Early 1970

"Early 1970" is a song by English musician Ringo Starr, released in April 1971 as the B-side to his hit single "It Don't Come Easy". It was inspired by the break-up of the Beatles and documents Starr's relationship with his former bandmates, John Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison. The lyrics to the verses comment in turn on each of the ex-Beatles' personal lives and the likelihood of each of them making music with Starr again; in the final verse, Starr acknowledges his musical limitations before expressing the hope that all the former Beatles will play together in the future. Commentators have variously described "Early 1970" as "a rough draft of a peace treaty"[1] and "a disarming open letter" from Starr to Lennon, McCartney and Harrison.[2]

| "Early 1970" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

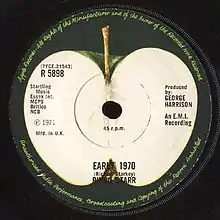

B-side label of "It Don't Come Easy" | ||||

| Single by Ringo Starr | ||||

| A-side | "It Don't Come Easy" | |||

| Released | 9 April 1971 | |||

| Recorded | October 1970 Abbey Road Studios, London | |||

| Genre | Rock, country | |||

| Length | 2:21 | |||

| Label | Apple | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Richard Starkey | |||

| Producer(s) | Ringo Starr | |||

| Ringo Starr singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

Starr recorded the song, under its working title "When Four Nights Come to Town", in London in October 1970, midway through the sessions for Lennon's John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band album. The recording features musical contributions from Harrison and German bass player Klaus Voormann, and some Beatles biographers suggest that Lennon might have participated also.

Background and composition

Writing in 1981, NME critic Bob Woffinden described the effect of the Beatles' break-up on drummer Ringo Starr as "shattering".[3] Although the official announcement came on 10 April 1970,[4] the group's demise was initiated by John Lennon's statement during a September 1969 band meeting that he wanted a "divorce" from his fellow Beatles.[5] In a February 1970 interview in Look magazine, midway through sessions for his first solo album, Sentimental Journey,[6] Starr explained his disorientation: "I keep looking around and thinking where are they? What are they doing? When will they come back and talk to me?"[7] Author Bruce Spizer suggests that these sentiments "form the basis" of Starr's composition "Early 1970".[7]

The four verses of the song refer to each of the Beatles in turn,[8] providing what Beatles Forever author Nicholas Schaffner describes as "a disarming open letter" to Lennon, Paul McCartney and George Harrison.[2] The song's working title was variously "When I Come to Town (Four Nights in Moscow)"[9] and "When Four Nights Come to Town",[1] and the lyrics gauge Starr's relationships with his bandmates according to how likely each one was to play music with Starr in the future.[10][11]

In the first verse, Starr addresses his strained relationship with McCartney, whose refusal to have his own debut solo album held back in Apple Records' release schedule, to allow for Sentimental Journey and the Beatles' Let It Be album,[12] led to a confrontation between the two musicians.[13] The incident took place at McCartney's St John's Wood home on 31 March 1970 and, according to Beatles biographer Peter Doggett, had a "grievous effect" on Starr and McCartney's friendship,[14] contributing to the latter announcing his departure from the band.[15] In "Early 1970", Starr's lyrics refer to McCartney's domestic situation,[2] on his Scottish property with wife Linda Eastman and their newborn daughter Mary:[16]

Lives on a farm, got plenty of charm, beep, beep

He's got no cows but he's sure got a whole lotta sheep

And brand new wife and a family

And when he comes to town I wonder if he'll play with me.

In verse two, Starr refers to Lennon and wife Yoko Ono's 1969 bed-ins for peace[1] and, in the line "They screamed and they cried, now they're free", to their more recent experiences with Arthur Janov's primal therapy treatment.[7] The latter experiences inspired the couple's 1970 solo albums, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band,[17] both of which feature Starr on drums.[18] He also screams the word "Cookies!" in a guttural manner, similar to Cookie Monster on Sesame Street. Lennon was known to love the Cookie Monster character and frequently would shout the word out of nowhere in a similar matter, including for the song "Hold On", which Starr played on.[19] The verse ends with Starr's optimistic comment on Lennon: "And when he comes to town, I know he's gonna play with me."[7]

In the third verse, Starr describes Harrison as "a long-haired, cross-legged guitar picker"[20] whose "long-legged" wife, former model Pattie Boyd, is "in the garden picking daisies" for his vegetarian meals.[7] Author Robert Rodriguez suggests that Harrison's workload following the September 1969 release of the Beatles' Abbey Road album displayed the same "workaholic tendencies" traditionally associated with McCartney,[21] and a number of these projects involved Starr.[22][nb 1] In contrast to McCartney and Lennon in "Early 1970", Starr views Harrison as "always in town playing for you with me", so much so that the guitarist spends little time at his recently purchased Friar Park estate.[1]

In the song's autobiographical final verse, Starr refers to his own musical shortcomings:[2][26]

I play guitar – A, D, E

I don't play bass, 'cause that's too hard for me

I play the piano if it's in C ...

