Effects of Hurricane Floyd in Florida

Hurricane Floyd in 1999 threatened Florida as a major hurricane roughly three times as large as Hurricane Andrew.[nb 1] Floyd originated from a tropical wave well east of the Lesser Antilles on September 7. While approaching the Bahamas, the storm strengthened significantly between September 12 and September 13. On the latter day, Floyd peaked as a strong Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale. However, upon moving closer to the Bahamas, the storm fluctuated in intensity between a Category 3 and a Category 4 hurricane. A subtropical ridge eroded by a mid- to upper-tropospheric trough over the eastern United States caused Floyd to curve northwestward over the Abaco Islands and later to northeast, avoiding a potentially catastrophic landfall in Florida. The storm made its closest approach to Florida early on September 15, passing about 110 mi (180 km) east of Cape Canaveral.

| Tropical Storm (SSHWS/NWS) | |

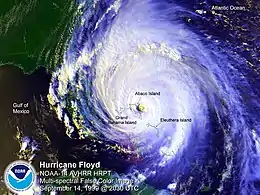

Hurricane Floyd over the Abaco Islands on September 14 | |

| Formed | September 13, 1999 |

|---|---|

| Dissipated | September 16, 1999 |

| Highest winds | 1-minute sustained: 55 mph (90 km/h) Gusts: 70 mph (110 km/h) |

| Lowest pressure | 989 mbar (hPa); 29.21 inHg |

| Damage | $50 million (1999 USD) |

| Areas affected | Florida |

| Part of the 1999 Atlantic hurricane season | |

Officials and residents in the state underwent extensive preparations due to the overwhelming threat from Floyd. Tropical cyclone warnings and watches were issued, including a hurricane warning from Florida City northward – nearly the entire east coast of Florida. Almost 1.37 million Floridians were placed under a mandatory evacuation order, while approximately 2.2 million people evacuated. At least 17 counties opened shelters, which collectively housed more than 53,498 people. Thousands of travelers were left stranded after airline companies canceled flights to and from Fort Lauderdale, Jacksonville, Miami, Orlando, and West Palm Beach. Walt Disney World closed for a full day for the first time since its opening in 1971.

Ultimately, Floyd remained well offshore and thus wrought relatively minor impacts in Florida. The hurricane produced sustained winds up to 56 mph (90 km/h) and gusts up to 69 mph (111 km/h). Beach erosion affected much of the state's Atlantic coast, though the worst impacts from Floyd occurred in Brevard and Volusia counties. In both counties, erosion left some structural damage. In the latter, winds and falling trees damaged a total of 337 homes. Volusia County alone experienced about $42 million in damage. Throughout Florida, damaged totaled about $50 million (1999 USD).[nb 2]

Background

A tropical wave exited the west coast of Africa on September 2. After moving generally westward for five days, a tropical depression developed well west of the Lesser Antilles on September 7. Early on the next day, the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Floyd. The cyclone reached hurricane intensity on September 9. While approaching the Bahamas, Floyd strengthened significantly between September 12 and September 13. On the latter day, the system peaked as a strong Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale with maximum sustained winds of 155 mph (250 km/h). However, upon moving closer to the Bahamas, the storm fluctuated in intensity between a Category 3 and a Category 4 hurricane. Although Floyd appeared to pose a significant threat to Florida, a subtropical ridge eroded by a mid- to upper-tropospheric trough over the eastern United States caused the storm to curve northwestward over the Abaco Islands and later to northeast. As a result, the storm made its closest approach to around 09:00 UTC on September 15, passing about 110 mi (180 km) east of Cape Canaveral. Floyd went on to make landfall in North Carolina on September 16 as a Category 2 hurricane and continued moving across the Mid-Atlantic and New England, before becoming extratropical just offshore Maine on September 17.[2]

Several hurricanes made landfall in Florida during the 1990s, including Andrew in 1992; Erin and Opal in 1995; and Earl and Georges in 1998. Another hurricane, Irene, would strike the state in October 1999, bringing the total to six.[3] However, Floyd was approximately three times larger than Andrew and similar in intensity.[4][5] At its peak intensity, tropical storm-force winds spanned a diameter of 580 mi (930 km), making Floyd one of the largest Atlantic hurricanes of its intensity ever recorded.[6] Several computer forecast models as late as September 13 predicted either a landfall in Florida or a glancing blow.[7] At the time, the forecast models errors for 48-hour positions averaged 40 mi (65 km) west of the storm's actual path.[8] The official forecasts from the National Hurricane Center, which made about average errors, outperformed all guidance models except for the UKMI model.[2]

