Fluorouracil

Fluorouracil (5-FU), sold under the brand name Adrucil among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat cancer.[2] By injection into a vein it is used for colon cancer, esophageal cancer, stomach cancer, pancreatic cancer, breast cancer, and cervical cancer.[2] As a cream it is used for actinic keratosis, basal cell carcinoma, and skin warts.[3][4]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌflʊəroʊˈjʊərəsɪl/[1] |

| Trade names | Adrucil, Carac, Efudex, Efudix, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682708 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | IV (infusion or bolus) and topical |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 28 to 100% |

| Protein binding | 8 to 12% |

| Metabolism | Intracellular and liver (CYP-mediated) |

| Elimination half-life | 16 minutes |

| Excretion | kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.078 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C4H3FN2O2 |

| Molar mass | 130.078 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 282–283 °C (540–541 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

When used by injection most people develop side effects.[2] Common side effects include inflammation of the mouth, loss of appetite, low blood cell counts, hair loss, and inflammation of the skin.[2] When used as a cream, irritation at the site of application usually occurs.[3] Use of either form in pregnancy may harm the baby.[2] Fluorouracil is in the antimetabolite and pyrimidine analog families of medications.[5][6] How it works is not entirely clear but believed to involve blocking the action of thymidylate synthase and thus stopping the production of DNA.[2]

Fluorouracil was patented in 1956 and came into medical use in 1962.[7] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[8]

Medical uses

Fluorouracil has been given systemically for anal, breast, colorectal, oesophageal, stomach, pancreatic and skin cancers (especially head and neck cancers).[9] It has also been given topically (on the skin) for actinic keratoses, skin cancers and Bowen's disease[9] and as eye drops for treatment of ocular surface squamous neoplasia.[10] Other uses include ocular injections into a previously created trabeculectomy bleb to inhibit healing and cause scarring of tissue, thus allowing adequate aqueous humor flow to reduce intraocular pressure.

Contraindications

It is contraindicated in patients that are severely debilitated or in patients with bone marrow suppression due to either radiotherapy or chemotherapy.[11] It is likewise contraindicated in pregnant or breastfeeding women.[11] It should also be avoided in patients that do not have malignant illnesses.[11]

Adverse effects

Adverse effects by frequency include:[9][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

During systemic use

Common (> 1% frequency):

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea (see below for details)

- Mucositis

- Headache

- Myelosuppression (see below for details)

- Alopecia (hair loss)

- Photosensitivity

- Hand-foot syndrome

- Maculopapular eruption

- Itch

- Cardiotoxicity (see below for details)

- Persistent hiccups

- Mood disorders (irritability, anxiety, depression)

Uncommon (0.1–1% frequency):

- Oesophagitis

- GI ulceration and bleeding

- Proctitis

- Nail disorders

- Vein pigmentation

- Confusion

- Cerebellar syndrome

- Encephalopathy

- Visual changes

- Photophobia

- Lacrimation (the expulsion of tears without any emotional or physiologic reason)

Rare (< 0.1% frequency):

- Anaphylaxis

- Allergic reactions

- Fever without signs of infection

Diarrhea is severe and may be dose-limiting and is exacerbated by co-treatment with calcium folinate.[9] Neutropenia tends to peak about 9–14 days after beginning treatment.[9] Thrombocytopenia tends to peak about 7–17 days after the beginning of treatment and tends to recover about 10 days after its peak.[9] Cardiotoxicity is a fairly common side effect, but usually this cardiotoxicity is just angina or symptoms associated with coronary artery spasm, but in about 0.55% of those receiving the drug will develop life-threatening cardiotoxicity.[19] Life-threatening cardiotoxicity includes: arrhythmias, ventricular tachycardia and cardiac arrest, secondary to transmural ischaemia.[19]

During topical use

Common (> 1% frequency):

- Local pain

- Itchiness

- Burning

- Stinging

- Crusting

- Weeping

- Dermatitis

- Photosensitivity

Uncommon (0.1–1% frequency):

