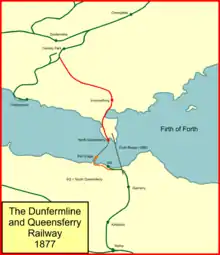

Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway

The Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway was a railway company founded to form part of a rail and ferry route between Dunfermline and Edinburgh, in Scotland. It was authorised in 1873 and its promoters had obtained informal promises from the larger North British Railway that the NBR would provide financial help, and also operate the ferry and the necessary railway on the southern side of the Firth of Forth.

In fact the NBR realised that the Forth Bridge would be built before long and that money spent on the Queensferry line would be wasted. They withdrew their support and the little company tried to build its line alone, but it soon ran out of money and had to sell out to the NBR.

The NBR completed the line and opened the south-side connecting line, but the opening of the Forth Bridge in 1890 reduced the Queensferry line to a minor branch line.

History

For centuries there have been a number of places where ferries took passengers and goods across the Forth, and one of these was at the narrow part of the Firth of Forth at Queensferry. When the Scottish railway network began to take shape from 1845, the two main northward routes authorised were to cross the Forth in Stirling, or to cross it directly opposite Edinburgh. The former course was taken by the Scottish Central Railway, which connected Castlecary on the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway with Perth via Stirling. The latter course was adopted by the Edinburgh and Northern Railway, which built its line from Burntisland to Perth and Tayport,[note 1] opposite Broughty, east of Dundee. The SCR route was considered a large detour by way of Falkirk and Larbert, but the E&NR route involved a significant ferry crossing, and a second one to cross the Tay to reach Dundee. The E&NR later introduced roll-on roll-off train ferries for goods and mineral wagons, avoiding transshipment.[1]

First railways authorised

The Edinburgh and Northern railway and the Scottish Central Railway were authorised in the 1845 Parliamentary session. The Edinburgh and Northern proposal had been controversial, and in particular a rival scheme, the Edinburgh and Perth Direct Railway, came a close second. The E&PDR wished to cross the Forth at Queensferry, thence running northwards through Dunfermline. For a time it looked as if the E&PDR scheme would be approved, but in fact it was eventually rejected by Parliament and disappeared from the scene. The railway through Fife to the north would cross at Burntisland.

These railways were substantially complete by 1849, and they were extremely popular and commercially successful. Nonetheless other routes continued to thrive, and the ferry at Queensferry was one such. It was encouraged by the fact that the railway route from Dunfermline to Edinburgh was extremely circuitous. There were two railways serving Dunfermline, a branch of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway (which had by now renamed itself the Edinburgh, Perth and Dundee Railway), and the Stirling and Dunfermline Railway. Reaching Edinburgh with the former involved travel by way of Thornton before turning south, and then enduring the ferry crossing. The latter also involved a large detour, through Stirling and Larbert. The difficulty of these indirect routes rankled with the citizens of Dunfermline, who many times petitioned the EP&DR and its successor, the North British Railway for a direct railway route. Many promises were given but the perception in Dunfermline was that the promises were worthless.[2]

Connecting Dunfermline by rail to Edinburgh

In 1861 the possibility of a Queensferry route seemed to have been revived, and three Bills went to Parliament to authorised such a line. One was the EP&DR's own line, to run from Dunfermline; an independent line was to run from Dunfermline to join the Edinburgh and Glasgow Railway; and the E&GR itself proposed a line from its own main line to Dunfermline. These three lines were essentially similar, and they all involved a ferry crossing at Queensferry. The ferry might involve roll-on roll-off arrangements as at Burntisland, and maybe there might even be a bridge, crossing from Blackness to Charlestown, a little to the west. The North British Railway had absorbed the EP&DR in 1862, and brought considerable additional financial power to the matter, yet seemingly without decisive action. Thus in 1864 the Fife Herald reported that:

As yet, there is no preparation for laying the trunk line between Edinburgh and Dunfermline and northwards to Perth. It appears that the North British Company are contemplating the abandonment of the route by the Queensferry, and the adoption of another higher up the Firth by means of a bridge. The report of the Directors says, "Another cause has dictated caution in the commencement of the expensive works on the southern portion of the Dunfermline Railway. The conviction has gradually become stronger, that a bridge over the Firth of Forth, at no great distance from Queensferry, might be erected without extravagant cost... In the present [Parliamentary] session, two bills have passed the second reading in the House of Commons, each containing application for power to erect a bridge... with this advantage, that the northern terminus of each of these bridges would abut upon the company's railway at Charleston, [sic] and this [would] open immediate communication with Edinburgh and Glasgow from Fife by means of its existing lines from Perth and Dundee via Dunfermline..."

