Elaeocarpus dentatus

Elaeocarpus dentatus, commonly known as hinau (Maori: hīnau), is a native lowland forest tree of New Zealand. Other names in Māori for the tree are hangehange, pōkākā and whīnau.

| Elaeocarpus dentatus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Rosids |

| Order: | Oxalidales |

| Family: | Elaeocarpaceae |

| Genus: | Elaeocarpus |

| Species: | E. dentatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Elaeocarpus dentatus (J.R.Forst.& G.Forst.) Vahl. | |

| |

| Natural range of Hīnau | |

A member of the family Elaeocarpaceae, it is found on both the North and South Islands of New Zealand, but not on Stewart Island.[1] The leaves are dark green, with a toothed edge. On the underside of the leaf small domatia are present.[2] Clusters of small white flowers are produced in spring, and in late summer the flowers form into a fleshy fruit.[3]

It was officially first recorded for science by botanists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander on 5 November 1769.[4]

Description

Elaeocarpus dentatus is a tree which grows to around 18 m (59 ft.) tall and has a trunk of around 1 m (3.2 ft.) in diameter with greyish bark which roughens with age.[5] It has leathery leaves[6] which are 10–12 cm long and 2–3 cm wide. On top they are a dark green and an off-white colour below.

It flowers from October to February with flowers very similar to the lily of the valley extending off of 10–18 cm long racemes, each one bearing 8 - 10 flowers. [7] The flowers (around 12mm in diameter) are white and droop down, connected to the Raceme by 1 cm long silky pedicels.[8] They are made of 3 - 5 petals which are lobed at their tips and have long anthers which extend out on short filaments. The sepals are covered with many tiny hairs. [7]

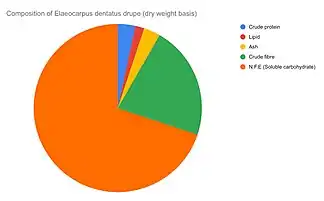

It fruits from December through to when it ripens in May.[5][8] The fruit are purple-black egg-shaped drupes which are 12–18 mm long and 9 mm wide[5][8] and are attractive to birds.[6] It has 2-celled ovaries and a rugulose (wrinkly) endocarp.[9] The drupes are very fleshy, the flesh making up 56% of the mass, and have a relatively low level of water at 66%.[10] They have a mean mass of 1.05g and have the following compositional breakdown (after moisture is removed): 69.9% N.F.E (Soluble carbohydrates), 21.8% Crude Fiber, 3.4% Crude protein, 3.2% Ash, and 1.7% Lipid.[11]

Hīnau flowers

Hīnau flowers Hīnau foliage

Hīnau foliage Hīnau drupes (fruit)

Hīnau drupes (fruit) Chemical composition of drupe after moisture is removed

Chemical composition of drupe after moisture is removed

The hīnau is bisexual, meaning its flowers contain both the male (stamen) and female (carpel) parts, and has 15 pairs of chromosomes (2n = 30).[12][13] It is very similar to Elaeocarpus hookerianus but can be distinguished by its larger leaves, flowers and fruit, and its lack of E. hookerianus's distinctive divaricating juvenile to sub-adult form.[8]

The heartwood is dark brown and the sapwood is white, the heartwood, being heavy and strong, is used for making fence posts. It is, however, rarely milled because it is often hollow inside.[14]

Ecology

Elaeocarpus dentatus is relatively common, classified as "Not Threatened," and is used by many organisims for a variety of purposes.[15]

North Island brown kiwi

A 1982 study suggested that North Island brown kiwi use the seeds as grinding agents to help break down food after analysing the gizzards of 50 birds. They found that around 50% of Gizzards containded Hīnau seeds and that the more seeds a kiwi had, the smaller the amount of grit present. This was also reflected in their finding that the seeds were all "abraded smooth," meaning they had been used for long periods of time.[16]

