Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg

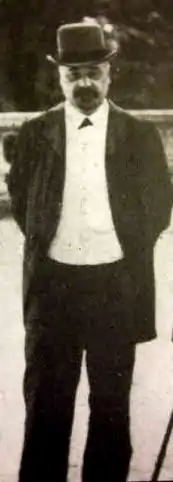

Duke Constantine Frederick Peter of Oldenburg (German: Herzog Konstantin Friedrich Peter von Oldenburg; Russian: Константин Петрович Ольденбургский, tr. Konstantin Petrovich Oldenburgskiy; 9 May 1850 - 18 March 1906) was a son of Duke Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg and his wife Princess Therese of Nassau-Weilburg Known in the court of Tsar Nicholas II as Prince Constantine Petrovich Oldenburgsky, he was the father of the Russian Counts and Countesses von Zarnekau.

| Duke Constantine | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Born | 9 May 1850 St. Petersburg, Russian Empire | ||||

| Died | 18 March 1906 (aged 55) Nice, France | ||||

| Spouse | Agrippina Japaridze, Countess von Zarnekau | ||||

| Issue | Aleksandra Konstantinovna, Princess Yurievsky Countess Ekaterina Konstantinovna von Zarnekau Count Nikolai Konstantinovich von Zarnekau Count Aleksei Konstantinovich von Zarnekau Count Pyotr Konstantinovich von Zarnekau Countess Nina Konstantinovna von Zarnekau | ||||

| |||||

| House | Holstein-Gottorp | ||||

| Father | Duke Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg | ||||

| Mother | Princess Therese of Nassau-Weilburg | ||||

Family

As the seventh-born child in his family, Duke Constantine Petrovich was a junior member of a cadet branch of the House of Holstein-Gottorp, a small ducal house based on Germany's border with Denmark.

During the 18th Century, the Dukes of Holstein-Gottorp gained influence through a carefully planned series of marital alliances with the royal houses of Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Prussia. The childless Empress Elizabeth of Russia proclaimed her nephew, Charles Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp heir to the throne and when he became Tsar Peter III of Russia in 1762, the Holstein-Gottorps, themselves a cadet branch of the House of Oldenburg, became the Imperial house of Russia, which they ruled until 1917 under the name of Romanov.

Tsar Peter III of Russia married on 21 August 1745 to his second cousin, the Prussian princess Sophie Friederike Auguste von Anhalt-Zerbst-Dornburg, better known as Catherine II or Catherine the Great. The couple had one son, Paul, who, after the death of Empress Catherine in 1796, ruled as Emperor Paul I of Russia until his assassination in 1801. Paul and his wife, Maria Feodorovna, Duchess of Württemberg, had 10 children. Their eldest son ruled as Emperor Alexander I of Russia between 1801 and 1825, the period of the Napoleonic Wars.

In 1808, when Oldenburg was overrun by French and Dutch troops, Peter I, the Grand Duke of Oldenburg and Prince-Bishop of Lübeck, sent his second-eldest son, Duke George of Oldenburg, to stay in Russia with his relatives, the Russian Imperial Family.

On 3 August 1809, Duke George of Oldenburg, the grandfather of Duke Constantine Petrovich, married to Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna, daughter of Tsar Paul I. The marriage was arranged hastily, as a means of avoiding a forced marriage with Napoleon Bonaparte, but it turned out to be a happy match. Catherine Pavlovna was a favorite sister of Tsar Alexander I, and Duke George of Oldenburg became a favorite at court.

They had two children. Their second son, Duke Peter Georgievich of Oldenburg, the father of Constantine Petrovich, was born in 1812.

Early life

By the time that Constantine Petrovich was born in 1850, the Russian branch of the Oldenburg family was thriving. Constantine's father, Duke Peter Georgievich, had won respect serving as a Colonel in the Tsar's Semenovsky Life Guards Regiment in the 1820s, had become a Russian senator in 1834, had founded the Imperial School of Jurisprudence in 1835, and had played a leading role in funding education and hospitals throughout Russia.

Little has been written about the early life of Duke Constantine Petrovich. The record indicates he was baptised as a Protestant with the name Konstantin Friedrich Peter. But at court he was called by his Russian name and patronymic, Constantine Petrovich. He grew up in St. Petersburg during the 1850s. He had three brothers and four sisters.[1] The family spent summers at their residence in Kamenoi-Ostroff and retired to Peterhof Palace during the winters.

