Fernando de la Rúa

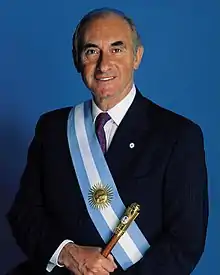

Fernando de la Rúa Bruno (15 September 1937 – 9 July 2019) was an Argentine politician and a member of the Radical Civic Union (UCR) political party who served as President of Argentina from 10 December 1999 to 21 December 2001. De la Rúa was born in Córdoba; he entered politics after graduating with a degree in law. He was elected senator in 1973 and unsuccessfully ran for the office of Vice President as Ricardo Balbín's running mate the same year. He was re-elected senator in 1983 and 1993, and as deputy in 1991. He unsuccessfully opposed the pact of Olivos between President Carlos Menem and party leader Raúl Alfonsín, which enabled the 1994 amendment of the Argentine Constitution and the re-election of Menem in 1995.

Fernando de la Rúa | |

|---|---|

Fernando de la Rúa in 1999 | |

| President of Argentina | |

| In office 10 December 1999 – 21 December 2001 | |

| Vice President | Carlos Álvarez (1999–2000) None (2000–2001) |

| Preceded by | Carlos Menem |

| Succeeded by | Adolfo Rodríguez Saá (interim) |

| President of the National Committee of the Radical Civic Union | |

| In office 10 December 1997 – 10 December 1999 | |

| Preceded by | Rodolfo Terragno |

| Succeeded by | Raúl Alfonsín |

| 1st Chief of Government of Buenos Aires | |

| In office 7 August 1996 – 10 December 1999 | |

| Deputy | Enrique Olivera |

| Preceded by | Jorge Domínguez (appointed mayor) |

| Succeeded by | Enrique Olivera |

| National Senator | |

| In office 10 December 1993 – 7 August 1996 | |

| Constituency | City of Buenos Aires |

| In office 10 December 1983 – 10 December 1987 | |

| Constituency | City of Buenos Aires |

| In office 25 May 1973 – 24 March 1976 | |

| Constituency | City of Buenos Aires |

| National Deputy | |

| In office 10 December 1991 – 10 December 1993 | |

| Constituency | City of Buenos Aires |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Fernando de la Rúa Bruno 15 September 1937 Córdoba, Argentina |

| Died | 9 July 2019 (aged 81) Loma Verde, Argentina |

| Resting place | Pilar Memorial Cemetery |

| Nationality | |

| Political party | Radical Civic Union |

| Other political affiliations | Alliance |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children | Antonio, Agustina, Fernando. |

| Alma mater | National University of Córdoba |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Signature | |

De la Rúa was the first chief of government of Buenos Aires to be elected by popular vote, a change introduced by the amendment of the Constitution. He expanded the Buenos Aires Underground, adding new stations to Line D, starting the expansion of Line B, and establishing Line H. He established Roberto Goyeneche Avenue and the city's first bicycle path.

In 1999, De la Rúa was elected president after running on the Alliance ticket, a political coalition of the UCR and the Frepaso. He was opposed by the Peronist unions and his vice president Carlos Álvarez resigned after denouncing bribes in the Senate. The economic crisis that began during Menem's administration worsened and by the end of 2001 led to a banking panic. The government established the Corralito to limit bank withdrawals. De la Rúa called a state of emergency during the December 2001 riots. Following his resignation on 20 December, the Argentine Congress appointed a new president. After leaving office, De la Rúa retired from politics and faced legal proceedings for much of the remainder of his life until his death in 2019.

Early life

Fernando de la Rúa was born on September 15, 1937, in the city of Córdoba, the son of Antonio de la Rúa and Eleonora Felisa Bruno.

The De la Rúa family was closely linked to Argentine politics in more than one province and several of its members had previously been members of the Unión Cívica Radical. His father was of Galician descent and came from Santiago del Estero, having settled in the province of Córdoba to study law; his mother was the daughter of Italian immigrants.

De la Rúa attended Olmos elementary school, and completed his secondary studies at the General Paz Military High School, maintaining very high averages of 9.53 in the first year and 9.92 in the last, which allowed him to be a standard-bearer.

