El-Buss refugee camp

El-Buss camp (Arabic: مخيم البص) – also transliterated Bass, Bas, or Baas with either the article Al or El respectively – is one of the twelve Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon, located in the Southern Lebanese city of Tyre. It had been a refuge for survivors of the Armenian Genocide from the 1930s until the 1950s, built in a swamp area which during ancient times had for at least one and a half millennia been a necropolis. In recent decades it has been "at the center of Tyre’s experience with precarity" and "a space that feels permanent yet unfinished, suspended in time."[1]

El-Buss camp

مخيم البص | |

|---|---|

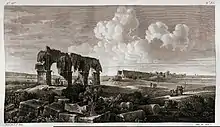

Remains of a Roman aquaeduct in El Buss with the camp in the background | |

| |

El-Buss camp | |

| Coordinates: 33°16′21″N 35°12′36″E | |

| Country | |

| Governorate | South |

| District | Tyre |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1 km2 (0.4 sq mi) |

| Population | 11,254 |

Territory

El Buss is located in the North-Eastern part of the Sour municipality. While Tyre as a whole is commonly known as Sour in Arabic, its urban area comprises parts of four municipalities: Sour, Ain Baal, Abbassieh and Burj El Chamali. The two latter ones are close to El-Buss. Burj El Shimali, about 2 km to the East of El-Buss also hosts a Palestinian refugee camp, while the gathering of Jal Al Baher to the North and the neighbourhood of Maashouk 1 km to the East are informal settlements for Palestinian refugees.[2] To the South of El Buss camp - separated through a wall and the remaining water pools of the original marshland - is the vast archaeological site of El-Buss, which is popular with tourists.

The camp covers a total area of approximately 1 square kilometer.[3] At its Northern side the camp borders the main roads at the entry to the Tyre peninsula and to its Eastern side the North-South Beirut-Naqoura Sea Road. Hence, it is severely affected by heavy traffic jams at the crossroads, especially during peak hours at the El Buss roundabout.[2] The camp has a number of entrances for pedestrians, but only one - on the South-Eastern side - for vehicles. Entry and exit there is controlled at a checkpoint by the Lebanese Armed Forces.[1] Foreign visitors have to present permits from Military Intelligence to them.[4]

"although it is a labyrinth of tiny alleys crisscrossing each other haphazardly, it is much less crowded and daunting than some of the other camps across the country."[3]

A 2017 census counted 687 buildings with 1,356 households in el-Buss.[5] Most of the buildings are concrete block shelters, considered to be of poor quality.[2] While the building situation in the eastern part around the former Armenian camp is dense, the western part of the camp has developed in a more informal manner.[6] The many businesses, especially mechanical workshops for cars, on the Northern side along the main road integrate the outer fringe of the camp into the townscape.[6] However,

"Though very much a part of the city’s urban fabric, El-Buss remains a peripheral space".[1]

And as Tyre like all of Southern Lebanon has been marginalised throughout modern history, El Buss camp is actually even

"peripheral within the periphery".[1]

History

Phoenician times

El Buss refugee camp is located in a historical site that dates back at least three thousand years. A Phoenician cremation cemetery from the Iron Age was uncovered in an area of some 500 square meters in the southeastern corner of the camp, the first discovery of its kind[7] and with about 320 excavated urns the most densely occupied Phoenician cemetery known in the Levant. El Buss was the principal graveyard for the maritime merchant-republic city-state of Tyre in its most expansive and prosperous era for almost four hundred years.[8] It thus offers unique windows into the Phoenician past:[9]

The cemetery was established at the end of the tenth century BCE on what was then a sea-beach at the edge of the coast opposite of what was then the island city of Tyre. The beach originally also bordered the southern edge of an ancient creek delta.[8] The landscape shifted though over the centuries and millennia. Hence, the creek bay turned into a lagoon, separated from the sea by a sand bar:[9]

"Paleobotanical and faunal analyses of the sand sediment in the area show that the creek became a lake during the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E."[8]

The most common type of burial in this necropolis was made up of twin-urns with the remains of the same individual - one containing the ashes and the other the bones mixed personal possessions, as well as two jugs and a bowl for drinking. About a fifth of the discovered urns with bone remains contained a scarab-amulet. The researchers, led by Professor María Eugenia Aubet from the Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, also excavated a few stelae which bore inscriptions and human masks sculpted from terracotta.[8] Some of them are considered to be masterpieces and on display at the National Museum of Beirut.[10] Altogether, one has to imagine a beach with such personalised gravestones sticking out of the sand, with a view on the fortified island city. Aubet concludes:

"The structure of the cemetery at Tyre is in some ways reminiscent of the European urnfields, in which apparently little formal differentiation according to the sex, age, and content of the burials can be seen, although their structure in fact conceals genuine social asymmetries. [..] Rather than an 'egalitarian' society for Tyre, we should probably speak of an egalitarian ideology, appropriate to a wholly urban and sophisticated society, characterized by the relative simplicity and lack of ostentation of its funeral customs. A communal ideology that concealed differences of wealth and power is evident. [..] with only limited evidence of social stratification, such a conclusion should be regarded as tentative and subject to refinement on the basis of further and future excavations at Tyre."[8]

Hellenistic times

In 332 BCE, Alexander the Great had an isthmus of about 1.000 meters length constructed in 332 BCE to breach the fortifications of offshore-Tyre. This causeway increased greatly in width because of extensive silt depositions on either side over the centuries. The growing tombolo linked the original island permanently to the adjacent continent and made the city a peninsula.[11] As a consequence of this man-made metamorphosis of the Tyrian coastal system, the Phoenician graves in El Buss were buried under sediments of clay and sand. After almost two and a half millennia, they are now at more than 3.5 m under the ground level of El Buss.[8]

Before the landscape changed though, the Phoenician funerary site of El Buss was still used during the Hellenistic era.[8] In addition, the area just neighbouring to the North, now known as Jal Al Bahr, became a burial ground, as recent excavations have shown.[12] To the South of it, a sanctuary dedicated to the Olympian deity of Apollo was constructed, possibly still at the end of the Hellenistic era[10] or latest in the first century CE:[13]

Roman times

In 64 BCE the area of "Syria" finally became a province of the late Roman Republic, which was itself about to become the Roman Empire. Tyre was allowed to keep much of its independence as a "civitas foederata".