Every one who reads this will easily spell out its real meaning--the abandonment of the Queensferry route--and the consequent abandonment of the whole design of an Edinburgh, Dunfermline and Perth railway, although it has received the sanction of Parliament. A bridge across the Firth at Charleston! Such an undertaking as this would cost a million of money,[note 2] and would be an act of folly very unlikely to be perpetrated by a covey of sharp-witted railway directors.[3]

The NBR firmly committed itself to the Forth Bridge at Charlestown in 1865, but the project was still on the back burner as the company gave the Tay Bridge priority. Thomas Bouch had designed the crossing, which was to involve two suspension bridge sections. But when the Tay bridge suffered a partial collapse in the Tay Bridge disaster in 1879, Bouch's work was naturally suspended. In 1882 the authorising Bill was passed in Parliament for the Forth Bridge that is in place today.[2][4]

The Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway

The pressure in Dunfermline for a better route to Edinburgh led to an excess of enthusiasm, encouraged by incautious hints from NBR directors, and it was supposed that a rail and ferry route via North Queensferry and Port Edgar, a pier opposite on the southern shore, was feasible. A Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway was put forward for the northern shore, and the NBR were understood to have promised a railway on the south side, connecting Port Edgar. Even better: a roll-on roll-off ferry, as at Burntisland, might be installed.

The Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway obtained Parliamentary authorisation by Act of 21 July 1873; there was to be an improved pier at North Queensferry for the ferry.

The North British Railway was involved with the company financially and in the Board of the D&QR, but by now it had become obvious within the NBR that the way forward was a Forth Bridge. The expenditure on that scheme would be huge, and any money diverted to connecting the Queensferry route would be wasted. The NBR nominees on the D&QR Board were instructed to do all they could to slow the rate of progress of the planning and construction of the railway. In June 1874 the NBR prevarication came to a head when the D&QR directors re-issued the company's prospectus, and decided to go it alone without the promised NBR financial support, which was obviously not going to be made available.[2][4]

This was not going to be easy as the available capital was scarce, but the first sod was cut on 3 April 1875. However only a part of the necessary capital was subscribed, and with their railway partly built, the Company had to accept that they had run out of money, and construction was halted. Realistically there was only one way out: a sale at a low price to the North British Railway. The Falkirk Herald reported the shareholders' meeting at which the painful truth was made known:

At an extraordinary meeting of the shareholders of the Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway, held at Dunfermline on Thursday [15 February 1877], the directors submitted the terms of amalgamation with the North British Railway. These they spoke of as disappointing, but stated that, under all the circumstances, and keeping in view the unexpected increases in the cost of constructing the railway, they had reluctantly come to the conclusion that they had no alternative but to recommend their acceptance. The amalgamation is to date from 31st July. The North British are to be entitled to all the assets and assume all the liabilities of the company; the fully paid-up share capital to become North British Preference Stock, bearing a fixed dividend of 3 per cent. per annum from 1st February 1878, with a lien on the line; they are to provide the necessary passenger accommodation at Port Edgar, and open the route from Edinburgh to Dunfermline via Queensferry without delay. After a lucid explanation of the state and prospects of the company, the Chairman, the Earl of Elgin, who said he had not the smallest possible trust in the promises of the North British directors, moved the approval and confirmation of the memorandum of amalgamation... [and] ultimately the heads of agreement were, by a majority, approved of.[5]

Elgin's view was hardly balanced: shareholders got 3% preference shares, and the NBR took the whole of the escalated debt of the D&QR.[4][6]

The NBR now hastened the completion of the D&QR, and it opened on 2 November 1877.[note 3] At the same time a short branch to Inverkeithing Harbour was built, partly on the trackbed of the Halbeath Railway.[1][4] There was a station in Dunfermline called Comely Park; it was renamed Dunfermline Lower on 5 March 1890.[7]

By the time the railway opened (by the NBR), local newspapers had decided that the NBR was the villain of the piece:

Opening of the Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway: Unaccompanied with ceremony of any kind, the new railway connecting Dunfermline with Edinburgh, by way of Queensferry, was opened on Thursday [1 November 1877]. The new line is six miles in extent... The travelling facilities which the new railway will afford--provided the North British Railway Company, who have become possessors of the line, put on a good and convenient service of trains, which as yet has not been done,--will prove of great benefit to the town of Dunfermline, and also to Inverkeithing... The towns named have lost considerably by the undertaking [presumably the delay in completion], but they are certain to benefit by the improved accommodation which will be supplied, and will be better equipped for competition in the race of enterprise and industry. The manufacturing interests, and the owners of the extensive coalfields in the west of Fife will now be in a much better position than formerly ...