He then concludes the song by declaring, "And when I go to town I wanna see all three" – a statement that Woffinden takes as being an admission by Starr that he "clearly needed the support" of Lennon, McCartney and Harrison.[8] Musically, "Early 1970" is in the country music genre, which Starr explored more fully on his Beaucoups of Blues album,[27] a project that arose from working with Nashville musician Pete Drake on Harrison's All Things Must Pass triple album in June 1970.[28]

Recording

Starr taped the basic track for the song, as "When I Come to Town (Four Knights in Moscow)", at Abbey Road Studios on 3 October 1970,[9] during a lull in the sessions for John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.[1][nb 2] In their book Eight Arms to Hold You, authors Chip Madinger and Mark Easter note the difficulty in ascertaining reliable information on the song's recording;[9] Spizer similarly cites "[f]ading memories" as a hindrance to identifying the precise line-up of musicians.[7] Starr biographer Alan Clayson suggests that Lennon produced this initial session,[31] while Doggett writes of Lennon merely participating in the recording, along with Starr and German bassist Klaus Voormann.[1][nb 3] According to Madinger and Scott Raile, writing in the 2015 book Lennonology, Lennon was at home with Ono and his son Julian at the time.[33] Starr subsequently completed the track with Harrison,[1] who finished his production of the drummer's "It Don't Come Easy" at this time.[9][nb 4]

In addition to his drum part, Starr is thought to have played rhythm acoustic guitar on "Early 1970".[11][36] According to Voormann's recollection, Starr overdubbed the opening dobro part and, in verse four, brief snatches of the various instruments on which he admits his musical limitations: the three guitar chords he names, a walking bass line, and a piano vamp following the third line of the verse.[7] Harrison played rhythm and lead electric guitar,[36] and a slide guitar part of which Madinger and Easter write: "George's distinctive slide solo after his 'section' of the song confirms his solidarity with Ringo, if nothing else."[9] Harrison also joined Starr on piano for the verse-four segment – "hacking away at the top of the keys", in Spizer's words.[7] Although American musician Gary Wright overdubbed piano on "It Don't Come Easy" that same month,[37] no one is credited for "Early 1970"'s main piano part.[36]

Allen Klein, the manager of Starr, Harrison and Lennon, suggested inviting McCartney to participate in the recording of the song, thinking that his involvement would undermine any legal moves McCartney might make to quit the Beatles.[38] No such collaboration took place, and McCartney filed a suit in London's High Court on 31 December to dissolve the band's business partnership.[39]

Release and reception

Starr selected "Early 1970" as the B-side for his first solo single in the UK, the lead side of which was "It Don't Come Easy".[37] The single was issued on Apple Records as R 5898, on 9 April 1971, with a US release following on 16 April (as Apple 1831).[40] While noting the "instant self-esteem" that the single's commercial success brought Starr, Alan Clayson opines that "Early 1970" would have "gone in one ear and out the other" had it not been for the song's subject matter.[41] Peter Doggett writes of the track having been "a rough draft of a peace treaty" originally, yet its release took place amid the unpleasantness surrounding the Beatles' lawsuit, making "Early 1970" "seem like a false memory of a mythic past, its Arcadia tangled with weeds".[42] Writing in 1973 – by which time the four ex-Beatles had united against Klein[43] – Alan Betrock of Phonograph Record reflected on the former bandmates' "backward glances" since the break-up, and opined: "Ringo's little-known B-side 'Early 1970' was probably the sharpest commentary on their whole lot."[44] In a 1976 review for the NME, Bob Woffinden dismissed it as "a period curiosity, interesting at the time, but of little substance".[45]

Robert Rodriguez describes the song as "utterly charming" with "a delicious slide guitar part", and adds: "'Early 1970' was the perfect tonic for beleaguered Beatles fans wondering if the band would ever, if not get back together, at least achieve some civility."[10] Bruce Spizer similarly views the song as a "charming delight".[46]

Re-releases

"Early 1970" received a second commercial release in November 1975, when included on Starr's Apple compilation Blast from Your Past.[47] For the 1991 CD reissue of Ringo (1973), the original ten-song album was expanded with the addition of three bonus tracks,[48] one of which was "Early 1970".[49] It also appeared on Photograph: The Very Best of Ringo Starr, issued in 2007.[50]

Personnel

- Ringo Starr – vocals, drums, acoustic guitar, dobro, standup bass (fill), piano (fill), backing vocals

- George Harrison – electric guitars, slide guitar, piano (fill)

- Klaus Voormann – bass

- uncredited – piano

Notes

- The projects included sessions for American singer Leon Russell[23] and Harrison-produced albums by Apple artists Billy Preston[24] and Doris Troy.[25]

- Some commentators suggest that the mention of "cookies" in the lyrics to Lennon's Plastic Ono Band track "Hold On" led to Starr including the word in his "Early 1970" verse about Lennon.[29][30]

- Neither Madinger and Easter nor Spizer acknowledge Lennon on the recording, for which Starr is credited as sole producer.[32]

- Harrison was at Abbey Road carrying out final mixing on All Things Must Pass[34] while Lennon and Starr were recording Plastic Ono Band.[35]

References

- Doggett, p. 145.

