Gamasoidosis

Gamasoidosis or dermanyssosis is a frequently unrecognized ectoparasitosis[2] and source of growing concern in human medicine,[3] occurring after contact with avian mites which infest canaries,[4] sparrows, starlings, pigeons[5] and poultry[6] and caused by two genera of mites, Ornithonyssus and Dermanyssus.[7] Avian mite species implicated include the red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae),[8] tropical fowl mite (Ornithonyssus bursa)[9] and northern fowl mite (Ornithonyssus sylviarum)[8]. Mite dermatitis is also associated with rodents infested with the tropical rat mite (Ornithonyssus bacoti),[10][11] spiny rat mite (Laelaps echidnina)[12] and house-mouse mite (Liponyssoides sanguineus), where the condition is known as rodent mite dermatitis.[13] Urban gamasoidosis is associated with window-sills, ventilation and air-conditioning intakes, rooves and eaves, which serve as shelters for nesting birds. Humans bitten by these mites experience a non-specific dermatitis with intense itching.[14][15]

| Gamasoidosis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Acariasis, Avian mite dermatitis or Bird mite dermatitis[1] |

| |

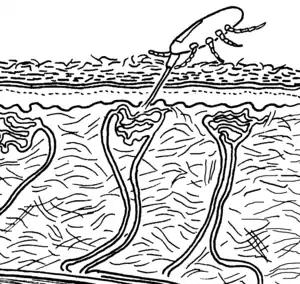

| Dermanyssus gallinae piercing skin with its long chelicerae to reach dermal capillaries (not to scale). | |

| Specialty | Dermatology |

Clinical signs

The most common symptoms are "itching and punctiform, erythematous papules"[14] with a size of "1–3 mm"[3] and a "central punctum",[16] the itching and irritation are reactions to the saliva the mites secrete when feeding.[9]

Bites are normally located in groups around the neck and body areas covered by clothes (waist, trunk, upper extremities and abdomen),[3][10][17] but can also be found on the legs,[14] finger webs, axillae, the groin, and buttocks.[17] If feeding occurs while a patient is sleeping, bedclothes and pillows may show red spots caused by droppings or crushed mites.[3]

D. gallinae is capable of infesting the ear canal, with symptoms including itching, internal inflammation and discharge.[18] It can also infest the scalp, with severe itching — particularly at night as the primary symptom[19] — as well as "the nares, orbits and eyelids, and genitourinary and rectal orifices.“[20]

Additional symptoms include pinpricks, secondary infections, scarring, hyperpigmentation as well as psychological trauma resulting in anxiety and depression.[21]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis can be challenging as the small size of avian mites make them "barely visible to the unaided eye".[22] Identification of the species is best carried out by a medical entomologist using a microscope,[8] positive identification of species is critical for recommendation of suitable treatment. Samples can be obtained using corrugated cardboard traps, left in infested areas.[23]

Diagnoses of gamasoidosis have a long history, with "cases [...] reported since the 17th century, documented in the leading medical literature since at least the 1920s."[24] Avian and rodent mites have been documented infesting residential buildings, work spaces, schools and hospitals.[10][24] Despite this, there is considered to be widespread ignorance and misinformation "regarding human infestation with D. gallinae across healthcare, science and pest control fields", which in turn has led to increasing numbers of infestations and a dangerous propagation of the disease.[21]

Due to it being an uncommon diagnosis, physicians are generally not aware of the condition,[3] meaning gamasoidosis may be misdiagnosed as scabies or pediculosis[25] or bites mistakenly identified as coming from bed bugs.[26] Many cases of gamasoidosis go unreported, suggesting that the actual incidence is higher than generally believed.[6] As a result, in cases of unexplained bites in residential areas, the involvement of D. gallinae should always be considered,[14] especially during late spring and early summer when wild birds make their nests.[17]