He manifested his initial political leanings in that period as an opponent of the government of Juan Domingo Perón and the justicialist movement, on which he wrote satires under the pseudonym "Lauchín." Those who knew him in his teens described him as an outgoing and smiling person, with a very different personality from the serious and moderate profile that he would maintain throughout his political career. He joined radicalism when he came of age, in 1955, approximately when the September 1955 coup occurred that overthrew Perón and established a military dictatorship, which outlawed justicialism. De la Rúa remained linked to the most anti-Peronist and right-wing sectors of the UCR, and when the party split in 1957, he remained in the Unión Cívica Radical del Pueblo (UCRP), staying that way until it again obtained the title «Unión Cívica Radical »In June 1972. In addition to his radical affiliation, from his childhood De la Rúa was fervently Catholic and had an active participation in religious groups such as the Catholic Youth Movement and the Catholic Youth of Córdoba.

Although he initially intended to study medicine, he eventually resolved to become a lawyer, largely at the instigation of his father. He completed his career quickly and was received with a medal of honor at the National University of Córdoba in 1958, at the young age of 21.

He married a Buenos Aires socialite, Inés Pertiné, in 1970; they had three children, including Antonio de la Rúa.

Early political activity

He was elected senator in the March 1973 general elections, defeating the Peronist Marcelo Sánchez Sorondo.[1] He was the only politician from the Radical Civic Union (UCR) who could defeat the Peronist candidate in his administrative division. The Buenos Aires radicalism celebrated the result profusely, ending with a press conference during which De la Rúa thanked the radical militancy for supporting him and the citizens who voted for him without being radical, stating: «Today Buenos Aires has proven to be the capital of the liberation, and the change is us ». Although he acknowledged the defeat, Sánchez Sorondo accused De la Rúa and the UCR in a later analysis of having "served a new trial by Unión Democrática," referring to the confluence of disparate forces with the sole purpose of defeating Peronism.

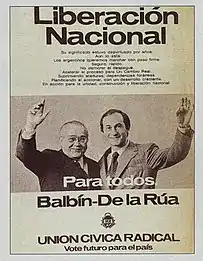

General elections of September 1973

The elected president Héctor José Cámpora and his vice president resigned a few months later, leading to the call to new elections. Ricardo Balbín ran for president in the September general elections, with De la Rúa as his running mate for the post of vice president. Initially, a consensus was sought between the National Line, the majority internal faction headed by Balbín, and the Movement for Renewal and Change led by Raúl Alfonsín to present a formula that would represent the two factions. However, Alfonsinism made the intervention of the radical committees of the Federal Capital, Entre Ríos, Santa Fe and Tucumán a condition, which was rejected by the party leadership.

The elections took place on September 23 with an overwhelming victory for FREJULI, resulting in Perón elected for a third non-consecutive term with 61.85% of the votes over Balbín's 24.42%, a difference of 37.43 points. that has not been surpassed in Argentine electoral history.

Senator for Federal Capital (1973-1976)

De la Rúa served his first term as National Senator on behalf of the Federal Capital from May 25, 1973 until the coup on March 24, 1976, which involved the dissolution of Congress. At the time of his inauguration, he promised to support laws that were "of a popular nature", while ensuring that he would seek to represent a "democratic control" over the ruling party. On May 27, two days after taking office, he voted in favor of the release of political prisoners, fulfilling one of his main campaign promises.

During his first term as senator he was one of the main leaders of the radical opposition to the successive and brief Peronist administrations, ending with the government of María Estela Martínez de Perón (1974-1976). Of particular note in his parliamentary management is the drafting and defense of the Presidential Acefalía Law, which was approved on July 11, 1975 after an intense debate and which in 2001 would be used to replace him as president after his resignation.

De la Rúa was removed from the Congress during the 1976 Argentine coup d'état. He left politics and worked as a lawyer for the firm Bunge y Born.

Pre-presidential candidacy 1983

The National Reorganization Process ended in 1983. De la Rúa intended to run for president but lost in the primary elections of the UCR to Raúl Alfonsín, who was elected in the general election. De la Rúa ran for the post of senator instead, defeating the Peronist Carlos Ruckauf. He ran for re-election as senator in 1989 but, despite his electoral victory, the electoral college voted for the Peronist Eduardo Vaca.[2] De la Rúa was elected deputy in 1991 and returned to the senate in 1993. President Carlos Menem, elected in 1989, wanted to amend the constitution to allow him to run for re-election in 1995, which was opposed by the UCR.

