Floating Battery of Charleston Harbor

The Floating Battery of Charleston Harbor was an ironclad vessel that was constructed by the Confederacy in early 1861, a few months before the American Civil War ignited. Apart from being a marvel to contemporary Charlestonians, it was a strategic naval artillery platform that took part in the bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12 and April 13, 1861, making it the first floating battery to engage in hostilities during the Civil War.[1]

Background

Following the November 6, 1860, election of Abraham Lincoln, there was a popular outcry for secession in Charleston, South Carolina. Relations between the local citizens and the U.S. Army forces that occupied various posts around the Charleston harbor area began to deteriorate. On November 8, Colonel John L. Gardner, federal garrison commander, angered Charlestonians when he attempted to remove all of the small-arms ammunition from the Charleston Arsenal.[2] Gardner attempted to pacify the angry crowd by returning the ammunition which may have saved him at the time but he would eventually be relieved of his command for his actions nonetheless. Governor F. W. Pickens ordered South Carolina State troops to stand guard over the arsenal. When the new garrison commander, Major Robert Anderson, sent Captain J. G. Foster to get 100 muskets for the workmen of Castle Pinckney and Fort Sumter, he was flatly refused by Colonel B. H. Huger who cited that special orders from Washington would be necessary.[3]

Maj. Anderson consolidated the majority of his troops at Fort Moultrie but found this to be a poorly defensible position. Sand dunes rose almost to the height of the parapet walls on the inland side and neighboring houses towered above the fort walls affording too many opportunities for militia sharpshooters.[4] Following the December 20 secession of South Carolina from the Union, Anderson planned an evacuation across the harbor channel to Ft. Sumter. State troops sounded alarms on the morning of December 27 when they discovered that Anderson's forces had abandoned Ft. Moultrie during the evening of December 26, spiking the guns and setting fire to the gun carriages before the last troops left. This infuriated the citizens of Charleston who viewed the evacuation and destruction as a breach of good faith.[5] Governor Pickens ordered that all remaining federal positions except Ft. Sumter were to be seized. State troops quickly occupied Ft. Moultrie (capturing 56 guns), Ft. Johnson, and the Morris Island Battery. At about 4 p.m. on December 27, an assault force of 150 men seized the Union-occupied Castle Pinckney fortification capturing 24 guns and mortars without bloodshed. On December 30, the federal arsenal was captured with the Union crew held in their quarters. The capture from the arsenal was massive with more than 22,000 ordnance pieces being appropriated by the militia.[6]

The Confederates promptly made repairs, unspiked the guns, built new gun carriages, and reinforced the fortifications at Ft. Moultrie. Dozens of new batteries and defense positions were constructed throughout the Charleston harbor area and armed with weapons captured from the arsenal. Intent on gaining a strategic advantage in artillery position, the Confederates adopted the contemporary military idea of implementing floating batteries. The French Navy had enjoyed success using floating batteries in the Battle of Kinburn (1855) to demolish Russian forts during the Crimean War.[7]

