Fetal circulation

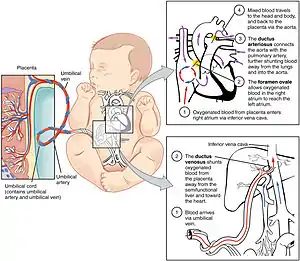

In animals that give live birth, the fetal circulation is the circulatory system of a fetus. The term usually encompasses the entire fetoplacental circulation, which includes the umbilical cord and the blood vessels within the placenta that carry fetal blood.

| Fetal circulation | |

|---|---|

The fetal circulatory system includes three shunts to divert blood from undeveloped and partially functioning organs, as well as blood supply to and from the placenta. | |

| Details | |

| Gives rise to | Circulatory system |

| Anatomical terminology | |

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Development of organ systems |

|---|

| Nervous system |

| Digestive system |

| Reproductive system |

| Urinary system |

| Endocrine system |

| Human development |

| Circulatory system |

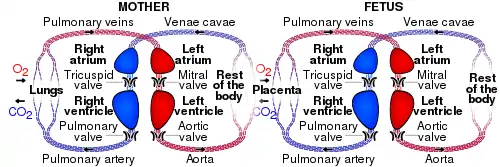

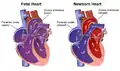

The fetal (prenatal) circulation differs from normal postnatal circulation, mainly because the lungs are not in use. Instead, the fetus obtains oxygen and nutrients from the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord.[1] The advent of breathing and the severance of the umbilical cord prompt various neuroendocrine changes that shortly transform fetal circulation into postnatal circulation.

The fetal circulation of humans has been extensively studied by the health sciences. Much is known also of fetal circulation in other animals, especially livestock and model organisms such as mice, through the health sciences, veterinary science, and life sciences generally.

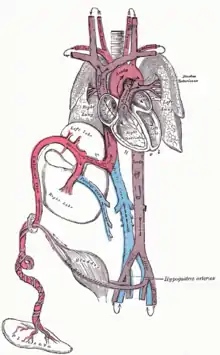

Structure

Blood from the placenta is carried to the fetus by the umbilical vein. In humans, less than a third of this enters the fetal ductus venosus and is carried to the inferior vena cava,[2] while the rest enters the liver proper from the inferior border of the liver. The branch of the umbilical vein that supplies the right lobe of the liver first joins with the portal vein. The blood then moves to the right atrium of the heart. In the fetus, there is an opening between the right and left atrium (the foramen ovale), and most of the blood flows through this hole directly into the left atrium from the right atrium, thus bypassing pulmonary circulation. The continuation of this blood flow is into the left ventricle, and from there it is pumped through the aorta into the body. Some of the blood moves from the aorta through the internal iliac arteries to the umbilical arteries, and re-enters the placenta, where carbon dioxide and other waste products from the fetus are taken up and enter the maternal circulation.[1]

Some of the blood entering the right atrium does not pass directly to the left atrium through the foramen ovale, but enters the right ventricle and is pumped into the pulmonary artery. In the fetus, there is a special connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, called the ductus arteriosus, which directs most of this blood away from the lungs (which are not being used for respiration at this point as the fetus is suspended in amniotic fluid).[1]

Placenta

The circulatory system of the mother is not directly connected to that of the fetus, so the placenta functions as the respiratory center for the fetus as well as a site of filtration for plasma nutrients and wastes. Water, glucose, amino acids, vitamins, and inorganic salts freely diffuse across the placenta along with oxygen. The uterine arteries carry blood to the placenta, and the blood permeates the sponge-like material there. Oxygen then diffuses from the placenta to the chorionic villus, an alveolus-like structure, where it is then carried to the umbilical vein.