Preparations

Initial fears were of a direct hit as a large Category 4 hurricane in Florida, potentially costlier and deadlier than Hurricane Andrew had been in 1992. As a result, the National Hurricane Center issued tropical cyclone warnings and watches along the Atlantic coast of Florida, beginning with a hurricane watch from Flagler Beach to Hallandale Beach at 09:00 UTC on September 13. Six hours later, the watch was extended northward to Brunswick, Georgia, and southward to Miami-Dade County. At 18:00 UTC, Lake Okeechobee was included in the watch area. Nearly the entire east coast of Florida was placed under a hurricane warning at 21:00 UTC on September 13, when the watch was upgraded from south of Brunswick to Florida City. Finally, a tropical storm warning was issued in the Florida Keys for areas north of the Seven Mile Bridge.[2]

In preparation for a potentially catastrophic landfall, Florida governor Jeb Bush declared a state of emergency on September 13.[9] As part of the declaration, 1,600 Florida National Guard troops were deployed in three battalions to posts in Miami, Orlando, and Palatka; 1,740 state troopers were assigned to major evacuation routes; tolls were lifted on Florida's Turnpike; and the Florida Department of Transportation managed traffic flow and assisted stranded motorists by supplying them with gasoline at rest stops. The Florida Department of Health deployed 400 employees to assistance staff at special needs shelters in 39 counties, while the Agency for Health Care Administration helped evacuate thousands of elderly and disabled residents from hospitals, nursing houses, and other assisted living institutes. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection closed 30 state parks and evacuated hundreds of campers.[10] United States President Bill Clinton also declared a federal state of emergency in Florida in anticipation of the storm's approach.[11]

Nearly 1.37 million Florida residents were told to evacuate, including approximately 272,000 in Miami-Dade, 206,000 in Palm Beach, 192,000 in Brevard, 116,000 in Broward, 114,000 in Volusia, 97,000 in St. Lucie and Duval, 69,000 in Martin, 60,000 in Monroe, 47,000 in Indian River, 29,000 in St. Johns, and 24,000 in Nassau and Flagler counties.[12] However, about 2.2 million Floridians evacuated, a significant cause for major traffic jams.[13] At the time, this was the largest evacuation in the state's history, until Hurricane Irma in 2017.[14] As the storm turned to the north, more people were evacuated as a progressively larger area was threatened. The massive storm caused what was at the time the largest peacetime evacuation ever in the United States, with an overall number of 2.6 million people evacuating coastal areas in Florida, Georgia, and the Carolinas.[15]

By September 12, the Red Cross was prepared to open eleven shelters in Palm Beach County and four in Martin County, which would shelter up to 4,000 people.[16] Overall, at least 53,498 stayed at shelters in 17 counties. Miami-Dade County had the most shelters and the highest number of shelter refugees, with 12,001 people staying at 30 shelters.[17] In Palm Beach County, the 11 shelters were only able to collectively accommodate 4,475 people, though roughly 5,300 people went to a shelter in the county. As a result, Broward County assisted with overflow issues.[12]

The Backstreet Boys postponed their Into the Millennium Tour concert at the BB&T Center (then known as the National Car Rental Center) in Sunrise on September 14 and September 15 to December 5 and December 6.[18] Walt Disney World was closed on September 14 and September 15, marking the first time it had closed for a full day since its opening in 1971. However, around 12:00 p.m. Eastern Standard Time (16:00 UTC) on September 15, the Animal Kingdom park was opened to resort guests.[19] There have since been four other times that Disney World closed for a full day – hurricanes Frances and Jeanne in 2004, Matthew in 2016, and Irma in 2017.[20] Several other Central Florida attractions and theme parks were closed, including the Bok Tower Gardens, Cypress Gardens, Fantasy of Flight, SeaWorld, and Universal Studios, which was closed for the first time since its opening in 1990.[19]