Duke Constantine Petrovich was registered from birth until 1869 as an Ensign in his father's honor unit, the Semenovsky Regiment of the Life Guard Infantry. He received his education at home and attended lectures at the Imperial School of Jurisprudence before entering military service on May 21, 1869.

Brothers and Sisters

The duke had 7 sisters and brothers. His sister Alexandra married into the House of Romanov while two other siblings married into the Beauharnais House of Leuchtenberg, who were considered part of the Imperial family.

- Duchess Alexandra Petrovna of Oldenburg (2 June 1838, St. Petersburg – 13 April 1900 Kiev, Ukraine); m. 1856 to Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia (1831–1891), the son of Tsar Nicholas I and commander-in-chief of the Russian Armies of the Danube in the Russo-Turkish War, 1877-1878. Their son, Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich of Russia (1856 - 1929) also served briefly as commander-in-chief of the Russian Army during the first year of World War I.

- Nicholas Friedrich August of Oldenburg (9 May 1840, St. Petersburg – 20 January 1886, Geneva, Switzerland); m. Maria Bulazel created Countess von Osternburg.

- Cecile of Oldenburg (27 February 1842 St. Petersburg – 11 January 1843, St. Petersburg)

- Duke Alexander Petrovich of Oldenburg (2 June 1844, St Petersburg, – 6 September 1932, Biarritz, France). Heir of the Russian Oldenburgs. He was once a candidate to the Bulgarian throne. He married in 1868 to Princess Eugenia Maximilianovna of Leuchtenberg. Their only son, Duke Peter Alexandrovich of Oldenburg, married the sister of Tsar Nicholas II, Grand Duchess Olga Alexandrovna of Russia.

- Katherine of Oldenburg (21 September 1846, St. Petersburg – 23 June 1866, St. Petersburg)

- George of Oldenburg (17 April 1848, St. Petersburg – 17 March 1871, St. Petersburg)

- Duchess Therese of Oldenburg (30 March 1852, St. Petersburg – 18 April 1883 St. Petersburg); m. George Maximilianovich, 6th Duke of Leuchtenberg (1852–1912)

Military career

From 1869 to his death in 1906, Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg was registered in the Life Guard's Preobrazhensky Regiment. During the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-78, the Preobrazhensky regiment distinguished itself in battle. Constantine Petrovich served as an adjutant stationed on the Caucasian Front in Georgia as part of the Russian Caucasus Corps under the overall command of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, the Governor General of the Caucasus.

Constantine Petrovich eventually rose to the rank of Lt. General of Kuban Cossacks.[2]

The Kuban Cossacks constituted 90 percent of the cavalry on the Caucasian front. These legendary horsemen won fame for numerous battles during the Russo-Turkish war, namely the Battles of Shipka Pass, the defense of Doğubeyazıt, and the final and victorious Battle of Kars, a decisive Russian victory over the Ottoman Empire.

Post War Years

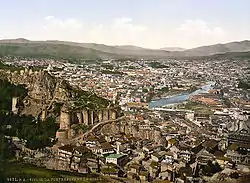

At the end of the war, between 1881 and 1887, Constantine Petrovich commanded the 1st Cavalry Regiment of the Hopersky Kuban Cossacks, stationed near Kutaisi, a town in the Georgian province of Imeretia, just north of the battlefield at Kars. He most likely remained under the command of Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich, who, as Governor General of the Caucasus, lived nearby in Tbilisi (then known as Tiflis).

At this time, the Black Sea coast in Georgia became the "Riviera of Russia," a popular place for wealthy Russians to visit on vacation, and the arts scene in Tiflis began to thrive. Constantine Petrovich became a guest at the social salon of Barbara Bonner Baratashvili ("Babale"), née Princess Cholokashvili, whose mansion at 9 Reutov Street attracted many poets, painters and writers.

It was here that Constantine Petrovich first saw the Imeretian noblewoman Agrippina Japaridze, his future wife. She was starring in the lead role of the play "The Knight in the Panther's Skin," a production mounted by Princess Cholokashvili in order to raise funds for a monument to one of Georgia's greatest poets, Shota Rustaveli.