Flightless invertebrates

In New Zealand forests the trunks of trees are crucial to flightless invertebrates who use them as a way to reach the canopy for food and breeding. A 1983 study used traps to study the kinds of these organisms that were coming up and down tree trunks of Hīnau over a 19 month period. The most prevelant speices coming up the tree trunks were Springtails makings up 39% of all the species. Wasps and ants made up 10%, Spiders 9%, Beetles and Weevils 8% and Mites 7%. The least prevelant species were termites and ant-lions who were not recorded at all. Coming down the trunk there were only 17% the number of (flightless) inverterbrates that were found coming up. The most common were the mites, making up 15%. Followed by larvae with 11%, springtails with 11%, and harvestmen with 9%.[17]

Kākā on Kāpiti Island

On Kāpiti Island Hīnau fruit is a very important food source for Kākā, as demonstrated by a 1997 study which radio tagged birds on the island to find out their sources of food. In March all the tagged birds ate mostly or almost entirely Hīnau fruit for the month, with males continuing until June and females stopping after March. It is unclear why but is hypothisised that the hardening of the drupes in the following months means that females, who have a different shaped mandible, cannot break into them as easily as males can. When Kākā are feeding their young on Kāpiti Island, they rely heavily on Hīnau and Tawa to do so. Both because of their prevelance on the island and their abundant crop of fruit. [19] They mainly eat the fruit by splitting them open and eating the still developing seed as the fruit only ripens in May, digesting an average of 7.1 seeds per minute in March.[19] [20][8]

Weka

Weka are important dispersers of Hīnau seeds but on the mainland, weka are quite rare and so most fruit on the ground is eaten by pigs and rodents, on predator free islands though, they disperse 76.5% of seeds - much more than their flying counterparts with only 13.7% of canopy seeds dispersed. Given that these areas are representative of New Zealand pre-pests it suggests that the majority of dispersal was by flightless birds and that now, after the extinction of most of them, weka have been given the task of doing the lion-share of dispersal. This makes them extremely important to the long term success of the Hīnau and the re-introduction to their historic ranges should be a priority. Though more research is needed, it appears that (Hīnau) seeds germinate better after the coat has been torn open and that the grit in weka gizzards abrades the fruit to a similar effect. It is yet to be seen how far and where weka disperse the seeds to, however, meaing the quality of their dispersal is not yet known.[21]

Other species

Kōkako eat both the leaves and fruit, though they make up a very small proportion of the bird's varied and complex diet.[22] The extremely hard endocarp is thought to be for protection inside the digestive systems of large flightless birds who acted as another disperser by eating fallen fruit. It is also possible, however, that it is to balance the over-eating of their fruit by parrots, like, for example the Kākā, which is described above.[23] Kererū also eat the fruit and act as a disperser, though not as much as weka do.[21]

Etymology

From the Latin "elaeocarpus" meaning olive-seed and "dentatus" meaning toothed.[8]

Distribution

Elaeocarpus dentatus is endemic to New Zealand and found in both the North and South Islands down to South Westland and Christchurch on the east and west.[8] It grows from sea level to 600 m (1970 ft.), essentially anywhere north of the latitude 43˚30'S.[5][7]

Varieties

There is a variety called Elaeocarpus dentatus var. obovatus (Cheeseman) which is recognised by New Zealand Flora but not by Druce (1993).[8] It is listed as a synonym of Elaeocarpus dentatus by both The Plant List[24] and World Flora Online,[25] which superseded it.[26] It was mentioned in a Department of Conservation (New Zealand) Conservation Status Report published in 2017, under the heading: "Data Deficient."[27]

This variety is, however, clearly very distinctive and has much wider leaves (5–7 long and 3–5 cm wide).[28]

Cultivation

Elaeocarpus dentatus prefers a rich, moist soil in partial shade.[6] To grow, press the seed well in and cover with 5mm of soil. It takes around 6 months to germinate and fresh fruit can be used.[29][8]

In Māori culture

Mythology

In Māori mythology Māui discovers the origin of fire by stealing the nails of his grandmother Mahuika, the atua (God) of fire, extinguising each one. After realising that Māui had taken all of her fire she threw her last nail at him. It missed and landed first in the Rata (all species under NZ), Hīnau, Kahikatea, Rimu, Mataī, and Miro trees who rejected the fire. It then went on, landing in the kaikōmako, tōtara, patete, pukatea, and māhoe trees who received the fire, considering it a great gift. The trees that accepted the fire can be used to create fire by rubbing dry sticks together, those that do not, like the Hīnau, will not produce fire in this way.[30][31]

