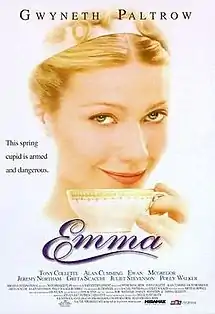

Emma (1996 theatrical film)

Emma is a 1996 period comedy film based on the 1815 novel of the same name by Jane Austen. Written and directed by Douglas McGrath, the film stars Gwyneth Paltrow, Alan Cumming, Toni Collette, Ewan McGregor, and Jeremy Northam.

| Emma | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Douglas McGrath |

| Produced by | Patrick Cassavetti Steven Haft |

| Screenplay by | Douglas McGrath |

| Based on | Emma by Jane Austen |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Rachel Portman |

| Cinematography | Ian Wilson |

| Edited by | Lesley Walker |

Production company | Matchmaker Films Haft Entertainment |

| Distributed by | Miramax Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 120 minutes[1] |

| Country | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $7 million[2] |

| Box office | $22.2 million[3] |

Plot

In early 19th-century England, Emma Woodhouse, is a congenial but naïve young woman. After her governess, Miss Taylor, marries Mr Weston, Emma proudly takes credit for bringing the couple together and now considers herself a matchmaker within her small community. Her father and old family friend, George Knightley, whose brother is married to Emma's sister, dispute her claim and discourage any further matchmaking attempts. Ignoring their warnings, she schemes to match Mr Elton, the village minister, with her friend, Harriet Smith, a rather unsophisticated young woman on the verges of society.

Robert Martin, a respectable local farmer, proposes to Harriet, who is inclined to accept, though Emma, believing Harriet can have better prospects, urges her to refuse him. Meanwhile, Mr Elton has shown a desire for Emma by excessively admiring a portrait she drew of Harriet and otherwise engaging with her to secure Emma's favor. Emma misinterprets his actions as an attraction to Harriet. However, when Mr Elton and Emma are alone, he fervently declares his love for Emma, who strongly rejects his attention. Soon after, he marries another woman, a vain socialite who competes with Emma for status in the community.

Over the next few months, various gatherings show who loves whom among Emma's friends. Emma is briefly attracted to the charming and gallant Frank Churchill, Mr Weston's son, who is visiting from London, though Emma soon decides to match him with Harriet. However, Frank is secretly engaged to Jane Fairfax. His aunt, who later dies, would have disapproved the match and disinherited Frank. He feigned interest in Emma as a deflection. Harriet states she has no interest in Frank, preferring Mr Knightley, who kindly danced with her at a ball after Mr Elton snubbed her. Mr Knightley has started to fall in love with Emma.

During a picnic in the countryside, Emma ridicules Miss Bates, deeply hurting her. After, Mr Knightley angrily scolds Emma for humiliating someone living in lesser social circumstances. Emma later works to make amends with Miss Bates. Mr Knightly leaves town to visit his brother, and Emma finds herself frequently thinking about him during his absence. She does not realize she loves him until Harriet expresses her feelings for him. When Mr Knightley returns, he and Emma meet and have a conversation that begins awkwardly but ends with him proposing and her gladly accepting. Their engagement upsets Harriet, who avoids Emma, but returns a few weeks later, happily engaged to Mr Martin, whom she always loved. The film ends with Emma and Mr Knightley's wedding.

Cast

- Gwyneth Paltrow – Emma Woodhouse

- Toni Collette – Harriet Smith

- Alan Cumming – Philip Elton

- Ewan McGregor – Frank Churchill

- Jeremy Northam – George Knightley

- Greta Scacchi – Anne Taylor Weston

- Juliet Stevenson – Augusta Hawkins Elton

- Polly Walker – Jane Fairfax

- Sophie Thompson – Miss Bates

- James Cosmo – Mr. Weston

- Denys Hawthorne – Henry Woodhouse

- Phyllida Law – Mrs. Bates

- Kathleen Byron – Mrs. Goddard

- Karen Westwood – Isabella Woodhouse

- Edward Woodall – Robert Martin

- Brian Capron – John Knightley

- Angela Down – Mrs. Cole

- John Franklyn-Robbins – Mr. Cole

- Ruth Jones – Bates' Maid

Production

Conception and adaptation

Douglas McGrath "fell in love" with Jane Austen's 1815 novel Emma, while he was an undergraduate at Princeton University. He believed the book would make a great film, but it was not until a decade later that he was given a chance to work on the idea.[4] After receiving an Academy Award nomination in 1995 for his work on Bullets over Broadway, McGrath decided to make the most of the moment and took his script idea for a film adaptation of Emma to Miramax Films.[4] McGrath had initially wanted to write a modern version of the novel, set on the Upper East Side of New York City. Miramax's co-chairman, Harvey Weinstein, liked the idea of a contemporary take on the novel.[4] McGrath was unaware that Amy Heckerling's Clueless was already in production until plans for Emma were well underway.[4]

