Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also called the Northern Army, referred to the United States Army, the land force that fought to preserve the Union of the collective states. Also known as the Federal Army, it proved essential to the preservation of the United States as a working, viable republic.

The Union Army was made up of the permanent regular army of the United States, but further fortified, augmented, and strengthened by the many temporary units of dedicated volunteers as well as including those who were drafted in to service as conscripts. To this end, the Union Army fought and ultimately triumphed over the efforts of the Confederate States Army in the American Civil War.

Over the course of the war, 2,128,948 men enlisted in the Union Army,[1] including 178,895 colored troops; 25% of the white men who served were foreign-born.[2] Of these soldiers, 596,670 were killed, wounded or went missing.[3] The initial call-up was for just three months, after which many of these men chose to reenlist for an additional three years.

Formation

When the American Civil War began in April 1861, the U.S. Army consisted of ten regiments of infantry, four of artillery, two of cavalry, two of dragoons, and three of mounted infantry. The regiments were scattered widely. Of the 197 companies in the army, 179 occupied 79 isolated posts in the West, and the remaining 18 manned garrisons east of the Mississippi River, mostly along the Canada–United States border and on the Atlantic coast. There were only 16,367 men in the U.S. Army, including 1,108 commissioned officers. Approximately 20% of these officers — most of them Southerners — resigned, choosing to tie their lives and fortunes to the Army of the Confederacy.[4]

In addition, almost 200 West Point graduates who had previously left the Army, including Ulysses S. Grant, William Tecumseh Sherman, and Braxton Bragg, returned to service at the outbreak of the war. This group's loyalties were far more evenly divided, with 92 donning Confederate gray and 102 putting on the blue of the United States Army.

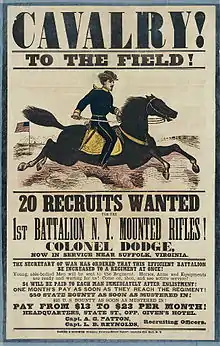

With the Southern slave states declaring secession from the United States, and with this drastic shortage of men in the army, President Abraham Lincoln called on the states to raise a force of 75,000 men for three months to put down this subversive insurrection. Lincoln's call forced the border states to choose sides, and four seceded, making the Confederacy eleven states strong. It turned out that the war itself proved to be much longer and far more extensive in scope and scale than anyone on either side, Union North or Confederate South, expected or even imagined at the outset on the date of July 22, 1861. That was the day that Congress initially approved and authorized subsidy to allow and support a volunteer army of up to 500,000 men to the cause.

The call for volunteers initially was easily met by patriotic Northerners, abolitionists, and even immigrants who enlisted for a steady income and meals. Over 10,000 German Americans in New York and Pennsylvania immediately responded to Lincoln's call, along with Northern French Americans, who also were quick to volunteer. As more men were needed, however, the number of volunteers fell and both money bounties and forced conscription had to be turned to. Many Southern Unionists would also fight for the Union Army. An estimated 100,000 white soldiers from states within the Confederacy served in Union Army units.[5] Between April 1861 and April 1865, at least 2,128,948 men served in the United States Army, of whom the majority were volunteers.

It is a misconception that the South held an advantage because of the large percentage of professional officers who resigned to join the Confederate army. At the start of the war, there were 824 graduates of the U.S. Military Academy on the active list; of these, 296 resigned or were dismissed, and 184 of those became Confederate officers. Of the approximately 900 West Point graduates who were then civilians, 400 returned to the United States Army and 99 to the Confederate. Therefore, the ratio of U.S. Army to Confederate professional officers was 642 to 283.[6] (One of the resigning officers was Robert E. Lee, who had initially been offered the assignment as commander of a field army to suppress the rebellion. Lee disapproved of secession, but refused to bear arms against his native state, Virginia, and resigned to accept the position as commander of Virginian C.S. forces. He eventually became the commander of the Confederate army.) The South did have the advantage of other military colleges, such as The Citadel and Virginia Military Institute, but they produced fewer officers. Though officers were able to resign, enlisted soldiers did not have this right. As they usually had to either desert or wait until their enlistment term was over in order to join the Confederate States Army; their total number is unknown.

