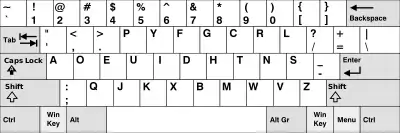

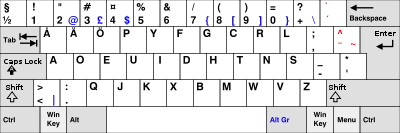

Dvorak keyboard layout

Dvorak /ˈdvɔːræk/ (![]() listen)[1] is a keyboard layout for English patented in 1936 by August Dvorak and his brother-in-law, William Dealey, as a faster and more ergonomic alternative to the QWERTY layout (the de facto standard keyboard layout). Dvorak proponents claim that it requires less finger motion and as a result reduces errors, increases typing speed, reduces repetitive strain injuries,[2] or is simply more comfortable than QWERTY.[3][4]

listen)[1] is a keyboard layout for English patented in 1936 by August Dvorak and his brother-in-law, William Dealey, as a faster and more ergonomic alternative to the QWERTY layout (the de facto standard keyboard layout). Dvorak proponents claim that it requires less finger motion and as a result reduces errors, increases typing speed, reduces repetitive strain injuries,[2] or is simply more comfortable than QWERTY.[3][4]

Although Dvorak has failed to replace QWERTY, most major modern operating systems (such as Windows,[5] macOS, Linux, Android, Chrome OS, and BSD) allow a user to switch to the Dvorak layout. iOS does not provide a system-wide, touchscreen Dvorak keyboard, although third-party software is capable of adding the layout to iOS, and the layout can be chosen for use with any hardware keyboard, regardless of printed characters on the keyboard.

Several modifications were designed by the team directed by Dvorak or by ANSI. These variations have been collectively or individually termed the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard, the American Simplified Keyboard or simply the Simplified Keyboard, but they all have come to be known commonly as the Dvorak keyboard or Dvorak layout.

Overview

Dvorak was designed with the belief that it would significantly increase typing speeds with respect to the QWERTY layout by alleviating some of its perceived shortcomings, such as:[6]

- Many common letter combinations require awkward finger motions.

- Some common letter combinations are typed with the same finger. (e.g. "ed" and "de")

- Many common letter combinations require a finger to jump over the home row.

- Many common letter combinations are typed with one hand while the other sits idle (e.g. was, were).

- Most typing is done with the left hand, which for most people is not the dominant hand.

- About 16% of typing is done on the lower row, 52% on the top row and only 32% on the home row.

August Dvorak studied letter frequencies and the physiology of the hand and created a new layout to alleviate the above problems, based on the following principles:[6]

- Letters should be typed by alternating between hands (which makes typing more rhythmic, increases speed, reduces error, and reduces fatigue). On a Dvorak keyboard, vowels and the most used symbol characters are on the left (with the vowels on the home row), while the most used consonants are on the right.

- For maximum speed and efficiency, the most common letters and bigrams should be typed on the home row, where the fingers rest, and under the strongest fingers (Thus, about 70% of letter keyboard strokes on Dvorak are done on the home row and only 22% and 8% on the top and bottom rows respectively).

- The least common letters should be on the bottom row which is the hardest row to reach.

- The right hand should do more of the typing because most people are right-handed.

- Digraphs should not be typed with adjacent fingers.

- Stroking should generally move from the edges of the board to the middle. An observation of this principle is that, for many people, when tapping fingers on a table, it is easier going from little finger to index than vice versa. This motion on a keyboard is called inboard stroke flow.[7]

The Dvorak layout is intended for the English language. For other European languages, letter frequencies, letter sequences, and bigrams differ from those of English. Also, many languages have letters that do not occur in English. For non-English use, these differences lessen the alleged advantages of the original Dvorak keyboard. However, the Dvorak principles have been applied to the design of keyboards for other languages, though the primary keyboards used by most countries are based on the QWERTY design.

The layout was completed in 1932 and granted U.S. Patent 2,040,248 in 1936.[8] The American National Standards Institute (ANSI) designated the Dvorak keyboard as an alternative standard keyboard layout in 1982 (INCITS 207-1991 R2007; previously X4.22-1983, X3.207:1991),[9] "Alternate Keyboard Arrangement for Alphanumeric Machines". The original ANSI Dvorak layout was available as a factory-supplied option on the original IBM Selectric typewriter.

History

August Dvorak was an educational psychologist and professor of education at the University of Washington in Seattle.[10] Touch typing had come into wide use by that time, and Dvorak became interested in the layout while serving as an advisor to Gertrude Ford, who was writing her master's thesis on typing errors. He quickly concluded that the QWERTY layout needed to be replaced. Dvorak was joined by his brother-in-law William Dealey, a professor of education at the then North Texas State Teacher's College in Denton, Texas.

