Hess's law

Hess' law of constant heat summation, also known as Hess' law (or Hess's law), is a relationship in physical chemistry named after Germain Hess, a Switzerland-born Russian chemist and physician who published it in 1840. The law states that the total enthalpy change during the complete course of a chemical reaction is the same whether the reaction is made in one step or in several steps.[1][2]

Hess' law is now understood as an expression of the principle of conservation of energy, also expressed in the first law of thermodynamics, and the fact that the enthalpy of a chemical process is independent of the path taken from the initial to the final state (i.e. enthalpy is a state function). Reaction enthalpy changes can be determined by calorimetry for many reactions. The values are usually stated for processes with the same initial and final temperatures and pressures, although the conditions can vary during the reaction. Hess' law can be used to determine the overall energy required for a chemical reaction, when it can be divided into synthetic steps that are individually easier to characterize. This affords the compilation of standard enthalpies of formation, that may be used as a basis to design complex syntheses.

Theory

The Hess' law states that the change of enthalpy in a chemical reaction (i.e. the heat of reaction at constant pressure) is independent of the pathway between the initial and final states.

In other words, if a chemical change takes place by several different routes, the overall enthalpy change is the same, regardless of the route by which the chemical change occurs (provided the initial and final condition are the same).

Hess' law allows the enthalpy change (ΔH) for a reaction to be calculated even when it cannot be measured directly. This is accomplished by performing basic algebraic operations based on the chemical equations of reactions using previously determined values for the enthalpies of formation.

Addition of chemical equations leads to a net or overall equation. If enthalpy change is known for each equation, the result will be the enthalpy change for the net equation. If the net enthalpy change is negative (ΔHnet < 0), the reaction is exothermic and is more likely to be spontaneous; positive ΔH values correspond to endothermic reactions. Entropy also plays an important role in determining spontaneity, as some reactions with a positive enthalpy change are nevertheless spontaneous.

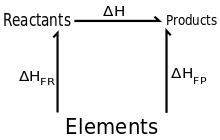

Hess' law states that enthalpy changes are additive. Thus the ΔH for a single reaction

where is an enthalpy of formation, and the o superscript indicates standard state values. This may be considered as the sum of two (real or fictitious) reactions:

- Reactants → Elements

and Elements → Products

Examples

1) a) Cgraphite+O2 → CO2 (g) ;(ΔH = –393.5 kJ/mol) (direct step)

- b) Cgraphite+1/2 O2 → CO (g) ; (ΔH = –110.5 kJ/mol)

- c) CO (g)+1/2 O2 → CO2 (g); (ΔH = –283.02 kJ/mol)

Reaction a) is the sum of reactions b) and c), for which the total ΔH = –393.5 kJ/mol which is equal to ΔH in a).

The difference in the value of ΔH is 0.02 kJ/mol which is due to measurement errors .

2) Given:

- B2O3 (s) + 3H2O (g) → 3O2 (g) + B2H6 (g) (ΔH = 2035 kJ/mol)

- H2O (l) → H2O (g) (ΔH = 44 kJ/mol)

- H2 (g) + (1/2)O2 (g) → H2O (l) (ΔH = –286 kJ/mol)

- 2B (s) + 3H2 (g) → B2H6 (g) (ΔH = 36 kJ/mol)

Find the ΔHf of:

- 2B (s) + (3/2) O2 (g) → B2O3 (s)

After multiplying the equations (and their enthalpy changes) by appropriate factors and reversing the direction when necessary, the result is:

- B2H6 (g) + 3O2 (g) → B2O3 (s) + 3H2O (g) (ΔH = 2035 x (–1) = –2035 kJ/mol)

- 3H2O (g) → 3H2O (l) (ΔH = 44 x (–3) = –132 kJ/mol)

- 3H2O (l) → 3H2 (g) + (3/2) O2 (g) (ΔH = –286 x (–3) = +858 kJ/mol)

- 2B (s) + 3H2 (g) → B2H6 (g) (ΔH = 36 kJ/mol = 36 kJ/mol)

Adding these equations and canceling out the common terms on both sides, we obtain

- 2B (s) + (3/2) O2 (g) → B2O3 (s) (ΔH = –1273 kJ/mol)

Extension to free energy and entropy

The concepts of Hess' law can be expanded to include changes in entropy and in Gibbs free energy, which are also state functions. The Bordwell thermodynamic cycle is an example of such an extension which takes advantage of easily measured equilibria and redox potentials to determine experimentally inaccessible Gibbs free energy values. Combining ΔGo values from Bordwell thermodynamic cycles and ΔHo values found with Hess' law can be helpful in determining entropy values which are not measured directly, and therefore must be calculated through alternative paths.

For the free energy:

For entropy, the situation is a little different. Because entropy can be measured as an absolute value, not relative to those of the elements in their reference states (as with ΔHo and ΔGo), there is no need to use the entropy of formation; one simply uses the absolute entropies for products and reactants:

Applications

Hess' Law of Constant Heat Summation is useful in the determination of enthalpies of the following:[1]

- Heats of formation of unstable intermediates like CO(g) and NO(g).

- Heat changes in phase transitions and allotropic transitions.

- Lattice energies of ionic substances by constructing Born-Haber cycles if the electron affinity to form the anion is known, or

- Electron affinities using a Born-Haber cycle with a theoretical lattice energy

See also

References

- Mannam Krishnamurthy; Subba Rao Naidu (2012). "7". In Lokeswara Gupta (ed.). Chemistry for ISEET - Volume 1, Part A (2012 ed.). Hyderabad, India: Varsity Education Management Limited. p. 244.

- "Hess' Law - Conservation of Energy". University of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 9 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2014.

- Chakrabarty, D.K. (2001). An Introduction to Physical Chemistry. Mumbai: Alpha Science. pp. 34–37. ISBN 1-84265-059-9.

Further reading

- Leicester, Henry M. (1951). "Germain Henri Hess and the Foundations of Thermochemistry". The Journal of Chemical Education. 28 (11): 581–583. Bibcode:1951JChEd..28..581L. doi:10.1021/ed028p581.

External links

- Hess' paper (1840) on which his law is based (at ChemTeam site)

- a Hess’ Law experiment