- hyper- or hypopigmentation

- Scarring

Potential overdose

There is very little difference between the minimum effective dose and maximum tolerated dose of 5-FU, and the drug exhibits marked individual pharmacokinetic variability.[21][22][23] Therefore, an identical dose of 5-FU may result in a therapeutic response with acceptable toxicity in some patients and unacceptable and possibly life-threatening toxicity in others.[21] Both overdosing and underdosing are of concern with 5-FU, although several studies have shown that the majority of colorectal cancer patients treated with 5-FU are underdosed based on today's dosing standard, body surface area (BSA).[24][25][26][27] The limitations of BSA-based dosing prevent oncologists from being able to accurately titer the dosage of 5-FU for the majority of individual patients, which results in sub-optimal treatment efficacy or excessive toxicity.[24][25]

Numerous studies have found significant relationships between concentrations of 5-FU in blood plasma and both desirable or undesirable effects on patients.[28][29] Studies have also shown that dosing based on the concentration of 5-FU in plasma can greatly increase desirable outcomes while minimizing negative side effects of 5-FU therapy.[24][30] One such test that has been shown to successfully monitor 5-FU plasma levels and which "may contribute to improved efficacy and safety of commonly used 5-FU-based chemotherapies" is the My5-FU test.[26][31][32]

Interactions

Its use should be avoided in patients receiving drugs known to modulate dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (such as the antiviral drug sorivudine).[11] It may also increase the INR and prothrombin times in patients on warfarin.[11] Fluorouracil's efficacy is decreased when used alongside allopurinol, which can be used to decrease fluorouracil induced stomatitis through use of allopurinol mouthwash.[33]

Pharmacology

Pharmacogenetics

The dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) enzyme is responsible for the detoxifying metabolism of fluoropyrimidines, a class of drugs that includes 5-fluorouracil, capecitabine, and tegafur.[34] Genetic variations within the DPD gene (DPYD) can lead to reduced or absent DPD activity, and individuals who are heterozygous or homozygous for these variations may have partial or complete DPD deficiency; an estimated 0.2% of individuals have complete DPD deficiency.[34][35] Those with partial or complete DPD deficiency have a significantly increased risk of severe or even fatal drug toxicities when treated with fluoropyrimidines; examples of toxicities include myelosuppression, neurotoxicity and hand-foot syndrome.[34][35]

Mechanism of action

5-FU acts in several ways, but principally as a thymidylate synthase (TS) inhibitor. Interrupting the action of this enzyme blocks synthesis of the pyrimidine thymidylate (dTMP), which is a nucleotide required for DNA replication. Thymidylate synthase methylates deoxyuridine monophosphate (dUMP) to form thymidine monophosphate (dTMP). Administration of 5-FU causes a scarcity in dTMP, so rapidly dividing cancerous cells undergo cell death via thymineless death.[36] Calcium folinate provides an exogenous source of reduced folinates and hence stabilises the 5-FU-TS complex, hence enhancing 5-FU's cytotoxicity.[37]

History

In 1954, Abraham Cantarow and Karl Paschkis found liver tumors absorbed radioactive uracil more readily than normal liver cells. Charles Heidelberger, who had earlier found that fluorine in fluoroacetic acid inhibited a vital enzyme, asked Robert Duschinsky and Robert Schnitzer at Hoffmann-La Roche to synthesize fluorouracil.[38] Some credit Heidelberger and Duschinsky with the discovery that 5-fluorouracil markedly inhibited tumors in mice.[39] The original 1957 report[40][41] in Nature has Heidelberger as lead author, along with N. K. Chaudhuri, Peter Danneberg, Dorothy Mooren, Louis Griesbach, Robert Duschinsky, R. J. Schnitzer, E. Pleven, and J. Scheiner.[42] In 1958, Anthony R. Curreri, Fred J. Ansfield, Forde A. McIver, Harry A. Waisman, and Charles Heidelberger reported the first clinical findings of 5-FU's activity in cancer in humans.[43]

Natural analogues

In 2003, scientists isolated 5-fluorouracil derivatives, closely related compounds, from the marine sponge, Phakellia fusca collected around the Yongxing Island of the Xisha Islands in the South China Sea. This is significant because fluorine-containing organic compounds are rare in nature, and also because manmade anticancer drugs are not frequently found to have analogues in nature.[44]

