen house guests, it would have consisted of at least 40!"[103] However, Carnavon understood the compromises that must be made for television, and adds, "It’s a fun costume drama. It’s not a social documentary. Because it’s so popular, I think some people take it as historical fact."[101]

Home media

Streaming

Previously available on Netflix, since 2013 the series has been available on Amazon Video. It is also available on the PBS app and PBS.org with a PBS Passport subscription.[104][105]

Blu-ray and DVD

On 16 September 2011, two days before the UK premiere of the second series, it was reported by Amazon.com that the first series of Downton Abbey had become the highest selling DVD boxset of all time on the online retailer's website, surpassing popular American programmes such as The Sopranos, Friends and The Wire.[106]

Soundtracks

A soundtrack, featuring music from the series and also new songs, was released by Decca in September 2011. Music by John Lunn and Don Black features, with vocals from Mary-Jess Leaverland and Alfie Boe.[107] A second soundtrack was released on 19 November 2012 entitled Downton Abbey: The Essential Collection[108] and a third and final soundtrack, containing two discs, was released on 15 January 2016 entitled Downton Abbey: The Ultimate Collection and featured music spanning from all six seasons of the series including some from the first soundtrack.[109]

Track listings

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Downton Abbey: The Suite" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 7:09 |

| 2. | "Love and the Hunter" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:18 |

| 3. | "Emancipation" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:15 |

| 4. | "Story of My Life" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:58 |

| 5. | "Fashion" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:19 |

| 6. | "Damaged" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 5:25 |

| 7. | "If You Were the Only Girl in the World" | Alfie Boe | 3:47 |

| 8. | "Preparation" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:27 |

| 9. | "Such Good Luck" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:30 |

| 10. | "Us and Them" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:53 |

| 11. | "Violet" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:56 |

| 12. | "A Drive" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:04 |

| 13. | "An Ideal Marriage" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:43 |

| 14. | "Roses of Picardy" | Alfie Boe | 3:55 |

| 15. | "Telegram" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:45 |

| 16. | "Deception" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:51 |

| 17. | "Titanic" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:10 |

| 18. | "A Song and a Dance" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:30 |

| 19. | "Did I Make the Most of Loving You?" (a shortened version of "Downton Abbey: The Suite" with lyrics) | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Mary-Jess Leaverland | 4:18 |

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Downton Abbey: The Suite" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 7:09 |

| 2. | "Love and the Hunter" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:18 |

| 3. | "Emancipation" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:15 |

| 4. | "Story of My Life" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:58 |

| 5. | "Did I Make the Most of Loving You?" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Mary-Jess Leaverland | 4:18 |

| 6. | "Nothing To Forgive" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:34 |

| 7. | "Fashion" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:19 |

| 8. | "Damaged" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 5:24 |

| 9. | "New World" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:51 |

| 10. | "I'll Count The Days" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Rebecca Ferguson | 2:41 |

| 11. | "The Fallen" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:01 |

| 12. | "A Glimpse of Happiness" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:03 |

| 13. | "Elopement" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 4:44 |

| 14. | "Preparation" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:26 |

| 15. | "Us and Them" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:53 |

| 16. | "Patrick" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:52 |

| 17. | "Deception" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:51 |

| 18. | "A Dangerous Path" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:13 |

| 19. | "With Or Without You" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London, Scala & Kolacny Brothers | 4:34 |

| 20. | "Violet" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:56 |

| 21. | "An Ideal Marriage" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:45 |

| 22. | "A Song and a Dance" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:28 |

| 23. | "Every Breath You Take" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London, Scala & Kolacny Brothers | 4:27 |

