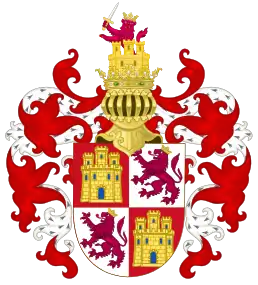

Heraldry of Castile

The coat of arms of Castile was the heraldic emblem of its monarchs. Historian Michel Pastoureau says that the original purpose of heraldic emblems and seals was to facilitate the exercise of power and the identification of the ruler, due to they offered for achieving these aims. These symbols were associated with the kingdom, and eventually also represented the intangible nature of the national sentiment or sense of belonging to a territory.[1]

The blazon of the arms of Castile is:

Gules a triple-towered castle Or masoned Sable and ajoure Azure.[2]

Origin

The Royal Arms of Castile first adopted at the start of the age of heraldry (circa 1175),[1] that spread across Europe during the next century.[3] The Spanish heraldist Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués explained that there is no evidence that there was a consolidated Castilian emblem before the reign of King Alfonso VIII or these arms had pre-heraldic history as the heraldry of León.

The chancery of Alfonso VIII adopted a Signum Regis (seal) in 1165. This device had wheel shape, a defining characteristic of the chancery of monarchs of Castile since 1157. This author has pointed out that the emergence of the castle device Castile was similarly to the Leonese lion but at a much more accelerated pace. One of the earliest known testimonies that document the origin of the castle emblem was carried out by bishop Lucas de Tuy. In Castile, as it was common at that time, the first examples of the castle as heraldic symbols have been found at the reverse of pendent seals. The Signum Regis of King Alfonso VIII not always shown a castle. This monarch initially used a seal with a cross with pole. By the year 1163 was used a single side with an equestrian image of Alfonso VIII holding a lance without a standard, this element would have allowed us to determine the royal device used at that time. Following seals continued depicting equestrian images as central motif. The castle appeared for first time on the reverse of pendent seals. The first preserved seal impression with the castle dates from 1176, contained in a document located in the Toledo Cathedral. The matrix of this seal dates back before 1171 due to its typology. According Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués it is likelythat the device of the castle was adopted in 1169, when Alfonso VIII came of age at fourteen. As a clear example of canting arms, the castle was adopted with a clear territorial connotation. This decision could be motivated by a desire to claim the sovereignty of the Castilian monarch against the Kingdom of León.

Since from its inception the castle has retained a basic design - three towers, higher the central than lateral ones - leads to the conclusion that it is a native creation, different from the existing in Central Europe.

Concerning the colours of the arms (tincture according to heraldry), it has been found that the combination «Or on a Gules field», was already fixed at least since the reign of King Ferdinand III, called the Saint. This selection could be determined by the Heraldry of the consort of the King Alfonso VIII, Queen Eleanor of England, daughter of Henry II, King of England. The arms used by the Queen were the Royal Arms of England, three identical gold lions (also known as leopards) with blue tongues and claws, walking past but facing the observer, arranged in a column on a red background. Although the tincture azure of tongue and claws is not cited in many blazons, they are historically a distinguishing feature of the Arms of England. These arms, which are one of the oldest heraldic emblems, have had much success at that time due to the ease which offered be easily recognisable at distance.

This hypothesis is reinforced by the fact that the marriage of Alfonso VIII and Eleanor was celebrated from 1170 to 1176, dates immediately prior to the adoption of the emblem according preserved sources. Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués defends as another possible reason for the choice of this combination of colors, for appearing more frequently in the arms. The selection of the third colour, shown in the door and windows, Azure (blue) could be due to the contrast with the other two, offering or that it was the third most commonly used colour after the previous.

