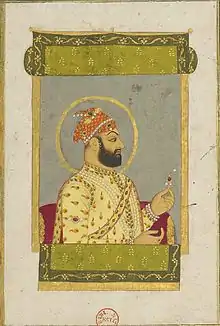

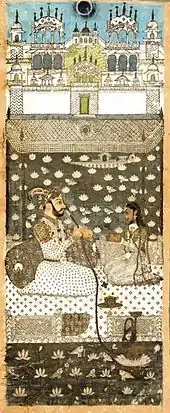

Farrukhsiyar

Abu'l Muzaffar Muin ud-din Muhammad Shah Farrukh-siyar Alim Akbar Sani Wala Shan Padshah-i-bahr-u-bar (Persian: ابو المظفر معید الدین محمد شاه فرخ سیر علیم اکبر ثانی والا شان پادشاه بحر و بر), also known as Shahid-i-Mazlum (Persian: شهید مظلوم), or Farrukhsiyar (Persian: فرخ سیر) (20 August 1685 – 19 April 1719), was the Mughal emperor from 1713 to 1719 after he murdered Jahandar Shah.[1] Reportedly a handsome man who was easily swayed by his advisers, he lacked the ability, knowledge and character to rule independently. Farrukhsiyar was the son of Azim-ush-Shan (the second son of emperor Bahadur Shah I) and Sahiba Nizwan.

| Farrukhsiyar | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mughal Emperor | |||||

| |||||

| 9th Mughal Emperor | |||||

| Reign | 11 January 1713 – 28 February 1719 | ||||

| Predecessor | Jahandar Shah | ||||

| Successor | Rafi ud-Darajat | ||||

| Born | 20 August 1685 Aurangabad, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Died | 19 April 1719 (aged 33) Delhi, Mughal Empire | ||||

| Burial | Humayun's Tomb, Delhi | ||||

| Spouse | Gauhar-un-Nissa Begum Bai Indira Kanwar Bai Bhip Devi | ||||

| Issue | Badshah Begum | ||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Timurid | ||||

| Father | Azim-ush-Shan | ||||

| Mother | Sahiba Niswan | ||||

| Religion | Islam | ||||

His reign saw the primacy of the Sayyid brothers, who became the effective power behind the facade of Mughal rule. Farrukhsiyar's frequent plotting led the brothers to depose him.

Early life

Muhammad Farrukhsiyar was born on 20 August 1685 (9th Ramzan 1094 AH) in the city of Aurangabad on the Deccan plateau. He was the second son of Azim-ush-Shan. In 1696, Farrukhsiyar accompanied his father on his campaign to Bengal. Mughal emperor Aurangzeb recalled his grandson, Azim-ush-Shan, from Bengal in 1707 and instructed Farrukhsiyar to take charge of the province. Farrukhsiyar spent his early years in the capital city of Dhaka (in present-day Bangladesh); during the reign of Bahadur Shah I, he moved to Murshidabad (present-day West Bengal, India).[2]

In 1712 Azim-ush-Shan anticipated Bahadur Shah I's death and a struggle for power, and recalled Farrukhsiyar. He was marching past Azimabad (present-day Patna, Bihar, India) when he learned of the Mughal emperor's death. On 21 March Farrukhsiyar proclaimed his father's accession to the throne, issued coinage in his name and ordered khutba (public prayer).[2] On 6 April, he learned of his father's defeat. Although the prince considered suicide, he was dissuaded by his friends from Bengal.[3]

War of succession

In 1712 Jahandar Shah (Farrukhsiyar's uncle) ascended the throne of the Mughal empire by defeating Farrukhsiyar's father, Azim-ush-Shan. Farrukhsiyar wanted revenge for his father's death and was joined by Hussain Ali Khan (the subahdar of Bengal) and Abdullah Khan, his brother and the subahdar of Allahabad.[4]

When they reached Allahabad from Azimabad, Jahandar Shah's military general Syed Abdul Ghaffar Khan Gardezi and 12,000 troops clashed with Abdullah Khan and Abdullah retreated to the Allahabad Fort. However, Gardezi's army fled when they learned about his death. After the defeat, Jahandar Shah sent general Khwaja Ahsan Khan and his son Aazuddin. When they reached Khajwah (present-day Fatehpur district, Uttar Pradesh, India), they learned that Farrukhsiyar was accompanied by Hussain Ali Khan and Abdullah Khan. With Abdullah Khan commanding the vanguard, Farrukhsiyar began the attack. After a night-long artillery fight, Aazuddin and Khwaja Ahsan Khan fled and the camp fell to Farrukhsiyar.[4]

