Drainage basin

A drainage basin is any area of land where precipitation collects and drains off into a common outlet, such as into a river, bay, or other body of water. The drainage basin includes all the surface water from rain runoff, snowmelt, hail, sleet and nearby streams that run downslope towards the shared outlet, as well as the groundwater underneath the earth's surface.[1] Drainage basins connect into other drainage basins at lower elevations in a hierarchical pattern, with smaller sub-drainage basins, which in turn drain into another common outlet.[2]

Other terms for drainage basin are catchment area, catchment basin, drainage area, river basin, water basin,[3] [4] and impluvium.[5][6][7] In North America, the term watershed is commonly used to mean a drainage basin, though in other English-speaking countries, it is used only in its original sense, that of a drainage divide.

In a closed drainage basin, or endorheic basin, the water converges to a single point inside the basin, known as a sink, which may be a permanent lake, a dry lake, or a point where surface water is lost underground.[8]

The drainage basin acts as a funnel by collecting all the water within the area covered by the basin and channelling it to a single point. Each drainage basin is separated topographically from adjacent basins by a perimeter, the drainage divide, making up a succession of higher geographical features (such as a ridge, hill or mountains) forming a barrier.

Drainage basins are similar but not identical to hydrologic units, which are drainage areas delineated so as to nest into a multi-level hierarchical drainage system. Hydrologic units are defined to allow multiple inlets, outlets, or sinks. In a strict sense, all drainage basins are hydrologic units but not all hydrologic units are drainage basins.[8]

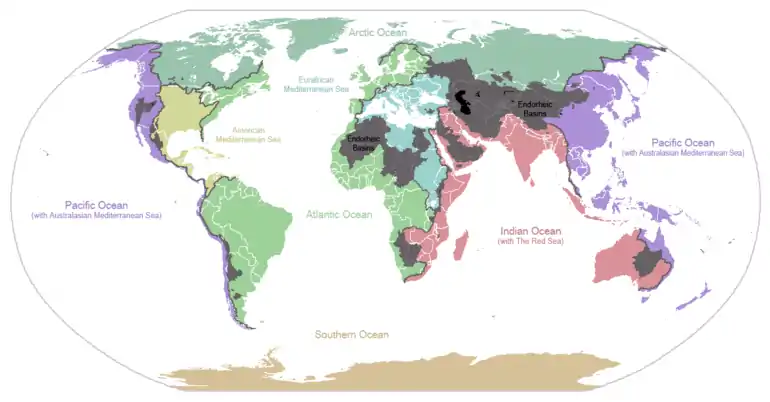

Major drainage basins of the world

Map

Ocean basins

The following is a list of the major ocean basins:

- About 48.7% of the world's land drains to the Atlantic Ocean. In North America, surface water drains to the Atlantic via the Saint Lawrence River and Great Lakes basins, the Eastern Seaboard of the United States, the Canadian Maritimes, and most of Newfoundland and Labrador. Nearly all of South America east of the Andes also drains to the Atlantic, as does most of Western and Central Europe and the greatest portion of western Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as Western Sahara and part of Morocco. The two major mediterranean seas of the world also flow to the Atlantic:

- The Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico basin includes most of the U.S. interior between the Appalachian and Rocky Mountains, a small part of the Canadian provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, eastern Central America, the islands of the Caribbean and the Gulf, and a small part of northern South America.

- The Mediterranean Sea basin includes much of North Africa, east-central Africa (through the Nile River), Southern, Central, and Eastern Europe, Turkey, and the coastal areas of Israel, Lebanon, and Syria.

- The Arctic Ocean drains most of Western and Northern Canada east of the Continental Divide, northern Alaska and parts of North Dakota, South Dakota, Minnesota, and Montana in the United States, the north shore of the Scandinavian peninsula in Europe, central and northern Russia, and parts of Kazakhstan and Mongolia in Asia, which totals to about 17% of the world's land.

- Just over 13% of the land in the world drains to the Pacific Ocean. Its basin includes much of China, eastern and southeastern Russia, Japan, the Korean Peninsula, most of Indochina, Indonesia and Malaysia, the Philippines, all of the Pacific Islands, the northeast coast of Australia, and Canada and the United States west of the Continental Divide (including most of Alaska), as well as western Central America and South America west of the Andes.

- The Indian Ocean's drainage basin also comprises about 13% of Earth's land. It drains the eastern coast of Africa, the coasts of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf, the Indian subcontinent, Burma, and most of Australia.

- The Southern Ocean drains Antarctica. Antarctica comprises approximately eight percent of the Earth's land.

Largest river basins

The five largest river basins (by area), from largest to smallest, are the basins of the Amazon (7M km2), the Congo (4M km2), the Nile (3.4M km2), the Mississippi (3.22M km2), and the Río de la Plata (3.17M km2). The three rivers that drain the most water, from most to least, are the Amazon, Ganga, and Congo rivers.[9]

Endorheic drainage basins

Endorheic drainage basins are inland basins that do not drain to an ocean. Around 18% of all land drains to endorheic lakes or seas or sinks. The largest of these consists of much of the interior of Asia, which drains into the Caspian Sea, the Aral Sea, and numerous smaller lakes. Other endorheic regions include the Great Basin in the United States, much of the Sahara Desert, the drainage basin of the Okavango River (Kalahari Basin), highlands near the African Great Lakes, the interiors of Australia and the Arabian Peninsula, and parts in Mexico and the Andes. Some of these, such as the Great Basin, are not single drainage basins but collections of separate, adjacent closed basins.