In the Reign of Alfonso VIII was usual that the castle emblem was presented as device and not in an escutcheon. We can be seen this device on the tomb of Alfonso VIII and Queen Eleanor, in the Abbey of Santa María la Real de Las Huelgas (Burgos). The grave is decorated with the device of the castle and the English arms shown in a shield. The Castle, as a device and not as part of an escutcheon, appears in all Castilian coins of the time. Castle devices placed in row have been found on two stoles embroidered by Queen Eleanor from 1197 to 1198. One of the first representations of the castle emblem in an escutcheon has been displayed on a green brocade removed from the tomb of King Alfonso VIII.

Propagation

France

Arms of Robert I, Count of Artois

Arms of Robert I, Count of Artois Arms of Alphonse, Count of Poitiers

Arms of Alphonse, Count of Poitiers Arms of Charles I of Anjou

Arms of Charles I of Anjou

(until 1246)

Arms of Alphonso of Brienne

Arms of Alphonso of Brienne

Portugal

Arms of Beatrice of Portugal

Arms of Beatrice of Portugal

(As disputed Queen of Portugal)

Alfonso VIII's male issue did not survive him. Despite this, the Royal Arms of Castile was spread though female lineage into royal insignia used in Portugal, Aragon and France.

The Castilian arms were present in the heraldry of all the grandchildren of Alfonso VIII, except Kings Louis IX of France and Sancho II of Portugal that, as reigning monarchs, used their respective "arms of dominion". Castles Or on field Gules were included on the shields of the children of Louis VIII of France and Queen Blanche, also depicted on the tomb of other maternal grandson of Alfonso VIII, Infante Alfonso of Aragon (1222-1260), the eldest son of James I of Aragon and Queen Eleanor, decorated with the four paletts Gules and differenced with a bordure charged with twenty escutcheons Gules with castles. But one of the most prominent example occurred in Portugal, when Afonso III added a bordure Gules charged with castles to the royal arms and remaining these until 1910, when the country became a republic. Since 1911 the bordure with castles have continued as part of the national coat of arms of Portugal. A variant of the arms is adopted by Ceuta since its beginning of Portuguese rule, even though it was later handed over to Spain.

Quartering with the arms of León

.svg.png.webp) 1230-1284

1230-1284.svg.png.webp) 1281-1383

1281-1383.svg.png.webp) 1383-1390

1383-1390.svg.png.webp) 1390-1406

1390-1406.svg.png.webp) ca.1400-ca.1500

ca.1400-ca.1500.svg.png.webp) ca.1500-1715

ca.1500-1715

When his father, Alfonso IX, died in 1230, King Ferdinand III of Castile received the Kingdom of León and united the two kingdoms. The King wanted to symbolize the union for the first time, quartering the Castilian and Leonese arms, giving the arms of Castile pride of place. His aim was to have a device that reflects an indivisible union of kingdoms due to of the transitory symbolism of the impalement and secondary of the bordure. This method, very widespread spread in the Heraldry of different countries, was soon followed successfully throughout Europe. In the middle of the 12th century quarterings were used by monarchs of Aragon-Sicily, Brabant and others like the Kings of England, Navarre or Bohemia adopted it during the next century. John I of Castile impaled the Castilian quartering with the arms of Portugal as pretender to the throne of that kingdom. The Royal Arms of Castile quartered with the Leonese ones were borne by the Castilian monarchs until the reign of the Catholic Monarchs. The quartering was remained as symbol associated with the Crown of Castile territory until the promulgation of the Nueva Planta decrees by Philip V in 1715.

Hispanic Monarchy and current uses

.svg.png.webp)

In 1475, Isabella of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon joined the arms of the Crowns of Castile and Aragon in a quarterly shield. It followed the method created by Fernando III and giving the arms of Castile pride of place again. A series of dynastic marriages[4] enabled the House of Habsburg to occupy the thrones of Castile, Aragon and Navarre, the arms of Castile have appeared in the arms of all Spanish monarchs and, since 1869 when was adopted, in all versions of the national coat of arms. As above, in all these cases giving the Castilian arms pride of place.