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Downton Abbey: The Suite" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 7:09 |

| 2. | "Story of My Life" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:58 |

| 3. | "Love and the Hunter" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:17 |

| 4. | "Preparation" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:27 |

| 5. | "Such Good Luck" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:52 |

| 6. | "Did I Make the Most of Loving You?" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Mary-Jess Leaverland | 4:17 |

| 7. | "Damaged" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 5:25 |

| 8. | "Violet" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:56 |

| 9. | "I'll Count The Days" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Eurielle | 2:42 |

| 10. | "Fashion" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:20 |

| 11. | "Us and Them" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:53 |

| 12. | "The Fallen" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:00 |

| 13. | "Elopement" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 4:44 |

| 14. | "New World" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:51 |

| 15. | "A Dangerous Path" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:12 |

| 16. | "Escapades 1" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 6:04 |

| 17. | "A Glimpse of Happiness" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:03 |

| No. | Title | Artist | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "A Grand Adventure" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 3:24 |

| 2. | "Duneagle" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:06 |

| 3. | "Not One's Just Desserts" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:53 |

| 4. | "Life After Death" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 6:16 |

| 5. | "Marmalade Cake Walk" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 0:56 |

| 6. | "A Mother's Love" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:46 |

| 7. | "The Hunt" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:10 |

| 8. | "Nothing Will Be Easy" | John Lunn, Chamber Orchestra of London & Eurielle | 4:20 |

| 9. | "Down In China Townton" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 1:36 |

| 10. | "Escapades 2" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 5:35 |

| 11. | "Brancaster" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 4:22 |

| 12. | "Goodbye" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:36 |

| 13. | "It's Not Goodbye It's Au Revoir" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:24 |

| 14. | "The New Gladiators" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 4:03 |

| 15. | "Modern Love" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:51 |

| 16. | "Ambassador Stomp" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:10 |

| 17. | "The Butler And The Housekeeper" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:08 |

| 18. | "Two Sisters" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 2:38 |

| 19. | "End Of An Era" | John Lunn & Chamber Orchestra of London | 0:52 |

Cultural impact

Some of the fashion items worn by characters on the show have seen a strong revival of interest in the UK and elsewhere during the show's run, including starched collars, midi skirts, beaded gowns, and hunting plaids.[110]

The Equality (Titles) Bill was an unsuccessful piece of legislation introduced in the UK Parliament in 2013 that would have allowed equal succession of female heirs to hereditary titles and peerages. It was nicknamed the "Downton Abbey law" because it addressed the same issue that affects Lady Mary Crawley, who cannot inherit the estate because it must pass to a male heir.

The decor used on Downton Abbey inspired US Representative Aaron Schock to redecorate his congressional offices in a more luxurious style.[111][112][113] He repaid the $40,000 cost of redecoration following scrutiny of his expenses and questions about his use of public money for personal benefit,[114] and subsequently resigned in March 2015.[115]

In popular culture

- Family Guy, "Chap Stewie": Stewie's wish that he had never been born transports him back in time to a Downton Abbey-like household.

- Iron Man 3: Happy Hogan is a fan of Downton Abbey.[116]

- NCIS, "Return to Sender": McGee references Downton Abbey as he talks to DiNozzo about the difficulty he is having finding an apartment.[117]

Other media

The World of Downton Abbey, a book featuring a behind-the-scenes look at Downton Abbey and the era in which it is set, was released on 15 September 2011. It was written by Jessica Fellowes (the niece of Julian Fellowes) and published by HarperCollins.[107][118]

A second book also written by Jessica Fellowes and published by HarperCollins, The Chronicles of Downton Abbey, was released on 13 September 2012. It is a guide to the show's characters through the early part of the third series.[119]

Due to the show's popularity, there have been a number of references and spoofs on it, such as Family Guy episode "Chap Stewie", which has Stewie Griffin reborn in a household similar to Downton Abbey, and How I Met Your Mother episode "The Fortress", where the gang watch a television show called Woodworthy Manor, which is remarkably similar to Downton Abbey.[120]

The Gilded Age

Julian Fellowes's The Gilded Age is set to debut on HBO, portraying New York in the 1880s and how its old New York society coped with the influx of newly wealthy families.[121][122] While a separate series, a young Violet, Countess of Grantham, could make an appearance on the new show.[123]

Film adaptation

On 13 July 2018, a feature-length film was confirmed,[124] with production to commence mid-2018.[125] The film is written by Julian Fellowes and is a continuation of the TV series, with direction by Brian Percival and will be distributed by Focus Features and Universal Pictures International.[126] The film was released in the United Kingdom on 13 September 2019, with the United States following one week later on 20 September 2019.[127]

See also

Notes

- For example, these structure changes resulted in the character of entail heir Matthew Crawley (played by Dan Stevens) coming into the storyline in the first episode in the United States broadcast, rather than in the second as he had in the UK broadcast.[40]

- The series aired in the UK with commercial breaks, which required PBS, according to a spokeswoman, "to plug those holes".[41]

- American heiresses who married into the British aristocracy during the Gilded Age—see: The Buccaneers, a novel by Edith Wharton.