In endorheic bodies of standing water where evaporation is the primary means of water loss, the water is typically more saline than the oceans. An extreme example of this is the Dead Sea.

Importance

Geopolitical boundaries

Drainage basins have been historically important for determining territorial boundaries, particularly in regions where trade by water has been important. For example, the English crown gave the Hudson's Bay Company a monopoly on the fur trade in the entire Hudson Bay basin, an area called Rupert's Land. Bioregional political organization today includes agreements of states (e.g., international treaties and, within the US, interstate compacts) or other political entities in a particular drainage basin to manage the body or bodies of water into which it drains. Examples of such interstate compacts are the Great Lakes Commission and the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency.

Hydrology

In hydrology, the drainage basin is a logical unit of focus for studying the movement of water within the hydrological cycle, because the majority of water that discharges from the basin outlet originated as precipitation falling on the basin. A portion of the water that enters the groundwater system beneath the drainage basin may flow towards the outlet of another drainage basin because groundwater flow directions do not always match those of their overlying drainage network. Measurement of the discharge of water from a basin may be made by a stream gauge located at the basin's outlet.

Rain gauge data is used to measure total precipitation over a drainage basin, and there are different ways to interpret that data. If the gauges are many and evenly distributed over an area of uniform precipitation, using the arithmetic mean method will give good results. In the Thiessen polygon method, the drainage basin is divided into polygons with the rain gauge in the middle of each polygon assumed to be representative for the rainfall on the area of land included in its polygon. These polygons are made by drawing lines between gauges, then making perpendicular bisectors of those lines form the polygons. The isohyetal method involves contours of equal precipitation are drawn over the gauges on a map. Calculating the area between these curves and adding up the volume of water is time-consuming.

Isochrone maps can be used to show the time taken for runoff water within a drainage basin to reach a lake, reservoir or outlet, assuming constant and uniform effective rainfall.[10][11][12][13]

Geomorphology

Drainage basins are the principal hydrologic unit considered in fluvial geomorphology. A drainage basin is the source for water and sediment that moves from higher elevation through the river system to lower elevations as they reshape the channel forms.

Ecology

Drainage basins are important in ecology. As water flows over the ground and along rivers it can pick up nutrients, sediment, and pollutants. With the water, they are transported towards the outlet of the basin, and can affect the ecological processes along the way as well as in the receiving water source.

Modern use of artificial fertilizers, containing nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium, has affected the mouths of drainage basins. The minerals are carried by the drainage basin to the mouth, and may accumulate there, disturbing the natural mineral balance. This can cause eutrophication where plant growth is accelerated by the additional material.

Resource management

Because drainage basins are coherent entities in a hydro-logical sense, it has become common to manage water resources on the basis of individual basins. In the U.S. state of Minnesota, governmental entities that perform this function are called "watershed districts". In New Zealand, they are called catchment boards. Comparable community groups based in Ontario, Canada, are called conservation authorities. In North America, this function is referred to as "watershed management". In Brazil, the National Policy of Water Resources, regulated by Act n° 9.433 of 1997, establishes the drainage basin as the territorial division of Brazilian water management.

When a river basin crosses at least one political border, either a border within a nation or an international boundary, it is identified as a transboundary river. Management of such basins becomes the responsibility of the countries sharing it. Nile Basin Initiative, OMVS for Senegal River, Mekong River Commission are a few examples of arrangements involving management of shared river basins.

Management of shared drainage basins is also seen as a way to build lasting peaceful relationships among countries.[14]

Catchment factors

The catchment is the most significant factor determining the amount or likelihood of flooding.

Catchment factors are: topography, shape, size, soil type, and land use (paved or roofed areas). Catchment topography and shape determine the time taken for rain to reach the river, while catchment size, soil type, and development determine the amount of water to reach the river.

Topography

Generally, topography plays a big part in how fast runoff will reach a river. Rain that falls in steep mountainous areas will reach the primary river in the drainage basin faster than flat or lightly sloping areas (e.g., > 1% gradient).

Shape

Shape will contribute to the speed with which the runoff reaches a river. A long thin catchment will take longer to drain than a circular catchment.

Size

Size will help determine the amount of water reaching the river, as the larger the catchment the greater the potential for flooding. It is also determined on the basis of length and width of the drainage basin.

Soil type

Soil type will help determine how much water reaches the river. The runoff from the drainage area is dependent on the soil type.Certain soil types such as sandy soils are very free-draining, and rainfall on sandy soil is likely to be absorbed by the ground. However, soils containing clay can be almost impermeable and therefore rainfall on clay soils will run off and contribute to flood volumes. After prolonged rainfall even free-draining soils can become saturated, meaning that any further rainfall will reach the river rather than being absorbed by the ground. If the surface is impermeable the precipitation will create surface run-off which will lead to higher risk of flooding; if the ground is permeable, the precipitation will infiltrate the soil.