Leaving aside the Spanish local and provincial heraldry, where can be found numerous examples and being the most prominent the coat of arms of Toledo, the Castilian arms are among the elements of the coats of arms of the autonomous communities (regions) of Castile and León (which has adopted the quartering of Ferdinand III), La Rioja, Castile-La Mancha, Extremadura, Madrid, Murcia and within the bordure of the autonomous city of Melilla.

Outside the Iberian Peninsula, the castle of Castile is depicted in the arms granted to capitals of the Spanish Empire, as is the case of the capital of Ecuador San Francisco de Quito, with a triple-towered castle Argent and two eagles Sable on field Gules. It was granted to Quito by King Charles I (Charles V as Holy Roman Emperor), in 1541.[5]

Crest and supporters

The Royal Crest of Castile, also called Crest of the Castle and the Lion, was it that used the last monarchs of Castile and Spain until the 19th century. This crest consisted of a castle or fortress with nascent lion on top. These two figures are charges of the Royal arms of the former Crown of Castile. King John II (1406–1454) adopted this crest was, its use is documented in ten and twenty doblas coins, minted in the city of Seville. According to historian José María de Francisco Olmos in his study of the late medieval Castilian currency, the obverse of these coins are represented a shield with the Device of the Bend and the Castilian Royal Crest. In the same study, the author recalls that the Crest of the Castle and the Lion is also represented at an image of King John II, an equestrian portrait of the Armorial of the Golden Fleece, preserved in the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal (Paris).[6]

Faustino Menéndez Pidal de Navascués noted that, previously, the Castilian monarchs had used a crest, consisting of the figure of a nascent griffin Or. This crest, reproduced in the Armorial de Gelre (folio page 60v), was used by Henry II, John I and Henry III.[7] After the reign of the Catholic Monarchs, there is evidence of its usage by Philip I in some versions of his achievement adopted as King jure uxoris of Castile. There are two prominent examples in his seal[8] and the book of the Order of the Golden Fleece, illustrated by Simon Bening. The achievement of King Philip I was reproduced in this book due his status as sovereign and grand master of this order.[9]

The Spanish monarchs of the House of Habsburg also maintained the royal crest in their achievement. At the beginning of the 16th century the lion of the crest, crowned, began to hold a sword and a globus cruciger. Philip II and Philip III added two crowned helmets with nascent dragons, the crests of the Portuguese and Aragonese monarchs; besides, it gave the crest and arms of Castile pride of place (the central position). This achievement is placed above the bronze figures, portrait of the family of Philip II, by the Milanese sculptor Pompeo Leoni (1533-1608), son of Leone Leoni , that are located in the interior of the Basilica of El Escorial (Madrid).[10][11]

Because of Spanish monarchs gave the Castilian quarters pride of place in their arms, the Royal Crest of Castile remained as single crest at their armorial achievement. Both latest versions of the armorial achievement of Spain with the royal crest, adopted by Philip V and his son Charles III, showed the lion of the crest with a modern royal crown (with eight half arches) and a scroll charged with the battle cry Santiago!. The meaning of the phrase is to praise St. James the apostle, patron saint of Spain. At that time, it was usual to consider the Royal Crest of Castile as the crest of the whole of Spain, thus it was exposed by heraldists as José de Avilés e Iturbide, 1st Marquis of Avilés, in his book Ciencia heroyca. Since the 18th century, full royal armorial achievements were used occasionally and the crest of the Castle and lion practically fell into disuse[12][13] until its demise in 1975, when the Spanish monarchy was restored.[14]

In heraldry, supporters are figures or objects usually placed on either side of the shield and depicted holding it up, first appeared in English heraldry in the 15th century. Originally, they were not regarded as an integral part of arms, and were subject to frequent change. Lions were sporadically shown supporting the arms of the Castilian monarch and were introduced by John II.[15] The lions as supporters were displayed until the reign of Philip V[13] and, after 1868, in some ornate versions of the national arms of Spain.[16]