With the storm predicted to hit near Cape Canaveral with winds of over 140 mph (230 km/h), all but 80 of the Kennedy Space Center's 12,500-person workforce were evacuated. The hangars that house three space shuttles can withstand winds of only 105 mph (169 km/h), and a direct hit could have resulted in potentially billions of dollars in damage of space equipment, draining funds of an already money-strained government agency.[21] In the theoretical scenario, the damage would be caused by water, always a potential problem in an area only nine feet above sea level. If water entered the facility, it would damage the electronics as well as requiring a complete inspection of all hardware.[22] When Floyd actually passed by the area, Kennedy Space Center only reported light winds with minor water intrusion. Damage was minor overall, and was repaired easily.[23]

Because the Fort Lauderdale–Hollywood and Miami international airports were closed, the Miami Dolphins flew to the Southwest Florida International Airport in Fort Myers on a return trip from a game against the Denver Broncos. The Dolphins players were then bused to the training facility at Nova Southeastern University in Davie.[24] The Orlando and Palm Beach international airports were also closed. Additionally, airlines also canceled flights to and from Jacksonville International Airport. American Airlines alone canceled almost 600 flights to and from the Miami International Airport.[25]

Many schools, both public and private, were closed in several counties, including in Brevard, Broward, Clay, Flagler, Glades,[26] Hillsborough,[27] Indian River, Marion, Martin, Miami-Dade, Orange, Osceola,[26] Palm Beach, Pasco, Polk,[27] St. Johns, St. Lucie, and Volusia.[26] A number of colleges and universities also closed, including Bethune–Cookman University, Brevard Community College, Daytona Beach Community College,[28] Florida Atlantic University,[29] Florida International University,[26] Florida Southern College, Hillsborough Community College,[27] Indian River Community College,[30] Jacksonville University,[26] Northwood University, Palm Beach Atlantic University, Palm Beach State College,[29] Rollins College, Seminole Community College, Stetson University, University of Central Florida,[28] University of Florida, University of Miami, University of North Florida,[26] University of South Florida,[27] and Valencia Community College.[28]

Impact

Impact in South Florida was mostly minor. In Palm Beach County, a sustained wind speed of 37 mph (60 km/h) and a gust up to 56 mph (90 km/h) was observed at the pier in Lake Worth, while most areas experienced sustained winds of 25 to 30 mph (40 to 48 km/h). Light damage to trees and power lines was reported. Storm surge, reaching 3.3 ft (1.0 m) in Palm Beach County, left most minor beach erosion. Some areas reported moderate to heavy beach erosion, especially locations that already experienced erosion during Hurricane Dennis. The rough surf also damaged some sea walls and small boats. A tornado touched down in Boca Raton, but caused no damage. In Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties, damage reached only about $100,000.[31]

In the Treasure Coast – Martin, St. Lucie, and Indian River counties – about 25,000 homes lost electricity, according to Florida Power & Light. Additionally, around 12,000 households subscribed to the Fort Pierce Power Authority lost electricity, but much of the outages were restored in under an hour. Wind damage in this region was mainly limited to downed tree limbs and palm fronds. One home in Fort Pierce was destroyed by fire. Along the Indian and St. Lucie rivers, many docks were destroyed or lost boards, including at a House of Refuge on the Indian River. The three counties lost an average of 20 percent of sand.[32] In Lakeland, winds toppled a few large trees and power lines, while a mobile home was deroofed.[31]

Brevard County observed the strongest wind speed in the state, 56 mph (90 km/h) at Patrick Air Force Base.[2] Erosion and winds in the county severely damaged a few beachfront homes, while wind-driven rain resulted in minor roof or structural damage to some oceanfront hotels and swellings. At the Banana River and Indian River lagoons, erosion was also reported, along with the loss of private boating piers.[31] A total of 15 dune crossovers and possibly as many as 1,000 sea turtle nests were destroyed at the Canaveral National Seashore, with the park suffering about $480,000 in damage. Brevard County experienced its worst erosion since the November 1984 nor'easter.[33] Hundreds of trees fell, leaving about 55,000 homes without electricity across the county.[31] A total of nine homes in the county suffered major damage, including two house fires in Melbourne.[33] Damage in the county reached about $4.5 million, about half of which was caused by beach erosion.[31]