Various sources in the New Testament state that Jesus visited Tyre (Gospel of Luke 6:17; Mark 3:8 and 7:24; Matthew 11:21–23 and 15:21).[14] According to many believers in later centuries, he sat down on a rock in the Southern part of El Buss and had a meal there.[10] Scientific analyses from archaeological excavations indicate that an olive grove planted was inside the Roman necropolis at the beginning of the Christian era.[8]

In the early second century CE, Emperor Hadrian, who visited the cities of the East around 130 CE, conferred the title of Metropolis on Tyre: "great city" mother of other cities.[14] Subsequently, a triple-bay Triumphal Arch, an aqueduct from the springs of Ras al-Ain some six kilometers to the South and the Tyre Hippodrome were constructed. The arch was 21 meters high and became the gateway of the Roman town. At its side pillars were erected that were more than four meters high and carried the water canal alongside the road into the town on the peninsula.[15] The hippodrome is the largest (480m long and 160m wide) and best-preserved Roman hippodrome after the one in Rome.[16] The amphitheater for the horse-racetrack could host some 30.000 spectators. During the third century CE, the Heraclia games – dedicated to the deity Melqart-Heracles (not to be confused with the demigod Heracles, hero of the 12 labors) – were held in the hippodrome every four years.[14]

Meanwhile, between the first and fourth centuries CE, one of the largest known cemeteries of the region grew in El Buss with more than forty tomb complexes, at least 825 graves and the physical remains of almost 4,000 individuals.[15] The marble sarcophagi, which were imported from Greece and Asia Minor, and the other tombs of the monumental necropolis spread on both sides of the road leading to the triumphal arch over a kilometer in length.[16] It is unclear how far the burial grounds extended, but researchers argue that large parts of the modern camp could well have been part of the necropolis. Whereas the Phoenician funeral practices of an egalitarian ideology concealed social differences, the Roman graves did the opposite:

"The tombs of Tyre [..] demonstrate that the coming of Rome was not just a new economic and military reality but also caused social and cultural changes, which were acted out in part in the cemetery. [..] Through the display of socioeconomic position and civic and group identity, the tombs played an important and new role in the definition of social groups, and perhaps in the renegotiation of the boundaries of these groups.[15]

Byzantine period (395–640)

In 395 Tyre became part of the Byzantine Empire and continued to flourish. Likewise, the necropolis in El Bus grew further to be arguably one of the largest in the world, though many graves were "reused".[15] A main road of some 400m length and 4,5m width paved with limestone was constructed there during Byzantine times.[17] Another arch, smaller than the Roman triumphal arch, was erected some 315 meters to the East.[15]

At the entrance to the oldest monument in the El Buss site - the Apollo Shrine from the 1st century BCE - a fresco was found that has been dated to 440 CE and is "possibly the earliest image of the Virgin Mary" worldwide.[10] Close by, two churches with marble decorations were built in the 5th and early 6th century CE respectively, when construction in ancient Tyre reached its zenith.[10]

Over the course of the 6th century CE, starting in 502, a series of earthquakes shattered the city and left it diminished. The worst one was the 551 Beirut earthquake. It was accompanied by a Tsunami and destroyed the Great Triumphal Arch in El Buss.[18] In addition, the city and its population increasingly suffered during the 6th century from the political chaos that ensued when the Byzantine empire was torn apart by wars. The city remained under Byzantine control until it was captured by the Sassanian shah Khosrow II at the turn from the 6th to the 7th century CE, and then briefly regained until the Muslim conquest of the Levant, when in 640 it was taken by the Arab forces of the Rashidun Caliphate.[19]

Early Muslim period (640–1124)

As the bearers of Islam restored peace and order, Tyre soon prospered again and continued to do so during half a millennium of Caliphate rule.[10] The Rashidun period only lasted until 661. It was followed by the Umayyad Caliphate (until 750) and the Abbasid Caliphate. In the course of the centuries, Islam spread and Arabic became the language of administration instead of Greek.[19]

Although some people reportedly continued to worship ancient cults,[20] the necropolis of El Buss and the other installations there were abandoned still in the 7th century CE and quickly covered by sand dunes.[15]

At the end of the 11th century, Tyre avoided being attacked by paying tribute to the Crusaders who marched on Jerusalem. However, in late 1111, King Baldwin I of Jerusalem laid siege on the former island city and probably occupied the mainland, including El Buss, for that purpose. Tyre in response put itself under the protection of the Seljuk military leader Toghtekin. Supported by Fatimid forces, he intervened and forced the Franks to raise the siege in April 1112, after about 2.000 of Baldwin's troops had been killed. A decade later, the Fatimids sold Tyre to Toghtekin who installed a garrison there.[14]

Crusader period (1124–1291)

On 7 July 1124, in the aftermath of the First Crusade, Tyre was the last city to be eventually conquered by the Christian warriors, a Frankish army on the coast - i.e. also in the El Buss area - and a fleet of the Venetian Crusade from the sea side. The takeover followed a siege of five and a half months that caused great suffering from hunger to the population.[14] Eventually, Tyre's Seljuk ruler Toghtekin negotiated an agreement for surrender with the authorities of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem.[21]

Under its new rulers, Tyre and its countryside - including El-Buss - were divided into three parts in accordance with the Pactum Warmundi: two-thirds to the royal domain of Baldwin and one third as autonomous trading colonies for the Italian merchant cities of Genoa, Pisa and - mainly to the Doge of Venice. He had a particular interest in supplying silica sands to the glassmakers of Venice[22] and so it may be assumed that El Buss fell into his interest sphere. It has to be assumed that at least the Southern part of El Buss was populated, since the Savior Church was built during the crusaders era in a place of the former hippodrome where Jesus supposedly sat down on a rock and had a meal. Hundreds of pilgrims left their signatures on its walls.[10]

Mamluk period (1291–1516)

In 1291, Tyre was again taken, this time by the Mamluk Sultanate's army of Al-Ashraf Khalil. He had all fortifications demolished to prevent the Franks from re-entrenching.[23] After Khalil's death in 1293 and political instability, Tyre lost its importance and "sank into obsurity." When the Moroccan explorer Ibn Batutah visited Tyre in 1355, he found it a mass of ruins.[14] Many stones were taken to neighbouring cities like Sidon, Acre, Beirut, and Jaffa[24] as building materials.[14] It may be assumed that this was true for the ancient ruins of El Buss, especially the Roman-Byzantine necropolis, aquaeduct and hippodrome as well, as far as they had not been buried underneath sand dunes already. The aquaeduct became the "lone witness to the city’s glorious past."[25]

Ottoman rule (1516-1918)

The Ottoman Empire conquered the Levant in 1516, yet Tyre remained untouched for another ninety years until the beginning of the 17th century, when the Ottoman leadership at the Sublime Porte appointed the Druze leader Fakhreddine II of the Maan family as Emir to administer Jabal Amel (modern-day South Lebanon) and Galilee in addition to the districts of Beirut and Sidon.[26] It is not known whether the area of El Buss was part of his development projects. However, as he encouraged Shiites and Christians to settle to the East of Tyre, Fakhreddine laid the foundation of modern Tyre demographics as many of those settlers – or their descendants respectively – later moved to the town, thus providing the socio-political context for the subsequent erection of El Buss camp.[27]

In 1764, the French geographer Jacques Nicolas Bellin published a map of Greater Tyre which included the ruins of the aquaeduct in El Buss, but no settlements.[28] Around 1786, Bellin's fellow countryman Louis-François Cassas visited the place and drew a painting of the ruins of the aquaeduct.[29]

In 1878, the London-based Palestine Exploration Fund's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) – led by Herbert Kitchener at the beginning of his military career – mapped Tyre and its surroundings. It described the area of Birket el Bass – north of the aquaeduct – as a "ruined birket" (water reservoir or pool) and as "dry." [30] A map from a 1906 Baedeker travel guide designated the area as a "Swamp" though.