Dvorak and Dealey's objective was to scientifically design a keyboard to decrease typing errors, speed up typing, and lessen typist fatigue. They engaged in extensive research while designing their keyboard layout. In 1914 and 1915, Dealey attended seminars on the science of motion and later reviewed slow-motion films of typists with Dvorak. Dvorak and Dealey meticulously studied the English language, researching the most used letters and letter combinations. They also studied the physiology of the hand. The result in 1932 was the Dvorak Simplified Keyboard.[11]

In 1893, George Blickensderfer had developed a keyboard layout for the Blickensderfer typewriter model 5 that used the letters DHIATENSOR for the home row. Blickensderfer had determined that 85% of English words contained these letters. The Dvorak keyboard uses the same letters in its home row, apart from replacing R with U, and even keeps the consonants in the same order, but moves the vowels to the left: AOEUIDHTNS.

In 1933, Dvorak started entering typists trained on his keyboard into the International Commercial Schools Contest, which were typing contests sponsored by typewriter manufacturers consisting of professional and amateur contests. The professional contests had typists sponsored by typewriter companies to advertise their machines. QWERTY typists became disconcerted by the rapid-fire clacking of the Dvorak typists, and asked for separate seating.[12]

In the 1930s, the Tacoma, Washington, school district ran an experimental program in typing designed by Dvorak to determine whether to hold Dvorak layout classes. The experiment put 2,700 highschool students through Dvorak typing classes and found that students learned Dvorak in one-third the time it took to learn QWERTY. When a new school board was elected, however, it chose to terminate the Dvorak classes.[12] During World War II, while in the Navy, Dvorak conducted experiments which he claimed showed that typists could be retrained to Dvorak in a mere 10 days, though he discarded at least two previous studies which were conducted and whose results are unknown.[13]

With such great apparent gains, interest in the Dvorak keyboard layout increased by the early 1950s. Numerous businesses and government organizations began to consider retraining their typists on Dvorak keyboards. In this environment, the General Services Administration commissioned Earle Strong to determine whether the switch from QWERTY to Dvorak should be made. After retraining a selection of typists from QWERTY to Dvorak, once the Dvorak group had regained their previous typing speed (which took 100 hours of training, more than was claimed in Dvorak's Navy test), Strong took a second group of QWERTY typists chosen for equal ability to the Dvorak group and retrained them in QWERTY in order to improve their speed at the same time the Dvorak typists were training.

The carefully controlled study failed to show any benefit to the Dvorak keyboard layout in typing or training speed. Strong recommended speed training with QWERTY rather than switching keyboards, and attributed the previous apparent benefits of Dvorak to improper experimental design and outright bias on the part of Dvorak, who had designed and directed the previous studies. However, Strong had a personal grudge against Dvorak and had made public statements before his study opposing new keyboard designs.[14] After this study, interest in the Dvorak keyboard waned.[13] Later experiments have shown that many keyboard designs, including some alphabetical ones, allow very similar typing speeds to QWERTY and Dvorak when typists have been trained for them, suggesting that Dvorak's careful design principles may have had little effect because keyboard layout is only a small part of the complicated physical activity of typing.[15]

The work of Dvorak paved the way for other optimized keyboard layouts for English such as Colemak, but also for other languages such as the German Neo and the French BÉPO.[16]

Original layout

Over the decades, symbol keys were shifted around the keyboard resulting in variations of the Dvorak design. In 1982, the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) implemented a standard for the Dvorak layout known as ANSI X4.22-1983. This standard gave the Dvorak layout official recognition as an alternative to the QWERTY keyboard.[17]

The layout standardized by the ANSI differs from the original or "classic" layout devised and promulgated by Dvorak. Indeed, the layout promulgated publicly by Dvorak differed slightly from the layout for which Dvorak & Dealey applied for a patent in 1932 – most notably in the placement of Z. Today's keyboards have more keys than the original typewriter did, and other significant differences existed:

- The numeric keys of the classic Dvorak layout are ordered: 7 5 3 1 9 0 2 4 6 8 (used today by the Programmer Dvorak layout[18])

- In the classic Dvorak layout, the question mark key [?] is in the leftmost position of the upper row, while the slash key [/] is in the rightmost position of the upper row.

- For the classic Dvorak layout, the following symbols share keys (the second symbol being printed when the SHIFT key is pressed):

- colon [:] and question mark [?]

- ampersand [&] and slash [/].

Modern U.S. Dvorak layouts almost always place semicolon and colon together on a single key, and slash and question mark together on a single key. Thus, if the keycaps of a modern keyboard are rearranged so that the unshifted symbol characters match the classic Dvorak layout then the result is the ANSI Dvorak layout.