The life cycle of the mite is another important method of diagnosis.[21] Hematophagic mites generally feed at night[27] but may also feed during the day if the room is sufficiently dark.[28] Attacks in public and office buildings tend to occur during the daytime.[3] O. bursa is an exception as it generally remains on its hosts and will feed during the day.[29] D. gallinae may be commonly found in the bedroom or where the patient sleeps, as they prefer to stay close to their host for optimal feeding.[30] They are attracted to warm hiding places that simulate the body temperature of birds (e.g. pigeons 42 °C), "such as the electrical devices running in stand-by mode (e.g. laptop computers, television, radio clocks etc.)" which generate heat. As a result, "it is strongly recommended to check these electrical appliances for the mite detection".[14] D. gallinae generally visit their host for up to 1–2 hours, leave after completing their blood meal[14] and typically feed every 2–4 days.[24] They are able to move extremely quickly[16] and can take less than 1 second to bite, enough time to inject their saliva and to induce rash and itching.[14] They locate potential hosts through temperature changes,[14] vibration and CO

2.[31][32]

It has been hypothesized the D. gallinae is capable of 'learning'[33] "to associate non-host skin with a blood-meal if the host selection process permitted feeding."[24] Combined with a generalist approach to finding hosts and the capability of digesting non-avian blood could potentially explain their documented host expansion to mammals and humans.[24]

There is documented "co-occurrence of gamasoidosis and various immunosuppressive disorders"[24] and physicians should bear in mind that immunocompromised patients, patients that take corticosteroids, and patients with dementia may have a more severe infestation than healthy patients,[21] Despite this, while immunosuppression can "increase susceptibility, it is not necessarily a pre-requisite for infestation".[24]

Dermatoscopy can help to exclude the diagnosis of delusional parasitosis.[2]

Pets such as canaries,[14] cats,[34] dogs[35] and gerbils[16] can be infested also, diagnosis can be made by examining their feathers or fur for mites and is best carried out by a veterinary professional.

Treatment

Treatment of gamasoidosis can be difficult; avian mites have developed resistance to multiple pesticides and the different species concerned display varied ecologies that necessitate divergent treatment approaches.[21]

For a patient to achieve full recovery, the mites must be eradicated from the person's environment through the removal of nests and appropriate disinfestation of infested areas by a pest control professional.[15] Total eradication can be difficult to achieve as D. gallinae can survive for longer than nine months without a blood meal[36][37] and is capable of both digesting[38] and completing its life cycle on human blood alone.[19] Additionally, populations can expand rapidly, with a single female capable of laying up to "30 eggs in their lifetime";[39] prolonged darkness has been found to significantly promote mite population growth.[40]

Patients are advised to:[3][14]

- Shower frequently to remove mites from their skin and hair.

- Washing clothes and bedding at temperatures, at or above 60 °C.

- Remove the source of the mites, such as infested animal shelters, cages and nests.

- Perform regular intensive vacuum cleaning and steam cleaning — the vacuum bag should be placed in a sealed bag and thrown away outside in a contained bin.

- Disinfect infested household items and areas with effective acaricides such as pyrethroids.

- Washing of textiles or steam cleaning (cushions, carpets, curtains) at or above 60 °C, and drying them using an automated laundry drier.

- Dust infested areas with amorphous silica gels[41] such as CimeXa.[42]

- Heat treat their residence — raising the temperature of their living space above 55 °C for a sustained period.

- Reduce the relative humidity of their home below 55%.[36]

Fluralaner, an effective acaricide, available commercially as Bravecto[43] may be administered to cats and dogs after consulting a vet.

Antihistamines and topical corticosteroids can be used for temporary relief of symptoms.[44]

Certain essential oils are known to have an acaricide effect on avian mites.[45] Cardboard traps impregnated with neem extracts or other acaricides[46] can be used to reduce avian mite populations.[47]

In the case of scalp infestation, treatments with 1% permethrin shampoo can be used to remove the mites.[27] For ear canal infestation, aural toilet is recommended with a course of 1% permethrin to be used as ear drops and for infected wax to be removed by a professional.[18]

Ineffective and often prolonged attempts to eradicate infestations commonly result in economic issues, due to a significant financial outlay when patients relocate or attempt to control these infestations.[21]

Epidemiology

D. gallinae poses a significant threat to public health as the mite may be a vector/reservoir of several zoonotic pathogens,[24] such as Chlamydia psittaci, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, Salmonella spp., Lyme disease,[24] Mycobacterium spp., Coxiella burnetii, Bartonella spp.,[26] Borrelia burgdorferi,[48] Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Eastern equine encephalitis virus, and Fowlpox virus.[49]

References

- Kowalska M, Kupis B (1976). "Gamasoidosis (gamasidiosis)-not infrequent skin reactions, frequently unrecognized". Polish Medical Sciences and History Bulletin. 15–16 (4): 391–4. PMID 826895.

