Geography of Pennsylvania

The geography of Pennsylvania varies from sea level marine estuary to mountainous plateau. It's significant for its natural resources and ports, and is notable for its role in the history of the United States.

Major features

Pennsylvania's nickname, the Keystone State, derives from the fact that the state forms a geographic bridge both between the Northeastern states and the Southern states, and between the Atlantic seaboard and the Midwest. Also, the title of "Keystone" is for the importance of Pennsylvania to the entire U.S. It even has a toehold on the Great Lakes, with the Erie triangle. It is bordered on the north and northeast by New York; on the east by New Jersey; on the south by Delaware, Maryland, and West Virginia; on the west by Ohio; and on the northwest by Lake Erie. It has a small border on Lake Erie with Canada. The Delaware, Susquehanna, Monongahela, Allegheny, and Ohio rivers are the major rivers of the state. The Lehigh River, the Toughener River and Oil Creek are smaller rivers which have played an important role in the development of the state. It is one of the thirteen U.S. states that share a border with Canada.

Pennsylvania is 180 miles (290 km) north to south and 310 miles (500 km) east to west. The total land area is 44,817 square miles (116,080 km2)—739,200 acres (2,991 km2) of which are bodies of water. It is the 33rd largest state in the United States. The highest point of 3,213 feet (979 m) above sea level is at Mount Davis. Its lowest point is at sea level on the Delaware River.

The Pennsylvania Dutch region

The Pennsylvania Dutch region in south-central Pennsylvania is a favorite for sightseers. The Pennsylvania Dutch, including the Old Order Amish, the Old Order Mennonites and at least 15 other sects, are common in the rural areas around the cities of Lancaster, York, and Harrisburg, with smaller numbers extending northeast to the Lehigh Valley and up the Susquehanna River valley. (There are actually more Old Order Amish in Holmes County, Ohio, and there are plain sect communities in at least 47 states, but many Mennonites remain, particularly in Lancaster County.) Some adherents eschew modern conveniences and use horse-drawn farming equipment and carriages, while others are virtually indistinguishable from non-Amish or Mennonites. Descendants of the plain sect immigrants who do not practice the faith may refer to themselves as Pennsylvania Germans.

Despite the name, the people are not from the Netherlands, but rather are from various parts of southwest Germany, Alsace and Switzerland. The word "Dutch" here is left over from the original meaning of the English word "Dutch" which once referred to the entire West Germanic dialect continuum.[1]

Western Pennsylvania

The western third of the state can be considered a separate large geophysical unit, distinctive enough that it may best be described on its own. Several important, complex factors set Western Pennsylvania apart in many respects from the east, such as the initial difficulty of access across the mountains, rivers oriented to the Mississippi River drainage system, and above all, the complex economics involved in the rise and decline of the American steel industry centered on Pittsburgh. Other factors, such as a markedly different style of agriculture, the rise of the oil industry, timber exploitation and the old wood chemical industry, and even, in linguistics, the local dialect, all make this large area sometimes seem a virtual "state within a state".

The mountains

Pennsylvania is bisected in an S-curve (or roughly diagonally) by the barrier ridges of the Appalachian Mountains from southwest to northeast, forcing pretwentieth century ground travel most often on or near the ancient Amerindian trails along the higher terrains of the local watersheds with limited penetration and connectivity often only through water gaps. As rough looking as the first map appears, the valley bottoms throughout the entire central part of the state and parts of lower New York state are connected by the Susquehanna River and its tributaries—virtually the whole length of which was improved into the Pennsylvania Canal System in the 1830s. To the northwest of the folded mountains is the Allegheny Plateau which lies above the cliff-like Allegheny Front escarpment, which continues into southwestern and south central New York, and is pierced in only a few places known as the gaps of the Allegheny.