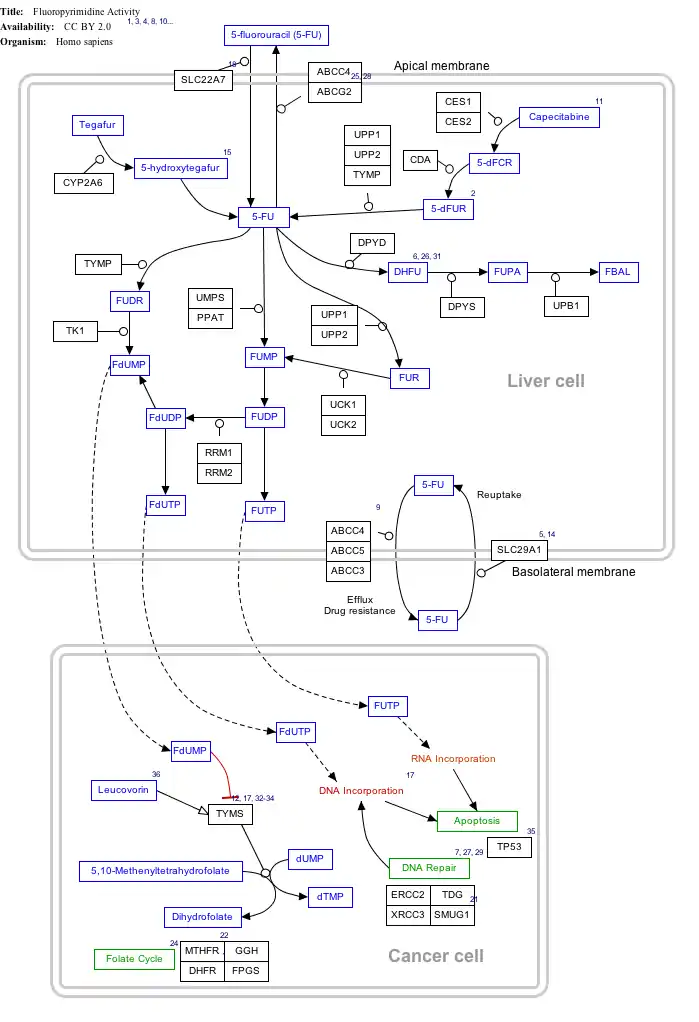

Interactive pathway map

Click on genes, proteins and metabolites below to link to respective articles.[§ 1]

- The interactive pathway map can be edited at WikiPathways: "FluoropyrimidineActivity_WP1601".

Names

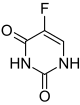

The name "fluorouracil" is the INN, USAN, USP name, and BAN. The form "5-fluorouracil" is often used; it shows that there is a fluorine atom on the 5th carbon of a uracil ring.

References

- "Fluorouracil – Definition and More from the Free Merriam-Webster Dictionary". Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 2014-11-19.

- "Fluorouracil". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- "Fluorouracil topical". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- Moore, AY (2009). "Clinical applications for topical 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of dermatological disorders". The Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 20 (6): 328–35. doi:10.3109/09546630902789326. PMID 19954388.

- British national formulary : BNF 69 (69 ed.). British Medical Association. 2015. p. 590. ISBN 9780857111562.

- Airley, Rachel (2009). Cancer Chemotherapy: Basic Science to the Clinic. John Wiley & Sons. p. 76. ISBN 9780470092569. Archived from the original on 2017-11-05.

- Fischer, Janos; Ganellin, C. Robin (2006). Analogue-based Drug Discovery. John Wiley & Sons. p. 511. ISBN 9783527607495. Archived from the original on 2017-09-11.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- Joag, Madhura G.; Sise, Adam; Murillo, Juan Carlos; Sayed-Ahmed, Ibrahim Osama; Wong, James R.; Mercado, Carolina; Galor, Anat; Karp, Carol L. (2016-03-27). "Topical 5-Fluorouracil 1% as Primary Treatment for Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia". Ophthalmology. 123 (7): 1442–1448. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.034. ISSN 1549-4713. PMC 4921289. PMID 27030104.

- "Fluorouracil 50 mg/ml Injection – Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. Hospira UK Ltd. 24 August 2011. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "DBL Fluorouracil Injection BP" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Hospira Australia Pty Ltd. 21 June 2012. Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "ADRUCIL (fluorouracil) injection [Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc.]". DailyMed. Teva Parenteral Medicines, Inc. August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "Efudex, Carac (fluorouracil topical) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- "Adrucil (fluorouracil) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 24 January 2014.

- Ha, JH; Hwang, DY; Yu, J; Park, DH; Ryu, SH (2011). "Onset of Manic Episode during Chemotherapy with 5-Fluorouracil". Psychiatry Investig. 8 (1): 71–3. doi:10.4306/pi.2011.8.1.71. PMC 3079190. PMID 21519541.