Construction

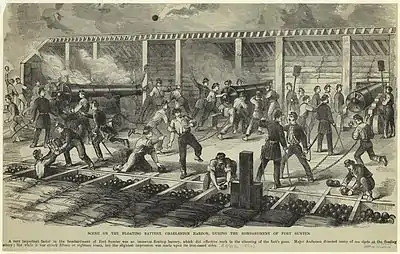

The battery was constructed on the waterfront of Charleston, South Carolina in view of the Union forces at Ft. Sumter near the mouth of Charleston harbor. Construction began in January 1861, under the leadership of Lieutenant John R. Hamilton formerly an officer in the United States Navy and the son of a former governor of South Carolina.[8] Built of pine heartwood logs sawn twelve inches (305 mm) square, it was buttressed by palmetto logs on the bow and the exterior of the vessel was clad in two layers of railroad iron vertically and four layers of boiler iron horizontally.[9] Its dimensions were approximately twenty-five feet wide by one hundred feet long. The massive front bow of the battery resembled a peaked barn to onlookers who branded it with that nickname. Along the barn face were four evenly-spaced casemate windows suitable for the naval guns to fire through. The battery's armament consisted of two 42 lb and two 32 lb naval artillery guns.[9] A detailed drawing by a Confederate officer illustrates the guns (the fourth is not depicted).[10] To offset the weight of the barn with the armament added, the vessel was counterbalanced at the rear with 6 ft. thick sandbag emplacements along the length of the stern. The powder magazines were below the sandbags while shot was stored behind the guns in covered bins beneath the deck. Positioned behind the stern and on its own separate raft was a small floating hospital.[9]

The March 30, 1861, issue of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper contains a detailed sketch of the hospital interior. There appears to be at least eight hospital beds and two operating tables. Access was gained by a steeply-angled staircase through a hatch in the roof. A framed wooden door allowed for entry and exit on the starboard side of the hospital closer to the waterline while two framed glass sash windows allowed in light on the port side. Window casements framed into the roof allowed for some additional light and ventilation.[11]

Reaction

Captain John G. Foster, a Union Army engineering officer observing from Fort Sumter, wrote reports to his superiors about the progress of the battery construction. Foster's assessment of the battery was dismissive, "...I think it can be destroyed by our fire before it has time to do much damage..." and he followed a few days later with, "...I do not think this floating battery will prove very formidable..." Nonetheless, his superior, Major Robert Anderson was apprehensive enough that he inquired for specific instructions from Washington regarding the threat of the battery. He was instructed that if he became convinced that the battery was advanced for the purpose of immediate attack then he would be justified in firing on it but if it was only being moved for the purposes of general emplacement that he should exercise forbearance.[12]

Members of the Confederate crew were apprehensive about the battery as well but for different reasons. Some of them feared that it would capsize and began referring to it as "the slaughter pen". Union soldiers glibly named it "the raft". Crowds gathered on the waterfront of Charleston to marvel at and celebrate the completed battery in ceremony on March 15 despite cold weather. A seven gun salute was fired to honor the seven states that had already seceded and after a pause, an additional gun was fired on behalf of Arkansas whose secession was pending.[13] Public reaction in the North to the floating battery was as marked as had been their Southern counterparts' enthusiasm. The New York Herald invited readers to visit their offices so they could see a palmetto log similar to those used in the battery. The Herald also posted that another log had been brought north to sell to showman P.T. Barnum but that Barnum had balked at the $150 asking price.[12]

Bombardment of Fort Sumter

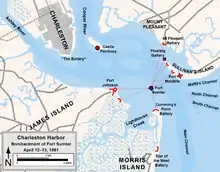

The enemy next opened on Fort Moultrie, between which and Fort Sumter a steady and almost constant fire was kept up throughout the day. These three points—Fort Moultrie, Cummings Point, and the end of Sullivan's Island, where the floating battery, Dahlgren battery, and the enfilade battery were placed—were the points to which the enemy seemed almost to confine his attention, although he fired a number of shots at Captain Butler's mortar battery, situated to the east of Fort Moultrie, and a few at Captain James' mortar batteries at Fort Johnson.

During the day (12th) the fire of my batteries was kept up most spiritedly, the guns and mortars being worked in the coolest manner, preserving the prescribed intervals of firing. Towards evening it became evident that our fire was very effective, as the enemy was driven from his barbette gun which he attempted to work in the morning, and his fire was confined to his casemated guns, but in a less active manner than in the morning, and it was observed that several of his guns en barbette were disabled. During the whole of Friday night our mortar batteries continued to throw shells, but, in obedience to orders, at longer intervals. The night was rainy and dark, and as it was almost confidently expected that the United States fleet would attempt to laud troops Upon the islands or to throw men into Fort Sumter by means of boats, the greatest vigilance was observed at all our channel batteries, and by our troops on both Morris and Sullivan's Islands.