Mayor of Buenos Aires

The Buenos Aires elections for the autonomous authorities took place on June 30, 1996. De la Rúa's candidacy for the head of government took place in an extremely unfavorable context for radicalism, in clear decline after the overwhelming defeat in the elections of 1995, in which its presidential candidate, Horacio Massaccesi, placed third behind the recently founded FREPASO.

As in previous elections, De la Rúa maintained a speech with strong emphasis on denouncing the prevailing political corruption, both in the Menem government and in the Domínguez administration, whom he defined as a "de facto mayor" after almost two years after the constitutional reform was carried out without the autonomous institutions having been normalized. He committed himself mainly to strengthening institutional transparency and seeking to reduce the city's debt.

De la Rúa worked on the expansion of the Buenos Aires Underground. The first stations of the extended Line D, Olleros and José Hernández, were opened in 1997,[3] Juramento was opened in 1999,[4] and Congreso de Tucumán in 2000. He also started the works to extend the Line B.[5] Carlos Menem started to transfer the control and financing of the underground system to the city, but the 2001 economic crisis halted the process.

The former mayor Domínguez intended to expand the Pan-American Highway into Saavedra, but the project met widespread opposition. De la Rúa reformulated the project and built an avenue instead of a highway, which was accepted. The avenue was named Roberto Goyeneche. He also restarted a project to build the Cámpora Highway linking Dellepiane Avenue with the Riachuelo, and established the first non-recreational bikeway in Buenos Aires at Avenida del Libertador.

Road to the presidency

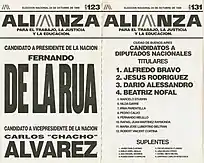

The year after his inauguration as head of government, in August 1997, the Alliance for Work, Justice and Education was formed, with several moderate left and center political parties, the main ones being the Unión Cívica Radical and the Frente Solidarity Country (Frepaso). The main objective of the Alliance was to create common lists in as many districts as possible for the legislative elections of the same year, and also to challenge the Justicialismo for power in the 1999 presidential elections. A good part of those aspirations were fulfilled when, With joint lists in 14 districts (including the Capital and the Province of Buenos Aires) in October 1997 the UCR and Frepaso triumphed with 45 percent of the votes in the entire country, causing the first national electoral defeat of the Justicialista Party since 1985.

Fernando De la Rúa achieved victory in the open internship[6] in November 1998, reaching 62% of the votes against 38% for Frepaso throughout the country. Fernando de la Rúa consecrated as presidential candidate, the leader of Frepaso, Carlos Álvarez, decided to accompany him as a candidate for vice president to strengthen the unity of the coalition.

General elections of 1999

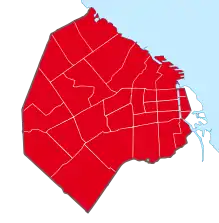

Fernando De la Rúa, candidate of the Alliance, was elected president in the elections of October 24, 1999, and the justicialist party lost the majority in the Chamber of Deputies. The Alliance and its formula De la Rúa-Álvarez obtained 48.5% of the votes, against 38.09% for the Peronist Eduardo Duhalde-Ramón Ortega binomial. In third place, with 10.09% of the votes, appeared the former Minister of Economy Domingo Cavallo.

One of the successes of the electoral campaign was De la Rúa's television advertising campaign, in which he pronounced the phrase "They say I'm boring ..." with which he would later be related. This publicity sought to contrast the presidential candidate with the frivolity that the public perceived in the Menem government. The electoral campaign was led by Ramiro Agulla, David Ratto (Raúl Alfonsín's publicist in the 1983 elections) and Antonio de la Rúa, the latter son of Fernando De la Rúa himself.

Presidency

Inauguration

On December 10, 1999, Fernando De la Rúa was sworn in as President of the Argentine Nation in the Congress of the Argentine Nation and then went to receive from his predecessor Carlos Menem the Presidential Band of Argentina. In the streets, people crowded into the Plaza de Mayo, threw little pieces of paper at the presidential car and interrupted traffic.

Domestic policy

In the first days of his presidency, De la Rúa sent a bill to the Congress to request a federal intervention in the province of Corrientes. The province had a high level of debt, and organizations of piqueteros blocked roads to make demonstrations. There were two interim governors disputing power. The bill was immediately approved.[7] The intervenor selected for the task was Ramón Mestre.[8]

The Peronist unions opposed De la Rúa and held seven general strikes against him. He sent a bill known as the labour flexibility law to deregulate labor conditions, attempting to reduce the political influence of unions, to the Congress. This project was opposed by the PJ and was changed from the original draft. It was finally approved but Álvarez said several legislators were bribed to support the bill. Álvarez asked for the removal of the labor minister Alberto Flamarique, but De la Rúa instead promoted him to be his personal secretary.