Casting

McGrath decided to bring in American actress Gwyneth Paltrow to audition for Emma Woodhouse, after a suggestion from his agent and after seeing her performance in Flesh and Bone.[5] Of his decision to bring Paltrow in for the part, McGrath revealed "The thing that actually sold me on her playing a young English girl was that she did a perfect Texas accent. I know that wouldn't recommend her to most people. I grew up in Texas, and I have never heard an actor or actress not from Texas sound remotely like a real Texan. I knew she had theater training, so she could carry herself. We had many actresses, big and small, who wanted to play this part. The minute she started the read-through, the very first line, I thought, 'Everything is going to be fine; she's going to be brilliant.'"[5] Following the read-through, the co-chairman of Miramax, Harvey Weinstein, decided to give Emma the green-light. However, he wanted Paltrow to appear in The Pallbearer first, before going ahead and allowing the film to be made.[5] While she recovered from wisdom-tooth surgery, Paltrow had a month to herself to do her own research for the part.[6] She also studied horsemanship, dancing, singing, archery and the "highly stylized" manners and dialect during a three-week rehearsal period.[6]

Jeremy Northam revealed that when he first tried to read Emma, he did not get very far and was not a fan.[7] When he read the script for the film, he was initially considered for another role, but he wanted to play George Knightley.[7] He stated "When I met the director, we got on very well and we talked about everything except the film. At the end of it, he said he thought Knightley was the part for me, so I didn't have to bring up the issue at all."[7] Northam added that Knightley's faith in Emma becoming a better person was one of the reasons he loved the character.[7] Australian actress Toni Collette was cast as Harriet Smith.[8] Collette also struggled to get into the Austen books when she was younger, but after reading Emma, which she deemed "warm and witty and clever", she began to appreciate them more.[8] Collette had to gain weight to portray "the Rubenesque Harriet" and she explained "I think it's important for people to look real in films. There's a tendency to go Barbie doll and I don't agree with that at all."[8]

Ewan McGregor was cast as Frank Churchill. He told Adam Higginbotham from The Guardian that he chose to star in Emma because he thought it would be something different from his previous role in Trainspotting.[9] McGregor later regretted appearing in the film, saying "My decision-making was wrong. It's the only time I've done that. And I learnt from it, you know. So I'm glad of that – because it was early on and I learnt my lesson. It's a good film, Emma, but I'm just... not very good in it. I'm not helped because I'm also wearing the world's worst wig. It's quite a laugh, checking that wig out."[9] Real-life mother and daughter, Phyllida Law and Sophie Thompson, portrayed Mrs and Miss Bates.[10] Thompson revealed that it was a coincidence that she and her mother were cast alongside each other, as the casting director had their names on separate lists.[10] McGrath initially believed Thompson to be too young to play Miss Bates, but he changed his mind after seeing her wearing glasses with her hair down.[10]

Alan Cumming appeared as Reverend Philip Elton, who falls in love with Emma.[11] Cumming wrote on his official website that the friendship that developed between himself and McGrath was one of the most memorable things about his time working on the film.[12] He went on to state that the worst thing about the shoot was his hair, which had been lightened and curled for the character.[12] Juliet Stevenson portrayed the "ghastly" Mrs Elton, while Polly Walker and Greta Scacchi starred as Jane Fairfax and Anne Taylor respectively.[13][14][15] Other cast members included Edward Woodall as Robert Martin, James Cosmo as Mr Weston and Denys Hawthorne as Mr Woodhouse, in one of his last film appearances.[16][17]