Before birth

The circulatory system, consisting of the heart and blood vessels, forms relatively early during embryonic development, and continues to develop in complexity within the growing fetus. A functional circulatory system is a biological necessity, since mammalian tissues can not grow more than a few cell layers thick without an active blood supply. The prenatal circulation of blood is different than the postnatal circulation, mainly because the lungs are not in use. The fetus obtains oxygen and nutrients from the mother through the placenta and the umbilical cord.[1]

Blood from the placenta is carried to the fetus by the umbilical vein. About half of this enters the fetal ductus venosus and is carried to the inferior vena cava, while the other half enters the liver proper from the inferior border of the liver. The branch of the umbilical vein that supplies the right lobe of the liver first joins with the portal vein. The blood then moves to the right atrium of the heart. In the fetus, there is an opening between the right and left atrium (the foramen ovale), and most of the blood flows from the right into the left atrium, thus bypassing pulmonary circulation. The majority of blood flow is into the left ventricle from where it is pumped through the aorta into the body. Some of the blood moves from the aorta through the internal iliac arteries to the umbilical arteries, and re-enters the placenta, where carbon dioxide and other waste products from the fetus are taken up and enter the woman's circulation.[1]

Some of the blood from the right atrium does not enter the left atrium, but enters the right ventricle and is pumped into the pulmonary artery. In the fetus, there is a special connection between the pulmonary artery and the aorta, called the ductus arteriosus, which directs most of this blood away from the lungs (which aren't being used for respiration at this point as the fetus is suspended in amniotic fluid).[1]

After birth

At birth, when the infant breathes for the first time, there is a decrease in the resistance in the pulmonary vasculature, which causes the pressure in the left atrium to increase relative to the pressure in the right atrium. This leads to the closure of the foramen ovale, which is then referred to as the fossa ovalis. Additionally, the increase in the concentration of oxygen in the blood leads to a decrease in prostaglandins, causing closure of the ductus arteriosus. These closures prevent blood from bypassing pulmonary circulation, and therefore allow the neonate's blood to become oxygenated in the newly operational lungs.[3]

Sometimes these postnatal closures are incomplete or absent. The vessels or cross-connections remain open (patent), leading to the following conditions:

- Patent foramen ovale in the heart

- Patent ductus arteriosus in the great vessels

- Patent ductus venosus in the great vessels

Adult remnants

Remnants of the fetal circulation can be found in the adult.[4][5]

| Fetal | Develops |

|---|---|

| foramen ovale | fossa ovalis |

| ductus arteriosus | ligamentum arteriosum |

| extra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein | ligamentum teres hepatis ("round ligament of the liver") |

| intra-hepatic portion of the fetal left umbilical vein (ductus venosus) |

ligamentum venosum |

| proximal portions of the fetal left and right umbilical arteries | umbilical branches of the internal iliac arteries |

| distal portions of the fetal left and right umbilical arteries | umbilical ligaments |

In addition to differences in circulation, the developing fetus also employs a different type of oxygen transport molecule in its hemoglobin from that when it is born and breathing its own oxygen. Fetal hemoglobin enhances the fetus' ability to draw oxygen from the placenta. Its oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve is shifted to the left, meaning that it is able to absorb oxygen at lower concentrations than adult hemoglobin. This enables fetal hemoglobin to absorb oxygen from adult hemoglobin in the placenta, where the oxygen pressure is lower than at the lungs. Until around six months' old, the human infant's hemoglobin molecule is made up of two alpha and two gamma chains (2α2γ). The gamma chains are gradually replaced by beta chains until the molecule becomes hemoglobin A with its two alpha and two beta chains (2α2β).

Physiology

The core concept behind fetal circulation is that fetal hemoglobin (HbF)[6] has a higher affinity for oxygen than does adult hemoglobin, which allows a diffusion of oxygen from the mother's circulatory system to the fetus.

Blood pressure

It is the fetal heart and not the mother's heart that builds up the fetal blood pressure to drive its blood through the fetal circulation.

