Edward King (bishop of Lincoln)

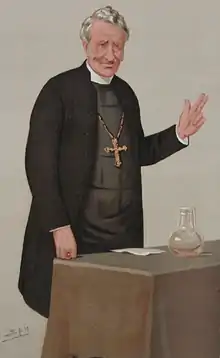

Edward King (29 December 1829 – 8 March 1910) was a bishop of the Church of England.

Life

King was the second son of Walker King, Archdeacon of Rochester and rector of Stone, Kent, and grandson of Walker King, Bishop of Rochester; his nephew was Robert King, a priest and canon who played football for England in 1882. His mother, Anne, was the daughter of William Heberden the Younger (1767–1845), Physician in Ordinary to George III.

King graduated from Oriel College, Oxford. He was ordained in 1854 and four years later became chaplain and lecturer at Cuddesdon Theological College (now Ripon College Cuddesdon). He was principal at Cuddesdon from 1863 to 1873, when the prime minister, William Ewart Gladstone, appointed him Regius Professor of Pastoral Theology at Oxford and canon of Christ Church.[1]

Prominent Anglo-Catholic

King became the principal founder of the leading Anglo-Catholic theological college in the Church of England, St Stephen's House, Oxford, now a Permanent Private Hall of the University of Oxford. To the world outside, King was known at this time as an Anglo-Catholic and one of Edward Pusey's most intimate friends (even serving as a pall-bearer at his funeral in 1882), but in Oxford, and especially among the younger men, he exercised influence by his charm and sincerity.[1] King had also been devoted to his mother, who assisted him at Cuddesdon and Oxford by keeping his house and entertaining guests as his position required. King never married and his mother died in 1883.

A leading member of the English Church Union, King fought prosecutions in lay courts under the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874 (which Archibald Campbell Tait, Archbishop of Canterbury, and the prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, had secured over Gladstone's opposition in order to restrict the growing Oxford Movement). In 1879 King's writings concerning Holy Communion were criticised as "Romish" in a pamphlet by a local vicar.[2]

Bishop of Lincoln

In 1885, upon Gladstone's invitation when he again became prime minister, King accepted consecration as Bishop of Lincoln,[3] which he noted had been the diocese of John Wesley. The consecrating bishops included Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury, with presenting bishops John Mackarness, Bishop of Oxford and James Woodford, Bishop of Ely. Other consecrating bishops were Frederick Temple, Bishop of London; Anthony Thorold, Bishop of Rochester; Ernest Wilberforce, Bishop of Newcastle; Edward Trollope, Bishop of Nottingham; Walsham How, Bishop of Bedford; William Boyd Carpenter, Bishop of Ripon; and Henry Bousfield, Bishop of Pretoria.[4]

Although Tait had died in 1882, the Puritan faction continued to voice its objections, including at Lincoln where J. Hanchard published a sketch of King's life, criticizing his Romish tendencies.[5]

Complaints of "ritualistic practices"

In 1888, a complaint by a churchwarden from Cleethorpes, funded by the Church Association, concerning a service conducted at St Peter at Gowts church in Lincoln, was brought against King. He stood accused of tolerating six ritualistic practices.[6] To avoid King's prosecution in a lay court under the Public Worship Regulation Act 1874, Benson revived his own archiepiscopal court (inactive since 1699).[7] In his "Lincoln Judgment", he found against King on two counts and also required him to conduct the manual acts during the prayer of consecration in the service of Holy Communion in such a way that the people could see them.[8] Benson specifically allowed the use of lighted candles, and mixing of elements, as well as the eastward position during the service.

The Church Association appealed against the ruling to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, but was denied in 1890.[9] King loyally conformed his practices to the archbishop's judgment.[1] Some considered the process a repudiation of the anti-ritualism movement,[10] though it proved physically and emotionally taxing for King, whose physique had never been particularly robust.

A decade later, after Frederick Temple succeeded Benson (1883–1896) as Archbishop of Canterbury, he and William Maclagan, Archbishop of York, prosecuted two priests for using incense and candles, and notified King of their condemnation, which he abided.[11] Later, many of King's liturgical practices became commonplace, including making the sign of the cross during the absolution and blessing, and mixture of elements during the service, for which the criticisms had been upheld as an innovation.

The Lincoln Judgment had a permanent importance in two respects. First, certain disputed questions of ritual were legally decided. Secondly, the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Canterbury alone to try one of his suffragan bishops for alleged ecclesiastical offences was considered and judicially declared to be well founded both by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council and by the Archbishop himself with the concurrence of his assessors.[12]

King's pastoral work as Bishop

As bishop, King devoted himself to pastoral work in his diocese, particularly among the poor, both farmers and industrial workers, as well as condemned prisoners. He supported the Guild of Railway men as well as chaplains in the Boer War and missionaries. In 1909 he visited Oxford in his episcopal capacity for the 400th anniversary of Brasenose College.[13]

Death and legacy

King died in Lincoln as Matins sounded on 8 March 1910 and was interred in the cathedral's cloister.

The calendar of the Church of England remembers King with the status of a "lesser festival" or "black letter day" on 8 March, the date of his death.

In 1913 a lady chapel was erected in King's memory at St Clement's Church, Leigh-on-Sea, by his nephew, Rev. Canon Robert Stuart King.[14]

In 2010 Rowan Williams, Archbishop of Canterbury, scheduled an episcopal visit to Lincoln to commemorate the 100th anniversary of King's death. In addition to citing King's contributions to pastoral theology and reinvention of episcopal practices, in an interview with the local church paper Williams called the former prosecution an embarrassment to the church and the state.[15]

References

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "King, Edward". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 803.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "King, Edward". Encyclopædia Britannica. 15 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 803. - George William Erskine Russell, Edward King, Sixtieth Bishop of Lincoln: A Memoir, Longman-Green: London, 1912, p. 69.

- Chisholm 1911.

- Russell, pp. 103-104

- Russell pp. 143-144.

- Russell, pp. 146-147, p. 166 et seq.

- Owen Chadwick, The Victorian Church, Part 2, Adam & Charles Black: place, 1980, p. 354.

- Russell, pp. 180-181

- Will Adam, Legal Flexibility and the Mission of the Church: Dispensation and Economy in Ecclesiastical Law (Ashgate Publishing 2013) at Google books

- Gerald Parsons, James Richard Moore (eds.), Religion in Victorian Britain: Traditions, Manchester University Press, 1988, p. 56.

- Russell, pp. 249-250.

-

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lincoln Judgment, The". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 712.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lincoln Judgment, The". Encyclopædia Britannica. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 712. - Russell, pp. 276-

- Historic England listing, "Grade II* listed buildings, St Clement Church, Leigh-on-Sea. Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Archbishop of Canterbury website. Rowan Williams, "Bishop of the Poor: Edward King reinvented the role of diocesan bishop", 5 March 2010.

External links

| Church of England titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Christopher Wordsworth |

Bishop of Lincoln 1885–1910 |

Succeeded by Edward Hicks |