Glycidamide

Glycidamide is part of the chemical group of amides and oxiranes, it is classified as a carcinogenic substance.[1] It is associated with tobacco either as natural component, pyrolysis product in tobacco smoke or additive for one or more types of tobacco products. Glycidamide is formed from acrylamide. Acrylamide is an industrial chemical which is used in several ways, such as production of polyacrylamides for (waste)water treatment, textile, paper processing and cosmetics. It is also a product formed in certain foods prepared at high temperature frying, baking or roasting, such as fried potatoes, bakery products and coffee. Glycidamide is formed through the reaction of unsaturated fatty acids with oxygen. It is a dangerous substance, since it causes small mutations in cells which can result in several forms of cancer.

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Oxirane-2-carboxamide | |

| Other names

Glycidic acid amide Oxiranecarboxamide | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.024.694 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C3H5NO2 | |

| Molar mass | 87.078 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.39 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 32–34 °C (90–93 °F; 305–307 K) |

| Pharmacology | |

| Pharmacokinetics: | |

| 5 hours | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

History

Two of the first researchers who acknowledged the existence of glycidamide were Murray and Cloke in 1934.[2] They performed experiments on glycidamide formation (see Synthesis for more details).

Since glycidamide is a metabolite of acrylamide, not much studies has been done on glycidamide on its own. Most of the studies focus on the effects of acrylamide, whereas less studies focus specifically on the effects of glycidamide. There are many studies that combine acrylamide and glycidamide, but the focus is still mainly on acrylamide.

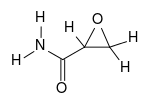

Structure and reactivity

Glycidamide is a reactive epoxide metabolite from acrylamide.[3] Glycidamides are fine crystals with lumps with a light orange color. It has an asymmetrical structure with electrophilic properties[4] and can react with nucleophiles. This results in covalent binding of the electrophile.[5] There is no data on the odor of glycidamide.

Glycidamide gives a positive response in the Ames/Salmonella mutagenicity assay, which indicates that it can cause mutations in the DNA.[3]

Synthesis

Glycidamide is naturally formed by oxidation of acrylamide by cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1). This reaction follows Michaelis-Menten kinetics.[6] Due to this reaction, glycidamide becomes critical to the genotoxicity of acrylamide.[4][7] Saturated fatty acids protect the acrylamide from forming glycidamide. When during food processing, oil is used that contains unsaturated fatty acids, the amount of glycidamide formed is much higher.[8]

The first experiments on glycidamide formation were done by Murray and Cloke (1934).[2] They tried to form glycidamides from α,β-ethylenic nitriles. In order to do so, they used the modified Radziszewski reaction. The Radziszewski reaction refers to a method for the preparation of amides, described by Radziszewski in 1885. The amides are prepared “by the action of 3% hydrogen peroxide on nitriles in the presence of alkali and at a temperature of 40 degrees Celsius”.[2] The reaction was modified by adding methanol, ethanol and acetone. Some nitriles did indeed give glycidamides.

Reactions

Glycidamide reacts with DNA to form DNA adducts and is more reactive to DNA than acrylamide. Several glycidamide-DNA adducts have been characterized (Beland, 2015). The main DNA adducts are N7-(2-carbamoyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-guanine (or N7-GA-Gua) and N3-(2-carbamoyl-2-hydroxyethyl)adenine (or N3-GA-Ade).[9] Glycidamide also reacts with haemoglobine (Hb) to form a cysteine adduct, S-(20hydroxy-2carboxyethyl)cysteine.[5] With this reaction, N-terminal valine adducts are also formed.[10]

Available forms (isoforms)

There are two isomers of this connection: (R)-Glycidamide and the mirror image (S)-Glycidamide. The racemate (RS)-Glycidamide is a 1:1 mixture of both isomers.

Mechanism of action

Epoxide

The epoxide is a strong alkylating agent, which can open a ring to form a reactive ion. This reactive ion can bind to DNA and alkylate it. Alkylation of DNA forms DNA adducts and can cause mutagenicity.[11] There are often tumors observed at the site of exposure.

Neurotoxicity

Inhibition of the sodium/potassium ATPase protein present in the plasma membrane of the nerve cell is caused by glycidamide.[12] Intracellular sodium increases and intracellular potassium decreases due to this inhibition. This causes depolarization of the nerve membrane. The depolarization triggers a reverse sodium/calcium exchange, which will cause calcium-mediated axon degeneration.[13]

Metabolism

The liver is a very active organ in the metabolism of xenobiotics. Substances in the liver modify the compounds to make them more soluble in water, in order to excrete them through bile and urine. This modification, however, can result in a greater toxicity of the compound.[14] Whether this is the case for glycidamide remains unclear.

Glycidamide can be detoxified through different pathways to glycidamide-glutathione conjugates. There is an enzymatic pathway via glutathione-S-transferase and a non-enzymatic pathway. These glycidamide-glutathione conjugates are further metabolized to mercapturic acids by different peptidases and transferases, such as gamma-glutamyl-transpeptidase, dipeptidase and N-acetyltransferase. The mercapturic acids that can be formed are N-acetyl-S-(2-carbamoylethyl)-cysteine (AAMA), N-acetyl-S-(1-carbamoyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-cysteine (GAMA2), and N-acetyl-S-(2-carbamoyl-2-hydroxyethyl)-cysteine (GAMA3) (Huang et al., 2011). These mercapturic acids are excreted through urine.[7]

Glycidamide can also be hydrolyzed to glyceramide both spontaneously or enzymatically by microsomal epoxide hydrolase.[7] This too can be excreted through urine.[5]

Toxicity

The DEREK NEXUS assessment shows that it is plausible (meaning that there is weight of evidence in favor of this proposition) that glycidamide is carcinogenic, mutagenic, neurotoxic, developmental toxic and oestrogenic. It also shows that it is plausible that glycidamide causes chromosome damage and irritation of the eye and skin. The results of this assessments are confirmed by the Hazard Identification of lookchem. It states that glycidamide may cause cancer and heritable genetic damage. It also causes skin and eye irritation.