Availability in operating systems

Dvorak is included with all major operating systems (such as Windows, macOS, Linux and BSD). Since the introduction of iOS 8 in 2014, Apple iPhone and iPad users have been able to install third party keyboards on their touchscreen devices which allow for alternative keyboard layouts such as Dvorak on a system wide basis.

Early PCs

Although some word processors could simulate alternative keyboard layouts by software, this was application specific; if more than one program was commonly used (e.g., a word processor and a spreadsheet), the user could be forced to switch layouts depending on the application. Occasionally, stickers were provided to place over the keys for these layouts.

However, IBM-compatible PCs used an active, "smart" keyboard. Striking a key generated a key "code", which was sent to the computer. Thus, changing to an alternative keyboard layout was accomplished most easily by simply buying a keyboard with the new layout. Because the key codes were generated by the keyboard itself, all software would respond accordingly. In the mid to late 1980s, a small industry for replacement PC keyboards developed; although most of these were concerned with keyboard "feel" and/or programmable macros, there were several with alternative layouts, such as Dvorak.

Amiga

Amiga operating systems from the 1986 version 1.2 onward allow the user to modify the keyboard layout by using the setmap command line utility with "usa2" as an argument, or later in 3.x systems by opening the keyboard input preference widget and selecting "Dvorak". Amiga systems versions 1.2 and 1.3 came with the Dvorak keymap on the Workbench disk. Versions 2.x came with the keymaps available on the "Extras" disk. In 3.0 and 3.1 systems, the keymaps were on the "Storage" disk. By copying the respective keymap to the Workbench disk or installing the system to a hard drive, Dvorak was usable for Workbench application programs.

Microsoft Windows

Versions of Microsoft Windows including Windows 95, Windows NT 3.51 and later have shipped with U.S. Dvorak layout capability.[5] Free updates to use the layout on earlier Windows versions are available for download from Microsoft.

Earlier versions, such as DOS 6.2/Windows 3.1, included four keyboard layouts: QWERTY, two-handed Dvorak, right-hand Dvorak, and left-hand Dvorak.

In May 2004, Microsoft published an improved version of its Keyboard Layout Creator (MSKLC version 1.3[19] – current version is 1.4[20]) that allows anyone to easily create any keyboard layout desired, thus allowing the creation and installation of any international Dvorak keyboard layout such as Dvorak Type II (for German), Svorak (for Swedish) etc.

Another advantage of the Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator with respect to third-party programs for installing an international Dvorak layout is that it allows creation of a keyboard layout that automatically switches to standard (QWERTY) after pressing the two hotkeys (SHIFT and CTRL).

Unix-based systems

Many operating systems based on UNIX, including OpenBSD, FreeBSD, NetBSD, OpenSolaris, Plan 9, and most Linux distributions, can be configured to use the U.S. Dvorak layout and a handful of variants. Furthermore, all current Unix-like systems with X.Org and appropriate keymaps installed (and virtually all systems meant for desktop use include them) are able to use any QWERTY-labeled keyboard as a Dvorak one without any problems or additional configuration. This eliminates the burden of producing additional keymaps for every variant of QWERTY provided. Runtime layout switching is also possible.

Chrome OS

Chrome OS and Chromium OS offer Dvorak, and there are three different ways to switch the keyboard to the Dvorak layout.[21] Chrome OS includes the US Dvorak and UK Dvorak layouts.

Apple computers

Apple had Dvorak advocates since the company's early (pre-IPO) days. Several engineers devised hardware and software to remap the keyboard, which were used inside the company and even sold commercially.

Apple II

The Apple IIe had a keyboard ROM that translated keystrokes into characters. The ROM contained both QWERTY and Dvorak layouts, but the QWERTY layout was enabled by default. A modification could be made by pulling out the ROM, bending up four pins, soldering a resistor between two pins, soldering two others to a pair of wires connected to a DIP switch, which was installed in a pre-existing hole in the back of the machine, then plugging the modified ROM back in its socket. The "hack" was reversible and did no damage. By flipping the switch, the user could switch from one layout to the other. This modification was entirely unofficial but was inadvertently demonstrated at the 1984 Comdex show, in Las Vegas, by an Apple employee whose mission was to demonstrate Apple Logo II. The employee had become accustomed to the Dvorak layout and brought the necessary parts to the show, installed them in a demo machine, then did his Logo demo. Viewers, curious that he always reached behind the machine before and after allowing other people to type, asked him about the modification. He spent as much time explaining the Dvorak keyboard as explaining Logo.