Land use

Land use can contribute to the volume of water reaching the river, in a similar way to clay soils. For example, rainfall on roofs, pavements, and roads will be collected by rivers with almost no absorption into the groundwater.

See also

- Continental Divide of the Americas – principal hydrological divide of North and South America

- Integrated catchment management

- Interbasin transfer

- International Journal of River Basin Management (JRBM)

- International Network of Basin Organizations

- Main stem

- River basin management plans

- River bifurcation

- Tenaja

- Time of concentration

References

Citations

- "drainage basin". The Physical Environment. University of Wisconsin–Stevens Point. Archived from the original on March 21, 2004.

- "What is a watershed and why should I care?". university of delaware. Archived from the original on 2012-01-21. Retrieved 2008-02-11.

- Lambert, David (1998). The Field Guide to Geology. Checkmark Books. pp. 130–13. ISBN 0-8160-3823-6.

- Uereyen, Soner; Kuenzer, Claudia (9 December 2019). "A Review of Earth Observation-Based Analyses for Major River Basins". Remote Sensing. 11 (24): 2951. Bibcode:2019RemS...11.2951U. doi:10.3390/rs11242951.

- Huneau, F.; Jaunat, J.; Kavouri, K.; Plagnes, V.; Rey, F.; Dörfliger, N. (2013-07-18). "Intrinsic vulnerability mapping for small mountainous karst aquifers, implementation of the new PaPRIKa method to Western Pyrenees (France)". Engineering Geology. Elsevier. 161: 81–93. doi:10.1016/j.enggeo.2013.03.028.

Efficient management is strongly correlated to the proper protection perimeter definition around springs and proactive regulation of land uses over the spring's catchment area ("impluvium").

- Lachassagne, Patrick (2019-02-07). "Natural mineral waters". Encyclopédie de l'environnement. Retrieved 2019-06-10.

In order to preserve the long-term stability and purity of natural mineral water, bottlers have put in place "protection policies" for the impluviums (or catchment areas) of their sources. The catchment area is the territory on which the part of precipitated rainwater (and/or snowmelt) that infiltrates the subsoil feeds the mineral aquifer and thus contributes to the renewal of the resource. In other words, a precipitated drop on the impluvium territory may join the mineral aquifer; ...

- Labat, D.; Ababou, R.; Manginb, A. (2000-12-05). "Rainfall–runoff relations for karstic springs. Part I: convolution and spectral analyses". Journal of Hydrology. 238 (3–4): 123–148. Bibcode:2000JHyd..238..123L. doi:10.1016/S0022-1694(00)00321-8.

The non-karstic impluvium comprises all elements of the ground surface and soils that are poorly permeable, on a part of which water is running while also infiltrating on another minor part. This superficial impluvium, if it exists, constitutes the first level of organisation of the drainage system of the karstic basin.

- "Hydrologic Unit Geography". Virginia Department of Conservation & Recreation. Archived from the original on 14 December 2012. Retrieved 21 November 2010.

- Encarta Encyclopedia articles on Amazon River, Congo River, and Ganges Published by Microsoft in computers.

- Bell, V. A.; Moore, R. J. (1998). "A grid-based distributed flood forecasting model for use with weather radar data: Part 1. Formulation" (PDF). Hydrology and Earth System Sciences. Copernicus Publications. 2 (2/3): 265–281. Bibcode:1998HESS....2..265B. doi:10.5194/hess-2-265-1998.

- Subramanya, K (2008). Engineering Hydrology. Tata McGraw-Hill. p. 298. ISBN 978-0-07-064855-5.

- "EN 0705 isochrone map". UNESCO. Archived from the original on November 22, 2012. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- "Isochrone map". Webster's Online Dictionary. Retrieved March 21, 2012.

- "Articles". www.strategicforesight.com.

Sources

- DeBarry, Paul A. (2004). Watersheds: Processes, Assessment and Management. John Wiley & Sons.

External links

- Instructional video: Manual watershed delineation is a five-step process

- Instructional video: To delineate a watershed you must identify land surface features from topographic contours

- Science week catchment factsheet

- Catchment Modelling Toolkit

- Water Evaluation And Planning System (WEAP) - modeling hydrologic processes in a drainage basin

- New Mexico State University - Water Task Force

- Recommended Watershed Terminology

- Watershed Condition Classification Technical Guide United States Forest Service

- Science in Your Watershed, USGS

- Studying Watersheds: A Confluence of Important Ideas

- Water Sustainability Project Sustainable water management through demand management and ecological governance, with the POLIS Project at the University of Victoria

- Map of the Earth's primary watersheds, WRI

- What is a watershed and why should I care?

- Cycleau - A project looking at approaches to managing catchments in North West Europe

- flash animation of how rain falling onto the landscape will drain into a river depending on the terrain

- StarHydro – software tool that covers concepts of fluvial geomorphology and watershed hydrology

- EPA Surf your watershed

- Florida Watersheds and River Basins - Florida DEP