French Mandate colonial rule (1920–1943)

_(14804481453)_cropped.jpg.webp)

On the first of September 1920, the French colonial rulers proclaimed the new State of Greater Lebanon under the guardianship of the League of Nations represented by France. Tyre and the Jabal Amel were attached as the Southern part of the Mandate. The French High Commissioner in Syria and Lebanon became General Henri Gouraud.[31]

In 1932, the colonial authorities offered a piece of land of some 30,000 square meters in El Buss to the Jabal Amel Ulama Society of Shia clerics and feudal landlords to construct a school there. However, such plans were not realised due to internal divisions of the local power players and a few years later the French rulers attributed the swampy area to survivors of the Armenian Genocide,[26] who had started arriving in Tyre already in the early 1920s,[32] mostly by boat.[33] A branch of the Armenian General Benevolent Union had been founded there in 1928.[32]

It is unclear when exactly the camp for Armenian refugees was set up. According to some sources it was in 1935–36,[34][35][36] when also another camp was built in Rashidieh on the coast, five kilometres south of Tyre city.[37] However, the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) states that El Buss camp was constructed in 1937,[38] whereas the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN HABITAT) dates it to 1939.[2]

During the following years - neither the exact dates are known nor the Christian denominations - an Armenian chapel and a church were constructed in El Buss camp. The defunct chapel is nowadays part of an UNRWA school building, while the church of Saint Paul belongs to the Maronite Catholic Archeparchy of Tyre and is still in service.[3][35]

On 8 June 1941, a joint British-Free French Syria–Lebanon campaign liberated Tyre from the Nazi-collaborators of Marshal Philippe Pétain's Vichy regime.[39]

Post-Independence (since 1943)

Lebanon gained independence from French colonial rule on 22 November 1943. The Maronite political leader Émile Eddé – a former Prime Minister and President – reportedly suggested to the Zionist leader Chaim Weizmann[40] that a Christian Lebanon

"should relinquish some portions of the no longer wanted territory, but to the Jewish state-in-the-making. It could have Tyre and Sidon and the 100,000 Muslims living there, but when he put the matter to Weizmann, even he balked at what he called a gift which bites'."[41]

1948/9 Palestinian exodous

When the state of Israel was declared in May 1948, Tyre was immediately affected: with the Palestinian exodus – also known as the Nakba' – thousands of Palestinian refugees fled to the city, often by boat.[26] El-Buss was one of the first sites which was assigned to the Palestinian refugees as a transit camp.[34][35] The majority of the first wave of Palestinians who arrived in El-Buss were Palestinian Christians from Haifa and Akka.[34] Most of them only found shelter in tents there.[42]

Soon the camp was overcrowded and more camps were set up in other parts of the country. Initially, Armenians and Palestinians cohabited in the camp.[35] In the course of the 1950s, the Armenian refugees from El Buss were resettled to the Anjar area, while Palestinians from the Acre area in Galilee moved into the camp.[38] Many of them were apparently agriculturalists. Before UNRWA opened its first school in El Buss, children received education under the roof of the church or chapel.[3]

In 1957, large-scale excavations of the Roman-Byzantine necropolis in El Buss started under the leadership of Emir Maurice Chéhab (1904-1994), "the father of modern Lebanese archaeology" who for decades headed the Antiquities Service in Lebanon and was the curator of the National Museum of Beirut. The works stopped in 1967 and because of the political turmoil that followed Chehab could not take them up again. Publication of his research materials was never completed either. The whereabouts of most of the finds and the excavation documentation are unknown.[15]

In 1965, residents of El Buss gained access to electricity.[3]

After the Six-Day War of June 1967 another wave of displaced Palestinians sought refuge in South Lebanon.[43] In the following year, El Buss camp had 3,911 registered inhabitants.[34] As Tyre greatly expanded during the 1960s due to an increasing a rural-to-urban movement and many new buildings were constructed on the isthmus of the peninsula,[2] El Buss became physically more integrated into the city.[3] The solidarity of the Lebanese Tyrians with the Palestinians was especially demonstrated in January 1969 through a general strike to demand the repulsion of Israeli attacks on Palestinian targets in Beirut.[44]

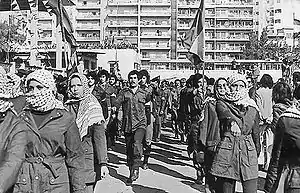

At the same time though, the arrival of civilian refugees went along with an increasingly strong presence of Palestinian Militants. Thus, clashes between Palestinians and Israel increased dramatically: On 12 May 1970, the IDF launched a number of attacks in South Lebanon, including Tyre. The Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon escalated further after the conflict of Black September 1970 between the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO).[26] The PLO leadership under Yasir Arafat relocated to Lebanon, where it essentially created a state within a state and recruited young fighters - known as fedayeen - in the refugee camps.[1]

The 1973 October Yom Kippur War signalled even more Palestinian military operations from Southern Lebanese territory, including Tyre, which in turn increasingly sparked Israeli retaliation.[26]

In the following year, the Iran-born Shiite cleric Sayed Musa Sadr who had become the Shia Imam of Tyre in 1959, founded Harakat al-Mahroumin ("Movement of the Deprived") and one year later – shortly before the beginning of the Lebanese Civil War – its de facto military wing: Afwaj al-Muqawama al-Lubnaniyya (Amal).[45] Military training and weaponry for its fighters was initially provided by Arafat's PLO-faction Fatah, but Sadr increasingly distanced himself from them as the situation escalated into a civil war:[46]

Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990)

In January 1975, a unit of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) attacked the Tyre barracks of the Lebanese Army.[27] The assault was denounced by the PLO as "a premeditated and reckless act".[44] However, two months later, a PLO commando of eight militants sailed from the coast of Tyre to Tel Aviv to mount the Savoy Hotel attack, during which eight civilian Hostages and three Israeli soldiers were killed as well as seven of the attackers.[47] Israel retaliated by launching a string of attacks on Tyre "from land, sea and air" in August and September 1975.[48]