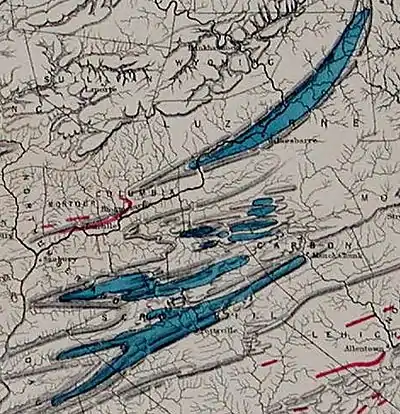

This Allegheny Plateau is so dissected by valleys formed by small streams and springs that it also seems mountainous, but with elevation differences between valley floors and hilltop peaks most often less than a few hundred feet. The plateau is underlain by sedimentary rocks of Mississippian and Pennsylvanian age, which bear abundant fossils, mineral deposits such as iron, as well as natural gas, coal and petroleum. These regions fostered 17th-19th century industries locally even into the 1930s days of mass production. To the south and east of the escarpment/plateau region, the folded mountains and alternating valleys are known as the Ridge-and-Valley Appalachians. These extend from the South of the Appalachians to northern New England save where cut by water gaps. In Northeastern Pennsylvania from the east of Harrisburg on the Susquehanna River, these ridge and valley features contain the richest and most widespread deposits of high energy clean burning anthracite coal in the world—the Coal Region—without which the industrial revolution in the United States would have been severely retarded and delayed.

In 1859, near Titusville, Edwin L. Drake drilled the first oil well in the U.S. into these sediments.[2] Similar rock layers also contain coal to the south and east of the oil and gas deposits. In the metamorphic (folded) belt, anthracite (hard coal) is mined near Wilkes-Barre and Hazelton. These fossil fuels have been an important resource to Pennsylvania. Timber and dairy farming are also sources of livelihood for midstate and western Pennsylvania. Along the shore of Lake Erie in the far northwest are orchards and vineyards.

During the most recent Ice Age, the northeastern and northwestern corners of present-day Pennsylvania were buried under the southern fringes of the Laurentide Ice Sheet. Glaciers extended into the Appalachian valleys of central Pennsylvania, but the ice did not over top the mountains. At its furthest extent it spread as far south as Moraine State Park, about 40 miles (64 km) north of Pittsburgh.

The shores

Pennsylvania has 57 miles (92 km) of shoreline along the Delaware River estuary, including the busy Port of Philadelphia, one of the largest seaports in the U.S..[3] Chester, downstream, is a smaller but still important port. The tidal marsh of Pennsylvania's only saltwater shore has been protected as John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge at Tinicum.

Pennsylvania also has a narrow inland freshwater shore at Erie, the Great Lakes outlet on Lake Erie in the Erie Triangle.

In the west the Port of Pittsburgh is also very large and even exceeds Philadelphia in rank by annual tonnage, because of the large volume of bulk coal shipped by barge down the Ohio River.

Ecological disasters

Pennsylvania has been the site of some of the worst ecological disasters experienced in U.S. history:

- In 1889, the South Fork Dam, impounding a recreational mountain lake for sportsmen, burst after a heavy rain and destroyed the downstream factory town of Johnstown, killing over 2,200 inhabitants in the notorious Johnstown Flood (the town was later rebuilt and is a reasonably large community today in the central mountains).

- In 1948, an air inversion over Donora trapped pollution from nearby metal processing plants, killing 20 and causing health complications for many more.

- In 1961, an exposed seam of coal at Centralia caught fire and eventually forced almost the entire community to abandon the area; the underground coal fire is still burning today and it is estimated that it can burn for another 250 years.

- In 1979, the Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Incident near the state capital of Harrisburg, while not as destructive to the community, nevertheless cost close to $1 billion to clean up and changed the national public perception of nuclear power to a much less favorable viewpoint.

Climate

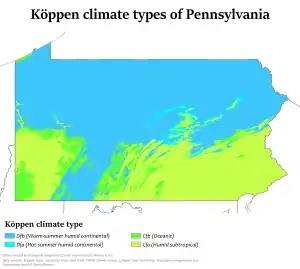

Pennsylvania has three general climate regions, which are determined by altitude more than latitude or distance from the oceans. Most of the state falls in the humid continental climate zone. The lower elevations, including most of the major cities, has a moderate continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfa), with cool to cold winters and hot, humid summers. Highland areas have a more severe continental climate (Köppen Dfb) with warm, humid summers and cold, more severe and snowy winters. Extreme southeastern Pennsylvania, around Philadelphia borders into a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa), with milder winters and hot, humid summers.

Precipitation is abundant throughout the state, as the primary climatic influences are the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico, plus Arctic influences that cross over the Great Lakes.