Álvarez resigned the following day and the political scandal divided the coalition. Several deputies who initially supported De la Rúa switched to the opposition. Alfonsín tried to prevent breakup of the UCR. Some months later, it was proposed that Álvarez return to the De la Rúa government as the Chief of the Cabinet of Ministers. Álvarez initially supported the idea but De la Rúa opposed it. Cavallo was also proposed for the office before he was appointed Minister of Economy. De la Rúa intended to include the Frepaso in the new cabinet but to exclude Álvarez himself because he still resented the latter's resignation. The negotiations failed and the new cabinet included no Frepaso politicians, but the Alliance was still working as a coalition in the Congress. It also included several radical politicians from Alfonsín's internal faction. The new Chief of Cabinet was Chrystian Colombo, who mediated between Alfonsín and the president.

The PJ won the 2001 midterm election by 40% to 24%, giving it a majority in both chambers of the Congress. However, the abstention rate and several forms of protest votes combined reached 41%, the highest in Argentine history, as a consequence of the popular discontent with the two main parties. Even the few candidates of the Alliance who won at their districts, such as the radical Rodolfo Terragno in Buenos Aires, did so with political platforms against De la Rúa's administration.

Foreign policy

In 1999, after the victory of Fernando De la Rúa in the presidential elections, Adalberto Rodríguez Giavarini was appointed Chancellor on December 10 of that year.

Regarding regional integration, Rodríguez Giavarini praised Mercosur, which made it possible to multiply Argentina's exports to its partners by four and was in favor of the formation of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (FTAA).

The relationship with The United States was classified as "solid and strong", following the policy developed by Di Tella. The first year of De la Rúa's presidency coincided with the last year of Bill Clinton's presidency of the United States. Ricardo López Murphy, Minister of Defense at the time, met William Cohen, U.S. Secretary of Defense, in a summit of ministers that took place in Brazil in 2000. Both countries agreed to share classified information and to hold joint operations against terrorism.[9]

George W. Bush took office as President of the United States in January 2001, and changed American policy towards countries in financial crises. His treasury secretary, Paul H. O'Neill, a critic of financial aid, said, "We're working to find a way to create a sustainable Argentina, not just one that continues to consume the money of the plumbers and carpenters in the United States who make $50,000 a year and wonder what in the world we're doing with their money". The September 11 attacks occurred a few months later, and the U.S. focused its foreign policy on the War on Terror against countries suspected of harboring terrorist organizations. As a result, the U.S. gave no further financial aid to Argentina. This policy was confirmed after an interview of Bush with the Brazilian president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, who confirmed Brazil would not be affected by the Argentine crisis.

With regard to the Malvinas issue, he differed from the position of his predecessor in office, Guido Di Tella, who had proposed a policy of "seduction" towards the islanders. Rodríguez Giavarini declared that the islands were "territory of Argentina" so that "we are completely unaware of that government" (referring to the island's government). In January 2000 he held a meeting with the British Foreign Minister, Robin Cook, who stated that "there are many agreements between the United Kingdom and Argentina and only one significant disagreement: the Malvinas."

Economic policy

By the end of 1999, when Fernando de la Rúa took office, it was clear that the situation could not be maintained without taking some substantive measure. The country's most serious problem was the heavy burden of public debt that had accumulated as a consequence of the high fiscal deficits that had dragged on since 1995. The three possible paths were the following:

- Cause a forced "dollarization" of the economy, to eliminate uncertainty about the system of fixed exchange between the peso and the dollar. This option was launched by the Government of Menem in January 1999, although the project finally did not prosper.

- Defend convertibility to the letter, reducing public spending, restructuring the debt and applying measures that favor the competitiveness of Argentine companies, either by restricting imports or eliminating taxes and social charges. Competitiveness could also be improved by referencing the value of the peso to other currencies in addition to the dollar (such as the euro or the real), which would provide greater room for maneuver.