Apple brought new interest to the Dvorak layout with the Apple IIc, which had a mechanical switch above the keyboard whereby the user could switch back and forth between the QWERTY and Dvorak: this was the most official version of the IIe Dvorak mod. The IIc Dvorak layout was even mentioned by 1984 advertisements, which stated that the world's fastest typist, Barbara Blackburn, had set a record on an Apple IIc with the Dvorak layout.

Dvorak was also selectable using the built-in control panel applet on the Apple IIGS.

Apple III

The Apple III used a keyboard-layout file loaded from a floppy disk: the standard system-software package included QWERTY and Dvorak layout files. Changing layouts required restarting the machine.

Apple Lisa

The Apple Lisa did not offer the Dvorak keyboard mapping, though it was purportedly available through undocumented interfaces.[22]

Mac OS

In the early days, Macintosh users could only use the Dvorak layout by editing the "System" file using Apple's "RESource EDITor" ResEdit – which allowed users to create and edit keyboard layouts, icons, and other interface components.

By 1994, a package named 'Electric Dvorak' by John Rethorst provided an easily user-installable "implementation [that] was particularly good on pre-system 7 Macs" as freeware, and especially useful for Mac+ and Mac SE machines running MacOS 6 and 7.

Another third-party developer offered a utility program called MacKeymeleon, which put a menu on the menu bar that allowed on-the-fly switching of keyboard layouts. Eventually, Apple Macintosh engineers built the functionality of this utility into the standard system software, along with a few layouts: QWERTY, Dvorak, French (AZERTY), and other foreign-language layouts.

Since about 1998, beginning with Mac OS 8.6, Apple has included the Dvorak layout. It can be activated with the Keyboard Control Panel and selecting "Dvorak". The setting is applied once the Control Panel is closed out. Apple also includes a Dvorak variant they call "Dvorak – Qwerty ⌘". With this layout, the keyboard temporarily becomes QWERTY when the Command (⌘/Apple) key is held down. By keeping familiar keyboard shortcuts like "close" or "copy" on the same keys as ordinary QWERTY, this lets some people use their well-practiced muscle memory and may make the transition easier. Mac OS and subsequently Mac OS X allow additional "on-the-fly" switching between layouts: a menu-bar icon (by default, a national flag that matches the current language, a 'DV' represents Dvorak and a 'DQ' represents Dvorak – Qwerty ⌘) brings up a drop-down menu, allowing the user to choose the desired layout. Subsequent keystrokes will reflect the choice, which can be reversed the same way.

Mac OS X 10.5 "Leopard" and later offer a keyboard identifier program that asks users to press a few keys on their keyboards. Dvorak, QWERTY and many national variations of those designs are available. If multiple keyboards are connected to the same Mac computer, they can be configured to different layouts and use simultaneously. However should the computer shut down (lack of battery, etc.) the computer will revert to QWERTY for reboot, regardless of what layout the Admin was using.

Mobile phones and PDAs

A number of mobile phones today are built with either full QWERTY keyboards or software implementations of them on a touch screen. Sometimes the keyboard layout can be changed by means of a freeware third-party utility, such as Hacker's Keyboard for Android, AE Keyboard Mapper for Windows Mobile, or KeybLayout for Symbian OS.

The RIM BlackBerry lines offer only QWERTY and its localized variants AZERTY and QWERTZ. Apple's iOS 8.0 and later has the option to install onscreen keyboards from the App Store, which includes several free and paid Dvorak layouts. iOS 4.0 and later supports external Dvorak keyboards. Google's Android OS touchscreen keyboard can use Dvorak and other nonstandard layouts natively as of version 4.1.[23]

Comparison of the QWERTY and Dvorak layouts

Keyboard strokes

Touch typing requires typists to rest their fingers in the home row (QWERTY row starting with "ASDF"). The more strokes there are in the home row, the less movement the fingers must do, thus allowing a typist to type faster, more accurately, and with less strain to the hand and fingers.

The majority of the Dvorak layout's key strokes (70%) are done in the home row, claimed to be the easiest row to type because the fingers rest there. Additionally, the Dvorak layout requires the fewest strokes on the bottom row (the most difficult row to type). By contrast, QWERTY requires typists to move their fingers to the top row for a majority of strokes and has only 32% of the strokes done in the home row.[24]

Because the Dvorak layout concentrates the vast majority of key strokes to the home row, the Dvorak layout uses about 63% of the finger motion required by QWERTY, which is claimed to make the keyboard more ergonomic.[25] Because the Dvorak layout requires less finger motion from the typist compared to QWERTY, some users with repetitive strain injuries have reported that switching from QWERTY to Dvorak alleviated or even eliminated their repetitive strain injuries;[26][27] however, no scientific study has been conducted verifying this.[28]