Then, in 1976, local commanders of the PLO took over the municipal government of Tyre with support from their allies of the Lebanese Arab Army.[44] They occupied the army barracks, set up roadblocks and started collecting customs at the port. However, the new rulers quickly lost support from the Lebanese-Tyrian population because of their "arbitrary and often brutal behavior".[49]

By 1977, the UNRWA census put the population of El Buss camp at 4,643.[34] As their situation deteriorated, emigration to Europe increased. At first, a group of graduates went to what was then West-Berlin, because entry via East-Berlin did not require travel visa. Many settled there or in what was then West-Germany:

"They concentrated on working in the catering and the construction sectors. They still, however, maintained close connections with their country of departure by sending money to their families remaining in Lebanon. When they acquired German citizenship or valid residence permits they were able to visit their families in Lebanon. Afterwards, as their savings grew, they were able to facilitate the arrival of close relatives (e.g., brother, parent, sister). In many cases, their integration into German society was further enhanced by marriage with Germans."[50]

At the same time, most of the Christian population gradually moved out of the camp.[35] Allegedly, many of them were granted Lebanese citizenship by the Maronite ruling class in a demographic attempt to compensate for the many Lebanese Christians who emigrated.[3]

In 1977, three Lebanese fishermen in Tyre lost their lives in an Israeli attack. Palestinian militants retaliated with rocket fire on the Israeli town of Nahariya, leaving three civilians dead. Israel in turn retaliated by killing "over a hundred" mainly Lebanese Shiite civilians in the Southern Lebanese countryside. Some sources reported that these lethal events took place in July,[41] whereas others dated them to November. According to the latter, the IDF also conducted heavy airstrikes as well as artillery and gunboat shelling on Tyre and surrounding villages, but especially on the Palestinian refugee camps in Rashidieh, Burj El Shimali and El Bass.[51]

1978 South Lebanon conflict with Israel

On 11 March 1978, Dalal Mughrabi – a young woman from the Palestinian refugee camp of Sabra in Beirut – and a dozen Palestinian fedayeen fighter sailed from Tyre to a beach north of Tel Aviv. Their attacks on civilian targets became known as the Coastal Road massacre that killed 38 Israeli civilians, including 13 children, and wounded 71.[41] According to the United Nations, the

PLO "claimed responsibility for that raid. In response, Israeli forces invaded Lebanon on the night of 14/15 March, and in a few days occupied the entire southern part of the country except for the city of Tyre and its surrounding area."[52]

Nevertheless, Tyre was badly affected in the fighting during the Operation Litani. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) targeted especially the harbour on claims that the PLO received arms from there and the Palestinian refugee camps.[53] El Buss suffered extensive damage from Israeli air and navy attacks.[34]

"On 15 March 1978, the Lebanese Government submitted a strong protest to the Security Council against the Israeli invasion, stating that it had no connection with the Palestinian commando operation. On 19 March, the Council adopted resolutions 425 (1978) and 426 (1978), in which it called upon Israel immediately to cease its military action and withdraw its forces from all Lebanese territory. It also decided on the immediate establishment of the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL). The first UNIFIL troops arrived in the area on 23 March 1978."[52]

However, the Palestinian forces were unwilling to give up their positions in and around Tyre. UNIFIL was unable to expel those militants and sustained heavy casualties. It therefore accepted an enclave of Palestinian fighters in its area of operation which was dubbed the "Tyre Pocket". In effect, the PLO kept ruling Tyre with its Lebanese allies of the National Lebanese Movement (NLM), which was in disarray though after the 1977 assassination of its leader Kamal Jumblatt.[27]

Frequent IDF bombardments of Tyre from ground, sea and air raids continued after 1978.[54] In January 1979, Israel started naval attacks on the city.[55] The PLO reportedly converted itself into a regular army by purchasing large weapon systems, including Soviet WWII-era T-34 tanks, which it deployed in the "Tyre Pocket" with an estimated 1,500 fighters.[27]

On the 27th April 1981, the Irish UNIFIL-soldier Kevin Joyce got kidnapped by a Palestinian faction from his observation post near the village of Dyar Ntar and, "according to UN intelligence reports, was taken to a Palestinian refugee camp in Tyre. He was shot dead a few weeks later following a gun battle between Palestinians and UN soldiers in south Lebanon."[56]

The PLO kept shelling into Galilee until a cease-fire in July 1981.[27] On the 23rd of that month, the IDF had bombed Tyre.[57]

As discontent within the Shiite population about the suffering from the conflict between Israel and the Palestinian factions grew, so did tensions between Amal and the Palestinian militants.[55] The power struggle was exacerbated by the fact that the PLO supported Saddam Hussein's camp during the Iraq-Iran-War, whereas Amal sided with Teheran.[1] Eventually, the political polarisation between the former allies escalated into violent clashes in many villages of Southern Lebanon, including the Tyre area.[55]

1982 Israeli invasion

Following an assassination attempt on Israeli ambassador Shlomo Argov in London the IDF started an invasion of Lebanon on 6 June 1982, which heavily afflicted Tyre once again: Shelling by Israeli artillery[58] and air raids killed some 80 people on the first day across the city.[59] The Palestinian camps were bearing the brunt of the assault, as many guerillas fought till the end.[41] Though El Buss was less affected than other camps, a contemporary United Nations report found that half of the houses in the camp were either badly damaged or destroyed during the invasion.[60][61] The Advisory Committee on Human Rights of the American Friends Service Committee termed the destruction of homes in El-Buss "systematic".[62] As a consequence, the drive to emigrate from El-Buss increased further:

"Some of the refugees, in particular those who were injured or whose dwellings were completely destroyed, sought to leave Lebanon indefinitely. Connection between internal migration and international migration was effected at that time. Denmark and Sweden agreed to accept these refugees. Germany too continued to receive some of them. The migratory field thus extended to new countries further north, whilst Germany, the previous principal recipient country, now became primarily a country of transit towards Scandinavia."[50]

In 1984, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) declared Tyre, including el Buss, a World Heritage Site in an attempt to halt the damage being done to the archaeological sites by the armed conflict and by anarchic urban development.