Major organizations

The Union Army was composed of numerous organizations, which were generally organized geographically.

- Military division

- A collection of Departments reporting to one commander (e.g., Military Division of the Mississippi, Middle Military Division, Military Division of the James). Military Divisions were similar to the more modern term Theater; and were modeled close to, though not synonymous with, the existing theaters of war.

- Department

- An organization that covered a defined region, including responsibilities for the Federal installations therein and for the field armies within their borders. Those named for states usually referred to Southern states that had been occupied. It was more common to name departments for rivers (such as Department of the Tennessee, Department of the Cumberland) or regions (Department of the Pacific, Department of New England, Department of the East, Department of the West, Middle Department).

- District

- A territorial subdivision of a Department (e.g., District of Cairo, District of East Tennessee). There were also Subdistricts for smaller regions.

- Army

- The fighting force that was usually, but not always, assigned to a District or Department but could operate over wider areas. Some of the most prominent armies were:

- Army of the Cumberland, the army operating primarily in Tennessee, and later Georgia, commanded by William S. Rosecrans and George Henry Thomas.

- Army of Georgia, operated in the March to the Sea and the Carolinas commanded by Henry W. Slocum.

- Army of the Gulf, the army operating in the region bordering the Gulf of Mexico, commanded by Benjamin Butler, Nathaniel P. Banks, and Edward Canby.

- Army of the James, the army operating on the Virginia Peninsula, 1864–65, commanded by Benjamin Butler and Edward Ord.

- Army of the Mississippi, a briefly existing army operating on the Mississippi River, in two incarnations—under John Pope and William S. Rosecrans in 1862; under John A. McClernand in 1863.

- Army of the Ohio, the army operating primarily in Kentucky and later Tennessee and Georgia, commanded by Don Carlos Buell, Ambrose E. Burnside, John G. Foster, and John M. Schofield.

- Army of the Potomac, the principal army in the Eastern Theater, commanded by George B. McClellan, Ambrose E. Burnside, Joseph Hooker, and George G. Meade.

- Army of the Shenandoah, the army operating in the Shenandoah Valley, under David Hunter, Philip Sheridan, and Horatio G. Wright.

- Army of the Tennessee, the most famous army in the Western Theater, operating through Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi, Georgia, and the Carolinas; commanded by Ulysses S. Grant, William T. Sherman, James B. McPherson, and Oliver O. Howard.

- Army of Virginia, the army assembled under John Pope for the Northern Virginia Campaign.

Each of these armies was usually commanded by a major general. Typically, the Department or District commander also had field command of the army of the same name, but some conflicts within the ranks occurred when this was not true, particularly when an army crossed a geographic boundary.

The regular army, the permanent United States Army, was intermixed into various formations of the Union Army, forming a cadre of experienced and skilled troops. They were regarded by many as elite troops and often held in reserve during battles in case of emergencies. This force was quite small compared to the massive state-raised volunteer forces that comprised the bulk of the Union Army.

Personnel organization

Rough unit sizes for Union combat units during the war:[7]

- Corps – 12,000 to 14,000

- Division – 3,000 to 7,000

- Brigade – 800 to 1,700

- Regiment – 350 to 400

- Company – 34 to 40

Soldiers were organized by military specialty. The combat arms included infantry, cavalry, artillery, and other such smaller organizations such as the United States Marine Corps, which, at some times, was detached from its navy counterpart for land based operations. The Signal Corps was created and deployed for the first time, through the leadership of Albert J. Myer.

Below major units like armies, soldiers were organized mainly into regiments, the main fighting unit with which a soldier would march and be deployed, commanded by a colonel, lieutenant colonel, or possibly a major. According to William J. Hardee's "Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics" (1855), the primary tactics for riflemen and light infantry in use immediately prior and during the war, there would typically be, in each regiment, ten companies, each commanded by a captain, and deployed according to the ranks of captains. Some units only had between four and eight companies and were generally known as battalions.[8] Regiments were almost always raised within a single state, and were generally referred by number and state, e.g. 54th Massachusetts, 20th Maine, etc.

Regiments were usually grouped into brigades under the command of a brigadier general. However, brigades were changed easily as the situation demanded; under the regimental system the regiment was the main permanent grouping. Brigades were usually formed once regiments reached the battlefield, according to where the regiment might be deployed, and alongside which other regiments.