Animal studies

Mice and rats are used for most of the studies of glycidamide. These are used, because the formation of glycidamide adducts is directly proportional in man and rat.[5]

Studies with Big Blue mice and rats have shown mutations and DNA adducts that are consistent with those arising from glycidamide.[6][15][16] Besaratinia and Pfeifer (2004) for instance, found cytotoxic effects in Big Blue mouse embryonic fibroblasts after being exposed to increasing concentrations of glycidamide. Another study found tumors in the mice bodies after treatment with glycidamide.[9]

A study by National Toxicology Program (2014)[17] provided evidence of carcinogenic activity of glycidamide in several species of rats and mice. For two years, rats and mice were exposed to varying doses of glycidamide in drinking water. In the rats and mice were several carcinogenic effects found, such as carcinomas, fibroadenomas and malignant mesotheliomas.

References

- "Glycidamide M930003 - NTP". ntp.niehs.nih.gov. Retrieved 2016-03-13.

- Murray, J. V., & Cloke, J. B. (1934). The Formation of Glycidamides by the Action of Hydrogen Peroxide on α, β-Ethylenic Nitriles1. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 56(12), 2749-2751.

- Bergmark, E., Calleman, C. J., & Costa, L. G. (1991). Formation of hemoglobin adducts of acrylamide and its epoxide metabolite glycidamide in the rat. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 111(2), 352-363.

- Beland, F. A., Olson, G. R., Mendoza, M. C., Marques, M. M., & Doerge, D. R. (2015). Carcinogenicity of glycidamide in B6C3F 1 mice and F344/N rats from a two-year drinking water exposure. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 86, 104-115.

- IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. "Acrylamide" in IARC Monographs on the evaluation of carcinogen risk to humans, International Agency for Research on Cancer, Lyon, France, 1994, 60:389–433.

- Besaratinia, A., & Pfeifer, G. P. (2004). Genotoxicity of acrylamide and glycidamide. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 96(13), 1023-1029.

- Luo, Y. S., Long, T. Y., Shen, L. C., Huang, S. L., Chiang, S. Y., & Wu, K. Y. (2015). Synthesis, characterization and analysis of the acrylamide-and glycidamide-glutathione conjugates. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 237, 38-46.

- Granvogl, M., Koehler, P., Latzer, L., & Schieberle, P. (2008). Development of a stable isotope dilution assay for the quantitation of glycidamide and its application to foods and model systems. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry, 56(15), 6087-6092.

- Von Tungeln, L. S., Doerge, D. R., Gamboa da Costa, G., Matilde Marques, M., Witt, W. M., Koturbash, I., Pogribny, I.P. & Beland, F. A. (2012). Tumorigenicity of acrylamide and its metabolite glycidamide in the neonatal mouse bioassay.International Journal of Cancer, 131(9), 2008-2015.

- Schettgen, T., Müller, J., Fromme, H., & Angerer, J. (2010). Simultaneous quantification of haemoglobin adducts of ethylene oxide, propylene oxide, acrylonitrile, acrylamide and glycidamide in human blood by isotope-dilution GC/NCI-MS/MS. Journal of Chromatography B 878(27), 2467-2473.

- Sugiura, K., & Goto, M. (1981). Mutagenicities of styrene oxide derivatives on bacterial test systems: relationship between mutagenic potencies and chemical reactivity. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 35(1), 71-91.

- Lehning, E. J., Persaud, A., Dyer, K. R., Jortner, B. S., & LoPachin, R. M. (1998). Biochemical and morphologic characterization of acrylamide peripheral neuropathy. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 151(2), 211-221.

- LoPachin, R. M., & Lehning, E. J. (1997). Mechanism of calcium entry during axon injury and degeneration. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 143(2), 233-244.

- Kurebayashi, H., & Ohno, Y. (2006). Metabolism of acrylamide to glycidamide and their cytotoxicity in isolated rat hepatocytes: protective effects of GSH precursors. Archives of toxicology, 80(12), 820-828.

- Manjanatha, M.G., Aidoo, A., Shelton, S.D., Bishop, M.E., McDaniel, L.P., Lyn-Cook, L.E. & Doerge D.R. (2006). Genotoxicity of acrylamide and its metabolite glycidamide administered in drinking water to male and female Big Blue mice. Environ Mol Mutagen;47:6–17

- Mei, N., McDaniel, L.P., Dobrovolsky, V.N., Guo, X., Shaddock, J.G., Mittelstaedt, R.A., Azuma, M., Shelton, S.D., McGarrity, L.J., Doerge, D.R. & Heflich, R.H. (2010). The genotoxicity of acrylamide and glycidamide in Big Blue rats. Toxicol Sci; 115:412–21

- National Toxicology Program. (2014). NTP Technical Report on the Toxicology and Carcinogenesis: Studies of Glycidamide. Retrieved on March 11, 2016, from http://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/ntp/htdocs/lt_rpts/tr588_508.pdf