Brig. Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard, April 27, 1861[14]

Sometime in the dark hours between April 9 and April 10,[15] the battery was towed and emplaced near the western end of Sullivan's Island by order of Brigadier General P. G. T. Beauregard. It was manned by members of Company D of the South Carolina Artillery Battalion and commanded by Capt. Hamilton. On April 12, Hamilton's floating battery commenced in a 34-hour intermittent artillery siege against Union army forces occupying Ft. Sumter.[16]

The battery was struck several times by artillery fire from Ft. Sumter.[8] According to Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia, "... The guns that bore on the three batteries at the west end of 'Sullivan's Island' were 10 32-pounders, situated on the left face, and on at the pan-coupe of the salient angle, (four embrasures being bricked up.)"[17] By midday, a shortage of cartridges in Ft. Sumter forced the Union troops to lower the number of guns to only two in active battery against the batteries at the western end of Sullivan's Island.[17] "The so-called 'floating battery' was struck very frequently by shot, one of them penetrating at the angle between the front and the roof, entirely through the iron covering and wood work beneath, and wounding one man. The rest of the 32-pounder balls failed to penetrate the front or the roof, but were deflected from their surfaces, which were arranged at a suitable angle for this purpose."[17] The damage was considered minimal and with Maj. Anderson's surrender of Ft. Sumter, the Confederates and the crew of Hamilton's floating battery were victorious. Newspapers and magazines proliferated details of the battle and surrender. "On Friday, 12th, at 27 minutes past 4 A. M., General Beauregard, in accordance with instructions received on Wednesday from the Secretary of War of the Southern Confederacy, opened fire upon Fort Sumter. Forts Johnson and Moultrie, the iron battery at Cumming's Point, and the Stevens Floating Battery, kept up an active cannonade during the entire day, and probably during the past night. The damage done to Fort Sumter is stated by the Confederate authorities to have been considerable. Guns had been dismounted, and a part of the parapet swept away."[18] - Harper's Weekly

Beauregard commended Capt. Hamilton in his battle report written at the Provisional Army Headquarters, Charleston, S.C., April 27, 1861. He wrote "...I would also mention in the highest terms of praise Captains Calhoun and Hallonquist, assistant commandants of batteries to Colonel Ripley; and the following commanders of batteries on Sullivan's Island: Capt. J. R. Hamilton, commanding the floating battery and Dahlgren gun; Captains Butler, South Carolina Army, and Bruns, aide-de-camp to General Dunovant, and Lieutenants Wagner, Rhett, Yates, Valentine, and Parker."[14]

Fate

Damage was assessed with reports and twenty-two photographs "showing the condition of Forts Sumter and Moultrie and of the floating battery after the surrender of the former fort" and sent to LeRoy Pope Walker, Secretary of War for the Confederate States of America, in Montgomery, Alabama on April 27, 1861.[19] Details of the battery's history beyond this point are somewhat elusive. According to a United States Coast Survey chart of 1863, the battery is depicted as anchored in the harbor between Middle Ground and Ft. Johnson but later charts rendered in 1865 do not indicate the existence of the battery. The Confederates apparently ended up stripping the iron off the battery at some point to construct a navigable ironclad.[20] There may be evidence that the dismantled battery broke up later during a storm as early as the latter part of 1863. One diarist, serving on Morris Island, wrote that they had a shortage of fuel until one morning after a storm when they found logs purportedly from the battery washed up on the beach. In 1865, a visitor to Charleston described the harbor entrance with this description, "... Just beyond the ruin (of Ft. Sumter) at the left, lies the wreck of the famous old floating battery ... A portion of one of its sides, with four portholes visible, still remains above the water. ..."[12]

Notes

- Suhr

- Swanberg, pp. 19-20.

- Swanberg, p. 44.

- Swanberg, p. 38.

- Hanson, 2003.