- Wambier CG, Wambier SP (2012). "Gamasoidosis illustrated--from the nest to dermoscopy". Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 87 (6): 926–7. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962012000600021. PMC 3699918. PMID 23197219.

- Cafiero MA, Barlaam A, Camarda A, Radeski M, Mul M, Sparagano O, Giangaspero A (September 2019). "Dermanysuss gallinae attacks humans. Mind the gap!". Avian Pathology. 48 (sup1): S22–S34. doi:10.1080/03079457.2019.1633010. PMID 31264450.

- Sulzberger MB (1936-01-01). "Avian Itch Mites as a Cause of Human Dermatoses". Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology. 33 (1): 60. doi:10.1001/archderm.1936.01470070063006.

- Sparagano OA, George DR, Harrington DW, Giangaspero A (2014). "Significance and control of the poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae". Annual Review of Entomology. 59: 447–66. doi:10.1146/annurev-ento-011613-162101. PMID 24397522.

- Sigognault Flochlay A, Thomas E, Sparagano O (August 2017). "Poultry red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) infestation: a broad impact parasitological disease that still remains a significant challenge for the egg-laying industry in Europe". Parasites & Vectors. 10 (1): 357. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2292-4. PMC 5537931. PMID 28760144.

- James WD, Timothy G B, et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-7216-2921-6.

- Orton DI, Warren LJ, Wilkinson JD (March 2000). "Avian mite dermatitis". Clinical and Experimental Dermatology. 25 (2): 129–31. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00594.x. PMID 10733637.

- Mentz MB, Silva GL, Silva CE (2015). "Dermatitis caused by the tropical fowl mite Ornithonyssus bursa (Berlese) (Acari: Macronyssidae): a case report in humans". Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 48 (6): 786–8. doi:10.1590/0037-8682-0170-2015. PMID 26676510.

- Cafiero MA, Raele DA, Mancini G, Galante D (July 2016). "Dermatitis by Tropical Rat Mite, Ornithonyssus bacoti (Mesostigmata, Macronyssidae) in Italian city-dwellers: a diagnostic challenge". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 30 (7): 1231–3. doi:10.1111/jdv.13162. PMID 25912467.

- Hetherington GW, Holder WR, Smith EB (March 1971). "Rat mite dermatitis". JAMA. 215 (9): 1499–500. doi:10.1001/jama.1971.03180220079019. PMID 5107633.

- Watson J (2008-01-01). "New building, old parasite: Mesostigmatid mites--an ever-present threat to barrier facilities". ILAR Journal. 49 (3): 303–9. doi:10.1093/ilar.49.3.303. PMC 7108606. PMID 18506063.

- Alexander JO (1984). "Infestation with Gamasid Mites". Arthropods and Human Skin. Springer, London. pp. 303–315. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-1356-0_17. ISBN 9781447113584.

- Cafiero MA, Galante D, Raele DA, Nardella MC, Piccirilli E (2017). "Outbreaks of Dermanyssus gallinae (Acari, Mesostigmata) Related Dermatitis in Humans in Public and Private Residences. Italy (2001-2017): An Expanding Skin Affliction". J Clin Case Rep. 7 (1035): 2.

- Cafiero MA, Camarda A, Galante D, Mancini G, Circella E, Cavaliere N, Santagada G, Caiazzo M, Lomuto M (2013). "Outbreaks of red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) dermatitis in city-dwellers: an emerging urban epizoonosis". Hypothesis in Clinical Medicine: 413–24.

- Lucky AW, Sayers C, Argus JD, Lucky A (February 2001). "Avian mite bites acquired from a new source--pet gerbils: report of 2 cases and review of the literature". Archives of Dermatology. 137 (2): 167–70. PMID 11176688.

- Kong TK, To WK (April 2006). "Images in clinical medicine. Bird-mite infestation". The New England Journal of Medicine. 354 (16): 1728. doi:10.1056/nejmicm050608. PMID 16625011.

- Rossiter A (April 1997). "Occupational otitis externa in chicken catchers". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 111 (4): 366–7. doi:10.1017/s0022215100137338. PMID 9176622.