The typing loads between hands differs for each of the keyboard layouts. On QWERTY keyboards, 56% of the typing strokes are done by the left hand. As the right hand is dominant for the majority of people, the Dvorak keyboard puts the more often used keys on the right hand side, thereby having 56% of the typing strokes done by the right hand.[24]

Awkward strokes

Awkward strokes are undesirable because they slow down typing, increase typing errors, and increase finger strain. The term hurdling refers to an awkward stroke requiring a single finger to jump directly from one row, over the home row to another row (e.g., typing "minimum" [which often comes out as "minimun" or "mimimum"] on the QWERTY keyboard).[29] In the English language, there are about 1,200 words that require a hurdle on the QWERTY layout. In contrast, there are only a few words requiring a hurdle on the Dvorak layout.[29][30]

Hand alternation and finger repetition

The QWERTY layout has more than 3,000 words that are typed on the left hand alone and about 300 words that are typed on the right hand alone (the aforementioned word "minimum" is a right-hand-only word). In contrast, with the Dvorak layout, only a few words are typed using only the left hand and even fewer use the right hand alone.[24] This is because most syllables require at least one vowel, and, in a Dvorak layout, all the vowels (and "y") fall on the left side of the keyboard. However, this benefit dwindles for longer words, because one English syllable can contain numerous consonants (as in "schmaltz" or "strengths").[31]

Standard keyboard

QWERTY enjoys advantages with respect to Dvorak due to the fact that it is the de facto standard keyboard:

- Keyboard shortcuts in most major operating systems, including Windows, are designed for QWERTY users, and can be awkward for some Dvorak users, such as Ctrl-C (Copy) and Ctrl-V (Paste). However, Apple computers have a "Dvorak – Qwerty ⌘" setting, which temporarily changes the keyboard mapping to QWERTY when the command (⌘) key is held, and Windows users can replicate this setting using AutoHotkey scripts.

- Some public computers (such as in libraries) will not allow users to change the keyboard to the Dvorak layout.

- Some standardized exams will not allow test takers to use the Dvorak layout (e.g. Graduate Record Examination).

- Support for Dvorak in games, especially those that make use of "WASD" – an ergonomic inverted-T shape using QWERTY but spread out across the keyboard in Dvorak – for in-game movement vary. Some games will automatically detect the keyboard is in Dvorak and adjust keys to the Dvorak equivalent, ",AOE", while others allow the same effect with some manual tweaking; games with hard-coded keybinds that do not allow changing the keys away from WASD become practically impossible to play under Dvorak.

- People who can touch type with a QWERTY keyboard will be less productive with alternative layouts until they retrain themselves, even if these are closer to the optimum.[32]

- Not all people use keyboard fingerings as specified in touch-typing manuals due to either preference or anatomical difference. This can change the relative efficiency on alternative layouts.

Variants

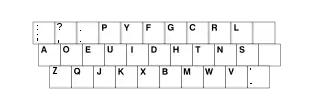

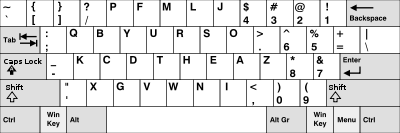

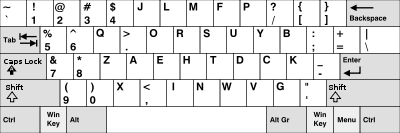

One-handed versions

In the 1960s, Dvorak designed left- and right-handed Dvorak layouts for touch-typing with only one hand. He tried to minimize the need to move the hand from side to side (lateral travel), as well as to minimize finger movement. Each layout has the hand resting near the center of the keyboard, rather than on one side.

Because the layouts require less hand movement than layouts designed for two hands, they can be more accessible to single-handed users. The layouts are also used by people with full use of two hands, who prefer having one hand free while they type with the other.

The left-handed Dvorak and right-handed Dvorak keyboard layouts are mostly each other's mirror image, with the exception of some punctuation keys, some of the less-used letters, and the 'wide keys' (Enter, Shift, etc.). Dvorak arranged the parentheses ")(" on his left-handed keyboard, but some keyboards place them in the typical "()" reading order. Illustrated here is Dvorak's original ")(" placement, above; it is the more widely distributed layout, not least because it is the one that ships with Windows.

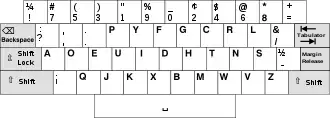

Programmer Dvorak

Programmer Dvorak was developed by Roland Kaufmann in the early 2000s and is designed for people writing code in C, Java, Pascal, Lisp, HTML, CSS and XML.[33]

While the letters are in the same places as the original layout, most symbols and numbers have been moved. The most noticeable difference is that the top row contains various brackets and other symbols, and you need to use the Shift key to type the numbers, like on typewriters. The numbers are arranged with the odds under the left hand and the evens under the right hand, as on Dvorak's original layout.