Agrippina played Tinatin, an Arabian princess who sends her suitor on a quest to find a mysterious Knight in Panther's skin. The scenes and backdrops for the show were painted by the famous Hungarian court painter Mihály Zichy, and the play was a tremendous success, winning "endless applause."

After the show, Constantine Petrovich began a reckless flirtation with Agrippina and his attentions to the wife of a fellow officer caused people to gossip. Agrippina's husband, Prince Tariel "Taia" Dadiani, was one of the officers under Duke Constantine's command[3] It was considered very bad form to take advantage of one's rank in such a manner.

The Dadiani were a highly respected noble family in Georgia, its principal branch being in possession of the Principality of Mingrelia. Agrippina was Tariel Dadiani's second wife, and she had already given him three children: Prince Mikel (b.1860), Prince Levan (b.1864) and Princess Nino Dadiani (b.1868). Tariel's first wife was Princess Sophia Shervashidze (1838-1859), who died giving birth to their only child Princess Margareta (b.1859). Both Tariel's daughters married their cousins, Dadiani Princes from another branch of the family. Margareta married Prince Prince Giorgi Niko Dadiani (b.1855) and Nino married Prince Aleksandri Niko Dadiani (b.1864).

It is rumored that Constantine Petrovich finally won Agrippina from her husband while playing cards. The Duke allegedly agreed to cancel Dadiani's debts in exchange for his wife. When Prince Dadiani agreed, Agrippina left him.

On June 28, 1882, Agrippina divorced Dadiani. According to the memoirs of Counte Witte, Constantine Petrovich "had to marry her after she divorced her husband."[4] They wed that fall.

Marriage and issue

On 20 October 1882, Constantine entered into a morganatic marriage with a Georgian noblewoman Agrippina Japaridze, divorced Princess Dadiani, described by one source as wealthy and an "exceedingly lovely girl".[5] Grand Duke Peter II, head of the House of Oldenburg, created her Countess von Zarnekau on the day of their wedding, with the same title passing to their children. Between 1883 and 1892 they produced six children, all of them born in Kutais, the Caucasus:

- Alexandra Constantinovna von Zarnekau, Countess von Zarnekau (10 May 1883 - 28 May 1957); married Prince George Alexandrovich Yurievsky, a son of Alexander II of Russia.

- Ekaterina Konstantinovna von Zarnekau, Countess von Zarnekau (16 September 1884 - 24 December 1963)

- Nikolai Konstantinovich von Zarnekau, Count von Zarnekau (7 May 1886 - 1976)

- Aleksai Konstantinovich von Zarnekau, Count von Zarnekau (16 July 1887 - 16 September 1918)

- Petr Konstantinovich von Zarnekau, Count von Zarnekau (26 May 1889 - 1 November 1961)

- Nina Konstantinovna von Zarnekau, Countess von Zarnekau (13 August 1892 - 1922)

Professional and business career

After their marriage in 1882, the couple lived on the Japaridze family estate in Kutaisi. An able manager, Constantine Petrovich helped Agrippina to build her lands into productive vineyards and a winery. He established himself as a person interested in helping the region to develop its agriculture, especially the study of balneology and viticulture.

In 1884, they bought a local wine cellar established by the Frenchman Shote in 1876 for bottling champagne. They developed this into a thriving business that sold sparkling wines.

They also began an export company. Constantine Petrovich bought stock in local mines and oil wells, and began selling fruit, melons, vegetables and other farm goods abroad.

In his capacity as a cavalry general, Constantine Petrovich oversaw the local stables, gradually becoming an expert horse-trader, providing services to Russian officers and aristocrats in the region. The record indicates Constantine Petrovich became a member of the Veterinary Council of the Russian Empire, and he eventually became the "director general of all the Imperial horse-breeding establishments."[6]

By the early 1890s, they were doing business in Odessa, Ukraine. Duke Constantine also made regular visits to Alexandrovsk (Zaporozhe), home of the Zaparozhian cossacks, in order to buy and sell horses.

The Memoirs of Count Witte indicate that Duke Constantine and his family spent their vacations visiting with his sister, the Grand Duchess Alexandra Petrovna, at her summer palace in Kiev.