- Pampiglione S, Pampiglione G, Pagani M, Rivasi F (September 2001). "[Persistent scalp infestation by Dermanyssus gallinae in an Emilian country-woman]". Parassitologia. 43 (3): 113–5. PMID 11921537.

- Ahmed N, El-Kady A, Abd Elmaged W, Almatary A (2018-08-01). "Dermanyssus gallinae (Acari: Dermanyssidae) a cause of recurrent papular urticaria diagnosed by light and electron microscopy". Parasitologists United Journal. 11 (2): 112–118. doi:10.21608/PUJ.2018.16320. ISSN 1687-7942.

- Sparagano O, Finn R, Mul M, Giangaspero A, Cafiero MA, Willingham N, Lyons K, Lovers A, George D (2017). "The emergence of Dermanyssus gallinae as an arthropod pest in urban context and the "one Health" approach". Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Urban Pests: 203–208.

- "Pruritic Dermatitis Caused by Bird Mite Infestation". Cutis. 97 (1). 2016-01-01.

- Nordenfors H, Chirico J (December 2001). "Evaluation of a sampling trap for Dermanyssus gallinae (Acari: Dermanyssidae)". Journal of Economic Entomology. 94 (6): 1617–21. doi:10.1603/0022-0493-94.6.1617. PMID 11777073.

- George DR, Finn RD, Graham KM, Mul MF, Maurer V, Moro CV, Sparagano OA (March 2015). "Should the poultry red mite Dermanyssus gallinae be of wider concern for veterinary and medical science?". Parasites & Vectors. 8: 178. doi:10.1186/s13071-015-0768-7. PMC 4377040. PMID 25884317.

- Regan AM, Metersky ML, Craven DE (December 1987). "Nosocomial dermatitis and pruritus caused by pigeon mite infestation". Archives of Internal Medicine. 147 (12): 2185–7. doi:10.1001/archinte.1987.00370120121021. PMID 3689070.

- Cafiero MA, Viviano E, Lomuto M, Raele DA, Galante D, Castelli E (July 2018). "Dermatitis due to Mesostigmatic mites (Dermanyssus gallinae, Ornithonyssus [O.] bacoti, O. bursa, O. sylviarum) in residential settings". Journal of the German Society of Dermatology. 16 (7): 904–906. doi:10.1111/ddg.13565. PMID 29933524.

- Pezzi M, Leis M, Chicca M, Roy L (October 2017). "Gamasoidosis caused by the special lineage L1 of Dermanyssus gallinae (Acarina: Dermanyssidae): A case of heavy infestation in a public place in Italy". Parasitology International. 66 (5): 666–670. doi:10.1016/j.parint.2017.05.001. PMID 28483708.

- Bardach H (January 1981). "[Acariasis due to dermanyssus gallinae (gamosoidosis) in Vienna (author's transl)]". Zeitschrift für Hautkrankheiten. 56 (1): 21–6. PMID 7222880.

- Powlesland R (1978-06-01). "Behaviour of the haematophagous mite Ornithonyssus bursa in starling nest boxes in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Zoology. 5 (2): 395–399. doi:10.1080/03014223.1978.10428325.

- Williams RW (November 1958). "An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (Degeer, 1778) (Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York City resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 7 (6): 627–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.627. PMID 13595207.

- Kilpinen O, Mullens BA (December 2004). "Effect of food deprivation on response of the mite, Dermanyssus gallinae, to heat". Medical and Veterinary Entomology. 18 (4): 368–71. doi:10.1111/j.0269-283X.2004.00522.x. PMID 15642003.

- Kilpinen O (2005). "How to obtain a bloodmeal without being eaten by a host: the case of poultry red mite, Dermanyssus gallinae". Physiological Entomology. 30 (3): 232–240. doi:10.1111/j.1365-3032.2005.00452.x. ISSN 0307-6962.

- Dukas R (2008). "Evolutionary biology of insect learning". Annual Review of Entomology. 53 (1): 145–60. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.53.103106.093343. PMID 17803459. S2CID 18299890.

- Di Palma A, Leone F, Albanese F, Beccati M (April 2018). "A case report of Dermanyssus gallinae infestation in three cats". Veterinary Dermatology. 29 (4): 348–e124. doi:10.1111/vde.12547. PMID 29708634.