It comes preinstalled on Linux and installers are also available for macOS and Windows.

Research on efficiency

The Dvorak layout is designed to improve touch-typing, in which the user rests their fingers on the home row. It would have less effect on other methods of typing such as hunt-and-peck. Some studies show favorable results for the Dvorak layout in terms of speed, while others do not show any advantage, with many accusations of bias or lack of scientific rigour among researchers. The first studies were performed by Dvorak and his associates. These showed favorable results and generated accusations of bias.[34] However, research published in 2013 by economist Ricard Torres suggests that the Dvorak layout has definite advantages.[35]

In 1956, a study with a sample of 10 people in each group conducted by Earle Strong of the U.S. General Services Administration found Dvorak no more efficient than QWERTY[36] and claimed it would be too costly to retrain the employees.[32] The failure of the study to show any benefit to switching, along with its illustration of the considerable cost of switching, discouraged businesses and governments from making the switch.[37] This study was similarly criticised as being biased in favor of the QWERTY control group.[6]

In the 1990s, economists Stan Liebowitz and Stephen E. Margolis wrote articles in the Journal of Law and Economics[34] and Reason magazine[13] where they rejected Dvorak proponents' claims that the dominance of the QWERTY is due to market failure brought on by QWERTY's early adoption, writing, "[T]he evidence in the standard history of Qwerty versus Dvorak is flawed and incomplete. [..] The most dramatic claims are traceable to Dvorak himself; and the best-documented experiments, as well as recent ergonomic studies, suggest little or no advantage for the Dvorak keyboard."[34][38]

Resistance to adoption

Although the Dvorak design is the only other keyboard design registered with ANSI and is provided with all major operating systems, attempts to convert universally to the Dvorak design have not succeeded. The failure of Dvorak to displace QWERTY has been the subject of some studies.[34][39]

A discussion of the Dvorak layout is sometimes used as an exercise by management consultants to illustrate the difficulties of change. The Dvorak layout is often used in economics textbooks as a standard example of network effects,[40][41] though this method has been criticized.[34]

Most keyboards are based on QWERTY layouts, despite the availability of other keyboard layouts, including the Dvorak.

Other languages

Although DSK is implemented in many languages other than English, there are still potential issues. Every Dvorak implementation for other languages has the same difficulties as for Roman characters. However, other (occidental) language orthographies can have other typing needs for optimization (many are very different from English). Because Dvorak was optimized for the statistical distribution of letters of English text, keyboards for other languages would likely have different distributions of letter frequencies. Hence, non-QWERTY-derived keyboards for such languages would need a keyboard layout that might be quite different from the Dvorak layout for English.

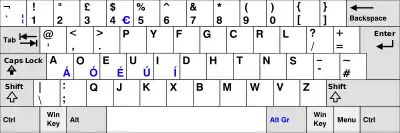

United Kingdom layouts

Whether Dvorak or QWERTY, a United Kingdom keyboard differs from the U.S. equivalent in these ways: the " and @ are swapped; the backslash/pipe [\ |] key is in an extra position (to the right of the lower left shift key); there is a taller return/enter key, which places the hash/tilde [# ~] key to its lower left corner (see picture).

The most notable difference between the U.S. and UK Dvorak layouts is the [2 "] key remains on the top row, whereas the U.S. [' "] key moves. This means that the query [/ ?] key retains its classic Dvorak location, top right, albeit shifted.

Interchanging the [/ ?] and [' @] keys more closely matches the U.S. layout, and the use of "@" has increased in the information technology age. These variations, plus keeping the numerals in Dvorak's idealised order, appear in the Classic Dvorak and Dvorak for the Left Hand and Right Hand varieties.

Svorak

The Svorak layout places the three extra Swedish vowels (å, ä and ö) on the leftmost three keys of the upper row, which correspond to punctuation symbols on the English Dvorak layout. This retains the original English DVORAK design goal of keeping all vowels by the left hand, including Y which is a vowel in Swedish.

The displaced punctuation symbols (period and comma) end up at the edges of the keyboard, but every other symbol is in the same place as in the standard Swedish QWERTY layout, facilitating easier re-learning. The Alt-Gr key is required to access some of the punctation symbols. This major design goal also makes it possible to "convert" a Swedish QWERTY keyboard to SVORAK simply by moving keycaps around.

Unlike for Norway, there's no standard Swedish Dvorak layout and the community is fragmented.[42] In Svdvorak, by Gunnar Parment, the punctuation symbols as they were in the English version; the first extra vowel (å) is placed in the far left of the top row while the other two (ä and ö) are placed at the far left of the bottom row.