References

- PBS, "Downton Abbey Revisited", TV documentary special to precede season 3

- Fellowes, Julian (20 February 2013). "Julian Fellowes: 'Abbey' owes much to Wharton". Berkshireeagle.com. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Kamp, David. "The Most Happy Fellowes". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 9 November 2012.

- "Highclere Castle: Downton Abbey". Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Dickson, Elizabeth (January–February 1979). "Historic Houses: the Splendors of Highclere Castle". The Architectural Digest. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Brennan, Morgan (2 May 2013). "Inside Highclere Castle: the Real Life Locale of Downton Abbey". Forbes. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Downton opens for charity". ITV. 21 August 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- Gritten, David (20 September 2010). "Downton Abbey: behind the scenes". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Ffrench, Andrew (23 April 2010). "Village is the star of the show". Oxford Mail. Retrieved 6 October 2011.

- "Enthralled by Crawley House". blogspot.co.uk. 4 February 2013. Archived from the original on 2 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Dobrzynski, Judith H. (15 October 2010). "So where is Downton Abbey?". The Press. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 March 2013.

- Hollingshead, Iain (24 August 2011). "Trench war comes to Downton Abbey". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Waddesdon Manor making space for young minds". The Bucks Herald. 27 January 2014. Archived from the original on 29 January 2016. Retrieved 23 January 2016.

- Morris, Jennifer (13 September 2013). "Downton Abbey home from home for Dame Maggie". Get Surrey. Archived from the original on 12 December 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "National Trust: West Wycombe Park". Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Location Library: London Mansions". Location Works. Archived from the original on 30 May 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Tweedie, Katrina (4 March 2013). "Inveraray Castle Set for Tourism Boost". The Daily Record. Scotland. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Bluebell Railway Station: Horsted Keynes". Bluebell Railway. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "What's Filmed Where". Network Rail. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- Midgley, Neil (13 August 2013). "Downton Abbey, series four, episode one, first look review". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Trips and Tips — Britain on Location". Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Downton Abbey Film Focus". Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- "Kent Film Office Downton Abbey series 1 Article". Kent Film Office. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- Rowley, Emma (13 September 2013). "What Next for Downton Abbey?". The Daily Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "That's A Wrap: Filming on Downton Abbey Season 4 Completed". Downton Abbey Addicts. 17 August 2013. Retrieved 14 November 2013.

- "Downton Abbey heads to Buckingham Palace for Christmas special". Digital Spy. 4 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- "Downton Abbey Exhibition". Alnwick Castle. Archived from the original on 29 September 2015. Retrieved 8 August 2015.

- "Map of Downton Abbey filming locations". Wayfair.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 8 December 2015.

- "New Downton Abbey Film at Beamish Museum". Beamish. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Gold, Brett (18 February 2013). "Downton Abbey Season 3 Finale: A Tragic Twist for Matthew Crawley". RR.com. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc. Archived from the original on 17 October 2013. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- Barry, Maggie (16 September 2012). "Downton Abbey's composer John Lunn reveals James Brown is inspiration behind TV drama's music". Daily Record. Retrieved 8 April 2013.

- O'Brien, Jon (20 September 2011). "Downton Abbey – Various Artists". AllMusic. All Media Network, LLC. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "Digital sheet music – Did I Make the Most of Loving You [sic] – From Downton Abbey". Musicnotes.com. Sony/ATV Music Publishing. 13 February 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- "ITV commissions a fifth series of Downton Abbey | presscentre". ITV. 10 November 2013. Retrieved 24 June 2015.