Farther north, Volusia County recorded the highest wind gust associated with Floyd in Florida, reaching 69 mph (111 km/h) in Daytona Beach.[2] These winds, along with falling trees, damaged a total of 337 homes. Extensive beach erosion occurred, with nearly all of the sand dunes washed away.[31] The Main Street pier and restaurant lost a section of about 200 ft (61 m). Approximately 100,000 businesses and homes in the county lost power.[12] Damage in the county reached nearly $42 million, which $10 million in damage caused by beach erosion.[31] The highest wind speed in Orange and Seminole counties was 48 mph (77 km/h), though stronger winds likely occurred. Power lines and trees were downed, mainly old oak and pine trees. Nineteen homes in the two counties suffered minor damage.[34] In Flagler County, abnormally high tides and erosion caused a 75 ft (23 m) section of the Flagler Beach pier to collapse and left portions of State Road A1A impassable,[12] especially at Flagler Beach and Marineland.[35]

Wind gusts peaked at 67 mph (108 km/h) in St. Johns County. Many large trees and power lines fell throughout the county. Winds damaged 30 homes, while 10 hotels were deroofed. Portions of the county received 6 to 8 in (150 to 200 mm) of rainfall.[31] Storm surge and rainfall flooded streets in the historical areas of St. Augustine, but caused little structural damage.[36] Extensive erosion occurred along the coast. Damage in St. Johns County totaled about $3 million. In Duval County, winds and falling trees inflicted major damage to three homes and minor damage to five others. The hurricane caused major erosion, including the destruction of over 100 ft (30 m) of the Jacksonville Beach pier. The storm left about $1 million in damage in Duval County. Farther north, over 50 homes were damaged, while one business experienced roof damage in Nassau County. About 3 to 4 ft (0.91 to 1.22 m) of sand was deposited onto County Road 105 in Fernandina Beach. Nassau County suffered about $2.5 million in damage.[31] Throughout Florida, Floyd caused about $50 million in damage.[37]

Aftermath

On September 14, President of the United States Bill Clinton approved a major disaster declaration for Brevard, Broward, Duval, Flagler, Indian River, Martin, Nassau, Palm Beach, St. Johns, St. Lucie, and Volusia counties.[38] Through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, the federal government offered up to 75% reimbursement for damages to public facilities in those counties.[39] A study conducted after the storm indicated that 62 out of 67 counties lacked adequate shelter space in the event of a worst-case scenario hurricane. Therefore, Governor Jeb Bush proposed that $18 million to be allocated in the 2000 state budget to create new shelters and improve those already existing, with the money coming from federal, state, and local sources. Plans called for shelter space to collectively accommodate an additional 88,679 people.[40]

Approximately 2.2 million people in Florida evacuated,[13] although only about 1.37 million were ordered to,[12] a large contributing factor to major traffic jams. Most of those ordered to evacuate lived along the coast, in mobile homes, or in low-lying areas. However, in coastal Central Florida counties, for instance, a 2,400-person telephone survey indicated that approximately 40% of residents in inland areas evacuated even though they faced little danger. As a result, state officials and emergency management recommended that non-vulnerable residents remain at home or close to home during future hurricanes. Officials also suggested contraflow lane reversal on the interstate highways and Florida's Turnpike. Another recommendation to improve disaster preparation was to provide better and further up-to-date information on FloridaDisaster.org – the official website of the Florida Division of Emergency Management – about preparations, evacuations, shelters, and traffic conditions along evacuation routes.[13]

See also

Notes

- A major hurricane is a storm that ranks as Category 3 or higher on the Saffir–Simpson hurricane wind scale.[1]

- All damage figures are in 1999 USD, unless otherwise noted

References

- Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. National Hurricane Center (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 23, 2013. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Richard J. Pasch; Todd B. Kimberlain; Stacy R. Stewart (September 9, 2014). Preliminary Report Hurricane Floyd (PDF) (Report). National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- Continental United States Hurricane Impacts/Landfalls 1851-2017. Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (Report). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- Athena Damianos (September 14, 1999). "Hurricane Floyd roars over Bahamas, toward Florida". ReliefWeb. Reuters. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- Climate-Watch, September 1999 (Report). National Climatic Data Center. March 2, 2000. Archived from the original on January 3, 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- David Herring (2000). "Hurricane Floyd's Lasting Legacy". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- John L. Guiney (September 13, 1999). "Hurricane Floyd Discussion Number 23". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- S. G. Gopalakrishnan; et al. (July 2002). "An Operational Multiscale Hurricane Forecasting System" (PDF). Monthly Weather Review. Center for Atmospheric Physics, Science Applications International Corporation: 1830. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(2002)130<1830:AOMHFS>2.0.CO;2. Retrieved May 14, 2019.