- Ramsay GW, Mason PC, Hunter AC (July 1975). "Letter: Chicken mite (Dermanyssus gallines) infesting a dog". New Zealand Veterinary Journal. 23 (7): 155–6. doi:10.1080/00480169.1975.34225. PMID 1058385.

- Nordenfors H, Höglund J, Uggla A (January 1999). "Effects of temperature and humidity on oviposition, molting, and longevity of Dermanyssus gallinae (Acari: Dermanyssidae)". Journal of Medical Entomology. 36 (1): 68–72. doi:10.1093/jmedent/36.1.68. PMID 10071495. S2CID 14208397.

- Kirkwood A (1963-12-01). "Longevity of the mites Dermanyssus gallinae and Liponyssus sylviarum". Experimental Parasitology. 14 (3): 358–366. doi:10.1016/0014-4894(63)90043-2. ISSN 0014-4894. PMID 14099848.

- Williams RW (November 1958). "An infestation of a human habitation by Dermanyssus gallinae (Degeer, 1778) (Acarina: Dermanyssidae) in New York City resulting in sanguisugent attacks upon the occupants". The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 7 (6): 627–9. doi:10.4269/ajtmh.1958.7.627. PMID 13595207.

- Chauve C (November 1998). "The poultry red mite Dermanyssus gallinae (De Geer, 1778): current situation and future prospects for control". Veterinary Parasitology. 79 (3): 239–45. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(98)00167-8. PMID 9823064.

- Wang C, Ma Y, Huang Y, Su S, Wang L, Sun Y, et al. (May 2019). "Darkness increases the population growth rate of the poultry red mite Dermanyssus gallinae". Parasites & Vectors. 12 (1): 213. doi:10.1186/s13071-019-3456-1. PMC 6505187. PMID 31064400.

- Schulz J, Berk J, Suhl J, Schrader L, Kaufhold S, Mewis I, et al. (September 2014). "Characterization, mode of action, and efficacy of twelve silica-based acaricides against poultry red mite (Dermanyssus gallinae) in vitro". Parasitology Research. 113 (9): 3167–75. doi:10.1007/s00436-014-3978-6. PMID 24908434.

- "Does Cimexa kill mites as well?". www.domyown.com. Retrieved 2019-09-29.

- Brauneis MD, Zoller H, Williams H, Zschiesche E, Heckeroth AR (December 2017). "The acaricidal speed of kill of orally administered fluralaner against poultry red mites (Dermanyssus gallinae) on laying hens and its impact on mite reproduction". Parasites & Vectors. 10 (1): 594. doi:10.1186/s13071-017-2534-5. PMC 5712167. PMID 29197422.

- Dogramaci AC, Culha G, Ozçelik S (September 2010). "Dermanyssus gallinae infestation: an unusual cause of scalp pruritus treated with permethrin shampoo". The Journal of Dermatological Treatment. 21 (5): 319–21. doi:10.3109/09546630903287437. PMID 20687864.

- Kim SI, Yi JH, Tak JH, Ahn YJ (April 2004). "Acaricidal activity of plant essential oils against Dermanyssus gallinae (Acari: Dermanyssidae)". Veterinary Parasitology. 120 (4): 297–304. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.12.016. PMID 15063940.

- Chirico J, Tauson R (December 2002). "Traps containing acaricides for the control of Dermanyssus gallinae". Veterinary Parasitology. 110 (1–2): 109–16. doi:10.1016/S0304-4017(02)00310-2. PMID 12446095.

- Lundh J, Wiktelius D, Chirico J (June 2005). "Azadirachtin-impregnated traps for the control of Dermanyssus gallinae". Veterinary Parasitology. 130 (3–4): 337–42. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.02.012. PMID 15890446.

- Raele DA, Galante D, Pugliese N, La Salandra G, Lomuto M, Cafiero MA (May 2018). "Mesostigmata, Acari), related to urban outbreaks of dermatitis in Italy". New Microbes and New Infections. 23: 103–109. doi:10.1016/j.nmni.2018.01.004. PMC 5913367. PMID 29692913.

- Cafiero MA, Camarda A, Circella E, Santagada G, Schino G, Lomuto M (November 2008). "Pseudoscabies caused by Dermanyssus gallinae in Italian city dwellers: a new setting for an old dermatitis". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 22 (11): 1382–3. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02645.x. PMID 18384564.