Food

The mealy substance which covers the kernal of the Hīnau's Drupe (similar to that of an Olive) was used by Māori to make a kind of cake or bread.[32][33] Though the Drupes are edible raw, to make the cake they would first pound the fruits (the club made of maire or stone) in order to separate the nuts, stalks and bits of broken skin in a trough called a "kumete", leaving the course grey meal behind, a process called "Tuki." The meal is then sifted through baskets make of Cabbage tree leaves such that the stones are trapped in the basket, known as a "tatari" or "Kete puputu." They are then seived through a finer seive to make sure that none of the stones known as "karihi," "iwi," or "iho" escape. Afterwards, the meal was moulded into a large cake which is then cooked for several hours in a Hāngi, wrapped inside a Rangiora leaf.[33][34][35]

Although some Europeans claimed it had a "harsh taste",[36] Māori considered it a great luxury[34] as demonstrated in their saying: "Kia whakaara koe i taku moe, ko te whatu turei a Rua" meaning "When you awaken me from my sleep let it be for the purpose of eating the whatu turei a Rua (Hīnau meal). [33]

Despite European opinion, Elaeocarpus dentatus's seeds are in fact a good thing to eat as they contain some fatty acids which are protective against Cardiovascular disease.[37]

Because some meal was still left on the stones, water was used to rub the meal off the stones, the combination drunk as a sort of Gruel, as it would be called in a western context, and known to Māori as "wai haro."[33] It was also sometimes fed to sick people.[38]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Elaeocarpus dentatus. |

- "Hīnau, Elaeocarpus - Faculty of Science - The University of Science". The University of Auckland. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- "Elaeocarpaceae 2 (Wineberry family) - Faculty of Science, University of Auckland". Archived from the original on 16 July 2012. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus Hinau". bushmansfriend.co.nz. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- http://collections.tepapa.govt.nz/objectdetails.aspx?oid=328198

- Salmon JT (1998). Native Trees of New Zealand: v. 1 (Mobil New Zealand Nature Series). New Zealand: Reed Publishing. pp. 39 (There are no page numbers this is the number that Hīnau is given). ISBN 0790005581.

- Paddison V (1999). The Gardener's Encyclopaedia of New Zealand Native Plants. New Zealand: Random House. p. 205. ISBN 1869620925.

- Eagle A (2006). Eagles Complete Trees and Shrubs of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: Te Papa Press. p. 270. ISBN 9780909010089.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus var. dentatus". New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Flora of New Zealand | Taxon Profile | Elaeocarpus dentatus". www.nzflora.info. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- Williams CK (1982). "Nutritional Properties of Some Fruits Eatenby the Possum Trichosurusvulpecula in Anew Zealand Broadleaf – Podocarp Forest" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 5: 17.

- Williams CK. "Nutritional Properties of Some Fruits Eatenby the Possum Trichosurusvulpecula in Anew Zealand Broadleaf – Podocarp Forest" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 5: 17 & 18 – via https://newzealandecology.org.

- Beentje H (2010). The Kew Plant glossary : an illustrated dictionary of plant terms. Williamson, Juliet. Richmond, Surrey: Kew. ISBN 978-1-84246-422-9. OCLC 464589004.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus - The University of Auckland". www.nzplants.auckland.ac.nz. Retrieved 18 December 2020.

- Cockayne L, Turner EP (1928). The trees of New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: W.A.G. Skinner. p. 150.

- "NZTCS". nztcs.org.nz. Retrieved 31 January 2021.

- Reid B, Ordish RG, Harrison M (January 1982). "An analysis of the gizzard contents of 50 North Island brown kiwis, Apteryx australis mantelli, and notes on feeding observations" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 5: 76–85. JSTOR 24052678.

- Moeed A, Meads MJ (January 1983). "Invertebrate fauna of four tree species in Orongorongo Valley, New Zealand, as revealed by trunk traps" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology: 39–53.

- "[Vespula] wasps in New Zealand". Manaaki Whenua. Retrieved 4 February 2021.

- Ron J. Moorhouse. "THE DIET OF THE NORTH ISLAND KAKA (NESTOR MERIDIONALIS SEPTENTRIONALIS) ON KAPITI ISLAND" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 21: 143–150.