- "STV's Opting-out Policy Again Comes in for Criticism". allmediascotland. 30 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "Viewers opt out of STV on satellite". BBC News. 31 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- "STV to show Downton Abbey in Autumn schedule". Glasgow: STV. 21 July 2011. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "STV decides to show 'Downton Abbey'". BBC News. 21 July 2011. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 31 October 2011.

- Weisman, John (4 August 2010). "PBS to offer multiplatform content". Variety. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Jace (3 January 2011). "In Defense of Downton Abbey (Or, Don't Believe Everything You Read)". Televisionary. Archived from the original on 6 January 2011. Retrieved 27 March 2016.

- Thomas, June. "Why Downton Abbey Airs So Much Later in the U.S." Slate. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 9 March 2015.

- "Downton Abbey's Season-Five Premiere to Feature Surprising Stunt". Vanity Fair. 20 August 2014. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "Downton Abbey". Geek Town. 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- "MASTERPIECE, Downton Abbey, Series 5". PBS.org. The Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- "Fall 2011 on VisionTV". Channel Canada. 10 August 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- Fox, Tiffany (27 May 2011). "Downton Abbey, Sunday, 8.30 pm, Seven/GWN7". The West Australian. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Downton Abbey, Sunday, May 20". The Sydney Morning Herald. 20 May 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Downton Abbey love tangle revealed". The Sydney Morning Herald. 6 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Korsunsky, Boris (2019). "Downton Abbey". The Physics Teacher (in Polish). TVN Style. 57 (3): 200. Bibcode:2019PhTea..57..200K. doi:10.1119/1.5092489. Archived from the original on 5 October 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Downton Abbey – TV3". Dublin: TV 3. Archived from the original on 7 November 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 1". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 2". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 3". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 4". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 5". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- "Downton Abbey: Season 6". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 5 January 2016.

- "Downton Abbey – Season 1". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2011.

- "Downton Abbey Wins Guinness World Record". Broadcast Now. Broadcast. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 September 2011.

- "Metacritic Ranks for 2011". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2013.

- Bowyer, Jerry (14 February 2013). "Down on Downton: Why The Left Is Torching Downton Abbey". Forbes. Archived from the original on 18 February 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Fenton, James (8 March 2012). "The Abbey That Jumped the Shark". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- "The 100 best TV shows of the 21st century". The Guardian. 16 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019.

- McNamara, Mary (8 January 2011). "From the Archives: The Times' original review of 'Downton Abbey' found 'plenty of sex and secrets, romance and treachery to go 'round'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Serjeant, Jill (8 February 2012). ""Downton Abbey" brings cool TV crowd to America's PBS". Reuters. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- EW Staff (30 December 2013). "This Week's Cover: 'Downton Abbey' keeps our Winter TV Preview classy". EW.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Hinckley, David (4 January 2015). "As 'Downton Abbey' heads into season five, it maintains its magic touch". nydailynews.com. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Parker, James (2 January 2013). "Brideshead Regurgitated". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Heineman Jr., Ben W. (1 February 2013). "'Downton Abbey' Is Entertainment, but 'Brideshead Revisited' Was Art". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- "TV review: Downton Abbey and All New Celebrity Total Wipeout". The Guardian. 27 September 2010. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Groskop, Viv (26 December 2012). "Downton Abbey: plot moving slowly? It must be time for someone to die". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Furness, Hannah (28 December 2012). "Julian Fellowes: 'No option' but to kill off Downton's Matthew". The Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Noah, Sherna (4 June 2013). "Dan Stevens: Killing off Downton Abbey's Matthew on Christmas Day was not my doing". The Independent. London, UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Groskop, Viv (6 October 2013). "Downton Abbey recap: season four, episode three". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Halliday, Josh (9 October 2013). "Downton Abbey rape scene defended by series creator Julian Fellowes". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Sweeney, Sabrina. "Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes defends storyline". BBC. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Downton Abbey to face no action from Ofcom over rape storyline". BBC. 4 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- Grant, Sonia (23 September 2013). "Downton Abbey in Black and White". HuffPost UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Wilson, Christopher (14 October 2013). "The scandalous truth about Downton Abbey's royal gigolo 'Jack Ross'". Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Downton Abbey show gets second series". BBC News. 12 October 2010. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 16 October 2010.