- Park H. J., Choi Y. T., Kim I. H., Hah J. C.; A case of reversible dementia associated with depression in a patient on 5-FU or its analogue drugs. J. Korean Neuropsychiatr. Assoc. 1987;30:199–202.

- MedsFacts meta-analysis covering adverse side effect reports of 5fu(fluorouracil) patients who developed hiccups Archived 2014-09-05 at the Wayback Machine at MedsFact, 2013

- Brayfield, A, ed. (9 January 2017). "Fluorouracil: Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference". MedicinesComplete. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- "Adrucil (Fluorouracil) Injection [TEVA Parenteral Medicines, Inc.]". Archived from the original on 2014-08-14.

- Gamelin, E.; Boisdron-Celle, M. (1999). "Dose monitoring of 5-fluorouracil in patients with colorectal or head and neck cancer—status of the art". Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 30 (1): 71–79. doi:10.1016/s1040-8428(98)00036-5. PMID 10439055.

- Felici A.; J. Verweij; Sparreboom A. (2002). "Dosing strategies for anticancer drugs: the good, the bad and body-surface area". Eur J Cancer. 38 (13): 1677–84. doi:10.1016/s0959-8049(02)00151-x. PMID 12175683.

- Baker S. D.; Verweij J.; Rowinsky E. K.; Donehower R. C.; Schellens J. H.; Grochow L. B.; Sparreboom A. (2002). "Role of body surface area in dosing of investigational anticancer agents in adults, 1991–2001". J Natl Cancer Inst. 94 (24): 1883–8. doi:10.1093/jnci/94.24.1883. PMID 12488482.

- Capitain O.; Asevoaia A.; Boisdron-Celle M.; Poirier A. L.; Morel A.; Gamelin E. (2012). "Individual Fluorouracil Dose Adjustment in FOLFOX Based on Pharmacokinetic Follow-Up Compared With Conventional Body-Area-Surface Dosing: A Phase II, Proof-of-Concept Study". Clin. Colorectal Cancer. 11 (4): 263–267. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2012.05.004. PMID 22683364.

- Saam, J; Critchfield G. C.; Hamilton S. A.; Roa B. B.; Wenstrup R. J.; Kaldate R. R. (2011). "Body surface area-based dosing of 5-fluoruracil results in extensive interindividual variability in 5-fluorouracil exposure in colorectal cancer patients on FOLFOX regimens". Clin Colorectal Cancer. 10 (3): 203–6. doi:10.1016/j.clcc.2011.03.015. PMID 21855044.

- Beumer J. H.; Boisdron-Celle M.; Clarke W.; Courtney J. B.; Egorin M. J.; Gamelin E; Harney R. L.; Hammett-Stabler C; Lepp S.; Li Y.; Lundell G. D.; McMillin G.; Milano G.; Salamone S. J. (2009). "Multicenter evaluation of a novel nanoparticle immunoassay for 5-fluorouracil on the Olympus AU400 analyzer". Ther. Drug Monit. 31 (6): 688–94. doi:10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181b9b8c0. PMID 19935361. S2CID 220558482.

- Goldberg R. M.; Rothenberg M. L.; Van Cutsem E.; Benson A. B. 3rd; Blanke C. D.; Diasio R. B.; Grothey A.; Lenz H. J.; Meropol N. J.; Ramanathan R. K.; Becerra C. H.; Wickham R.; Armstrong D.; Viele C. (2007). "The Continuum of Care: A Paradigm for the Management of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer". The Oncologist. 12 (1): 38–50. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.12-1-38. PMID 17227899.

- Ploylearmsaeng, S.-a.; Fuhr U.; Jetter A. (2006). "How may Anticancer Chemotherapy with Fluorouracil be Individualised?". Clin Pharmacokinet. 45 (6): 567–92. doi:10.2165/00003088-200645060-00002. PMID 16719540. S2CID 36534309.

- van Kuilenburg, A. B.; Maring J. G. (2013). "Evaluation of 5-fluorouracil pharmacokinetic models and therapeutic drug monitoring in cancer patients". Pharmacogenomics. 14 (7): 799–811. doi:10.2217/pgs.13.54. PMID 23651027.