- Joanna K. Carpenter Dave Kelly Elena Moltchanova Colin F. J. O'Donnell (2018). "Introduction of mammalian seed predators and the loss of an endemic flightless bird impair seed dispersal of the New Zealand tree Elaeocarpus dentatus". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (12): 5994. doi:10.1002/ece3.4157. PMC 6024123. PMID 29988419. S2CID 49654569 – via Wiley Online Library.

- Carpenter JK, Kelly D, Moltchanova E, O'Donnell CF (June 2018). "Introduction of mammalian seed predators and the loss of an endemic flightless bird impair seed dispersal of the New Zealand tree Elaeocarpus dentatus". Ecology and Evolution. 8 (12): 5992–6004. doi:10.1002/ece3.4157. PMC 6024123. PMID 29988419.

- R.O. POWLESLAND. "THE FOODS, FORAGING BEHAVIOUR AND HABITAT USE OF NORTH ISLAND KOKAKO IN PUKETI STATE FOREST, NORTHLAND" (PDF). New Zealand Journal of Ecology. 10: 120–127.

- Michael James Thorsen, Katharine J.M. Dickinson and Philip J. Seddon. "Seed dispersal systems in the New Zealand flora". Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 11: 302 – via Researchgate.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus var. obovatus Cheeseman – The Plant List". www.theplantlist.org. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus var. obovatus Cheeseman". www.worldfloraonline.org. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Home – The Plant List". www.theplantlist.org. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- de Lange PJ, Rolfe JR, Barkla JW, Courtney SP, Champion PD, Perrie LR, Beadel SM, Ford KA, Breitwieser I, Schönberger I, Hindmarsh-Walls R, Heenan PB, Ladley K (30 November 2020). "Conservation status of New Zealand indigenous vascular plants, 2017" (PDF). New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. p. 22.

- "Elaeocarpus dentatus var. obovatus". New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Retrieved 29 November 2020.

- "Seed collection and propagation guide for native trees and shrubs". www.doc.govt.nz. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- "How Māui brought fire to the world / Māori Myths, Legends and Contemporary Stories / Te Reo Māori / Support materials / Home - Mātauranga Māori". eng.mataurangamaori.tki.org.nz. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- Taylor, Richard (1855). Te Ika a Maui, or New Zealand and its inhabitants. USA: Wertheim and Macintosh. p. 30.

- Salmon, John T. (1986). The Native Trees of New Zealand. New Zealand: Heinemann Reed. p. 176. ISBN 0790001047.

- Elsdon, Best (1903). "Food products of Tuhoeland: being notes on the food-supplies of a non-agricultural tribe of the natives of New Zealand: together with some account of various customs, superstitions etc. pertaining to foods". Transactions of the New Zealand Institute.: 55–56.

- Papakura, Maggie (1938). The Old-time Maori. London, UK: Gollancz. p. 211.

- Taylor, Richard (1855). Te Ika a Maui, or New Zealand and its inhabitants. USA: Wertheim and Macintosh. p. 393.

- (Rev.) Richard, Taylor (1848). A leaf from the natural history of New Zealand; or, a vocabulary of its different productions &c.,&c., with their native names. New Zealand: Robert Stokes; J. Williamson.

- Cambie RC, Ferguson LR (2003). "Potential functional foods in the traditional Maori diet". Mutation Research. 523–524: 109–17. doi:10.1016/s0027-5107(02)00344-5. PMID 12628508.

- Best, Eldson (1942). "Forest lore of the Māori". Dominion Museum Bulletin.

- Taylor, Richard (1855). Te Ika a Maui, or New Zealand and its inhabitants. USA: Wertheim and Macintosh. p. 446.

- Best, Elsdon. "Maori forest lore : being some account of native forest lore and woodcraft, as also of many myths, rites, customs, and superstitions connected with the flora and fauna of the Tuhoe or Ure-wera District - Part 1". Transactions of the New Zealand Institute.

- Taylor, Richard (1855). Te Ika a Maui, or New Zealand and its inhabitants. USA: Wertheim and Macintosh. p. 391.

- Best, Elsdon. "Forest lore of the Māori". Dominion Museum Bulletin. 14.