[Dunfermline has been] shamefully neglected in respect of railway accommodation. For the last two decades the railway question has been a burning one in the old town... Over and again schemes were launched, and the North British Railway Company were approached, but the attempts were always futile until three years ago, when Provost Mathieson was urged on by influential representatives of the varied interests of the districts, to take the matter in hand... The beginning [of the D&QR project] was hopeful enough, but the cost exceeded what was expected, and the result of an amalgamation of the local company with the North British, on the condition that the latter completed the unfinished works, was that the shareholders lost considerably by the bargain. The first train conveying passengers left Comely Park Station, Dunfermline, a little after seven o'clock on Thursday morning... The passengers were not numerous, and on the train starting at Comely Park not a single cheer was raised...

For accommodation of every kind the station at Inverkeithing excels that of Dunfermline. At Queensferry the station and pier seem commodious and well finished... The service of trains, as we have indicated, is not nearly so perfect as it should be, neither had the public convenience been considered as it ought to have been. Surely, the North British Railway Company, who have made what is believed to be an excellent bargain, will show the Dunfermline and Inverkeithing people that they are not only disposed to be just but also generous.[8]

Even after the opening of the promised ferry and train connection, things were still wrong for the newspaper:

One of the pleasantest stage-coach routes still in existence is that between Edinburgh and Dunfermline. The journey is made in little more than a couple of hours when the ferry service is reliable, which it has not been for a considerable length of time. And the inconvenience became more intolerable after the opening of the Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway. The coaches from Edinburgh were conveyed across the ferry in the boat which took the railway passengers, who were first landed at the railway pier, while the boat with the coach on board had afterwards to proceed to the old landing-place. This, of course, necessitated a long and vexatious delay, which was the more inconvenient considering that the coach conveys the mails.[9]

On 2 June 1890 the Forth Bridge opened. Main line and local traffic could cross the Firth of Forth by the bridge, and ferry alternatives were immediately closed. The Dunfermline and Queensferry line continued in use, but was now a minor branch line. The approach to the Forth Bridge from Dunfermline used the original Dunfermline and Queensferry Railway route as far as Inverkeithing, and this was now converted to double track.[4]

Rosyth dockyard

A short connection off the Queensferry line to Rosyth Dockyard was opened on 1 January 1918, during World War I. Twenty trains daily ran from Edinburgh to the dockyard, carrying workmen and naval personnel. The dockyard connection remained in use after the end of the war, and although only sporadically used, is still available at the present day. North Queensferry itself closed to goods traffic in October 1954.[10]

After closure

In 2018 the tunnel at the North Queensferry end of the line was found to be degrading. The tunnel lies under the approach roads for the Forth Road Bridge. It was filled with polystyrene blocks and sealed off. The blocks can be removed in the future if the tunnel is ever re-opened.[11]

Station list

- North Queensferry; opened 1 November 1877; closed 5 March 1890; station transferred to the Forth Bridge line;

- Inverkeithing; opened 1 November 1877; still open;

- Rosyth Halt; opened unadvertised 28 March 1917; opened to public 1 December 1917; originally "Halt"; still open;

- Charlestown Junction; convergence of line from Charlestown and Kincardine;

- Dunfermline, Comely Park.[10][12]

- Rosyth Dockyard; Naval Base opened 1 July 1915; still used; workmen's passenger trains operated and official closure was on 24 November 1989, although it is thought that they ceased running some time before that.[10][12]

Notes

- The E&NR used the name Ferryport-on-Craig at first, and then the spelling Tay-Port.

- The Forth Bridge actually cost £3.2 million.

- Thomas, volume 1, page 242, says 1 April 1878; Brotchie and Jack say 1 November 1877.

References

- John Thomas, The North British Railway, volume 1, David & Charles, Newton Abbot, 1969, ISBN 0 7153 4697 0

- John Thomas and David Turnock, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: Volume 15, North of Scotland, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1989, ISBN 0 946537 03 8

- Fife Herald: Thursday 17 March 1864

- David Ross, The North British Railway: A History, Stenlake Publishing Limited, Catrine, 2014, ISBN 978 1 84033 647 4

- Falkirk Herald: Thursday 22 February 1877

- E F Carter, An Historical Geography of the Railways of the British Isles, Cassell, London, 1959

- Brotchie, Alan W; Jack, Harry (2007). Early Railways of West Fife: An Industrial and Social Commentary. Catrine: Stenlake Publishing. ISBN 9781840334098.

- Falkirk Herald: Thursday 8 November 1877

- Falkirk Herald: Thursday 6 December 1877

- Gordon Stansfield, Fife's Lost Railways, Stenlake Publishing, Catrine, 1998, ISBN 1 84033 055 4

- "Degrading tunnel in Fife filled with polystyrene". BBC Online. 19 April 2018. Retrieved 20 April 2018.

- M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002