- Gamelin E. C.; Delva R.; Jacob J.; Merrouche Y; Raoul J. L.; Pezet D.; Dorval E.; Piot G.; Morel A.; Boisdron-Celle M. (2008). "Individual fluorouracil dose adjustment based on pharmacokinetic follow-up compared with conventional dosage: Results of a multicenter randomized trial of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer". J. Clin. Oncol. 26 (13): 2099–2105. doi:10.1200/jco.2007.13.3934. PMID 18445839. S2CID 9557055.

- "Customizing Chemotherapy for Better Cancer Care". MyCare Diagnostics. Archived from the original on 2014-04-28.

- "A Brief History of BSA Dosing". MyCare Diagnostics. Archived from the original on 2014-04-28.

- Porta C, Moroni M, Nastasi G (1994). "Allopurinol mouthwashes in the treatment of 5-fluorouracil-induced stomatitis". Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 17 (3): 246–7. doi:10.1097/00000421-199406000-00014. PMID 8192112. S2CID 26844431.

- Caudle, KE; Thorn, CF; Klein, TE; Swen, JJ; McLeod, HL; Diasio, RB; Schwab, M (December 2013). "Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium guidelines for dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase genotype and fluoropyrimidine dosing". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 94 (6): 640–5. doi:10.1038/clpt.2013.172. PMC 3831181. PMID 23988873.

- Amstutz, U; Froehlich, TK; Largiadèr, CR (September 2011). "Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase gene as a major predictor of severe 5-fluorouracil toxicity". Pharmacogenomics. 12 (9): 1321–36. doi:10.2217/pgs.11.72. PMID 21919607.

- Longley D. B.; Harkin D. P.; Johnston P. G. (May 2003). "5-fluorouracil: mechanisms of action and clinical strategies". Nat. Rev. Cancer. 3 (5): 330–8. doi:10.1038/nrc1074. PMID 12724731. S2CID 4357553.

- Álvarez, P.; Marchal, J. A.; Boulaiz, H.; Carrillo, E.; Vélez, C.; Rodríguez-Serrano, F.; Melguizo, C.; Prados, J.; Madeddu, R.; Aranega, A. (February 2012). "5-Fluorouracil derivatives: a patent review". Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents. 22 (2): 107–123. doi:10.1517/13543776.2012.661413. PMID 22329541. S2CID 2793746.

- Sneader W. (2005). Drug Discovery, p. 255.

- Cohen, Seymour (30 January 2008). "50 years ago in cell biology: A virologist recalls his work on cell growth inhibition". The Scientist. Archived from the original on 19 September 2010.

- Chu E (September 2007). "Ode to 5-Fluorouracil". Clinical Colorectal Cancer. 6 (9): 609. doi:10.3816/CCC.2007.n.029. Archived from the original on 2012-07-14.

- National Academy of Sciences, Biographical Memoirs,80:135

- Heidelberger C.; Chaudhuri N. K.; Danneberg P.; et al. (March 1957). "Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds". Nature. 179 (4561): 663–6. Bibcode:1957Natur.179..663H. doi:10.1038/179663a0. PMID 13418758. S2CID 4296069.

- Jordan, V. Craig (February 2016). "A Retrospective: On Clinical Studies with 5-Fluorouracil". Cancer Research. American Association for Cancer Research. 76 (4): 767–768. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0150. PMID 26880809.

- Xu, Xiao-Hua; Yao, Guang-Min; Li, Yan-Ming; Lu, Jian-Hua; Lin, Chang-Jiang; Wang, Xin; Kong, Chui-Hua (2003-02-01). "5-Fluorouracil derivatives from the sponge Phakellia fusca". Journal of Natural Products. 66 (2): 285–288. doi:10.1021/np020034f. ISSN 0163-3864. PMID 12608868.

Further reading

- Dean L (2016). "Fluorouracil Therapy and DPYD Genotype". In Pratt VM, McLeod HL, Rubinstein WS, et al. (eds.). Medical Genetics Summaries. National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). PMID 28520376. Bookshelf ID: NBK395610.

- Latchman, Jessica; Guastella, Ann; Tofthagen, Cindy (1 October 2014). "5-Fluorouracil Toxicity and Dihydropyrimidine Dehydrogenase Enzyme: Implications for Practice". Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 18 (5): 581–585. doi:10.1188/14.CJON.581-585. PMC 5469441. PMID 25253112.

External links

- "Fluorouracil". Drug Information Portal. U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- "Fluorouracil Topical". MedlinePlus.