On 10 January 1713 Farrukhsiyar and Jahandar Shah's forces met at Samugarh, 14 kilometres (9 mi) east of Agra in present-day Uttar Pradesh. Jahandar Shah was defeated and imprisoned, and the following day Farrukhsiyar proclaimed himself the Mughal emperor.[5] On 12 February he marched to the Mughal capital of Delhi, capturing the Red Fort and the citadel. Jahandar Shah's head, mounted on a bamboo rod, was carried by an executioner on an elephant and his body was carried by another elephant.[6]

Reign

Hostility with the Sayyid brothers

Farrukhsiyar defeated Jahandar Shah with the aid of the Sayyid brothers, and one of the brothers, Abdullah Khan, wanted the post of wazir (prime minister). His demand was rejected, since the post was promised to Ghaziuddin Khan, but Farrukhsiyar offered him a post as regent under the name of wakil-e-mutlaq. Abdullah Khan refused, saying that he deserved the post of wazir since he led Farrukhsiyar's army against Jahandar Shah. Farrukhsiyar ultimately gave in to his demand, and Abdullah Khan became prime minister.[7]

According to historian William Irvine, Farrukhsiyar's close aides Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran sowed seeds of suspicion in his mind that they might usurp him from the throne. Learning about these developments, the other Sayyid brother (Hussain Ali Khan) wrote to Abdullah: "It was clear, from the Prince's talk and the nature of his acts, that he was a man who paid no regard to claims for service performed, one void of faith, a breaker of his word and altogether without shame".[8] Hussain Ali Khan felt it necessary to act in their interests "without regard to the plans of the new sovereign".[9]

Campaign against Sikhs and execution of Banda Bahadur

Baba Banda Singh Bahadur was a Sikh leader who, by early 1700, had captured parts of the Punjab region.[10] Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I failed to suppress Bahadur's uprising.[11]

In 1714, the Sirhind faujdar (garrison commander) Zainuddin Ahmad Khan attacked the Sikhs near Ropar. In 1715, Farrukhisyar sent 20,000 troops under Qamaruddin Khan, Abdus Samad Khan and Zakariya Khan Bahadur to defeat Bahadur.[10] After an eight-month siege at Gurdaspur, Bahadur surrendered after he ran out of ammunition. Bahadur and his 200 companions were arrested and brought to Delhi; he was paraded around the city of Sirhind.[12]

Bahadur was put into an iron cage and the remaining Sikhs were chained.[13] The Sikhs were brought to Delhi in a procession with the 780 Sikh prisoners, 2,000 Sikh heads hung on spears, and 700 cartloads of heads of slaughtered Sikhs used to terrorise the population.[14][15] When Farrukhsiyar's army reached the Red Fort, the Mughal emperor ordered Banda Bahadur, Baj Singh, Bhai Fateh Singh and his companions to be imprisoned in Tripolia.[16] After three months of confinement,[17] On 19 June 1716 Farrukhsiyar had Bahadur and his followers executed, despite the wealthy Khatris of Delhi offering money for his release.[18] Banda Singh's eyes were gouged out, his limbs were severed, his skin removed, and then he was killed.[19]

Trade concession

In 1717, Farrukhsiyar issued a farman giving the British East India Company the right to reside and trade in the Mughal Empire. They were allowed to trade freely, except for a yearly payment of 3,000 rupees. This was because William Hamilton, a surgeon associated with the company cured Farrukhsiyar of a disease.[20] The company was given the right to issue dastak (passes) for the movement of goods, which was misused by company officials for personal gain.[21]

Final struggle with the Sayyids

By 1715, Farrukhsiyar had given Mir Jumla III the power to sign documents on his behalf: "The word and seal of Mir Jumla are my word and seal". Mir Jumla III began approving proposals for jagirs and mansabs without consulting Syed Abdullah, the prime minister.[22] Syed Abdullah's deputy Ratan Chand accepted bribes for him to do work and was involved in revenue farming, which was forbidden by the Mughal emperor. Taking advantage of the situation, Mir Jumla III told Farrukhsiyar that the Sayyids were unfit to hold office and accused them of insubordination. Hoping to depose the brothers, Farrukhsiyar began making military preparations and increased the number of soldiers under Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran.[23]

After Syed Hussain learned about Farrukhsiyar's plans, he felt that their position could be cemented by controlling "important provinces". He asked to be appointed viceroy of the Deccan, instead of Nizam ul Mulk; Farrukhsiyar refused, transferring him to the Deccan instead. Fearing attack by Farrukhsiyar's supporters, the brothers began making military preparations. Although Farrukhsiyar initially considered giving the task of crushing the brothers to Mohammad Amin Khan (who wanted the position of prime minister in return), he decided against it because removing him would be difficult.[24]