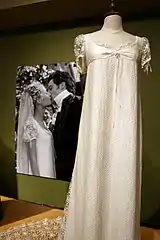

Costume design

British costume designer Ruth Myers created and designed the clothing for the film.[18] She wanted to mirror the lightness of the script within the costumes and give "a spark of color and life" to the early 19th century setting.[19] During her research, Myers noted a similarity between the fashions after the Napoleonic Wars and the 1920s, saying that they had "the same sort of flapperish quality".[19] The designer explained "The moment I set to research it, more and more it kept striking me what the similarities were between the two periods. It was a period of freedom of costume for women, and it was a period of constant diversions for the upper classes–picnics, dinners, balls, dances. What I wanted to do was make it look like the watercolors of the period, which are very bright and very clear, with very specific colors."[19]

Myers went on to reveal that she did not want the costumes to have a "heavy English look" and instead she wanted "to get the freedom of bodies that you see in all the drawings, the form of the body underneath, the swell of the breasts."[19] Myers told Barbara De Witt from the Los Angeles Daily News that using pastel-colored clothing to get the watercolor effect was one of her major challenges during the production.[18] The designer was later criticised for being inaccurate, but she stated that she did not want the costumes to look old or sepia.[19] Myers only had five weeks in which to create 150 costumes for the production, and she was constantly working on the set.[18]

Emma's wedding dress was made from silk crepe and embroidered with a small sprig pattern, while the sleeves and the train were made from embroidered net.[20] Of the dress, Myers stated "The inspiration for Emma's wedding dress began with a small amount of exquisite vintage lace that became the overlay. I wanted a look that would work not only for the period but also one that would compliment Gwyneth Paltrow's youth, swan neck, and incredible beauty. I was also hoping to evoke happiness and the English countryside; the sun did shine on the day we shot the scene!"[20]

Music

| Emma [Original Score] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | 29 July 1996 | |||

| Genre | Film score | |||

| Length | 42:45 | |||

| Label | Hollywood Records | |||

| Rachel Portman chronology | ||||

| ||||

The musical score of the film was written by British composer Rachel Portman. It was released on 29 July 1996 by Hollywood Records.[21] Portman told Rebecca Jones from the BBC that her score was "purely classical". She continued "It is an orchestral piece, by which I mean that there is nothing in it that you wouldn't find in a symphony orchestra. It was influenced by my roots and my classical background."[22] Portman used various instruments to give a voice to the characters. She revealed that "a quivering violin" would represent Harriet's uneasy stomach, while "a bittersweet clarinet" would accompany Emma though her emotional journey.[23] Josh Friedman from the Los Angeles Times believed Portman's "crafty score guides the audience through the heroine's game playing, and ultimately, to her romantic destiny."[23] He also thought the music had "a sneaky, circular feel".[23]

Playbill's Ken LaFave commented that the score "underlined the period romanticism" in Emma and contained a "string-rich, romantic sound".[24] Jason Ankeny, a music critic for Allmusic, wrote that Portman's score to Emma employed all of her "signatures" like "whimsical yet romantic melodies, fluffy string arrangements, and woodwind solos", which would be familiar to anyone who had listened to her previous film scores.[21] He stated, "it seems as if she's simply going through the motions, content to operate within the confines of an aesthetic that, admittedly, is hers and hers alone. By no means a bad score, Emma is nevertheless a disappointment – if you've heard a previous Rachel Portman score, you've pretty much heard this one as well."[21] On 24 March 1997, Portman became the first woman to win the Academy Award for Best Original Score.[25] The album contains 18 tracks; the first track is "Main Titles", and the final track is "End Titles".[21]

Comparisons with the novel

Although in general staying close to the plot of the book, the screenplay by Douglas McGrath enlivens the banter between the staid Mr Knightley and the vivacious Emma, making the basis of their attraction more apparent.

Austen's original novel deals with Emma's false sense of class superiority, for which she is eventually chastised. In an essay from Jane Austen in Hollywood, Nora Nachumi writes that, due partly to Paltrow's star status, Emma appears less humbled by the end of this film than she does in the novel.[26]

Reception

Critical response

The film has received generally positive reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes gives the film an approval rating of 84% based on reviews from 50 critics, with a rating average of 7.1 out of 10. The consensus writes: "Emma marks an auspicious debut for writer-director Douglas McGrath, making the most of its Jane Austen source material – and a charming performance from Gwyneth Paltrow."[27] Metacritic gives the film a rating of 66 out of 100 based on reviews from 22 critics.[28]

Ken Eisner, writing for Variety, proclaimed "Gwyneth Paltrow shines brightly as Jane Austen's most endearing character, the disastrously self-assured matchmaker Emma Woodhouse. A fine cast, speedy pacing and playful direction make this a solid contender for the Austen sweepstakes."[2]