- Mary McLachlin (September 14, 1999). "Floyd 'controls its own destiny'". The Palm Beach Post. p. 13A. Retrieved May 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Jim Ash; Marjorie Menzel (September 16, 1999). "State had quick response to Floyd". News-Press. p. 10. Retrieved May 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Floyd keeps US guessing". BBC News. September 15, 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- "Floyd's coastal impact". The Orlando Sentinel. September 16, 1999. p. A-13. Retrieved May 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Alisa LaPolt (August 19, 2000). "Latest hurricane warning: Stay home". Florida Today. p. 2B. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane Irma – Evacuation". Florida Association of Counties. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- National Climatic Data Center (1999). "Climate-Watch, September 1999". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on October 24, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- Sanjay Bhatt and Larry Hobbs (September 12, 1999). "Fringes could affect S. Florida by Monday". The Palm Beach Post. p. 13A. Retrieved May 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hurricane Floyd Assessment: Review of Hurricane Evacuation Studies Utilization and Information Dissemination (PDF) (Report). United States Army Corps of Engineers and Federal Emergency Management Agency. May 2000. p. 4-2 – 4-4. Retrieved May 3, 2019.

- "Backstreet Boys don't want it this way". The Palm Beach Post. September 14, 1999. p. 13A. Retrieved March 31, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kevin Bouffard (September 15, 1999). "Disney Set For 1st Storm Closing". The Ledger. Lakeland, Florida. p. A6. – via NewsBank (subscription required)

- Stephanie Toone (September 12, 2017). "Disney World, Universal Studios miss brunt of Irma; will reopen Tuesday". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- Kenneth Silber (1999). "Bracing for Impact". Space.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2001. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- Jonathan Lipman (1999). "Storm May Further Jeopardize NASA Budget". Space.com. Archived from the original on October 12, 1999. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- Kenneth Silber (1999). "NASA Reports 'Minor' Damage at Space Center". Space.com. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- Rick Weber (September 15, 1999). "Dolphins land here, take buses to Miami". News-Press. p. 9A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Airport closings strand thousands". News-Press. September 15, 1999. p. 9A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Closings". Pensacola News Journal. September 14, 1999. p. 2A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Closings". The Tampa Tribune. September 15, 1999. p. 7. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "School closings". The Orlando Sentinel. September 14, 1999. p. 13A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Palm Beach County closings". The Palm Beach Post. September 14, 1999. p. 13A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Treasure Coasts closings, reschedulings". The Palm Beach Post. September 14, 1999. p. 13A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Storm Data and Unusual Weather Phenomena with Late Reports and Corrections" (PDF). National Climatic Data Center. Asheville, North Carolina: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 41 (9). ISSN 0039-1972. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 11, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- "Beaches erode, electricity lost in storm". The Palm Beach Post. September 16, 1999. p. 12A. Retrieved May 4, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Erosion toll on beaches costly". Florida Today. September 18, 1999. p. 2. Retrieved May 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- Hurricane Floyd East Central Florida Summary September 14-15, 1999 (PDF) (Report). National Weather Service Melbourne, Florida. 1999. p. 3. Retrieved May 6, 2019.

- Roger Roy; E. Garrett Youngblood (September 16, 1999). "Floyd giveth, taketh away – sand". Orlando Sentinel. p. A-13. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- David Royse (September 16, 1999). "Oldest city protected from hurricanes". Tallahassee Democrat. Associated Press. p. 10A. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- David Sedore (September 25, 1999). "Floyd's damage to Florida: $50 million". The Palm Beach Post. p. 1B. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Designated Areas: Disaster 3143". Federal Emergency Management Agency. 1999. Retrieved May 5, 2019.

- Lynn Bumpus-Hooper (September 25, 1999). "Hurricane Floyd-related disaster-relief money could be on the way". Orlando Sentinel. p. 1-D. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Hurricane". Tallahassee Democrat. April 4, 2000. p. 2A. Retrieved May 5, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.