Arriving at the Deccan, Syed Hussain made a treaty with Maratha ruler Shahu I in February 1718. Shahu was allowed to collect sardeshmukhi in Deccan, and received the lands of Berar and Gondwana to govern. In return, Shahu agreed to pay one million rupees annually and maintain an army of 15,000 horses for the Sayyids. This agreement was reached without Farrukhsiyar's approval,[25] and he was angry when he learned about it: "It was not proper for the vile enemy to be overbearing partners in matters of revenue and government."[26]

Appointments

Farrukhsiyar appointed Sayid Abdullah Khan as chief minister and placed Muhammad Baqir Mutamid Khan in charge of the Exchequer. The title of bakshi was first conferred on Hussain Ali Khan (with the titles of Umdat-ul-Mulk, Amir-ul-umara and Bahadur Firuz Jung) and then to Chin Qilich Khan and Afrasayab Khan Bahadur.[27]

The following were governors of the provinces; the governor of South India was Chin Qilich Khan, who appointed deputy governors:[28][29][30]

| North India | South India | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Governor/Chief Minister | Province | Deputy governor |

| Agra | Shams ud Daula Shah Nawaz Khan | Berar | Iwaz Khan |

| Ajmer | Syed Muzaffar Khan Barha | Bidar | Amin Khan |

| Allahabad | Khan Jahan | Bijapur | Mansur Khan |

| Awadh | Sarbuland Khan | Burhanpur | Shukrullah Khan |

| Bengal | Farkhunda Bakht | Hyderabad | Yusuf Khan |

| Bihar | Syed Hussain Ali Khan | Karnataka | Saadatullah Khan |

| Delhi | Muhammad Yar Khan | ||

| Gujarat | Shahamat Khan | ||

| Kabul | Bahadur Nasir Jang | ||

| Kashmir | Saadat Khan | ||

| Lahore | Abdus Samad Khan | ||

| Malwa | Raja Jai Singh of Amber | ||

| Multan | Qutb-ul-Mulk | ||

| Orissa | Murshid Quli Khan | ||

Deposition

To fight the Sayyids, Farrukhsiyar summoned Ajit Singh, Nizam-ul-Mulk and Sarbuland Khan to the court with their troops; the armies' combined strength was 80,000. He did not summon Mir Jumla III and Khan Dauran, since the former failed in a campaign in Bihar and he felt that the latter had conspired with the Sayyid brothers to depose him. However, Syed Abdullah's troop strength was about 3,000. According to Satish Chandra, Farrukhsiyar could have defeated him with the help of the nobles; he did not do it, since he believed it would be difficult to get rid of them afterwards. He appointed Muhammad Murad Kashmiri as the new wazir (prime minister), replacing Syed Abdullah. Kashmiri was a notorious for having sexual relationships with boys; this angered the nobles, who resigned from his court. Ajit Singh, alienated because he was removed from Gujarat for oppression, also sided with the Sayyids.[31] By the end of 1718, when Syed Hussain began his march from the Deccan with 10,000 troops under Peshwa Balaji Vishwanath, Farrukhsiyar could only secure Jai Singh II's support. Syed Hussain's excuse for marching towards Delhi was to bring a son of the Maratha ruler Shahu to him.[32]

With the support of Mohammad Amin Khan, Ajit Singh and Khan Dauran, Syed Hussain fought Farrukhsiyar; after a night-long battle, he was deposed on 28 February 1719.[33] The Sayyid brothers placed Rafi ud-Darajat on the throne. Farrukhsiyar was imprisoned in Tripolia and blinded.[34] During his imprisonment he was served bitter, salty food and deprived of water. He passed the time by reciting verses from the Quran.[35] Although Farrukhsiyar tried to bribe jailer Abdullah Khan Afghan with the command of 7,000 troops if he released him and brought him to Jai Singh II, the bribe was refused.[36] On 19 April 1719 he was strangled by unknown assailants and buried in Humayun's Tomb beside his father, Azim-ush-Shan.[37]

Personal life

Family

Farrukhsiyar's first wife was Fakhr-un-nissa Begum, also known as Gauhar-un-nissa, the daughter of Mir Muhammad Taqi (known as Hasan Khan and then Sadat Khan). Taqi, from the Persian province of Mazandaran, married the daughter of Masum Khan Safawi; if she was the mother of Fakhr-un-nissa, this would account for her daughter's selection as the prince's wife.[38]

His second wife was Bai Indira Kanwar, the daughter of Maharajah Ajit Singh. [39] She married Farrukhsiyar on 27 September 1715, during the fourth year of his reign, and they had no children. After Farrukhsiyar's deposition and death she left the imperial harem on 16 July 1719, she returned to her father with her property and lived her remaining years in Jodhpur.[40]