Leaders

Several men served as generals-in-chief of the Union Army throughout its existence:

- Winfield Scott: July 5, 1841 – November 1, 1861

- George B. McClellan: November 1, 1861 – March 11, 1862

- Henry W. Halleck: July 23, 1862 – March 9, 1864

- Ulysses S. Grant: March 9, 1864 – March 4, 1869

The gap from March 11 to July 23, 1862, was filled with direct control of the army by President Lincoln and United States Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, with the help of an unofficial "War Board" that was established on March 17, 1862. The board consisted of Ethan A. Hitchcock, the chairman, with Department of War bureau chiefs Lorenzo Thomas, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph G. Totten, James W. Ripley, and Joseph P. Taylor.[9]

Scott was an elderly veteran of the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War and could not perform his duties effectively. His successor, Maj. Gen. McClellan, built and trained the massive Union Army of the Potomac, the primary fighting force in the Eastern Theater. Although he was popular among the soldiers, McClellan was relieved from his position as general-in-chief because of his overcautious strategy and his contentious relationship with his commander-in-chief, President Lincoln. (He remained commander of the Army of the Potomac through the Peninsula Campaign and the Battle of Antietam.) His replacement, Major General Henry W. Halleck, had a successful record in the Western Theater, but was more of an administrator than a strategic planner and commander.

Ulysses S. Grant was the final commander of the Union Army. He was famous for his victories in the West when he was appointed lieutenant general and general-in-chief of the Union Army in March 1864. Grant supervised the Army of the Potomac (which was formally led by his subordinate, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade) in delivering the final blows to the Confederacy by engaging Confederate forces in many fierce battles in Virginia, the Overland Campaign, conducting a war of attrition that the larger Union Army was able to survive better than its opponent. Grant laid siege to Lee's army at Petersburg, Virginia, and eventually captured Richmond, the capital of the Confederacy. He developed the strategy of coordinated simultaneous thrusts against wide portions of the Confederacy, most importantly the Georgia and Carolinas Campaigns of William Tecumseh Sherman and the Shenandoah Valley campaign of Philip Sheridan. These campaigns were characterized by another strategic notion of Grant's-better known as total war—denying the enemy access to resources needed to continue the war by widespread destruction of its factories and farms along the paths of the invading Union armies.

Grant had critics who complained about the high numbers of casualties that the Union Army suffered while he was in charge, but Lincoln would not replace Grant, because, in Lincoln's words: "I cannot spare this man. He fights."

Among memorable field leaders of the army were Nathaniel Lyon (first Union general to be killed in battle during the war), William Rosecrans, George Henry Thomas and William Tecumseh Sherman. Others, of lesser competence, included Benjamin F. Butler.

Union victory

The decisive victories by Grant and Sherman resulted in the surrender of the major Confederate armies. The first and most significant was on April 9, 1865, when Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia to Grant at Appomattox Court House. Although there were other Confederate armies that surrendered in the following weeks, such as Joseph E. Johnston's in North Carolina, this date was nevertheless symbolic of the end of the bloodiest war in American history, the end of the Confederate States of America, and the beginning of the slow process of Reconstruction.

Motivations

Anti-slavery sentiment

In his 1997 book examining the motivations of the American Civil War's soldiers, For Cause and Comrades, historian James M. McPherson states that Union soldiers fought to preserve the United States, as well as to end slavery, stating that:

While restoration of the Union was the main goal for which they fought, they became convinced that this goal was unattainable without striking against slavery.

— James M. McPherson, For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War, (1997), p. 118, emphasis added.[10]

McPherson states that witnessing the slave system of the Confederacy first-hand also strengthened the anti-slavery views of Union soldiers,[10] who were appalled by its brutality.[10] He stated that "Experience in the South reinforced the antislavery sentiments of many soldiers."[10] One Pennsylvanian Union soldier spoke to a slave woman whose husband was whipped, and was appalled by what she had to tell him of slavery. He stated that "I thought I had hated slavery as much as possible before I came here, but here, where I can see some of its workings, I am more than ever convinced of the cruelty and inhumanity of the system."[10]