1985-1988 War of the Camps: Amal vs. PLO

Under the growing pressure of suicide attacks by Hezbollah, the Israeli forces withdrew from Tyre by the end of April 1985[27] and instead established a self-declared "Security Zone" in Southern Lebanon with its collaborating militia allies of the South Lebanon Army (SLA). Tyre was left outside the SLA control though[63] and taken over by the Amal Movement under the leadership of Nabih Berri:[46]

"The priority of Amal remained to prevent the return of any armed Palestinian presence to the South, primarily because this might provoke renewed Israeli intervention in recently evacuated areas. The approximately 60,000 Palestinian refugees in the camps around Tyre (al-Bass, Rashidiya, Burj al-Shimali) were cut off from the outside world, although Amal never succeeded in fully controlling the camps themselves. In the Sunni 'canton' of Sidon, the armed PLO returned in force."[27]

Tensions between Amal and Palestinian militants soon escalated once again and eventually exploded into the War of the Camps, which is considered as "one of the most brutal episodes in a brutal civil war":[64] In September 1986, a group of Palestinians fired on an Amal patrol at Rashidieh. After one month of siege, Amal attacked the refugee camp in the South of Tyre.[46] It was reportedly assisted by the Progressive Socialist Party of Druze leader Walid Jumblatt, whose father Kamal had entered into and then broken an alliance with Amal-founder Musa Sadr, as well as by the pro-Syrian Palestinian militia As-Saiqa and the "Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command".[65] Fighting spread and continued for one month. By that time some 7,000 refugees in the Tyre area were displaced once more:[46] On December 3, El Buss was taken over by Amal,[51] as it "overran the unarmed camps of El Buss and Burj el-Shemali, burning homes and taking more than a thousand men into custody."[66] At the same time, many Lebanese Shiite families who were displaced from the Israeli-occupied southern "security zone" started building an informal neighbourhood on the Western side next to the camp.[6] Meanwhile, emigration for Palestinians from El Bus to Europe became increasingly difficult, since favourite destinations like Germany and Scandinavia adopted more restrictive asylum policies:

"A transnational field emerged with the circulation of information, and, to a lesser extent, of people, between the Palestinians still residing in Al Buss and those of Europe."[50]

In the late 1980s, "clandestine excavations" took place in the Al-Bass cemetery which "flooded the antiquities market".[67] In 1990, a necropolis from the Iron Age was discovered in El Buss "by chance".[8]

Post-Civil War (since 1991)

Following the end of the war in March 1991 based on the Taif Agreement, units of the Lebanese Army deployed along the coastal highway and around the Palestinian refugee camps of Tyre, including El-Buss.[68]

The patterns of emigration changed through the 1990s, as European border regimes further tightened:

"The geographical extension of the migratory field widened and touched countries such as the United Kingdom and Belgium. The three principal host countries (Germany, Sweden, and Denmark) continued to play a central role in this migratory system, but increasingly as transit countries."[50]

At the end of the decade, UNRWA estimated the population to be 9,498.[35]

In 1997, Spanish-led archaeological excavations started at El-Buss. They were conducted for eleven years and exposed an area of some 500 square meter of cremation graves.[8]

In 2005 the Lebanese government abolished long-standing limitations for residents of El Buss to add a storey to their house. After the lifting of such spatial restrictions the camp witnessed a densification in its buildings.[6]

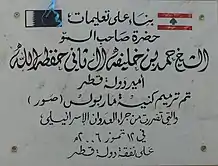

During Israel's invasion in the July 2006 Lebanon War, El Buss was apparently less affected than other parts of Tyre, especially compared to the badly hit Burj El Shemali.[69] However, at least one building close to the necropolis was hit by Israeli bombardments which also caused damage to a part of the frescoes of a Roman funerary cave.[70] This may have been the area of the Maronite Saint Paul's church on the Eastern edge of the camp since a commemorative plaque threre notes that the religious building was damaged by Israeli air strikes on 12 July and later rebuilt with funding from the Emir of Qatar.

When the Palestinian refugee camp of Nahr El Bared in northwestern Lebanon was largely destroyed in 2007 because of heavy fighting between the Lebanese Army and the militant Sunni Islamist group Fatah al-Islam, some of its residents fled to El Buss.[3]

In 2007/8, fresh water, wastewater, and stormwater systems were rehabilitated, apparently by UNRWA.[2] Until then, the sewage networks in el Buss were above the ground.[3] While the quality of life was improved by those measures, it may be argued that they were also

"affirming these structures’ permanence within a broader context of suspended time."[1]

In September 2010, three people were reportedly wounded after a dispute between clerics loyal to either Fatah or Hamas resulted in armed clashes.[71] A study by the German leftwing Rosa Luxemburg Foundation found that while Fatah is the leading faction in the camp and thus dominates the ruling Popular Committee, a host of other parties have supporters there as well, both secular and religious ones. Apart from Hamas they are the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Palestinian People's Party, the Palestinian Liberation Front (PLF), the Arab Liberation Front (ALF), the al-Nidal Front, the Islamic Jihad Movement, the Shabiha-militia, Ansar Allah and the al-Tahrir party.[72]

According to UN estimates, more than 500 refugees who fled from the Syrian civil war settled in El Buss.[2] Low-cost housing made El Buss a prime choice for them. Most were Palestinians who arrived soon after the beginning of the armed conflict in 2012,[73] adding

"another dimension of precarity to life in the camp".[1]

As of June 2018, there were 12,281 registered refugees in the El Buss camp, though this does not necessarily represent the actual number as many have left over the years,[38] Northern Europe,[50] and UNRWA does not track them.[38] In fact,

"the camp is not very lively; most of its people live abroad".[1]

Economy

According to a 2016 study by UN HABITAT, residents of El-Buss mainly work in construction and other technical jobs, particularly in the metal workshops along its Northern side,[2] though many of them are apparently owned by Lebanese.[35] In addition, many men work as day labourers in seasonal agriculture, mainly in the citrus plantations of the Greater Tyre plains area. However, levels of unemployment are high.[2]

"Emigration and a desire to escape the confines of the camp pervade life in El-Buss. It is a topic that occupies most conversations and is the ultimate goal of the youth that live in the camp."[1]

The French anthropologist Sylvain Perdigon – who lived in the El Buss camp in 2006/2007 and has been a lecturer at the American University of Beirut (AUB) since 2013 – found through his fieldwork that these precarious labor conditions make emigration the only “thinkable, desirable route” away from a dead-end future for many residents. According to his findings, the preferred destination for them is Germany.[74]

Education

UNRWA’s Al Chajra middle school in El-Bass camp provides education for up to 900 students.[75] There are three other schools as well[2] and about five kindergartens. While some children attend educational institutions outside of the camp, others who live outside the camp commute to el Buss to go to school there.[3][75]

In August 2019, the 17-year-old Ismail Ajjawi – a Palestinian graduate of the UNRWA Deir Yassin High School in El Buss[76] – made global headlines when he scored top-results to earn a scholarship to study at Harvard, but was deported upon arrival in Boston despite valid visa.[77] He was readmitted ten days later to start his studies in time.[78]