The arms of the Crown of Castile with the ancient royal crest

The arms of the Crown of Castile with the ancient royal crest The Castilian arms with the Crest of the Castle and the Lion. During the reign of John II the royal crest was represented over the Device of the Bend depicted on a shield

The Castilian arms with the Crest of the Castle and the Lion. During the reign of John II the royal crest was represented over the Device of the Bend depicted on a shield.svg.png.webp) Full armorial achievement of the Monarch of Spain since Charles III with the Crest of the Castle and the Lion

Full armorial achievement of the Monarch of Spain since Charles III with the Crest of the Castle and the Lion

Castilian flags

As it was quite usual during the Middle Ages many flags, banners and standards were not standardized. There has never been a Castilian royal standard or banner with a unique design. There were varied designs of the castle or colours of the fabric, depending on the artisan or prevailing fashion. They have their origin in the representation of the arms of the Castilian monarch on cloth to be used as flag and, by extension were emblem of the Kingdom and the Historic Region of Castile. The field Gules was represented in more or less dark reddish tones, although a more specific colour, crimson, has been used very frequently in Castile.

Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Castile

Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Castile.svg.png.webp) Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Castile

Royal Standard of the Kingdom of Castile

(Variant).svg.png.webp) Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

(14th century).svg.png.webp) Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

(15th century)-Variant.svg.png.webp) Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile. Square Shape

Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile. Square Shape

(15th century).svg.png.webp) Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

Royal Standard of the Crown of Castile

(ca.1500-1715)

A triple-towered castle on red or crimson fabric has shown in standards used by Castilian monarchs. The quartering of Ferdinand III was also displayed on his standard and it has served as the basis for current flags of autonomous communities of Castile and León and Castile-La Mancha. Further confusions led to apply the colour purple to a legendary «Castilian banner» (which neither preserved nor has never been documented), identifying the color purple as symbol of the Kingdom of Castile, something that influenced in the flag of the Second Spanish Republic and its lowest band. There are different hypotheses to explain the origin of the confusion. Fundamentally, the origin part of chromatic colour relationship among purple and red/crimson. Colour crimson was also widely used to represent the color purple, used in the ancient world as symbol of the sovereignty and authority of monarchs. One of the assumptions made is supported by the fact that with the passage of time many cloths, that originally were crimson, worn may become confused with other tones, as the purple.[17][18] These inaccuracies were the creation of a legend on the purple colour of the banner used during the Revolt of the Comuneros against King Charles I of Castile and Aragon (later Holy Roman Emperor Charles V), between 1520 and 1521.[19] Nowadays Castilian nationalism movement uses a purple flag charged with the triple-towered castle in the center and Castilian Leftist groups included the castle within a red star.

A Modern Interpretation. Colour Crimson

A Modern Interpretation. Colour Crimson

(Unofficial) Another Modern Interpretation. Colour Red

Another Modern Interpretation. Colour Red

(Unofficial).svg.png.webp) Flag used by Castilian Nationalists

Flag used by Castilian Nationalists

(Unofficial).svg.png.webp) Flag used by Castilian Leftist Groups

Flag used by Castilian Leftist Groups

(Unofficial)

See also

- Royal Bend of Castile, guidon of the monarch of the Crown of Castile

- Castile

- Old Castile and New Castile

- Crown of Castile

- Kingdom of Castile

- Castilianism

- Coat of arms of Castile and León

- Coat of arms of Spain

- Coat of arms of Portugal

- Royal Arms of England

- Flag of Castile and León

- Quartering (heraldry)

- Heraldry of León

- Spanish heraldry

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to |

- García de Cortázar, J.A.; Sesma Muñoz, J.A. (1998) La Edad Media: una síntesis interpretativa [The Middle Ages: an interpretive synthesis]. Madrid: Alianza Editorial. P. 681. ISBN 84-206-2894-8

- (in Spanish) Act 33/1981, 5 October (BOE Nro. 250, 19 October 1981). Coat of arms of Spain.