Others

The Norwegian implementation (known as "Norsk Dvorak") is similar to Parment's layout, with "æ" and "ø" replacing "ä" and "ö".

The Danish layout DanskDvorak[43] is similar to the Norwegian.

An Icelandic Dvorak layout exists, created by a student at Reykjavik University. It retains the same basic layout as the standard Dvorak but features special Alt-Gr functions to allow easy usage for common characters such as "þ", "æ", "ö" and dead-keys to allow the typing of characters such as "å" and "ü".

A Finnish DAS keyboard layout[44] follows many of Dvorak's design principles, but the layout is an original design based on the most common letters and letter combinations of the Finnish language. Matti Airas has also made another layout for Finnish.[45] Finnish can also be typed reasonably well with the English Dvorak layout if the letters ä and ö are added. The Finnish ArkkuDvorak keyboard layout[46] adds both on a single key and keeps the American placement for each other character. As with DAS, the SuoRak[47] keyboard is designed by the same principles as the Dvorak keyboard, but with the most common letters of the Finnish language taken into account. Contrary to DAS, it keeps the vowels on the left side of the keyboard and most consonants on the right hand side.

The Turkish F keyboard layout (link in Turkish) is also an original design with Dvorak's design principles, however it's not clear if it is inspired by Dvorak or not. Turkish F keyboard was standardized in 1955 and the design has been a requirement for imported typewriters since 1963.

There are some non standard Brazilian Dvorak keyboard designs currently in development. The simpler design (also called BRDK) is just a Dvorak layout plus some keys from the Brazilian ABNT2 keyboard layout. Another design, however, was specifically designed for Brazilian Portuguese, by means of a study that optimized typing statistics, like frequent letters, trigraphs and words.[48]

The most common German Dvorak layout is the German Type II layout. It is available for Windows, Linux, and macOS. There is also the Neo layout[49] and the de ergo layout,[50] both original layouts that also use many of Dvorak's design principles. Because of the similarity of both languages, even the standard Dvorak layout (with minor modifications) is an ergonomic improvement with respect to the common QWERTZ layout. One such modification puts ß at the shift+comma position and the umlaut dots as a dead key accessible via shift+period (standard German keyboards have a separate less/greater key to the right of the left shift key).

For French, there is a Dvorak layout[51] and the Bépo layout, which is founded on Dvorak's method of analysing key frequency.[52] Although Bépo's placement of keys is optimised for French, the scheme also facilitates key combinations for typing characters of other European languages, Esperanto and various symbols.[16]

Three Spanish[53] layouts exist.

A Romanian version of the Dvorak layout was released in October 2008. It is available for both Windows and Linux.[54]

Polish propositions of national keyboard layout smiliar to Dvorak were created in 1950s, but weren't introduced due to new version of Polish Norm in 1958 with modernized QWERTZ layout.[55]

See also

References

- Wells, John C. (2008). Longman Pronunciation Dictionary (3rd ed.). Longman. ISBN 978-1-4058-8118-0.

- "Alternative Keyboard Layouts". Microsoft. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- Baker, Nick (August 11, 2010). "Why do we all use qwerty keyboards?". BBC Corporation. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- Andrei (May 2006). "The Qwerty Keyboard Layout Vs The Dvorak Keyboard Layout". Archived from the original on December 5, 2013. Retrieved December 22, 2011.

- "Alternative Keyboard Layouts". microsoft.com. Microsoft. Archived from the original on March 7, 2017.

- Noyes, Jan (August 1988). "The QWERTY keyboard: a review". International Journal of Man-Machine Studies. 18 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1016/S0020-7373(83)80010-8.

- Cassingham 1986, p. 34

- "US patent # 2040248". Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- "ANSI INCITS 207-1991 (R2007)". Archived from the original on October 13, 2014. Retrieved September 6, 2013.

- Dvorak, August et al. (1936). Typewriting Behavior. American Book Company. Title page.

- Cassingham 1986, pp. 32–35

- Robert Parkinson. "The Dvorak Simplified Keyboard: Forty Years of Frustration". Archived from the original on March 25, 2010. Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- "Typing Errors". Reason.com.

- Joe Kissell. "The Dvorak Keyboard Controversy". Retrieved May 3, 2014.

- Anson, Dennis. "Efficacy of Alternate Keyboard Configurations: Dvorak vs. Reverse-QWERTY". Assistive Technology Research Institute. Misericordia University. Archived from the original on April 26, 2015. Retrieved April 13, 2015.

- "bépo official website". Retrieved December 21, 2014.

- Cassingham 1986, pp. 35–37

- Kaufmann, Roland. "Programmer Dvorak". Retrieved May 29, 2012.