- Plunkett, John (18 September 2011). "Downton Abbey scares Spooks with 9m viewers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- Starr, Michael (10 January 2012). "'Downton Abbey' season 2 premiere averages 4.2 million viewers". New York Post. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- Kenneally, Tim (23 February 2012). "Ratings: 'Downton Abbey' Season 2 Finale Gives PBS Best Numbers Since 2009". Reuters. Retrieved 28 October 2012.

- "101 Best Written TV Series List". Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Deans, Jason (17 September 2012). "Downton Abbey and The X Factor lift ITV's spirits". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Deans, Jason (1 October 2012). "Downton Abbey and The X Factor hit series highs". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "National Ratings Cement "Downton Abbey, Season 3" on MASTERPIECE CLASSIC as Highest-Rated Drama in PBS History". Public Broadcasting Service. 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Szalai, Georg (23 September 2013). "'Downton Abbey' Draws Best Ever U.K. Season Premiere Ratings". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- Stelter, Brian (7 January 2014). "Downton Abbey premiere breaks ratings record". CNN. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2014.

- Plunkett, John (30 September 2013). "Downton Abbey continues strong start". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- "Downton Abbey creator Julian Fellowes: I support a united Ireland". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- Finn, Melanie (3 November 2012). "Downton's not anti-Irish, says star Alan". Herald. Dublin. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2013.

- "If Downton Abbey is going to end on a high, the revolution will need to be bloody". Irish Times. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 12 August 2016.

- Henneberger, Melinda (29 January 2013). "The politics of Downton Abbey: Down with the patriarchy!". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- Walker, Tim (22 October 2012). "Downton Abbey's anti-Catholic plot". The Telegraph. London, UK. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- Haglund, David (9 February 2012). "Did You See This? Downton Abbey Anachronisms". Slate. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- Trawick-Smith, Ben (19 January 2012). "The Accents in Downton Abbey". Dialect Blog. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Gritten, David (20 September 2010). "Downton Abbey: behind the scenes". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Power, Vicki (16 September 2011). "How Downton minds its manners". The Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Schama, Simon (20 January 2016). "No Downers in 'Downton'". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 31 October 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- "Simon Schama brands Downton 'cultural necrophilia'". BBC News. 18 January 2012. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Krystal, Becky (31 December 2012). "On 'Downton Abbey,' aspic matters". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Kennicott, Philip (29 January 2011). "A Victorian fantasy, in stone". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- Hicks, India (29 November 2016). "Watching The Crown with Lady Pamela Hicks, Queen Elizabeth's Lady-in-Waiting". Town and Country. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 27 January 2017.

- "Netflix To End 'Downton Abbey' Streaming As Amazon Snatches Exclusive Rights To Latest Season". deadline.com. 1 February 2013. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- Locker, Melissa (20 September 2019). "How to catch up on 'Downton Abbey': 6 easy recaps before seeing the movie". Fast Company. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 21 September 2019.

- "Downton Abbey becomes top selling DVD box set of all time". Metro. 16 September 2011. Retrieved 21 September 2011.

- "Downton Abbey Series Two Press Pack" (PDF). ITV. July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- "Downton Abbey – The Essential Collection". Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- "Downton Abbey – The Ultimate Collection [2 CD]". Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 18 January 2020.

- Kealey, Helena (31 October 2014). "Downton Abbey: retro fashion revivals". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "Illinois Rep. Aaron Schock under fire for 'Downton Abbey' office redo". Chicagotribune.com. 3 February 2015. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Terris, Ben (18 December 2014). "He's got a 'Downton Abbey'-inspired office, but Rep. Aaron Schock won't talk about it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Miller, Julie (3 February 2015). "33-Year-Old Congressman Aaron Schock Causes Controversy with Downton Abbey-Themed Office". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- "Aaron Schock reimburses US for $40,000 Downton Abbey office remodel". The Guardian. 27 February 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

- "Rep. Aaron Schock announces resignation in wake of spending probe". The Washington Post. 17 March 2015. Archived from the original on 15 November 2020. Retrieved 24 June 2015.