Health care

El Buss is considered unique among the twelve Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon in that there is a Lebanese public hospital within its boundaries. Located at its Eastern edge, it was reportedly constructed before 1948 and has been used mostly by Lebanese patients, especially members of the military forces.[3][35] There is also a clinic operated by UNRWA,[3] and medical laboratory for essential tests, including an X-Ray machine.[2] Some non-governmental organisations, both local and international ones, offer health services, for instance helping children with disabilities.[3]

Cultural life

El Buss is also considered to be unique among the Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon that it hosts the Maronite church of Saint Paul, which is attended both by Palestinian and Lebanese Christians.[3] This fact, along with the Lebanese public hospital, has been said to contribute to a higher degree of integration between Lebanese and Palestinians.[35] The number of houses inhabited by Palestinian Christians, which reportedly used to be around 40 percent of the population in El Buss during earlier years, was apparently down to about 15 by 2011 though. There is apparently still a tiny number of Armenians living in the camp as well.[3]

The most common mural in El Buss though is the Palestinian flag, in contrast to the flags of Amal and Hezbollah which dominate the visual-spatial landscape in Tyre. Also omnipresent in the public sphere of the camp are images of the late PLO leader Arafat and of Palestinian fighters killed in the armed resistance against the occupation as martyrs, usually combined with pictures of the Dome of the Rock in JerusalemOther common themes dealing with Palestinian identity are spray-painted images depicting narratives about the traumatic displacement events of the Nakba and life in the diaspora. Some feature Handala, the iconic symbol of Palestinian defiance created by cartoonist Naji al-Ali, who worked as a drawing instructor at Tyre's Jafariya School during the 1960s.[1]

Perdigon has researched another kind of a cultural phenomenon that he describes as "fairly ordinary" amongst many Palestinians in Lebanon, especially in El Buss and Rashidieh, which happens to be an ancient burial site as well. This phenomenon - which is known as Al Qreene - haunts people in their dreams through different forms, interrupts their lives[79] and is especially feared for causing miscarriages.[80] Perdigon lays out one exemplary case from El Buss:

"Lamis, my 45-year-old neighbor and landlady when I was living in al-Bass, had an especially long and painful engagement with al-Qreene [..]. Lamis’s mother 'had her' (i.e., al-Qreene) when she gave birth to her. Were it not for her vigilance at the time, Lamis 'would not have lived' (gheyro ma be’ish), although the price to pay was that she 'carried' al-Qreene from her mother (ijat menha iley . . . hemelet al-Qreene). Lamis started to directly confront al-Qreene herself at the onset of her first pregnancy. She lost four unborn children over the years to the frightful entity, who burst in on the scene of her dreams alternatively as 'an ugly old woman' and a mob of militiamen. Three of those losses coincided with brutal episodes of forced displacement the household suffered during the War of Lebanon (1975–90). In the very last instance in the early 1990s, al-Qreene came (ijat) in the shape of Lamis’s very own husband, who had died a few weeks before at the age of 37 from nervous exhaustion (an account confirmed by the neighborhood consensus) upon repeatedly finding himself unable to sustain his family in the context of laws and decrees excluding Palestinians from legal employment. In this uncannily familiar appearance, al-Qreene snatched away from her one of the twins (the male) she was carrying in her womb." [79]

Galleries

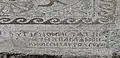

Sarcophagi

Church mosaics

The Triumphal Arch

The Hippodrome

References

- Joudi, Reem Tayseer (2018). Visions of the South : precarity and the "good life" in the visual culture of Tyre (PDF). Beirut: American University of Beirut, Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Media Studies. pp. 65–90.

- Maguire, Suzanne; Majzoub, Maya (2016). Osseiran, Tarek (ed.). "TYRE CITY PROFILE" (PDF). reliefweb. UN HABITAT Lebanon. pp. 7, 15–18, 48, 88, 96, 120. Retrieved 21 September 2020.

- Das, Rupen; Davidson, Julie (2011). Profiles of Poverty - The human face of poverty in Lebanon. Mansourieh: Dar Manhal al Hayat. pp. 347–376, 404. ISBN 978-9953-530-36-9.

- Hanafi, Sari; Chaaban, Jad; Seyfert, Karin (2012). "Social Exclusion of Palestinian Refugees in Lebanon: Reflections on the Mechanisms that Cement their Persistent Poverty". Refugee Survey Quarterly. 31 (1): 34–53. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdr018 – via Researchgate.

- Kumar, Jayant Banthia (8 October 2019). "The Population and Housing Census in Palestinian Camps and Gatherings – 2017, Detailed Analytical Report" (PDF). Beirut: Lebanese Palestinian Dialogue Committee, Central Administration of statistics, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics. pp. 231–233. Retrieved 6 May 2020.

- Doraï, Mohamed Kamel (2010). Knudsen, Are; Hanafi, Sari (eds.). Palestinian refugee camps in Lebanon. Migration, mobility and the urbanization process (PDF). Palestinian Refugees. Identity, Space and Place in the Levant. Routledge. pp. 67–80.

- A visit to the Museum... The short guide of the National Museum of Beirut, Lebanon. Beirut: Ministry of Culture/Directorate General of Antiquities. 2008. pp. 37, 39, 49, 73, 75. ISBN 978-9953-0-0038-1.

- Aubet, María Eugenia (2010). "The Phoenician cemetery of Tyre" (PDF). Near Eastern Archaeology. 73:2–3 (2–3): 144–155. doi:10.1086/NEA25754043. S2CID 165488907 – via academia.edu.

- Aubet, Maria Eugenia; Núñez, Francisco J.; Trellisó, Laura (2016). "Excavations in Tyre 1997–2015. Results and Perspectives". Berytus. LVI: 3–14 – via Academia.edu.

- Badawi, Ali Khalil (2018). TYRE (4th ed.). Beirut: Al-Athar Magazine. pp. 62–89, 102.

- Marriner, Nick; Morhange, Christophe; Meule, Samuel (June 2007). "Holocene morphogenesis of Alexander the Great's isthmus at Tyre in Lebanon". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104, 22 (22): 9218–9223. Bibcode:2007PNAS..104.9218M. doi:10.1073/pnas.0611325104. PMC 1890475. PMID 17517668 – via Academia.edu.

- Elias, Nada; Hourani, Y.; Arbogast, Rose-Marie; Sachau-Carcel, Geraldine; Badawi, Ali; Castex, Dominique (October 2016). "Human and Cattle Remains in a Simultaneous Deposit in the Hellenistic Necropolis of Jal al Bahr in Tyre: Initial Investigations". Bulletins et Mémoires de la Société d anthropologie de Paris. 29 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1007/s13219-016-0168-3. S2CID 7935393 – via Researchgate.

- Maynor Bikai, Patricia; Fulco, William J.; Marchand, Jeannie (1996). Tyre - the Shrine of Apollo. Amman: National Press. p. 81.

