Fred Merkle

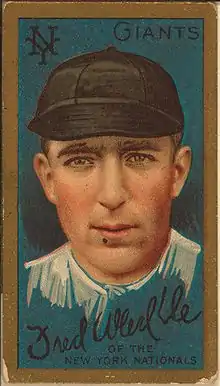

Carl Frederick Rudolf Merkle (December 20, 1888 – March 2, 1956), also documented as "Frederick Charles Merkle,"[1] and nicknamed "Bonehead",[2] was an American first baseman in Major League Baseball from 1907 to 1926. Although he had a lengthy career, he is best remembered for a controversial base-running mistake he made while still a teenager.

| Fred Merkle | |||

|---|---|---|---|

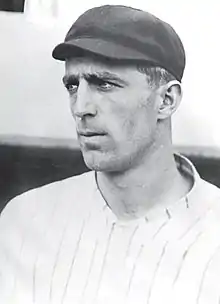

Merkle in 1908 | |||

| First baseman | |||

| Born: December 20, 1888 Watertown, Wisconsin | |||

| Died: March 2, 1956 (aged 67) Daytona Beach, Florida | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| September 21, 1907, for the New York Giants | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| September 26, 1926, for the New York Yankees | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Batting average | .273 | ||

| Home runs | 82 | ||

| Runs batted in | 733 | ||

| Stolen bases | 272 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

Career

Born in Watertown, Wisconsin, to Ernst Merkle, a Swiss immigrant, and Amalie Thielmann Merkle, a German American,[3] he was raised in Toledo, Ohio. Merkle played his first Major League game at the age of 18, with the New York Giants in 1907. He was still the youngest player in the National League, and used mostly as a pinch hitter, at the time of his infamous "boner" in 1908. Merkle became the Giants' regular first baseman by 1910 and contributed in that role to three straight pennant winners from 1911 to 1913. He was traded to the Brooklyn Robins in August 1916 and played in his fourth World Series that year. In April 1917, the Robins sold Merkle to the Chicago Cubs, the team against which he had made his infamous play in 1908, with whom he continued as the regular first baseman through 1920. In 1918 with the Cubs, Merkle played in his fifth World Series in eight years, though he never won the championship.

From 1921 to 1925, Merkle was the regular first baseman for Rochester in the International League. He returned to the Major Leagues in mid-1925, when he was acquired by the New York Yankees, but appeared in only seven games with the Yankees that year and one in 1926. After one year back in the International League as player-manager for Reading in 1927, Merkle retired.

Fred Merkle was inducted into the International League Hall of Fame in 1953.

The "Boner"

On September 23, 1908, while playing for the New York Giants in a game against the Chicago Cubs, while he was 19 years old (the youngest player in the National League), Merkle committed a base-running error that became known as "Merkle's Boner" and earned him the nickname "Bonehead".

In the bottom of the 9th inning, Merkle came to bat with two outs, and the score tied 1–1. At the time, Moose McCormick was on first base. Merkle singled and McCormick advanced to third base. Al Bridwell, the next batter, followed with a single of his own. McCormick trotted to home plate, apparently scoring the winning run. The fans in attendance, under the impression that the game was over, ran onto the field to celebrate.

Meanwhile, Merkle ran to the Giants' clubhouse without touching second base.

Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers noticed this, and after retrieving a ball and touching second base, he appealed to umpire Hank O'Day, who later managed the Cubs, to call Merkle out. Since Merkle had not touched the base, the umpire called him out on a force play, meaning that McCormick's run did not count.

The run was therefore nullified, the Giants' victory erased, and the score of the game remained tied. Unfortunately, the thousands of fans on the field (as well as the growing darkness in the days long before large electric lights made night games possible) prevented resumption of the game, and it was declared a tie. The Giants and the Cubs ended the season tied for first place and had a rematch at the Polo Grounds, on October 8. The Cubs won this makeup game, 4–2, thus the National League pennant.