- Devalue the peso in order to finance fiscal deficits with monetary issuance and promote Keynesian policies that would favor a rapid recovery of the economy. Although this measure seemed at first glance the most effective, it was the most traumatic of all, since it required the total or partial repeal of the Convertibility Law (which would affect the credibility of the country), declare almost all public and private debt in default, forcibly "pesify" the economy and risk causing a sharp depreciation of the currency with a resurgence of inflation.

De la Rúa's first Minister of Economy was the progressive José Luis Machinea, who was proposed by Alfonsín and Álvarez. Menem had left a deficit of 5 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) points that Machinea tried to compensate with higher taxes to people with the highest incomes, and a reduction of the highest retirement pensions. The deficit was reduced but the crisis continued. The scandal over the labor law and the resignation of Álvarez increased the country's risk, and made Argentina's access to international credit more difficult. The government negotiated a US$38 billion International Monetary Fund (IMF) line of credit to prevent a default and allow the economy to grow again. Machinea also proposed appointing former minister Cavallo as the new President of the Central Bank of Argentina. However, Machinea was unable to achieve the levels of austerity negotiated with the IMF and resigned a few days later.

The Minister of Defense Ricardo López Murphy became the new Minister of Economy. During the election camapain, De la Rúa had promised not to appoint him to that ministry, but with the ongoing crisis he did not want to risk problems caused by a temporary lack of minister. López Murphy announced a stricter austerity plan, with reduction to the health and education budgets. His plan was rejected by street demonstrations and the Frepaso, so De la Rúa declined it. Murphy resigned after being minister for 16 days.

De la Rúa appointed Cavallo, who had served under Menem and had established the convertibility plan. He was supported by the PJ, Carlos Álvarez, and the financial groups, but he was rejected by the rest of the UCR. The government announced it would retain the convertibility plan and that there would be no devaluation or sovereign default. Cavallo proposed several bills; De la Rúa sent them to the Congress and they were approved. The "superpowers law" authorized the chief of government to modify the national budget without the intervention of the Congress. There was a new tax on bank operations and more products attracted value-added tax. The wages of national customs workers were increased and some industries benefited from tax exemptions. The Megacanje was a negotiation to delay the payment of foreign debt in exchange for higher interest rates. However, internal debt was still a problem because the provinces, especially Buenos Aires, were nearing default. This led to conflicts between Cavallo and the provincial governors. Congress approved a bill for a "Zero deficit" policy to prevent further increases of debt and to work only with money from tax revenue. There was a banking panic in November; the government reacted by introducing the "corralito", which prevented people from withdrawing cash from banks. It was initially a temporary measure. The IMF refused to send the monthly payment for the line of credit approved at the beginning of the year because the government had not stuck to the "zero deficit" policy.

Riots and resignation

The mismanagement of Fernando De la Rúa caused that in the legislative elections of October 2001 the opposition Justicialist Party won the majority of both houses of Congress and that the members of the Radical Civic Union were upset with their leader, to such a degree to get away from it. Popular support had been lost.

The crisis worsened and by 19 December 2001, riots and looting broke out at several points in the country. De la Rúa announced in a cadena nacional (national network broadcast) that he had established a state of emergency.[10] The riots continued; his speech was followed by increased protests, the cacerolazos, which caused 27 deaths and thousands of injuries. Cavallo resigned at midnight the same day, and the rest of the cabinet followed suit.

There was increased looting on 20 December, both in Buenos Aires and the Conurbano. The cacerolazos continued; large groups of people started demonstrations calling for the government's resignation. The unions—first the CTA and then the CGT—began general strikes against the state of emergency. Most of the UCR withdrew their support for De la Rúa, so he asked the PJ to create a government coalition. The PJ refused, and De la Rúa resigned from government.

At 7:30 p.m. De la Rúa thanked the presidential photographer and asked him for a last photo in his office, here he signed Decree 1682/2001 that framed the police action under internal commotion, implicitly authorizing the repression under his responsibility. With a sob, he expressed his resignation in a manuscript addressed to Ramón Puerta and left it on his desk, then picked up a Constitution of the Argentine Nation and left his office.

He went up to the terrace by a private elevator where a Sikorsky S-76 Spirit helicopter awaited him without landing, the President ran towards him and boarded with the help of his guards. The image of the aircraft leaving the building in the hot and cloudy sunset, with the leader of the country fallen and under a shout of insults, was forever captured in the memory of Argentines.

On December 21, De la Rúa arrived at Casa Rosada at 9:00 a.m., he was still President because the Legislative Assembly had not approved his resignation, he walked in and spent two hours: he met with Spanish President Felipe González and signed his last decree, where it repealed the state of siege.