- "Download details: Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator (MSKLC) Version 1.3.4073". Microsoft.com. May 20, 2004. Archived from the original on January 28, 2010. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- "The Microsoft Keyboard Layout Creator". Msdn.microsoft.com. Retrieved January 21, 2010.

- Carwin Young. "Setting Your Input Format To Dvorak". Retrieved June 3, 2015.

- "Newegg Community". eggxpert.com.

- "Welcome to Android 4.1, Jelly Bean!". Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- Jared Diamond. "The Curse of QWERTY". Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Ober, Scot. "Relative Efficiencies of the Standard and Dvorak Simplified Keyboards". Retrieved April 29, 2010.

- Jonathan Oxer (December 10, 2004). "Wrist Pain? Try the Dvorak Keyboard". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Michael Samson. "Michael Sampson on the Dvorak Keyboard". Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Klosowski, Thorin (October 18, 2013). "Should I Use an Alternative Keyboard Layout Like Dvorak?". Lifehacker. Retrieved January 8, 2015.

- Jared Diamond. "The Curse of QWERTY". Retrieved April 26, 2010.

- William Hoffer (1985). "The Dvorak keyboard: is it your type?". Nation's Business. Archived from the original on May 26, 2012. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- Wakamatsu, Haley. "One-handed typing on QWERTY vs. Dvorak". FizzyStack. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- Strong, E.P. (1956). A Comparative Experiment in Simplified Keyboard Retraining and Standard Keyboard Supplementary Training (Report). Washington, D.C., USA: U.S. General Services Administration. OCLC 10066330. Retrieved July 14, 2018.

- Kaufmann, Roland. "Programmer Dvorak". Retrieved October 28, 2019.

- Liebowitz, Stan J.; Stephen E. Margolis (April 1990). "The Fable of the Keys". Journal of Law & Economics. 33 (1): 1–25. doi:10.1086/467198. S2CID 14262869. Retrieved September 19, 2007.

We show that David's version of the history of the market's rejection of Dvorak does not report the true history, and we present evidence that the continued use of Qwerty is efficient given the current understanding of keyboard design.

- Torres, Ricard (June 2013). "QWERTY vs. Dvorak Efficiency: A Computational Approach". S2CID 26820338. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Kissel, Joe. "The Dvorak Keyboard Controversy". Retrieved June 14, 2011.

- "US Balks at Teaching Old Typists New Keys". New York Times. July 2, 1956.

- Liebowitz, Stan J.; Margolis, Stephen E. (2001). "The Fable of the Keys". Winners, Losers and Microsoft. Oakland, Calif.: Independent Inst. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-945999-84-3.

- David, Paul A. (May 1985). "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY". American Economic Review. 75: 332–37. and David, Paul A. (1986). "Understanding the Economics of QWERTY: The Necessity of History.". In W. N Parker. (ed.). Economic History and the Modern Economist. New York: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-14799-2.

- Clements, M.T. (2005). "Inefficient Standard Adoption: Inertia and Momentum Revisited". Economic Inquiry. 43 (3): 507–518. doi:10.1093/ei/cbi034.

- Liebowitz, S.J.; S.E. Margolis (1994). "Network Externality: An Uncommon Tragedy". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 8 (2): 133–150. doi:10.1257/jep.8.2.133.

- Svorak/Dvorak?

- Dansk Dvorak – Dvorak er et ergonomisk tastatur layout. Museskade? prøv det ergonomiske Keyboard: Dvorak

- "Näppäimistö suomen kielelle". seres.fi.

- "Airas-keyboard". mairas.net. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012.

- "ArkkuDvorak: A Finnish Dvorak keyboard layout". arkku.com.

- "SuoRak". mbnet.fi. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011.

- "O que é o teclado brasileiro?". Archived from the original on July 3, 2006. Retrieved June 8, 2006.

- Hanno Behrens. "NEO keyboard". schattenlauf.de.

- "de-ergo – Forschung bei Goebel Consult". Archived from the original on July 10, 2007. Retrieved December 11, 2008.

- "Clavier Dvorak-fr : Accueil". algo.be.

- "Disposition de clavier francophone et ergonomique bépo". bepo.fr.

- "Dvorak keyboard layouts". programandala.net.

- "Învaţă singur - de Nicolae M. Popa". invatasingur.ro.

- http://tachygrafia.blogspot.com/2012/02/polski-ukad-klawiatury-cz-ii.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dvorak keyboard layouts. |

- DvZine.org – A print and webcomic zine advocating Dvorak and teaching its history.

- A Basic Course in Dvorak – by Dan Wood

- Dvorak your way with by Dan Wood and Marcus Hayward

- – Comparison of common optimal keyboard layouts, including Dvorak.

- Programmer Dvorak – a variant of the Dvorak layout for programmers by Roland Kaufmann.