- Jidejian, Nina (2018). TYRE Through The Ages (3rd ed.). Beirut: Librairie Orientale. pp. 13–17, 142–169, 248–272. ISBN 9789953171050.

- de Jong, Lidewijde (October 2010). "Performing Death in Tyre: The Life and Afterlife of a Roman Cemetery in the Province of Syria". American Journal of Archaeology. 114, 4: 597–630 – via Academia.edu.

- Baratin, Laura; Bertozzi, Sara; Moretti, Elvio (2014). "3D Data in the archaeological site of Al Bass (Tyre - LEBANON)". Euro Med: 119–133 – via academia.edu.

- Khoury Harb, Antoine Emile (2017). History of the Lebanese Worldwide Presence – The Phoenician Epoch. Beirut: The Lebanese Heritage Foundation. pp. 33–34, 44–49. ISBN 9789953038520.

- Gatier, Pierre-Louis (2011). Gatier; Aliquot, Julien; Nordiguian, Lévon (eds.). Tyr l'instable : pour un catalogue des séismes et tsunamis de l'Antiquité et du Moyen Âge (PDF). in: Sources de l'histoire de Tyr. Textes de l'Antiquité et du Moyen Âge (in French). Beirut: Co-édition Presses de l'Ifpo / Presses de l'Université Saint-Joseph. p. 263. ISBN 978-2-35159-184-0.

- Mroue, Youssef (2010). Highlights of the Achievements and Accomplishments of the Tyrian Civilization And Discovering the lost Continent. Pickering. pp. 9–34.

- Medlej, Youmna Jazzar; Medlej, Joumana (2010). Tyre and its history. Beirut: Anis Commercial Printing Press s.a.l. pp. 1–30. ISBN 978-9953-0-1849-2.

- Dajani-Shakeel, Hadia (1993). Shatzmiller, Maya (ed.). Diplomatic Relations Between Muslim and Frankish Rulers 1097–1153 A.D. in. Crusaders and Muslims in Twelfth-Century Syria. Leiden, New York, Cologne: Brill. p. 206. ISBN 978-90-04-09777-3.

- Jacoby, David (2016). Boas, Adrian J. (ed.). The Venetian Presence in the Crusader Lordship of Tyre: a Tale of Decline, in. The Crusader World. New York: Routledge. pp. 181–195. ISBN 978-0415824941.

- Harris, William (2012). Lebanon: A History, 600–2011. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 48, 53, 67. ISBN 978-0195181111.

- Redding, Moses Wolcott (1875). Antiquities of the Orient unveiled, containing a concise description of the remarkable ruins of King Solomon's temple, and store cities, together with those of all the most ancient and renowned cities of the East, including Babylon, Nineveh, Damascus, and Shushan (PDF). New York: Temple Publishing Union. pp. 145, 154.

- Kahwagi-Janho, Hany (2016). "The Aqueduct of Tyre". Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies. 4, 1: 15–35. doi:10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.4.1.0015. S2CID 163792587 – via Researchgate.

- Gharbieh, Hussein M. (1996). Political awareness of the Shi'ites in Lebanon: the role of Sayyid 'Abd al-Husain Sharaf al-Din and Sayyid Musa al-Sadr (PDF) ((Doctoral)). Durham: Centre for Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies, University of Durham. p. 110.

- Smit, Ferdinand (2006). The battle for South Lebanon: Radicalisation of Lebanon's Shi'ites 1982–1985 (PDF). Amsterdam: Bulaaq, Uitgeverij. pp. 36, 71, 128, 138, 268–269, 295, 297, 300. ISBN 978-9054600589.

- Bellin, Jacques-Nicolas (1764). Le Petit Atlas maritime recueil de cartes et plans des quatre parties du Monde. 3. Paris. p. 17.

- Cassas, Louis François; Volney, Constantin-François (1800). Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoenicie, de la Palaestine et de la Basse Aegypte: ouvrage divisé en trois volumes contenant environ trois cent trente planches. 2.

- Conder, Claude Reignier; Kitchener, Horatio Herbert (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund. p. 53.

- Hamzeh, Ahmad Nizar (2004). In the Path of Hizbullah. New York: Syracuse University Press. pp. 11, 82, 130, 133. ISBN 978-0815630531.

- Migliorino, Nicola (2008). (Re)constructing Armenia in Lebanon and Syria: Ethno-Cultural Diversity and the State in the Aftermath of a Refugee Crisis. New York / Oxford: Berghahn Books. pp. 33, 83. ISBN 978-1845453527.

- Attarian, Hourig; Yogurtian, Hermig (2006). Jiwani, Yasmin; Steenbergen, Candis; Mitchell, Claudia (eds.). Survivor Stories, Surviving Narratives: Autobiography, Memory and Trauma Across Generations. Girlhood: Redifining the Limits. Montreal: Black Rose Books Ltd. p. 19. ISBN 978-1-55164-276-5.

- P. Edward Haley; Lewis W. Snider (1 January 1979). Lebanon in Crisis: Participants and Issues. Syracuse University Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-8156-2210-9.

- Roberts, Rebecca (2010). Palestinians in Lebanon: Refugees Living with Long-term Displacement. London / New York: I.B.Tauris. pp. 76, 203. ISBN 978-0-85772-054-2.

- Doraï, Mohamed Kamel (2006). "Le camp de réfugiés palestiniens d'Al Buss à Tyr : Ségrégation et précarité d'une installation durable (The Palestinian refugee camp of Al Buss in Tyr : segregation and fragility of a durable settlement)" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Association de Géographes Français (in French). 83–1: 93–104. doi:10.3406/bagf.2006.2496.

- "Rashidieh Camp". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "El Buss Camp". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA). Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- Schreiber, Gerhard; Stegemann, Bernd; Vogel, Detlef (1990). Germany and the Second World War (in German). 3. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 615. ISBN 978-0198228844.

- Schulze, Kirsten (1997). Israel's Covert Diplomacy in Lebanon. London / Oxford: Macmilllan. p. 21. ISBN 978-0333711231.

- Hirst, David (2010). Beware of Small States: Lebanon, Battleground of the Middle East. London: Faber and Faber. pp. 30–31, 42, 118, 141, 196–197. ISBN 9780571237418.

- Fisk, Robert (2001). Pity the Nation: Lebanon at War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 38, 255. ISBN 978-0-19-280130-2.

- Brynen, Rex (1990). Sanctuary And Survival: The PLO In Lebanon. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 978-0813379197.

- Goria, Wade R. (1985). Sovereignty and Leadership in Lebanon, 1943–76. London: Ithaca Press. pp. 90, 179, 222. ISBN 978-0863720314.