Succession

Because Vice President Carlos Álvarez had already resigned, Ramón Puerta assumed the presidency provisionally until December 23 when the Congress convened to appoint a new president. Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, governor of San Luis Province, was in office until December 30 while calling for new presidential elections. Renewed demonstrations forced him to resign as well, and Eduardo Camaño, President of the Chamber of Deputies, governed on an interim basis until January 2, 2002, when the Legislative Assembly elected Eduardo Duhalde as president, holding office until May 2003. He was able to complete De la Rúa's term of office.[11]

For Fernando De la Rúa, the Peronist sector led by Eduardo Duhalde and the same radicalism that responded to Raúl Alfonsín staged a coup. Such version of events is shared, among others, by Darío Lopérfido and Domingo Cavallo.

Later life and death

De la Rúa withdrew from political life and avoided appearances or statements, even regarding the legal cases against him. One of them refers to the events that took place at the end of his mandate, during which 30 people died in different parts of the country. Enrique Mathov, the former Secretary of Security, accused De la Rúa of having ordered the repression. De la Rúa was also prosecuted in a case in which he is accused of bribing legislators to get the approval of the 2000 Labor Reform.

Public image

.jpg.webp)

De la Rúa started to work in politics from a very young age. He was nicknamed "Chupete" (Spanish: "Pacifier") because of this; the nickname was still employed when he grew up. During Carlos Menem's administration he was perceived as a serious and formal politician, in stark contrast with Menem's style. De la Rúa took advantage of this perception during the electoral campaign of 1999. When he became president and the economic crisis worsened, he was perceived as a weak and tired man who was unable to react to the crisis. He was perceived as a man without leadership skills who could not make use of his presidential authority.[12] De la Rúa thought that the parody of him by the television comedian Freddy Villarreal helped to establish that image.[13] He sought to change his image by appearing on the television comedy show El show de Videomatch, but his appearance on the program backfired. He confused the names of the show and that of the host Marcelo Tinelli's wife.

After De la Rúa's participation ended, Tinelli began to close the program; De la Rúa could be seen seeking an exit from the set in the background. The aforementioned popular image of De la Rúa was further magnified when he was hospitalized for peripheral artery disease caused by high blood cholesterol. Although it is a standard, simple medical intervention, the medic told the press De la Rúa suffered from arteriosclerosis, which is usually linked with a lack of speed and reflexes.

Death

The former head of state's health status had deteriorated greatly during 2019. He had been admitted to the Austral Hospital on January 1 of that year for coronary and kidney problems that kept him in intensive care for four weeks. Under these circumstances they had to perform a tracheostomy. After 28 days he was discharged and underwent rehabilitation treatment at the Fleni Sanatorium in the town of Loma Verde.

Fernando de la Rúa died at 7:10 a.m. on Tuesday, July 9, 2019 at the age 81.[14]

He received a state funeral in Congress before a private burial the following day.[15] President Mauricio Macri decreed three days of national mourning.

His remains were buried in the Pilar Memorial Cemetery.

Legacy

The image of the resigning President leaving the Casa Rosada by helicopter was forever etched in the memory of Argentines. This fact also affected the political party of the former president, losing most of the subsequent elections, weakening the Radical Civic Union in the face of a rising Peronism, which, in the absence of its classic rival, was divided into two fronts.

Honours

.svg.png.webp)

Decorations

| Award or decoration | Country | Date | Note | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collar of the Order of Merit | 18 May 2000 | [16] | ||

| Grand Collar of the Order of Boyaca | 4 October 2000 | [17] | ||

| Knight Grand Cross with collar of the Order of Merit of the Italian Republic | 7 March 2001 | [18] | ||

| Collar of the National Order of Merit | 15 May 2000 | [19] | ||

| Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry | 14 November 2001 | [20] | ||

| Grand Cross (or 1st Class) of the Order of the White Double Cross | 2001 | [21] | ||

| Knight of the Collar of the Order of Isabella the Catholic | 25 October 2000 | [22] | ||

Honorary Doctorates

Peru: Peruvian Academy of Law. (2015)

Peru: Peruvian Academy of Law. (2015) Portugal: University of Coimbra. (2001)

Portugal: University of Coimbra. (2001)

References

- "Falleció el abogado Sánchez Sorondo" [The lawyer Sánchez Sorondo has died]. La Nación (in Spanish). 27 June 2012. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- "Falleció el senador Vaca, del PJ" [Senator Vaca, of the PJ, has died]. La Nación (in Spanish). 21 January 1998. Retrieved 15 February 2016.