- Ripley, p. 6.

- Wilson, p. xxxiv.

- Suhr, p. 1.

- Bostick, p. 57.

- Appleton's Annual Cyclopædia incorrectly lists the armament as 4 42-pounders, p. 666.

- Interior, p. 292.

- Ripley, p. 10.

- FROM 1861.

- BRIGADIER 1861.

- LATEST 1861.

- Ripley, p. 9.

- Appletons, p. 667.

- Beginning

- Beauregard, 1861.

- Suhr 1996c.

References

- Appletons' Annual Cyclopædia and Register of Important Events of the Year... 1867. (1867). pp 666–667. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Beauregard, P. G. T. (1861). "Reports of Brig. Gen. G. T. Beauregard, C. S. Army, of Operations against Fort Sumter. OPERATIONS IN CHARLESTON HARBOR, S.C." Official Records of the American Civil War. Series I, Volume 1, (S#1) Chapter I. from Civilwarhome.com Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- "Beginning of the War", 1861-04-20. Harper's Weekly, p. 247 Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Brigadier General Beauregard's Battle Report. (1861-04-27). Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Bostick, Douglas W. (2004-04). Secession to Siege 1860/1865 - The Charleston Engravings, JogglingBoard Press. ISBN 0-9753498-0-5 Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- "FROM CHARLESTON; The Floating-Battery Finished A Snowstorm Inviting Vessels to be Wrecked The Hibernian Ball Northern Men in the Southern Service, &c." The New York Times, (1861-03-20). Retrieved on 2008-06-29.

- "Interior of the hospital attached to the floating battery in Charleston Harbor, S.C. from a sketch by our special artist now in Charleston", 1861-03-30. Illustration in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, v. 11, no. 279 (1861 March 30), p. 292. Retrieved 2008-07-08.

- Hanson, David C. (2003) The Civil War and Reconstruction The Fort Sumter Crisis. Virginia Western Community College. Retrieved 2008-07-25

- "LATEST FROM CHARLESTON; THE FLOATING BATTERY PLACED IN POSITION." The New York Times, (1861-04-11). Retrieved on 2008-06-29.

- Ripley, Warren (1992). "South Builds Floating Battery". In Wilcox, Arthur M. & Ripley, Warren, The Civil War at Charleston, pp. 9–10. Sixteenth Ed. Evening-Post Publishing Co.

- Ripley, Warren (1992). "Arsenal Falls In Bloodless Coup". In Wilcox, Arthur M. & Ripley, Warren, The Civil War at Charleston, p. 6. Sixteenth Ed. Evening-Post Publishing Co.

- Suhr, Robert Collins. (1996-07)."Military Technology: The Confederate Floating Battery Revival During the American Civil War". America's Civil War, Weider History Group. Retrieved on 2008-06-29.

- Swanberg, W.A. (1957). First Blood:The Story of Fort Sumter, Charles Scribner's Sons Publishing, New York. pp. 373

- The Confederate War Journal. Volume 1, No. 2, May 1893. War Journal Publishing. p. 13.

- Wilcox, Arthur M. (1992). Southern Fortifications bearing on Fort Sumter April 12–13, 1861.. In Wilcox, Arthur M. & Ripley, Warren, The Civil War at Charleston, p. 14. Sixteenth Ed. Evening-Post Publishing Co.

- Wilson, Herbert Wrigley. (1896). Ironclads in action: a sketch of naval warfare from 1855 to 1895, with some account of the development of the battleship in England, Volume 1. Little & Brown. p. xxxiv.

- Wright, Louise W. (1905). Louise Wigfall Wright, 1846-1915 A Southern Girl in '61: The War-Time Memories of a Confederate Senator's Daughter. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1905. Illustration of CAPT. JOHN RANDOLPH HAMILTON Commander of the Floating Battery, C. S. N. & MRS. JOHN RANDOLPH HAMILTON. Retrieved 2008-07-08.