Firmament

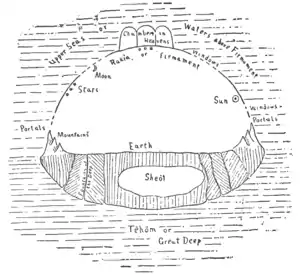

In biblical cosmology, the firmament is the vast solid dome created by God on the second day to divide the primal sea (called tehom) into upper and lower portions so that the dry land could appear.[1][2]

Bible narrative

Genesis 1:6–8

Then God said, “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters, and let it divide the waters from the waters.” Thus God made the firmament, and divided the waters which were under the firmament from the waters which were above the firmament; and it was so. And God called the firmament Heaven. So the evening and the morning were the second day.[3]

Etymology

The word "firmament" is first recorded in a Middle English narrative based on scripture dated 1250.[4] It later appeared in the King James Bible. The word is anglicised from Latin firmamentum, used in the Vulgate (4th century).[5] This in turn is derived from the Latin root firmus, a cognate with "firm".[5] The word is a Latinization of the Greek stereōma, which appears in the Septuagint (c. 200 BCE).

History

The word firmament translates shamayim (שָׁמַיִם) or rāqîa (רָקִ֫יעַ), a word used in Biblical Hebrew. shamayim is translated as "heaven". Rāqîa derives from the root raqqəʿ (רָקַע), meaning "to beat or spread out thinly", e.g., the process of making a dish by hammering thin a lump of metal.[5][6]

The Hebrews believed the sky was a solid dome with the Sun, Moon, planets and stars embedded in it.[7] According to The Jewish Encyclopedia:

The Hebrews regarded the earth as a plain or a hill figured like a hemisphere, swimming on water. Over this is arched the solid vault of heaven. To this vault are fastened the lights, the stars. So slight is this elevation that birds may rise to it and fly along its expanse.[8]

The 6th-century Egyptian traveller Cosmas Indicopleustes formulated a detailed Christian view of the universe, based on various Biblical texts and on earlier theories by Theophilus of Antioch (2nd century CE) and by Clement of Alexandria (c. 150 – c. 215). Cosmas described a flat rectangular world surrounded by four seas; at the far edges of the seas, four immense vertical walls supported a vaulted roof, the firmament, above which in a further vaulted space lived angels who moved the heavenly bodies and controlled rainfall from a vast cistern.[9] Augustine (354-430) considered that too much learning had been expended on the nature of the firmament.[10] "We may understand this name as given to indicate not it is motionless but that it is solid", he wrote.[10] Saint Basil (330-379) argued for a fluid firmament.[10] According to Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) the firmament had a "solid nature" and stood above a "region of fire, wherein all vapor must be consumed".[11]

The Copernican Revolution of the 16th century led to reconsideration of these matters. In 1554 John Calvin proposed interpreting the "firmament" as clouds.[12] "He who would learn astronomy and other recondite arts, let him go elsewhere", wrote Calvin.[12] "As it became a theologian, [Moses] had to respect us rather than the stars", Calvin wrote. Such a doctrine of accommodation allowed Christians to accept the findings of science without rejecting the authority of scripture.[12][13]

Scientific development

The Greeks and Stoics adopted a model of celestial spheres after the discovery of the spherical Earth in the 4th to 3rd centuries BCE. The Medieval Scholastics adopted a cosmology that fused the ideas of the Greek philosophers Aristotle and Ptolemy.[14] This cosmology involved celestial orbs, nested concentrically inside one another, with the earth at the center. The outermost orb contained the stars and the term firmament was then transferred to this orb. There were seven inner orbs for the seven wanderers of the sky, and their ordering is preserved in the naming of the days of the week.

Even Copernicus' heliocentric model included an outer sphere that held the stars (and by having the earth rotate daily on its axis it allowed the firmament to be completely stationary). Tycho Brahe's studies of the nova of 1572 and the Comet of 1577 were the first major challenges to the idea that orbs existed as solid, incorruptible, material objects.[15]

In 1584, Giordano Bruno proposed a cosmology without a firmament: an infinite universe in which the stars are actually suns with their own planetary systems.[16] After Galileo began using a telescope to examine the sky, it became harder to argue that the heavens were perfect, as Aristotelian philosophy required. By 1630, the concept of solid orbs was no longer dominant.[17]

See also

Citations

- Pennington 2007, p. 42.

- Ringgren 1990, p. 92.

- Genesis 1:6–8

- "firmament", Oxford English Dictionary (1989). "ðo god bad ben ðe firmament". From The story of Genesis and Exodus Archived 2021-02-01 at the Wayback Machine (1250).

- "Online Etymology Dictionary – Firmament". Archived from the original on 2012-10-18. Retrieved 2010-10-25.

- "Lexicon Results Strong's H7549 – raqiya'". Blue Letter Bible. Blue Letter Bible. Archived from the original on 2011-11-03. Retrieved 2009-12-04.

- Seely, Paul H. (1991). "The Firmament and the Water Above" (PDF). Westminster Theological Journal. 53: 227–40. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-03-05. Retrieved 2010-02-02.