Palaces in Petersburg and Tiflis

In November 1894, Tsar Alexander III became ill with nephritis and died. When Tsar Nicholas II acceded to the throne, he allowed Duke Constantine Petrovich and his family to return to St. Petersburg.

Duke Constantine took a house at 36 Tavritcheskaia, next door to the building that later became the Tavricheskaya Art School in 1919. His eldest son, Count Nicholas von Zarnekau, a Cornette in His Supreme Majesty's Garde a Cheval (Horse Guards),[7] lived at 4 Konnogvardeisky Boulevard. Count Alexis von Zarnekau settled at 3 Alexandrovsky Prospekt.[8]

In 1895, Duke Constantine also bought from Amelia Titel a palace on what was then called Garden Street in Tiflis. On this land, Titel had commissioned a famous architect, Karl Stern, to build a large luxury villa. Designed in the "Brick Gothic" style, the Duke of Oldenburg's Palace served as the family's main residence in the Caucasus for the next ten years. In 2009, it was renovated and became an Art Palace, the Georgian State Museum of Theatre, Music, Cinema and Choreography at 6 Kargareteli Street, Tbilisi.

Controversial Wedding of Daughter

Constantine Petrovich did not improve matters in the year 1900, when he celebrated the wedding of his 17-year-old daughter, Countess Alexandra von Zarnekau, to the Tsar's half-uncle, Prince George Alexandrovich Yuryevsky at Nice, France.[9]

Prince George "Gogo" Yurievsky was the son of Tsar Alexander II and his secret mistress, Catherine Dolgorukov, the Princess Yurievskaya. Catherine, her son and two daughters were disliked intensely by Tsar Alexander III, whose mother, the Tsarina Maria Alexandrovna had been hurt and dishonored when Tsar Alexander II took Catherine Dolgorukov as his mistress in July 1866.[10] Because Catherine Dolgorukov urged the Tsar passionately to make liberal reforms, she was also greatly disliked by the political conservatives at court.[11]

After the death of Tsarina Maria Alexandrovna in June 1880, Tsar Alexander II married Catherine Dolgorukov, and made her three children legitimate. He gave each of them the new name Yurievsky and the rank of Prince or Princess. This caused a rumor at court that the Tsar wished for the newly legitimized Prince George Yourievsky to become the next Tsar, instead of his older and legitimate son, Alexander.

When bomb-throwing anarchists killed Tsar Alexander II on 1 March 1881, Tsar Alexander III wasted no time in getting rid of the Yourievsky family. Together with her three children, Princess Catherine was removed from the royal palace, banned from participation in the funeral procession, and eventually banished from Russia. As the new Tsar, Alexander III swiftly rolled back many of the liberal reforms his father had made.

Foreseeing this hostility, Tsar Alexander II had settled a large fortune on Princess Yurievsky—3.5 million rubles parked in Swiss bank accounts.[12] When she had arrived in France, she was reported to be very wealthy and found herself immediately surrounded by a circle of sympathetic Russian émigrés who hoped to receive her financial aid.

During the next 20 years, the Yurievsky circle in Paris and Nice remained under the surveillance of the Russian secret service.[12] The police reports indicate this group of wealthy Russian exiles and Georgian nationalists became involved in a number of secret plots.

Connection to Assassination Plots

In 1885, Baron Arthur von Mohrenheim, head of the Russian Okhrana (secret police) in Paris, reported to his replacement, Pyotr Rachkovsky, that the widowed Princess Yurievskaya had been using her money to finance a group of Russian nihilists who were attempting to kill Tsar Alexander III and his family. Rachkovsky dismissed the rumor as absurd.[13]

However, the rumor gained traction when a young Georgian nationalist, Prince Viktor Nakachidze, was convicted in late 1885 for participating in a nihilist bomb plot to kill the Tsar.[14] Through his Mingrelian relatives, Prince Victor Nakashidze had connections to Princess Agrippina Japaridze, the wife of Duke Constantine Petrovich, and to the Dadiani family -- Salome, Niko and Andria Dadiani—the Georgian royal family then living in exile at Nice.

