Enigma (2001 film)

Enigma is a 2001 espionage thriller film directed by Michael Apted from a screenplay by Tom Stoppard. The script was adapted from the 1995 novel Enigma by Robert Harris, about the Enigma codebreakers of Bletchley Park in the Second World War.

| Enigma | |

|---|---|

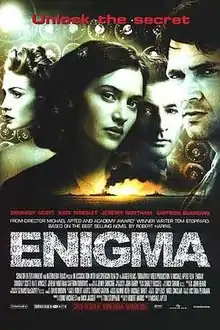

Theatrical release poster. | |

| Directed by | Michael Apted |

| Produced by | |

| Screenplay by | Tom Stoppard |

| Based on | Enigma by Robert Harris |

| Starring | |

| Music by | John Barry |

| Cinematography | Seamus McGarvey |

| Edited by | Rick Shaine |

Production company |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date | |

Running time | 119 min. |

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Box office | $15,705,007 (Worldwide)[1] |

Although the story is highly fictionalised, the process of encrypting German messages during World War II and decrypting them with the Enigma is discussed in detail, and the historical event of the Katyn massacre is highlighted. It was the last film scored by John Barry.

Plot

The story, loosely based on actual events, takes place in March 1943, when the Second World War was at its height. The cryptanalysts at Bletchley Park, Buckinghamshire, have a problem: the Nazi U-boats have changed one of their code reference books used for Enigma machine ciphers, leading to a blackout in the flow of vital naval signals intelligence. The British cryptanalysts have cracked the "Shark" cipher once before, and they need to do it again in order to keep track of U-boat locations.

The film begins with Tom Jericho returning to Bletchley after a month recovering from a nervous breakdown brought on by his failed love affair with a coworker named Claire Romilly. Jericho immediately seeks to see her again and finds that she mysteriously disappeared a few days earlier. He enlists the help of Claire's housemate, Hester Wallace, to follow the trail of clues and learn what has happened to Claire.

Mr. Jericho and Miss Wallace, as they formally address each other, work to decipher intercepts stolen by Claire and determine why she took them. Jericho is closely watched by an MI5 agent, Wigram (Jeremy Northam), who plays cat and mouse with him throughout the film. Meanwhile, U-boats are closing in on a convoy of thirty seven ships from America, giving the code-breakers less than four days to find a solution to reading the changed Shark cipher.

But someone else at Bletchley has a personal interest in the stolen intercepts, and may be responsible for Claire's disappearance.

Cast

- Dougray Scott as Tom Jericho

- Kate Winslet as Hester Wallace

- Saffron Burrows as Claire Romilly

- Jeremy Northam as Mr Wigram

- Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as Jozef 'Puck' Pukowski

- Tom Hollander as Guy Logie

- Donald Sumpter as Leveret

- Matthew Macfadyen as Cave

- Robert Pugh as Skynner

- Corin Redgrave as Admiral Trowbridge

- Nicholas Rowe as Villiers

- Edward Hardwicke as Heaviside

Production and premiere

The film was shot on location in England, Scotland and the Netherlands, with Bletchley Park mansion substituted by Chicheley Hall.[2] Other locations include the Great Central Railway, Loughborough and Tigh Beg Croft, near Oban, Scotland. Interiors were filmed at Elstree Film Studios.[3]

The film was produced by Mick Jagger of the Rolling Stones. Jagger makes a cameo appearance as an RAF officer at a dance. He also lent the film's design department a four-rotor Enigma encoding machine he owned to ensure the historical accuracy of one of the props. The festivities around the London premiere of the film are shown in the 2001 documentary Being Mick.

Reception

Critical reviews were largely positive, but there was criticism of the largely fictional storyline, which neither mentions the real codebreaker, Alan Turing, nor gives due credit to the Polish cryptanalysis foundation, the Biuro Szyfrów (Cipher Bureau). The film holds a 'fresh' 72% rating on review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, with the consensus reading, 'The well-crafted, twist-filled Enigma is a thinking person's spy thriller.'[4] Joe Leydon of Variety compared the film to works by Alfred Hitchcock, and remarked that, 'Overall, "Enigma" plays fair and square while generating suspense with its twisty plot. And while it requires a generous suspension of disbelief to accept a few action-hero gestures by the deeply troubled Jericho, Scott is persuasive and compelling enough as his complex character to drive the narrative.'[5]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film three stars and said, 'What I like about the movie is its combination of suspense and intelligence. If it does not quite explain exactly how decryption works (how could it?), it at least gives us a good idea of how decrypters work, and we understand how crucial Bletchley was—so crucial its existence was kept a secret for 30 years.'[6] On the other end, Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly was far less impressed, saying, 'The legend of how the British cracked the almighty Enigma must have sounded, on paper, like a nifty mathematical thriller—a historic WarGames set at the formative moment of the computer age. On screen, however, Enigma plays as if the scriptwriter, Tom Stoppard, and the director, Michael Apted, were themselves cryptographers; they seem to be making hunt-and-peck stabs at how to translate a tale of arcane numeric formulas into drama.'[7]