Accolades

| Award | Category | Recipients | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards[29] | Best Costume Design | Ruth Myers | Nominated |

| Best Original Musical or Comedy Score | Rachel Portman | Won | |

| London Film Critics' Circle | British Actor of the Year | Ewan McGregor | Won |

| Satellite Awards[30] | Best Performance by an Actress in a Comedy or Musical | Gwyneth Paltrow | Won |

| USC Scripter Award[31] | USC Scripter Award | Douglas McGrath, Jane Austen | Nominated |

| Writers Guild of America[32] | Best Adapted Screenplay | Douglas McGrath | Nominated |

See also

- "Silent Worship" (song sung by Emma and Mr Churchill)

- Emma - 2020 film

References

- "Emma (U)". British Board of Film Classification. 10 June 1996. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- Eisner, Ken (9 June 1996). "Emma". Variety. Penske Business Media. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Emma at Box Office Mojo

- Chollet, Laurence (11 August 1996). "Clued into Austen's 'Emma'". The Record. North Jersey Media Group. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Clark, John (21 July 1996). "The Girl Can't Help It". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Strauss, Bob (31 July 1996). "Plain Jane : Not a 'Clueless' remake of Austen, 'Emma' tackles classic story head-on". Los Angeles Daily News. MediaNews Group. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Donnelly, Rachel (14 September 1996). "An ideal squeeze Jeremy Northam is the latest hero of a screen Jane Austen". The Irish Times. Irish Times Trust. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Ganahl, Jane (4 August 1996). "Aussie actress shines in the latest Austen outing". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Corporation. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

- Higginbotham, Adam (7 September 2003). "Scot free". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 27 November 2012.

- Gritten, David (28 July 1996). "Mother-daughter Comedy Team". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- Mills, Nancy (29 November 1995). "Jumping From the Bard to 'GoldenEye'". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Emma". Alancumming.com. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2012.

- Malcolm, Derek (31 December 1996). "Jane Austen on saccharine". Mail & Guardian. M&G Media Ltd. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- "Polly Walker". BBC. April 2007. Archived from the original on 5 February 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Kunz, Mary (28 April 2000). "Endurance test". The Buffalo News. Berkshire Hathaway. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- Corliss, Richard (29 July 1996). "Cinema: A touch of class". Time. Time Inc. Retrieved 30 November 2012.(subscription required)

- Norman, Neil (1 November 2009). "Denys Hawthorne obituary". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 30 November 2012.

- De Witt, Barbara (13 March 1997). "Costume Couture: Designers create characters with clothing fit for an Oscar". Los Angeles Daily News. MediaNews Group. Archived from the original on 30 July 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Calhoun, John (1 October 1997). "Myers' way: Costume designer Ruth Myers runs the stylistic gamut with 'LA Confidential' & 'A Thousand Acres'". AccessMyLibrary. Gale. Archived from the original on 5 February 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2012.

- "Emma". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Jason, Ankeny. "Emma (Original Score)". Allmusic. All Media Guide. Archived from the original on 14 February 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Jones, Rebecca (13 August 2001). "Proms go to the movies". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Friedman, Josh (5 August 2002). "Music's Key Role in Movies' Moods". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. Archived from the original on 18 December 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- LaFave, Ken (1 February 2003). "Composer's Notes". Playbill. Archived from the original on 6 February 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Whitney, Hilary (13 December 1999). "Networking women". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Archived from the original on 7 May 2014. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- Peter M. Nichols, The New York Times Essential Library: Children's Movies, Times Books, 2003, ISBN 0-8050-7198-9,

- "Emma (1996)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Archived from the original on 6 November 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Emma". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Archived from the original on 1 May 2018. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "The 69th Academy Awards (1997) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Golden (not Globe) Awards Recognize Finest In Hollywood". Los Angeles Daily News. MediaNews Group. 17 January 1997. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 23 November 2012.(subscription required)

- Johnson, Ted (2 January 1997). "USC script noms set". Variety. PMC. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

- "Writers Guild Of America Offers Awards Nominees". Sun-Sentinel. Tribune Company. 8 February 1997. Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 23 November 2012.

External links

- Emma at IMDb

- Emma at AllMovie

- Emma at Box Office Mojo

- Emma at Rotten Tomatoes

- Emma at Metacritic