For his role in the bomb plot, Prince Victor Nakachidze was sentenced to death and sent to Siberia. However, with the aid of his wife, Mlle. Roedel, he managed to escape, travelling across the Pacific to the United States. The couple eventually resurfaced in London.[15]

In 1890, Rachkovsky managed to entrap and convict Prince Victor Nakachidze and 26 of his associates as they prepared to set off bombs at the 1890 "Exposition Universelle" (World Fair) in Paris.[16] Once again, after serving only a few years in prison, Prince Nakachidze escaped.

In 1896, Prince Viktor Nakachidze resurfaced in Italy, where he gave up making bombs and masterminded an attempt to kill Tsar Nicholas II with poison. Observing that the Tsar often wore dress gloves, Nakachidze's circle studied the history of the Borgias at a local library in Milan, learned how to make powerful poisons, and recruited an agent in the palace at St. Petersburg to replace the Tsar's dress gloves with poison-coated gloves.

This murder attempt, reported in September 1896 by the international press, was very nearly successful. Doctors specializing in toxicology were summoned quickly to the palace and Tsar Nicholas made no public appearances for more than a week.[17]

Shortly after the marriage of Prince George Yurievsky to Countess Alexandra von Zarnekau at Nice in 1901, a connection between Prince Viktor Nakachidze and the Yurievsky circle in Nice became clear.

Nakachidze was arrested in Nice by French police "who affirm that they have full proof that the Prince was engaged in a plot to assassinate the Russian Emperor should he visit the Riviera."[18] The French jailed Nakachidze for two weeks, then released him. While attempting to rejoin his group in Milan, Prince Nakachidze was arrested again by Italian police at Rome.

On this occasion he gave a brief interview to the press and claimed that he was not an anarchist, but a patriot and a Georgian nationalist. He said he had returned to France, despite a long-standing banishment, because he was homeless and in great need of financial help.

Strangely, Prince Viktor Nakachidze claimed that he represented "a legitimate pretender to the Russian crown."[19] The only person living in Nice, France, who could reasonably have made a legitimate claim to the Russian crown was Prince George Yurievsky.

Tsar Nicholas II therefore had reason to look with suspicion on the marriage arranged in 1900 between the eldest daughter of Duke Constantine Petrovich and Prince George Yurievsky. Duke Constantine Petrovich appeared to be forging an alliance with the Yurievsky circle in Nice — a group that had a potentially valid claim to the Russian crown, and a wealthy group that now appeared to be offering financial aid to Prince Viktor Nakachidze, a well-known Georgian assassin and bomb-maker.

Death and Burial

Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg died of cancer at Nice, France, on 18 March 1906.[20] Sources disagree on the place of his burial. He is reported either to have been buried in Nice, or to have been buried near his father's grave in the Coastal Monastery of St. Sergius, traditional burial ground of the Russian Dukes of Oldenburg and Leuchtenberg. The royal graves at the monastery are no longer in evidence—they were either desecrated or lost during the Soviet period.

Honours

He received the following awards:[21]

- Russian honours

Knight of St. Vladimir, 4th Class with Swords and Bow, 1877

Knight of St. Vladimir, 4th Class with Swords and Bow, 1877.svg.png.webp) Knight of St. Stanislaus, 2nd Class with Swords, 1878

Knight of St. Stanislaus, 2nd Class with Swords, 1878 Knight of St. Anna, 2nd Class, 1884

Knight of St. Anna, 2nd Class, 1884- Golden Weapon "For Bravery", 1878

- Bronze Commemoration Medal for the Russo-Turkish War of 1877/78, 1878

- Bronze Commemoration Medal for the Coronation of Emperor Alexander III, 1883

- Foreign honours

Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 9 May 1850; with Swords, 26 March 1878 (Grand Duchy of Oldenburg)[22]

Grand Cross of the Order of Duke Peter Friedrich Ludwig, with Golden Crown, 9 May 1850; with Swords, 26 March 1878 (Grand Duchy of Oldenburg)[22] Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, 1850 (Mecklenburg)

Grand Cross of the Wendish Crown, with Crown in Ore, 1850 (Mecklenburg) Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1877 (Ernestine duchies)[23]

Grand Cross of the Saxe-Ernestine House Order, 1877 (Ernestine duchies)[23] Grand Cross of St. Alexander, 1883 (Principality of Bulgaria)