Historical accuracy

The film and, by association, the book have attracted criticism for their portrayal of the Polish role in Enigma decryption.[8] The historian Norman Davies argues that in the film the fictitious traitor turns out to be Polish, but only slight mention is made of the contributions of prewar Polish Cipher Bureau cryptologists to Allied Enigma decryption efforts,[9] but historically, the only known traitor active at Bletchley Park was British spy John Cairncross, who passed crucial secrets to the Soviet Union.[10]

The film hints that Dougray Scott's character, the brilliant Cambridge mathematician Thomas Jericho is the main code-breaker at Bletchley, equating him with Alan Turing, the original creator of the British Bombe, with the words of Mr Wigram, played by Jeremy Northam: "But what if someone tells them just how we do do it? Your thinking machine, clackity-clack, day and night, programmed with a menu, thanks to your big brain, that reduces the odds to just a few million-to-one until it locks on to the winning combination. There goes the war…” Of course Jericho is a totally fictional character, given that Turing was homosexual and only had a platonic relationship with his short-lived fiancé Joan Clarke, who knew about his sexual orientation. In reality it was unlikely that Turing was involved in code-breaking the Naval four-rotor Enigma Shark in 1943. Notes by Tony Sale do not mention Turing as the "someone in Bletchley Park [who] realised that Short Weather Signals were sent in the three wheel mode" and explained "the Central Met. Station had collated the U-Boat and other reports, [and] they broadcast a general synoptic in their own Met. Code", which used the standard International Met. Code further encoded using bigram tables, as discovered by Mr Archer from the Met. section of Bletchley Park.[11] According to Hugh Alexander, from June 1943 Joan Clarke, Mahon, Pendered and Noskwith were responsible for the whole of the cryptographic work until the end of the war.[12] Strangely, Joan Clarke is not present in the film as none of the team of cryptanalysts are female.

In the film, Cave, from Naval Intelligence, played by Matthew Macfadyen, mentioned Fasson and Grazier gave their lives to rescue the code books from a sinking submarine. There were actually three men who retrieved the books: First Lieutenant Anthony Fasson, Able Seaman Colin Grazier and 16-year-old Tommy Brown from the canteen. Fasson and Grazier did drown while attempting to retrieve electrical equipment from a U-boat U-559 (which Cave describes as its four-rotor enigma) on 30 October 1942, while Brown survived only to die in a house fire during shore-leave before the end of the war.[13][14][15] Fasson and Grazier were awarded the George Cross posthumously and Brown was awarded the George Medal.[16] Fictional character Cave states he was completing his last posting on a destroyer, in November '42, when the books were acquired.

There are historical records of the break in the ability of the British to decode the Naval enigma from 10 to 19 March 1943 when the third edition of the weather short signal codebook was deployed.[16]

The Katyn massacre, revealed after the discovery of mass graves of 4,500 Polish officers as depicted in the film, is a historical atrocity committed by Stalinist Russia in 1940. There is no evidence that details of the mass graves were intercepted by British intelligence, although it is possible. The first announcement of the discovery was broadcast by Radio Berlin on 13 April 1943.[17]

See also

- The Imitation Game - A 2014 biopic of Alan Turing and his involvement in cracking the Enigma.

- U-571 - A 2000 war film involving the capture of an Enigma machine.

- Cryptanalysis of the Enigma

- Ultra

- German submarine U-505 - A captured submarine - now on display in Chicago - that yielded an Enigma machine.

References

- "Enigma at Box Office Mojo". Retrieved 29 September 2010.

- Sleeve notes from DVD.

- IMDb: Locations for Enigma Retrieved 2013-04-01

- "Enigma". Rottentomatoes.com. 19 April 2002. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Leydon, Joe (24 January 2001). "Review: 'Enigma'". Variety. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Ebert, Roger. "Enigma Movie Review & Film Summary (2002) - Roger Ebert". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- "Enigma". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- "Norman Davies oskarża "Enigmę"". Filmweb.pl. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- Peter, Laurence. "How Poles cracked Nazi Enigma secret". BBC News. Retrieved 20 July 2009.

- "Britain betrayed: The Cambridge spy ring". BBC News. 13 September 1999. Retrieved 25 December 2017.

- Breaking Shark on the Short Weather Signals - The Breaking of German Naval Enigma by Tony Sale Retrieved 25 November 2017

- Update to Alan Turing: the Enigma by Andrew Hodges Part 5: Running Up, Turing.org Retrieved 25 November 2017

- The Documents recovered from U559 - at a price, The Breaking of German Naval Enigma by Tony Sale Retrieved 25 November 2017

- The boarding of U-559 changed the war – now both sides tell their story, The Guardian, 21 Oct 2017 Retrieved 25 November 2017

- Teen who rescued Enigma codes from sinking sub died in house fire without knowing the significance of his bravery, The Mirror, 27 Jan 2017 Retrieved 25 November 2017

- Allied Breaking of Naval Enigma, uboat.net Retrieved 25 November 2017

- The Katyn Wood Massacre, C N Trueman, The History Learning Site, 18 May 2015 Retrieved 25 November 2017