Ethnic composition

The Union Army was composed of many different ethnic groups, including large numbers of immigrants. About 25% of the white men who served in the Union Army were foreign-born.[2] This means that about 1,600,000 enlistments were made by men who were born in the United States, including about 200,000 African Americans. About 200,000 enlistments were by men born in one of the German states (although this is somewhat speculative since anyone serving from a German family tended to be identified as German regardless of where they were actually born).[11] About 200,000 soldiers and sailors were born in Ireland. Although some soldiers came from as far away as Malta, Italy, India, and Russia, most of the remaining foreign-born soldiers came from Great Britain and Canada.

| Number | Percent | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| 1,000,000 | 45.4 | Native-born white Americans. |

| 216,000 | 9.7 | German-born |

| 210,000 | 9.5 | African-American. Half were freedmen who lived in the North, and half were ex-slaves from the South. They served under mainly white officers in more than 160 "colored" regiments and in Federal U.S. regiments organized as the United States Colored Troops (USCT).[13][14][15][16] |

| 200,000 | 9.1 | Irish-born |

| 90,000 | 4.1 | Dutch. |

| 50,000 | 2.3 | Canadian.[17] |

| 50,000 | 2.3 | Born in England. |

| 40,000 | 1.8 | French or French Canadian. About half were born in the United States of America, the other half in Quebec.[17] |

| 20,000 | 0.9 | Nordic (Norwegian, Swedish, Finnish, and Danish). |

| 7,000 | 0.3 | Italian |

| 7,000 | 0.3 | Jewish |

| 6,000 | 0.2 | Mexican |

| 5,000 | 0.2 | Polish (many of whom served in the Polish Legion of Brig. Gen. Włodzimierz Krzyżanowski) |

| 4,000 | 0.1 | Native Americans, mostly Lenape, Pamunkey, Lumbee, Seneca and Muscogee |

| 295,000 | 6.4 | Several hundred of other various nationalities |

Many immigrant soldiers formed their own regiments, such as the Irish Brigade (69th New York, 63rd New York, 88th New York, 28th Massachusetts, 116th Pennsylvania); the Swiss Rifles (15th Missouri); the Gardes de Lafayette (55th New York); the Garibaldi Guard (39th New York); the Martinez Militia (1st New Mexico); the Polish Legion (58th New York); the German Rangers; Sigel Rifles (52nd New York, inheriting the 7th); the Cameron Highlanders (79th New York Volunteer Infantry); and the Scandinavian Regiment (15th Wisconsin). But for the most part, the foreign-born soldiers were scattered as individuals throughout units.[18]

For comparison, the Confederate Army was not very diverse: 91% of Confederate soldiers were native born white men and only 9% were foreign-born white men, Irish being the largest group with others including Germans, French, Mexicans (though most of them simply happened to have been born when the Southwest was still part of Mexico), and British. Some Confederate propaganda condemned foreign-born soldiers in the Union Army, likening them to the hated Hessians of the American Revolution. Also, a relatively small number of Native Americans (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Creek) fought for the Confederacy.

Army administration and issues

Various organizational and administrative issues arose during the war, which had a major effect on subsequent military procedures.

.jpg.webp)

Blacks in the army

The inclusion of blacks as combat soldiers became a major issue. Eventually, it was realized, especially after the valiant effort of the 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry in the Battle of Fort Wagner, that blacks were fully able to serve as competent and reliable soldiers. This was partly due to the efforts of Robert Smalls, who, while still a slave, won fame by defecting from the Confederacy, and bringing a Confederate transport ship which he was piloting. He later met with Edwin Stanton, Secretary of War, to argue for including blacks in combat units. This led to the formation of the first combat unit for black soldiers, the 1st South Carolina Volunteers. Regiments for black soldiers were eventually referred to as United States Colored Troops. Black Soldiers were paid less than white Soldiers until late in the war and were, in general, treated harshly.

Unit supplies

Battlefield supplies were a major problem. They were greatly improved by new techniques in preserving food and other perishables, and in transport by railroad. General Montgomery C. Meigs was one of the most important Union Army leaders in this field.