Intracardiac pressure remains identical between the right and left ventricles of the human fetus.[7]

The blood pressure in the fetal aorta is approximately 30 mmHg at 20 weeks of gestation, and increases to ca 45 mmHg at 40 weeks of gestation.[8] The fetal pulse pressure is ca 20 mmHg at 20 weeks of gestation, increasing to ca 30 mmHg at 40 weeks of gestation.[8]

The blood pressure decreases when passing through the placenta. In the arteria umbilicalis, it is ca 50 mmHg. It falls to 30 mmHg in the capillaries in the villi. Subsequently, the pressure is 20 mm Hg in the umbilical vein, returning to the heart.[9]

Flow

The blood flow through the umbilical cord is approximately 35 mL/min at 20 weeks, and 240 mL/min at 40 weeks of gestation.[10] Adapted to the weight of the fetus, this corresponds to 115 mL/min/kg at 20 weeks and 64 mL/min/kg at 40 weeks.[10] It corresponds to 17% of the combined cardiac output of the fetus at 10 weeks, and 33% at 20 weeks of gestation.[10]

Endothelin and prostanoids cause vasoconstriction in placental arteries, while nitric oxide causes vasodilation.[10] On the other hand, there is no neural vascular regulation, and catecholamines have only little effect.[10]

Prenatal heartbeat

Fetal cardiac activity (also called fetal heartbeat and usually called embryonic cardiac activity before approximately 10 weeks of gestational age) is the rate of contractions during the cardiac cycles of an embryo or fetus. The heart is not fully developed when cardiac activity becomes visible.

In cases of early pregnancy bleeding, the detection of cardiac activity is the main finding that distinguishes a viable pregnancy from a silent miscarriage.

Additional images

Transvaginal ultrasonography of an embryo at 5 weeks and 5 days of gestational age with discernible heartbeat

Transvaginal ultrasonography of an embryo at 5 weeks and 5 days of gestational age with discernible heartbeat Neonatal heart circulation

Neonatal heart circulation

References

- Whitaker, Kent (2001). "Fetal Circulation". Comprehensive Perinatal and Pediatric Respiratory Care. Delmar Thomson Learning. pp. 18–20. ISBN 978-0-7668-1373-1.

- Kiserud, T.; Rasmussen, S.; Skulstad, S. (2000). "Blood flow and the degree of shunting through the ductus venosus in the human fetus". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 182 (1 Pt 1): 147–153. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(00)70504-7. PMID 10649170.

- Le, Tao; Bhushan, Vikas; Vasan, Neil (2010). First Aid for the USMLE Step 1: 2010 20th Anniversary Edition. USA: McGraw-Hill. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-07-163340-6.

- Dudek, Ronald and Fix, James. Board Review Series Embryology (Lippincott 2004). Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- University of Michigan Medical School, Fetal Circulation and Changes at Birth Archived 2007-05-27 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- Edoh D, Antwi-Bosaiko C, Amuzu D (March 2006). "Fetal hemoglobin during infancy and in sickle cell adults". African Health Sciences. 6 (1): 51–54. PMC 1831961. PMID 16615829.

- Johnson P, Maxwell DJ, Tynan MJ, Allan LD (2000). "Intracardiac pressures in the human fetus". Heart. 84 (1): 59–63. doi:10.1136/heart.84.1.59. ISSN 0007-0769. PMC 1729389. PMID 10862590.

- Struijk, P. C.; Mathews, V. J.; Loupas, T.; Stewart, P. A.; Clark, E. B.; Steegers, E. A. P.; Wladimiroff, J. W. (2008). "Blood pressure estimation in the human fetal descending aorta". Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 32 (5): 673–81. doi:10.1002/uog.6137. PMID 18816497.

- "Fetal and maternal blood circulation systems". Swiss Virtual Campus. Retrieved June 29, 2011.

- Kiserud, Torvid; Acharya, Ganesh (2004). "The fetal circulation". Prenatal Diagnosis. 24 (13): 1049–59. doi:10.1002/pd.1062. PMID 15614842.