- Deeb, Marius (1988). "Shi'a Movements in Lebanon: their Formation, Ideology, Social Basis, and Links with Iran and Syria". Third World Quarterly. 10 (2): 685. doi:10.1080/01436598808420077.

- Siklawi, Rami (Winter 2012). "The Dynamics of the Amal Movement in Lebanon 1975–90". Arab Studies Quarterly. 34 (1): 4–26. JSTOR 41858677 – via JSTOR.

- Nisan, Mordechai (2015). Politics and War in Lebanon: Unraveling the Enigma. New Brunswick / London: Transaction Publishers. p. 55. ISBN 978-1412856676.

- Odeh, B.J. (1985). Lebanon: Dynamics of Conflict – A Modern Political History. London: Zed Books. pp. 45, 141–142, 144. ISBN 978-0862322120.

- Schiff, Ze'ev; Ya'ari, Ehud (1985). Israel's Lebanon War. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 79–80, 139. ISBN 978-0671602161.

- Doraï, Mohamed Kamel (February 2003). "Palestinian Emigration from Lebanon to Northern Europe: Refugees, Networks, and Transnational Practices". Refuge. 21 (2): 23–31. doi:10.25071/1920-7336.21287 – via Researchgate.

- Who's Who in Lebanon 2007–2008. Beirut / Munich: Publitec Publications & De Gruyter Saur. 2007. pp. 391–392, 417. ISBN 978-3-598-07734-0.

- "UNIFIL Background". United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Hussein, Muhammad (13 June 2019). "Remembering the Israeli withdrawal from south Lebanon". Middle East Monitor. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Sayigh, Yezid (Autumn 1983). "Israel's Military Performance in Lebanon, June 1982" (PDF). Journal of Palestine Studies. 13 (1): 31, 59. doi:10.2307/2536925. JSTOR 2536925 – via JSTOR.

- Abraham, Antoine J. (1996). The Lebanon War. Westport, Conn.: Praeger. p. 123. ISBN 978-0275953898.

- McDonald, Henry (6 May 2001). "20-year hunt for kidnapped Irish soldier almost over". The Observer. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Hiro, Dilip (1993). Lebanon – Fire and Embers: a History of the Lebanese Civil War. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 73. ISBN 978-0312097240.

- "The toll of three cities". The Economist. 19 June 1982. p. 26.

- Windfuhr, Volkhard (2 August 1982). "Zeigen Sie einmal Großmut!". Der Spiegel (in German). 31/1982. pp. 84–85. Retrieved 24 September 2020.

- Clive Jones; Sergio Catignani (4 December 2009). Israel and Hizbollah: An Asymmetric Conflict in Historical and Comparative Perspective. Routledge. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-135-22920-7.

- Michael E. Jansen (1 May 1983). The battle of Beirut: why Israel invaded Lebanon. South End Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-0-89608-174-1.

- Cheryl A. Rubenberg (1 January 1989). Israel and the American National Interest: A Critical Examination. University of Illinois Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-252-06074-8.

- Alagha, Joseph Elie (2006). The Shifts in Hizbullah's Ideology: Religious Ideology, Political Ideology and Political Program. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. pp. 35, 37. ISBN 978-9053569108.

- Hudson, Michael C. (1997). "Palestinians and Lebanon: The Common Story" (PDF). Journal of Refugee Studies. 10 (3): 243–260. doi:10.1093/jrs/10.3.243.

- Arsan, Andrew (2018). Lebanon: A Country in Fragments. London: C Hurst & Co. Publishers Ltd. p. 266. ISBN 978-1849047005.

- Richards, Leila (1988). The hills of Sidon: journal from South Lebanon, 1983–85. Adama Books. p. 249. ISBN 978-1557740151.

- Abousamra, Gaby; Lemaire, André (2013). "Astarte in Tyre According to New Iron Age Funerary Stelae". Die Welt des Orients. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht (GmbH & Co. KG). 43, H. 2 (2) (2): 153–157. doi:10.13109/wdor.2013.43.2.153. JSTOR 23608852.

- Barak, Oren (2009). The Lebanese Army: A National Institution in a Divided Society. Albany: State University of New York Press. pp. 67, 180. ISBN 978-0-7914-9345-8.

- "Why They Died: Civilian Casualties in Lebanon during the 2006 War". Human Rights Watch. 5 September 2007. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- Toubekis, Georgios (2010). Machat, Christoph; Petzet, Michael; Ziesemer, John (eds.). Lebanon: Tyre (Sour) (PDF). Heritage at Risk: ICOMOS World Report 2008-2010 on Monuments and Sites in Danger. Berlin: Hendrik Bäßler verlag. pp. 118–120. ISBN 978-3-930388-65-3.

- Hanafi, Sari. "ENCLAVES AND FORTRESSED ARCHIPELAGO VIOLENCE AND GOVERNANCE IN LEBANON'S PALESTINIAN REFUGEE CAMPS". Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- "Flucht und Vertreibung im Syrien-Konflikt - Eine Analyse zur Situation von Flüchtlingen in Syrien und im Libanon" (PDF). Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung (in German). July 2014. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- Knudsen, Are John (March 2018). "The Great Escape? Converging Refugee Crises in Tyre, Lebanon". Refugee Survey Quarterly. 37, 1: 96–115. doi:10.1093/rsq/hdx018.

- Perdigon, Sylvain (2011). Between the Womb and the Hour: Ethics and Semiotics of Relatedness amongst Palestinian Refugees in Tyre, Lebanon (Doctoral Dissertation). Ann Arbor. p. 50.

- Harake, Dani; Kuwalti, Riham (31 May 2017). "Maachouk Neighbourhood Profile & Strategy, Tyre, Lebanon" (PDF). reliefweb. UN HABITAT Lebanon. p. 7. Retrieved 22 September 2020.

- "Harvard-bound Ismail Ajjawi an inspiration to fellow UNRWA students". United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA). 30 August 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- Avi-Yonah, Shera S.; Franklin, Delano R. (27 August 2019). "Incoming Harvard Freshman Deported After Visa Revoked". The Harvard Crimson. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- "Freshman Previously Denies Entry to the United States Arrives at Harvard". The Harvard Crimson. 3 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- PERDIGON, Sylvain (2018). "Life on the cusp of form: In search of worldliness with Palestinian refugees in Tyre, Lebanon". HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory. 8 (3): 566–583. doi:10.1086/701101. S2CID 149533991.

- Perdigon, Sylvain (2015). Das, Veena; Han, Clara (eds.). Bleeding dreams: Miscarriage and the bindings of the unborn in the Palestinian refugee community of Tyre, Lebanon. Living and dying in the contemporary world: A compendium. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 143–158. ISBN 9780520278417.

_-_Arab_People_fleeing.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)