Military tactics

The Civil War drove many innovations in military tactics.[19] W. J. Hardee published the first revised infantry tactics for use with modern rifles in 1855. However, even these tactics proved ineffective in combat, as it involved massed volley fire, in which entire units (primarily regiments) would fire simultaneously. These tactics had not been tested before in actual combat, and the commanders of these units would post their soldiers at incredibly close range, compared to the range of the rifled musket, which led to very high mortality rates. In a sense, the weapons had evolved beyond the tactics, which would soon change as the war drew to a close.[20] Military railways, occasionally used in earlier wars, provided mass movement of troops. The electric telegraph was used by both sides, which enabled political and senior military leaders to pass orders to and receive reports from commanders in the field.[21]

There were many other innovations brought by necessity. Generals were forced to reexamine the offensive minded tactics developed during the Mexican–American War where attackers could mass to within 100 yards of the defensive lines, the maximum effective range of smoothbore muskets. Attackers would have to endure one volley of inaccurate smoothbore musket fire before they could close with the defenders. But by the Civil War, the smoothbores had been replaced with rifled muskets, using the quick loadable minié ball, with accurate ranges up to 900 yards. Defense now dominated the battlefield. Now attackers, whether advancing in ordered lines or by rushes, were subjected to three or four aimed volleys before they could get among the defenders. This made offensive tactics that were successful only 20 years before nearly obsolete.[22]

Desertions and draft riots

Desertion was a major problem for both sides. The daily hardships of war, forced marches, thirst, suffocating heat, disease, delay in pay, solicitude for family, impatience at the monotony and futility of inactive service, panic on the eve of battle, the sense of war-weariness, the lack of confidence in commanders, and the discouragement of defeat (especially early on for the Union Army), all tended to lower the morale of the Union Army and to increase desertion.[23][24]

In 1861 and 1862, the war was going badly for the Union Army and there were, by some counts, 180,000 desertions. In 1863 and 1864, the bitterest two years of the war, the Union Army suffered over 200 desertions every day, for a total of 150,000 desertions during those two years. This puts the total number of desertions from the Union Army during the four years of the war at nearly 350,000. Using these numbers, 15% of Union soldiers deserted during the war. Official numbers put the number of deserters from the Union Army at 200,000 for the entire war, or about 8% of Union Army soldiers. Since desertion is defined as being AWOL for 30 or more days and some soldiers returned within that time period, as well as some deserters being labeled missing-in-action or vice versa, accurate counts are difficult to determine. Many historians estimate the "real" desertion rate in the Union Army as between 9–12%.[25] About 1 out of 3 deserters returned to their regiments, either voluntarily or after being arrested and being sent back. Many of the desertions were by "professional" bounty men, men who would enlist to collect the often large cash bonuses and then desert at the earliest opportunity to do the same elsewhere. If not caught and executed, it could prove a very lucrative criminal enterprise.[26][27]

The Irish were the main participants in the famous "New York Draft riots" of 1863.[28] Stirred up by the instigating rhetoric of Democratic politicians,[29] the Irish had shown the strongest support for Southern aims prior to the start of the war and had long opposed abolitionism and the free black population, regarding them as competition for jobs and blaming them for driving down wages. Alleging that the war was merely an upper class abolitionist war to free slaves who might move north and compete for jobs and housing, the poorer classes did not welcome a draft, especially one from which a richer man could buy an exemption. The poor formed clubs that would buy exemptions for their unlucky members. As a result of the Enrollment Act, rioting began in several Northern cities, the most heavily hit being New York City. A mob reported as consisting principally of Irish immigrants rioted in the summer of 1863, with the worst violence occurring in July during the Battle of Gettysburg. The mob set fire to everything from African American churches and an orphanage for "colored children" as well as the homes of certain prominent Protestant abolitionists. A mob was reportedly repulsed from the offices of the staunchly pro-Union New York Tribune by workers wielding and firing two Gatling guns. The principal victims of the rioting were African Americans and activists in the anti-slavery movement. Not until victory was achieved at Gettysburg could the Union Army be sent in; some units had to open fire to quell the violence and stop the rioters. By the time the rioting was over, perhaps up to 1,000 people had been killed or wounded.[30] There were a few small scale draft riots in rural areas of the Midwest and in the coal regions of Pennsylvania.[31][32]