Varying accounts

Accounts vary as to whether Evers actually retrieved the game ball or not. Some versions of the story have him running to the outfield to retrieve the correct ball. Other versions have it that he shouted for the ball, which was relayed to him from the Cubs' dugout. Still other versions have it that Giants pitcher Joe McGinnity saw what was transpiring, and threw the game ball into the stands; thus, the ball that was picked up by or relayed to Evers was a different ball entirely. The New York Times account of the play recalls that Cubs manager and first baseman Frank Chance was the one who "grasped the situation" and directed that the ball be thrown to him covering second base.

At the time, running off the field without touching the base was common, as the rule allowing a force play after a potential game-winning run was not well known. However, Evers, who was noted as an avid student of the official rules of the game, had previously attempted the same play only a few weeks earlier, in Pittsburgh, with the same Hank O'Day umpiring. In that instance, O'Day had not seen whether the runner tagged second, so he declined Evers' appeal, but he apparently was alert to the possibility in the New York game. The outcome ensured that the rule was known to everyone afterward.

Aftermath

Giants manager John McGraw was furious at the league office, feeling his team was robbed of a victory (and a pennant), but he never blamed Merkle for his mistake.

The Cubs went on to win the 1908 World Series. The team then went through a 108-year-long championship drought, before finally winning the World Series in 2016.

Bitter over the events of the controversial game, Merkle avoided baseball after his playing career ended in 1926. When he finally appeared at a Giants old-timers' game in 1950, he received a standing ovation.[4]

Fred Merkle is commemorated in his hometown of Watertown, Wisconsin. The city's primary high school baseball field at Washington Park is named Fred Merkle Field. Also, a black plaque honoring him was erected in the park on July 22, 2010. A second plaque in Watertown is on the grounds of the Octagon House.

Merkle's Bar and Grill in Chicago is named after Fred Merkle.[5]

Family life

Merkle and his wife Ethel Cynthia Brownson Merkle[1] enjoyed a long marriage, from 1914 to his death in 1956. The Merkles had three daughters: Marjorie, Jeannette, and Marianne.[6]

Other sports

In 1906, Merkle played football for the Toledo Athletic Association as an end. That season, the team was defeated by the Canton Bulldogs by a score of 31–0.

Death

Merkle died in Daytona Beach at age 67, and was interred there in Bellevue Cedar Hill Memory Gardens.[7] As Fred had before her, Ethel died in Daytona Beach, Florida, in December 1976.[8]

References

- Merkle, Ralph C. "The Merkle Family, Toledo". The Merkle Family, Toledo. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "Fred Merkle Statistics and History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved March 14, 2012.

- "Wisconsin, Births and Christenings". familysearch.org. Retrieved July 29, 2013.

- Sherman, Ed (Sep 23, 2008). "Sadly, one play defined Merkle's career". ESPN.com.

- http://www.merkleschicago.com/

- Stalker, David J. "Fred C. Merkle 1888 -1956". watertownhistory.org. Watertown Historical Society. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- The Baseball Necrology

- Kasbaum, Marianne. "Message Boards – Brownson". Ancestry. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

Further reading

- Cameron, MIke (2010). Public Bonehead, Private Hero: The Real Legacy of Baseball's Fred Merkle. Crystal Lake, Illinois: Sporting Chance Press. ISBN 978-0-9819342-1-1.

- Murphy, Cait (2007). Crazy '08: How a Cast of Cranks, Rogues, Boneheads, and Magnates Created the Greatest Year in Baseball History. New York: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-0-06-088937-1.

- Bell, Christopher (2002). Scapegoats : Baseballers Whose Careers Are Marked by One Fateful Play. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1381-6.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fred Merkle. |

- Career statistics and player information from Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors)

- Box score of the Merkle Boner game

- "Sadly, one play defined Merkle's career, life", by Ed Sherman, ESPN.com

- Fred Merkle at Find a Grave

- "Blondy Wallace and the Biggest Football Scandal Ever" (PDF). PFRA Annual. Professional Football Researchers Association. 5: 1–16. 1984. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 4, 2013.