Grand Cross of St. Alexander, 1883 (Principality of Bulgaria) Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (Holy See)

Grand Cross of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem (Holy See) Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class (Ottoman Empire)

Order of Osmanieh, 1st Class (Ottoman Empire) Crossing of the Danube Cross, 1877 (United Principalities of Romania)

Crossing of the Danube Cross, 1877 (United Principalities of Romania).png.webp) Military Virtue Medal, 1879 (United Principalities of Romania)

Military Virtue Medal, 1879 (United Principalities of Romania) Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1879 (Kingdom of Württemberg)[24]

Grand Cross of the Württemberg Crown, 1879 (Kingdom of Württemberg)[24]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg |

|---|

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duke Constantine Petrovich of Oldenburg. |

- McIntosh, David. The Grand Dukes of Oldenburg, p. 372

- Ruvigny et Raineval, Melville H. The Titled Nobility of Europe. Harrison & Son, 1914, "Zarnekau"

- Harcave, Sidney, Trans. The Memoirs of Count Witte. New York: M.E. Sharp, 1990. Ch. IX Kiev in the 1880s, p. 79

- Witte, p. 80

- "Kings Servants Of The Poor Today", The Washington Post, 12 April 1906

- Washington Post, 2 Feb 1917, p. 6

- Ferrand, Jacques. Noblesse Russe: Portraits. Vol. 4, p. 41, Plate 78. "Nicholas Zarnekau"

- Ruvigny. "Zarnekau" pp. 1583 - 1584.

- "Not in Good Standing at Court" Washington Post, 2 Feb 1917, p. 6

- Alexandre Tarsaidze, Katia: Wife Before God, MacMillan (New York: 1970) p. 287

- Alex Butterworth, The World That Never Was, Vintage Books, New York, 2011, p. 146

- Perry and Pleshakov, p. 31

- Alex Butterworth, The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists & Secret Agents, Vintage Books (New York: 2011), p. 183

- Nihilists arrested, The Church Weekly, 18 January 1901, p. 44, Col. 3

- Marquise de Fontenoy, "Militant Princess without a Country," Washington Post, 18 June 1911, p. 4

- Alex Butterworth, The World that Never Was, Vintage Books (New York: 2011) pp. 266-267

- "Nihilists Resort to Borgia's Art: Plot to Kill the Czar by Impregnating His Gloves with Poison Almost Succeeds," [New York] World, 6 September 1896, p. 25, col. 5

- The Church Weekly, 18 January 1901, p. 44 Col. 3

- "Russian Prince Sentenced in Italy," New York Times, 2 October 1901

- 19 March 1906 New York Times

- Russian Imperial Army - Prince Konstantin Petrovich of Oldenburg (In Russian)

- Hof- und Staatshandbuch des Großherzogtums Oldenburg: 1879. Schulze. 1879. p. 31.

- Staatshandbücher für das Herzogtum Sachsen-Coburg und Gotha (1884), "Herzogliche Sachsen-Ernestinischer Hausorden" p. 32

- Hof- und Staats-Handbuch des Königreich Württemberg (1886/7), "Königliche Orden" p. 23

Resources

Butterworth, Alex. The World That Never Was: A True Story of Dreamers, Schemers, Anarchists & Secret Agents, New York: Vintage Books, 2011.

Harcave, Sidney (trans.) The Memoirs of Count Witte. New York: M.E. Sharp, 1990

Ferrand, Jacques. Noblesse Russe: Portraits. 1998.

Perry, John Curtis and Pleshakov, Constantine, The Flight of the Romanovs. Basic Books, 1999. ISBN 0-465-02462-9

Portraits: Grand-Duc Georges Alexandrovitch de Russie

Radzinsky, Edvard. Alexander II: The Last Great Tsar. Free Press, a division of Simon and Schuster, Inc., 2005. ISBN 978-0-7432-7332-9

Radziwill, Catherine. Behind the Veil at the Russian Court, Cassell & Co. Ltd. 1913

Ruvigny et Raineval, Melville H. The Titled Nobility of Europe. Harrison & Son, 1914.

Smithsonian Institution, "Andria Dadiani," Dadiani Dynasty website.

Smithsonian Institution, "Salome Dadiani and Her Descendants," Dadiani Dynasty website.