See also

- American Civil War Corps Badges

- Commemoration of the American Civil War

- Grand Army of the Republic

- Irish Americans in the American Civil War

- German Americans in the American Civil War

- Hispanics in the American Civil War

- Italian Americans in the Civil War

- Native Americans in the American Civil War

- Military history of African Americans

- Southern Unionists

- Uniform of the Union Army

- United States National Cemeteries

- Army of the Frontier

- Army of the Southwest

- I Corps

- II Corps

- III Corps

- IV Corps

- V Corps

- VI Corps

- VII Corps

- VIII Corps

- IX Corps

- X Corps

- XI Corps

- XII Corps

- XIII Corps

- XIV Corps

- XV Corps

- XVI Corps

- XVII Corps

- XVIII Corps

- XIX Corps

- XX Corps

- XXI Corps

- XXII Corps

- XXIII Corps

- XXIV Corps

- XXV Corps

- Cavalry Corps

Notes

- "Civil War Facts". American Battlefield Trust.

- McPherson, pp.36–37.

- Civil War Casualties

- Newell, Clayton R. The Regular Army before the Civil War, 1845–1860 (PDF). US Army Campaigns of the Civil War. US Army, Center of Military History. pp. 50, 52.

- Crofts, Daniel W. CIVIL WAR SESQUICENTENNIAL: Unionism. digitalcommons.lsu.edu. Retrieved January 29, 2021

- Hattaway & Jones, pp. 9–10.

- The Civil War Book of Lists, p. 56

- "Civil War Army Organization and Rank". North Carolina Museum of History. Archived from the original on June 27, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2012.

- Eicher, pp. 37–38.

- McPherson, James M. (1997). For Cause and Comrades: Why Men Fought in the Civil War. New York City: Oxford University Press, Inc. p. 118. ISBN 0-19-509-023-3. OCLC 34912692. Retrieved March 10, 2016.

While restoration of the Union was the main goal for which they fought, they became convinced that this goal was unattainable without striking against slavery.

- Sanitary Commission Report, 1869

- Chippewa County, Wisconsin Past and Present, Volume II. Chicago: S.J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1913. p. 258.

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers (2000)

- McPherson, James M.; Lamb, Brian (May 22, 1994). "James McPherson: What They Fought For, 1861–1865". Booknotes. National Cable Satellite Corporation. Archived from the original on March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 9, 2016.

About 180,000 black soldiers and an estimated 10,000 black sailors fought in the Union Army and Navy, all of them in late 1862 or later, except for some blacks who enrolled in the Navy earlier.

- "General Orders No. 14". Civil War on the Western Border: The Missouri-Kansas Conflict, 1855–1865. Kansas City: The Kansas City Public Library. Archived from the original on November 5, 2014. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

[V]ery few blacks serve in the Confederate armed forces, as compared to hundreds of thousands who serve for the Union.

- Foner, Eric (October 27, 2010). "Book Discussion on The Fiery Trial". C-SPAN. Washington, D.C. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- Loewen, James W. (2007). Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong. New York: The New Press. ISBN 9781595586537. Retrieved March 8, 2016.

Forty thousand Canadians alone, some of them black, came south to volunteer for the Union cause.

- The 52nd New York State Volunteers

- Perry D. Jamieson, Crossing the Deadly Ground: United States Army Tactics, 1865–1899 (2004)

- John K. Mahon, "Civil War Infantry Assault Tactics." Military Affairs (1961): 57–68.

- Paddy Griffith, Battle tactics of the civil war (Yale University Press, 1989)

- Earl J. Hess (2015). Civil War Infantry Tactics: Training, Combat, and Small-Unit Effectiveness. LSU Press. p. 1. ISBN 9780807159385.

- Ella Lonn, Desertion During the Civil War (U of Nebraska Press, 1928)

- Chris Walsh, "'Cowardice Weakness or Infirmity, Whichever It May Be Termed': A Shadow History of the Civil War." Civil War History (2013) 59#4 pp: 492–526.Online

- "Desertion (Confederate) during the Civil War". encyclopediavirginia.org. Retrieved October 13, 2017.