- "Cosmogony". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- White, Andrew Dickson (1896). A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom: Volume 1. New York: D. Appleton and Company. pp. 91–92.

- Grant, Edward, Planets, stars, and orbs: the medieval cosmos, 1200–1687. p. 335.

- Saint Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologica, "Whether there are waters above the firmament? Archived 2011-05-25 at the Wayback Machine"

- Luigi Piccardi, W. Bruce Masse, Myth and geology, p. 40

- Firmament Archived 2010-11-26 at the Wayback Machine, Catholic Encyclopedia - "On this point as on many others, the Bible simply reflects the current cosmological ideas and language of the time."

- Grant, p. 308.

- Grant, p. 348.

- Giordano Bruno, De l'infinito universo e mondi (On the Infinite Universe and Worlds), 1584.

- Grant, p. 349.

Bibliography

- Pennington, Jonathan T. (2007). Heaven and earth in the Gospel of Matthew. Brill. ISBN 978-9004162051. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Ringgren, Helmer (1990). "Yam". In Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer (eds.). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Eerdmans. ISBN 9780802823304. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Andrews, Tamra (2000). Dictionary of Nature Myths: Legends of the Earth, Sea, and Sky. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195136777. Archived from the original on 2020-11-06. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Bandstra, Barry L. (1999). Reading the Old Testament: An Introduction to the Hebrew Bible. Wadsworth. ISBN 0495391050. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Berlin, Adele (2011). "Cosmology and creation". In Berlin, Adele; Grossman, Maxine (eds.). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199730049. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Blenkinsopp, Joseph (2011). Creation, Un-Creation, Re-Creation: A Discursive Commentary on Genesis 1–11. T&T Clarke International. ISBN 9780567574558. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Broadie, Sarah (1999). "Rational Theology". In Long, A.A. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521446679. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Bunnin, Nicholas; Yu, Jiyuan (2008). The Blackwell Dictionary of Western Philosophy. Blackwells. ISBN 9780470997215. Archived from the original on 2020-10-14. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Clifford, Richard J (2017). "Creatio ex Nihilo in the Old Testament/Hebrew Bible". In Anderson, Gary A.; Bockmuehl, Markus (eds.). Creation ex nihilo: Origins, Development, Contemporary Challenges. University of Notre Dame. ISBN 9780268102562. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Couprie, Dirk L. (2011). Heaven and Earth in Ancient Greek Cosmology: From Thales to Heraclides Ponticus. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 9781441981165. Archived from the original on 2020-11-02. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Grunbaum, Adolf (2013). "Science and the Improbability of God". In Meister, Chad V.; Copan, Paul (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Philosophy of Religion. Routledge. ISBN 9780415782944. Archived from the original on 2020-07-26. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- James, E.O. (1969). Creation and Cosmology: A Historical and Comparative Inquiry. Brill. ISBN 9789004378070. Archived from the original on 2020-10-30. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- López-Ruiz, Carolina (2010). When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674049468. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Mabie, F.J (2008). "Chaos and Death". In Longman, Tremper; Enns, Peter (eds.). Dictionary of the Old Testament. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830817832. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- May, Gerhard (2004). Creatio ex nihilo. T&T Clarke International. ISBN 9780567456229. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Nebe, Gottfried (2002). "Creation in Paul's Theology". In Hoffman, Yair; Reventlow, Henning Graf (eds.). Creation in Jewish and Christian Tradition. Sheffield Academic Press. ISBN 9781841271620. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Muller, Richard A. (2017). Dictionary of Latin and Greek Theological Terms. Baker Academic. ISBN 9781493412082. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Pruss, Alexander (2007). "Ex Nihilo Nihil Fit". In Campbell, Joseph Keim; O'Rourke, Michael; Silverstein, Harry (eds.). Causation and Explanation. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262033633. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Rubio, Gonzalez (2013). "Time Before Time: Primeval Narratives in Early Mesopotamian Literature". In Feliu, L.; Llop, J. (eds.). Time and History in the Ancient Near East: Proceedings of the 56th Recontre Assyriologique Internationale at Barcelona, 26–30 July 2010. Eisenbrauns. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Waltke, Bruce K. (2011). An Old Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN 9780310863328. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Walton, John H. (2006). Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament: Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible. Baker Academic. ISBN 0-8010-2750-0. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Walton, John H. (2015). The Lost World of Adam and Eve: Genesis 2-3 and the Human Origins Debate. InterVarsity Press. ISBN 9780830897711. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Wasilewska, Ewa (2000). Creation Stories of the Middle East. Jessica Kingsley Publishers. ISBN 9781853026812. Archived from the original on 2020-11-03. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Wolfson, Harry Austryn (1976). The Philosophy of the Kalam. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674665804. Archived from the original on 2016-05-07. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

- Wolters, Albert M. (1994). "Creatio ex nihilo in Philo". In Helleman, Wendy (ed.). Hellenization Revisited: Shaping a Christian Response Within the Greco-Roman World. University Press of America. ISBN 9780819195449. Archived from the original on 2021-02-01. Retrieved 2021-02-01.

External links

| Look up firmament in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Firmament. |

- The Vault of Heaven.

- Denver Radio / YouTube Debate on the Firmament between well-known creationist and atheist opponents.