- Schaffner, p. 140.

- Woffinden, p. 44.

- Badman, p. 4.

- Doggett, pp. 103–04.

- Miles, pp 369, 370.

- Spizer, p. 294.

- Woffinden, p. 45.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 498.

- Rodriguez, pp. 29–30.

- Clayson, p. 220.

- Clayson, p. 206.

- Doggett, pp. 120, 122.

- Doggett, pp. 121–22.

- Woffinden, pp. 32–33.

- O'Dell, pp. 122–23.

- Clayson, p. 217.

- Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 171, 183.

- https://www.beatlesbible.com/people/john-lennon/songs/hold-on/

- Rodriguez, p. 29.

- Rodriguez, p. 1.

- Clayson, pp. 202–05.

- O'Dell, pp. 106–07.

- "Billy Preston Encouraging Words", Apple Records (retrieved 3 July 2013).

- Leng, p. 61.

- Rodriguez, p. 30.

- Spizer, pp. 287, 294.

- Clayson, pp. 207–08.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 37, 498.

- Spizer, pp. 34, 294.

- Clayson, p. 218.

- Castleman & Podrazik, pp. 100, 210.

- Madinger, Chip; Raile, Scott (2015). Lennonology: Strange Days Indeed – A Scrapbook of Madness. Chesterfield, MO: Open Your Books. pp. 210–11. ISBN 978-1-63110-175-5.

- Badman, p. 14.

- Hertsgaard, p. 308.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 210.

- Spizer, pp. 293–94.

- Doggett, p. 149.

- Badman, p. 19.

- Castleman & Podrazik, p. 100.

- Clayson, pp. 219–20.

- Doggett, pp. 145, 163–64.

- Rodriguez, p. 137.

- Betrock, Alan (December 1973). "Ringo Starr: Ringo". Phonograph Record. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Woffinden, Bob (3 January 1976). "Ringo Starr: Blast From Your Past". NME. Available at Rock's Backpages (subscription required).

- Spizer, p. 298.

- Madinger & Easter, p. 646.

- Madinger & Easter, pp. 507, 645.

- Ruhlmann, William. "Ringo Starr Ringo". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Ringo Starr Photograph: The Very Best of Ringo Starr". AllMusic. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

Sources

- Badman, Keith (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 2: After the Break-Up 1970–2001. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-8307-6.

- Castleman, Harry; Podrazik, Walter J. (1976). All Together Now: The First Complete Beatles Discography 1961–1975. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-25680-8.

- Clayson, Alan (2003). Ringo Starr. London: Sanctuary. ISBN 1-86074-488-5.

- Doggett, Peter (2011). You Never Give Me Your Money: The Beatles After the Breakup. New York, NY: It Books. ISBN 978-0-06-177418-8.

- Hertsgaard, Mark (1996). A Day in the Life: The Music and Artistry of the Beatles. London: Pan Books. ISBN 0-330-33891-9.

- Leng, Simon (2006). While My Guitar Gently Weeps: The Music of George Harrison. Milwaukee, WI: Hal Leonard. ISBN 978-1-4234-0609-9.

- Madinger, Chip; Easter, Mark (2000). Eight Arms to Hold You: The Solo Beatles Compendium. Chesterfield, MO: 44.1 Productions. ISBN 0-615-11724-4.

- Madinger, Chip; Raile, Scott (2015). LENNONOLOGY Strange Days Indeed - A Scrapbook Of Madness. Chesterfield, MO: Open Your Books, LLC. ISBN 978-1-63110-175-5.

- Miles, Barry (2001). The Beatles Diary Volume 1: The Beatles Years. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 0-7119-8308-9.

- O'Dell, Chris; Ketcham, Katherine (2009). Miss O'Dell: My Hard Days and Long Nights with The Beatles, The Stones, Bob Dylan, Eric Clapton, and the Women They Loved. New York, NY: Touchstone. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Rodriguez, Robert (2010). Fab Four FAQ 2.0: The Beatles' Solo Years, 1970–1980. Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4165-9093-4.

- Schaffner, Nicholas (1978). The Beatles Forever. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-055087-5.

- Spizer, Bruce (2005). The Beatles Solo on Apple Records. New Orleans, LA: 498 Productions. ISBN 0-9662649-5-9.

- Woffinden, Bob (1981). The Beatles Apart. London: Proteus. ISBN 0-906071-89-5.