Farrukhsiyar's third wife was Bai Bhup Devi, daughter of Jaya Singh (the raja of Kishtwar, who had converted to Islam and received the name of Bakhtiyar Khan). After Jaya Singh's death he was succeeded by his son, Kirat Singh. In 1717, in response to a message from the Shaykh al-Islām, her brother Kirat Singh sent her to Delhi with her brother Mian Muhammad Khan. Farrukhsiyar married her, and she entered the imperial harem on 3 July 1717.[40][41]

Titles

His full name was Abul Muzaffer Muinuddin Muhammad Farrukhsiyar Badshah.[42] Posthumously, he was known as "Shahid-i-marhum" (the martyr received with mercy).[43]

Coinage

On coins issued during Farrukhsiyar's reign, the following phrase was inscribed: "Sikka zad az fazl-i-Haq bar sim o zar/ Padshah-i-bahr-o-bar Farrukhsiyar" (By the grace of the true God, struck on silver and gold, the emperor of land and sea, Farrukhsiyar).[43] There are 116 coins from his reign on display at the Lahore Museum and the Indian Museum in Kolkata. The coins were minted in Kabul, Kashmir, Ajmer, Allahabad, Bidar and Berar.[43]

Legacy

The town of Farrukhnagar in Gurgaon district, 32 kilometres (20 mi) south of Delhi, was named for him. During his reign, he built a Sheesh Mahal (palace) and a Jama Masjid (mosque) there.

The town of Farrukhabad in Uttar Pradesh was also named after him.

Farrukhsiyar | ||

| Preceded by Jahandar Shah |

Mughal Emperor 1713–1719 |

Succeeded by Rafi Ul-Darjat |

Notes

- Sen, Sailendra (2013). A Textbook of Medieval Indian History. Primus Books. p. 193. ISBN 978-93-80607-34-4.

- Irvine, p. 198.

- Irvine, p. 199.

- Asiatic Society of Bengal, p. 273.

- Asiatic Society of Bengal, p. 274.

- Irvine, p. 255.

- Tazkirat ul-Mulk by Yahya Khan p.122

- Irvine, p. 282.

- Irvine, p. 283.

- "Marathas and the English Company 1707–1800". San Beck. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- Richards, p. 258.

- Singha, p. 15.

- Duggal, Kartar (2001). Maharaja Ranjit Singh: The Last to Lay Arms. Abhinav Publications. p. 41. ISBN 9788170174103.

- Johar, Surinder (1987). Guru Gobind Singh. The University of Michigan: Enkay Publishers. p. 208. ISBN 9788185148045.

- Sastri, Kallidaikurichi (1978). A Comprehensive History of India: 1712–1772. The University of Michigan: Orient Longmans. p. 245.

- Singha, p. 16.

- Singh, Ganda (1935). Life of Banda Singh Bahadur: Based on Contemporary and Original Records. Sikh History Research Department. p. 229.

- Irvine, p. 319.

- Singh, Kulwant (2006). Sri Gur Panth Prakash: Episodes 1 to 81. Institute of Sikh Studies. p. 415. ISBN 9788185815282.

- Samaren Roy (May 2005). Calcutta: Society and Change 1690–1990. iUniverse. p. 29. ISBN 978-0-595-34230-3.

- Vipul Singh, Jasmine Dhillon, Gita Shanmugavel. History and Civics. Pearson India. p. 73. ISBN 978-81-317-6320-9.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Chandra, p. 476.

- Chandra, p. 477.

- Chandra, p. 478.

- Ram Sivasankaran (22 December 2015). The Peshwa: The Lion and the Stallion. Westland. p. 5. ISBN 978-93-85724-70-1.

- Chandra, p. 481.

- Irvine, p. 258.

- Irvine, p. 261.

- Irvine, p. 262.

- Irvine, p. 263.

- Chandra, p. 482.

- Chandra, p. 483.

- William Irvine. p. 379-418.

- Irvine, p. 390.

- Irvine, p. 391.

- Irvine, p. 392.

- Irvine, p. 392–93.

- Irvine, p. 400-1.

- Irvine, p. 400.

- Irvine, p. 401.

- Proceedings – Punjab History Conference – Volumes 29-30. Punjabi University. 1998. p. 85.

- Irvine, p. 398.

- Irvine, p. 399.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Farrukhsiyar. |

- Irvine, William, The Later Mughals, Low Price Publications, ISBN 81-7536-406-8

- Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. (Bishop's College Press)47. 18 August 2009.

- Fisher, Michael H. (1 October 2015), A Short History of the Mughal Empire, I.B.Tauris, ISBN 978-0-85772-976-7

- Singha, H.S. (1 January 2005), Sikh Studies, Book 6, Hemkunt Press, ISBN 978-81-7010-258-8

- Chandra, Satish (July 2007), Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughal Empire, Har Anand Publications Pvt Ltd., ISBN 978-81-241-1269-4