- Shannon Smith Bennett, "Draft Resistance and Rioting." in Maggi M. Morehouse and Zoe Trodd, eds., Civil War America: A Social and Cultural History with Primary Sources (2013) ch 1

- Peter Levine, "Draft evasion in the North during the Civil War, 1863–1865." Journal of American History (1981): 816–834. online Archived March 4, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- Adrian Cook, The armies of the streets: the New York City draft riots of 1863 (1974).

- McPherson, James M. (1996). Drawn with the Sword: Reflections on the American Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc. pp. 91–92.

Rioters were mostly Irish Catholic immigrants and their children. They mainly attacked the members of New York's small black population. For a year, Democratic leaders had been telling their Irish-American constituents that the wicked 'Black Republicans' were waging the war to free the slaves who would come north and take away the jobs of Irish workers. The use of black stevedores as scabs in a recent strike by Irish dockworkers made this charge seem plausible. The prospect of being drafted to fight to free the slaves made the Irish even more receptive to demogogic rhetoric.

- Iver Bernstein, The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (1990)

- Shannon M. Smith, "Teaching Civil War Union Politics: Draft Riots in the Midwest." OAH Magazine of History (2013) 27#2 pp: 33–36. online

- Kenneth H. Wheeler, "Local Autonomy and Civil War Draft Resistance: Holmes County, Ohio." Civil War History. v.45#2 1999. pp 147+ online edition

References

- Eicher, John H., and David J. Eicher. Civil War High Commands. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-8047-3641-3.

- Grant, Ulysses S. Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant. 2 vols. Charles L. Webster & Company, 1885–86. ISBN 0-914427-67-9.

- Glatthaar, Joseph T. Forged in Battle: The Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers. New York: Free Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0-02-911815-3.

- Hattaway, Herman, and Archer Jones. How the North Won: A Military History of the Civil War. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1983. ISBN 0-252-00918-5.

- McPherson, James M. What They Fought For, 1861–1865. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0-8071-1904-4.

Further reading

- Bledsoe, Andrew S. Citizen-Officers: The Union and Confederate Volunteer Junior Officer Corps in the American Civil War. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0-8071-6070-1.

- Canfield, Daniel T. "Opportunity Lost: Combined Operations and the Development of Union Military Strategy, April 1861 – April 1862." Journal of Military History 79.3 (2015).

- Kahn, Matthew E., and Dora L. Costa. "Cowards and Heroes: Group Loyalty in the American Civil War." Quarterly journal of economics 2 (2003): 519–548. online version

- Nevins, Allan. The War for the Union. Vol. 1, The Improvised War 1861–1862. The War for the Union. Vol. 2, War Becomes Revolution 1862–1863. Vol. 3, The Organized War 1863–1864. Vol. 4, The Organized War to Victory 1864–1865. (Charles Scribner's Sons, 1960–71. ISBN 1-56852-299-1.)

- Prokopowicz, Gerald J. All for the Regiment: the Army of the Ohio, 1861–1862 (UNC Press, 2014). online

- Shannon, Fred A. The Organization and Administration of the Union Army 1861–1865. 2 vols. Gloucester, MA: P. Smith, 1965. OCLC 428886. First published 1928 by A.H. Clark Co.

- Welcher, Frank J. The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 1, The Eastern Theater. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-253-36453-1; . The Union Army, 1861–1865 Organization and Operations. Vol. 2, The Western Theater. (1993). ISBN 0-253-36454-X.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Union Army. |

- Civil War Home: Ethnic groups in the Union Army

- "The Common Soldier", HistoryNet

- A Manual of Military Surgery, by Samuel D. Gross, MD (1861), the manual used by doctors in the Union Army.

- Union Army Historical Pictures

- U.S. Civil War Era Uniforms and Accoutrements

- Louis N. Rosenthal lithographs, depicting over 50 Union Army camps, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- Official Army register of the Volunteer Force 1861; 1862; 1863; 1864; 1865

- Civil War National Cemeteries

- Christian Commission of Union Dead

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols 1–8

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols 9–12

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols 13–15

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols. 16–17

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vol. 18

- Roll of Honor: names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vol. 19

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols. 20–21

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols, 22–23

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in Defense of the Union Vols. 24–27

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers who died in defense of the Union Vol. XXVII

.svg.png.webp)