- Thomas Woodcock & John Martin Robinson, The Oxford Guide to Heraldry, Oxford University Press, New York (1988), p. 1.

- Paula Sutter Fichtner, "Dynastic Marriage in Sixteenth-Century Habsburg Diplomacy and Statecraft: An Interdisciplinary Approach," American Historical Review Vol. 81, No. 2 (April 1976), pp. 243-265 in JSTOR

- "Escudo de armas de Quito" [Coat of arms of Quito] (in Spanish). in-quito.com. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Francisco Olmos, José María de. "La moneda de la Castilla bajomedieval: medio de propaganda e instrumento económico" [The currency of Castile in the Late Middle Ages: means of propaganda and economic instrument] (PDF) (in Spanish). Complutense University of Madrid. pp. 325–327. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- Menéndez Pidal 1999, p. 89.

- Image of the seal of King Philip I of Castile: Posse, O. Die Siegel der deutschen Kaiser und Könige v. 3 (1493 - 1711) , 1912.

- Image of the achievement of King Philip I with the Royal Crest of Castile by Simon Bening.

- Menéndez Pidal 1999, p. 196.

- Image of the achievement with crests located in the Basilica of El Escorial.

- Avilés, José de Avilés, Marqués de. Ciencia heroyca, reducida a las leyes heráldicas del blasón, Madrid: J. Ibarra, 1780 (Reimp. Madrid: Bitácora, 1992). T. 2, p. 162-166. ISBN 84-465-0006-X.

- Castañeda y Alcover, Vicente. "Las armas reales de España" [The royal arms of Spain] (in Spanish). Heraldica hispanica.com. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- "Real Decreto 527/2014, de 20 de junio, por el que se crea el Guión y el Estandarte de Su Majestad el Rey Felipe VI y se modifica el Reglamento de Banderas y Estandartes, Guiones, Insignias y Distintivos, aprobado por Real Decreto 1511/1977, de 21 de enero" [Royal Decree 527/2014 setting up the Guidon and Standard of HM King Felipe VI and amends Standards, Guidons, Insignia and Emblems Regulation, adopted on Royal Decree 1511/1977] (PDF). BOE Spanish Official Journal (in Spanish). 20 June 2014. Retrieved 2018-08-29.

- Menéndez Pidal 1999, p. 86.

- "El escudo franquista que preside el túnel, todo un símbolo del abandono" [The Francoist coat of arms, that presides over the tunnel, a symbol of neglect]. www.heraldo.es (in Spanish). 5 August 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2018.

- O´Donnell, Hugo. La bandera [The flag]. P. 356. En Menéndez Pidal y Navascués, Faustino; O´Donnell, Hugo; Lolo, Begoña. Símbolos de España. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales, 1999. ISBN 84-259-1074-9

- Álvarez Abeilhé, Juan L. (2010). "La bandera de España. El origen militar de los símbolos de España." [The flag of Spain. Military origin of the symbols of Spain]. Revista de historia militar (in Spanish). Madrid: Ministerio de Defensa (Special issue): 71–72. ISSN 0482-5748.

- Sánchez, Francisco Javier (22 November 2015). "El falso color morado como de Castilla o de los comuneros" [The false purple as of Castile or Comuneros] (in Spanish). Castilla: Temática castellana. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

Sources

- Menéndez Pidal De Navascués, Faustino (1999) El escudo [The coat of arms]; Menéndez Pidal y Navascués, Faustino; O´Donnell, Hugo; Lolo, Begoña. Símbolos de España [Symbols of Spain]. Madrid: Centro de Estudios Políticos y Constitucionales. ISBN 84-259-1074-9.

- Menéndez-Pidal De Navascués, Faustino (2004) El Escudo de España [The coat of arms of Spain], Real Academia Matritense de Heráldica y Genealogía, Madrid. PP. 64–78. ISBN 84-88833-02-4

External links

- The standard of Castile (In Spanish)

- The coat of arms of Castile – Blog de heráldica (In Spanish)

.svg.png.webp)