- "Habilitan la estación de subte Olleros" [The Olleros subway station is open]. La Nación (in Spanish). 31 May 1997. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "El subte por fin llegó a Juramento" [The subway finally arrived to Juramento]. La Nación (in Spanish). 22 June 1999. Retrieved 17 February 2016.

- "La línea B tiene dos nuevas estaciones" [Line B has two new stations]. La Nación (in Spanish). 10 August 2003. Retrieved 19 February 2016.

- "Primarias presidenciales de la Alianza para el Trabajo, la Justicia y la Educación de 1998", Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre (in Spanish), 2 November 2020, retrieved 8 November 2020

- "El Gobierno decidió la intervención a Corrientes" [The government decided the intervention of Corrientes]. Clarín (in Spanish). 16 December 1999. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- Florencia Carbone (17 December 1999). "Mestre es el interventor designado en Corrientes" [Mestre is the interventor appointed in Corrientes]. La Nación (in Spanish). Retrieved 18 April 2016.

- Convenio militar con los EE.UU. (in Spanish)

- Clifford Kraus (21 December 2001). "Argentine leader, his nation frayed, abruptly resigns". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- Larry Rohter (2 January 2002). "New Argentine President Takes Office". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- "Little sympathy for Argentine president". BBC News. 17 March 2001. Retrieved 7 February 2016.

- "De la Rúa acusó a Tinelli por su caída" [De la Rúa accused Tinelli for his fall]. La Nación (in Spanish). 18 December 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2016.

- Murió Fernando de la Rúa: de la militancia al poder, con una breve y conflictiva gestión (in Spanish)

- "Ceremonia privada en el funeral de De la Rúa". Diario de Cuyo (in Spanish). 11 July 2019. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- Limited, Alamy. "El presidente chileno Ricardo Lagos (L) condecora al presidente argentino Fernando de la Rua en la Casa Rosada, mayo de 18. Lagos está en su primera visita estatal a Argentina desde que se convirtió en presidente en marzo. RR/JP Fotografía de stock". Alamy (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- Limited, Alamy. "El presidente argentino Fernando de la Rua (L) abraza a su homólogo colombiano Andrés Pastrana en la Casa de Gobierno de la Casa Rosada el 12 de octubre de 2000. Pastrana está en una visita oficial de dos días para fortalecer las relaciones bilaterales. ME Fotografía de stock". Alamy (in Spanish). Retrieved 17 November 2020.

- "Order of Merit of the Italian Republic", Wikipedia, 6 November 2020, retrieved 8 November 2020

- Limited, Alamy. "El presidente paraguayo, Luis González Macchi (R), lleva la medalla Argentina San Martín mientras que su homólogo argentino Fernando de la Rua lleva la medalla paraguaya Mariscal Francisco López, durante una ceremonia en el palacio presidencial, mayo de 15. Los líderes se condecoraron entre sí durante una visita estatal de la Rua. RR/TB Fotografía de stock". Alamy (in Spanish). Retrieved 14 October 2020.

- "List of recipients of the Grand Collar of the Order of Prince Henry", Wikipedia, 15 September 2020, retrieved 8 November 2020

- Slovak republic website, State honours : 1st Class in 2001 (click on "Holders of the Order of the 1st Class White Double Cross" to see the holders' table)

- "fernando de la rua en españa - Buscar con Google". www.google.com. Retrieved 8 November 2020.

Bibliography

- Reato, Ceferino (2015). Doce noches [Twelve nights] (in Spanish). Argentina: Sudamericana. ISBN 978-950-07-5203-9.

- Romero, Luis Alberto (2001). Breve historia contemporánea de la Argentina. Argentina: Fondo de cultura económica. ISBN 978-950-557-393-6.

- Smith, Wayne (1983). Juan Peron and the Reshaping of Argentina. United States: University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 0-8229-3464-7.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Jorge Domínguez (as mayor) |

Chief of Government of Buenos Aires 1996–1999 |

Succeeded by Enrique Olivera |

| Preceded by Carlos Menem |

President of Argentina 1999–2001 |

Succeeded by Adolfo Rodríguez Saá |